The Cathar Crucifix: New Evidence of the Shroud’S Missing History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Physical Death of Jesus Christ

On the Physical Death of Jesus Christ William D. Edwards, MD; Wesley J. Gabel, MDiv; Floyd E. Hosmer, MS, AMI Jesus of Nazareth underwent Jewish and Roman trials, was flogged, Talmud, and by the Jewish historian and was sentenced to death by crucifixion. The scourging produced deep Flavius Josephus, although the au¬ stripelike lacerations and appreciable blood loss, and it probably set the thenticity of portions of the latter is stage for hypovolemic shock, as evidenced by the fact that Jesus was too problematic.26 weakened to carry the crossbar (patibulum) to Golgotha. At the site of The Shroud of Turin is considered crucifixion, his wrists were nailed to the patibulum and, after the patibulum by many to represent the actual buri¬ was lifted onto the upright post (stipes), his feet were nailed to the stipes. al cloth of Jesus,22 and several publi¬ The major pathophysiologic effect of crucifixion was an interference with cations concerning the medical as¬ normal respirations. Accordingly, death resulted primarily from hypovolemic pects of his death draw conclusions shock and exhaustion asphyxia. Jesus' death was ensured by the thrust of a from this assumption."' The Shroud soldier's spear into his side. Modern medical interpretation of the historical of Turin and recent archaeological evidence indicates that Jesus was dead when taken down from the cross. findings provide valuable information (JAMA 1986;255:1455-1463) concerning Roman crucifixion prac¬ tices.2224 The interpretations of mod¬ ern writers, based on a knowledge of THE LIFE and teachings of Jesus of credibility of any discussion of Jesus' science and medicine not available in Nazareth have formed the basis for a death will be determined primarily by the first century, may offer addition¬ major world religion (Christianity), the credibility of one's sources. -

Sources of Donatello's Pulpits in San Lorenzo Revival and Freedom of Choice in the Early Renaissance*

! " #$ % ! &'()*+',)+"- )'+./.#')+.012 3 3 %! ! 34http://www.jstor.org/stable/3047811 ! +565.67552+*+5 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org THE SOURCES OF DONATELLO'S PULPITS IN SAN LORENZO REVIVAL AND FREEDOM OF CHOICE IN THE EARLY RENAISSANCE* IRVING LAVIN HE bronze pulpits executed by Donatello for the church of San Lorenzo in Florence T confront the investigator with something of a paradox.1 They stand today on either side of Brunelleschi's nave in the last bay toward the crossing.• The one on the left side (facing the altar, see text fig.) contains six scenes of Christ's earthly Passion, from the Agony in the Garden through the Entombment (Fig. -

1 Santo Spirito in Florence: Brunelleschi, the Opera, the Quartiere and the Cantiere Submitted by Rocky Ruggiero to the Universi

Santo Spirito in Florence: Brunelleschi, the Opera, the Quartiere and the Cantiere Submitted by Rocky Ruggiero to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History and Visual Culture In March 2017. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature)…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Abstract The church of Santo Spirito in Florence is universally accepted as one of the architectural works of Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446). It is nevertheless surprising that contrary to such buildings as San Lorenzo or the Old Sacristy, the church has received relatively little scholarly attention. Most scholarship continues to rely upon the testimony of Brunelleschi’s earliest biographer, Antonio di Tuccio Manetti, to establish an administrative and artistic initiation date for the project in the middle of Brunelleschi’s career, around 1428. Through an exhaustive analysis of the biographer’s account, and subsequent comparison to the extant documentary evidence from the period, I have been able to establish that construction actually began at a considerably later date, around 1440. It is specifically during the two and half decades after Brunelleschi’s death in 1446 that very little is known about the proceedings of the project. A largely unpublished archival source which records the machinations of the Opera (works committee) of Santo Spirito from 1446-1461, sheds considerable light on the progress of construction during this period, as well as on the role of the Opera in the realization of the church. -

{DOWNLOAD} Cross

CROSS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Patterson | 464 pages | 29 Apr 2010 | Headline Publishing Group | 9780755349401 | English | London, United Kingdom Cross Pens for Discount & Sales | Last Chance to Buy | Cross The Christian cross , seen as a representation of the instrument of the crucifixion of Jesus , is the best-known symbol of Christianity. For a few centuries the emblem of Christ was a headless T-shaped Tau cross rather than a Latin cross. Elworthy considered this to originate from Pagan Druids who made Tau crosses of oak trees stripped of their branches, with two large limbs fastened at the top to represent a man's arm; this was Thau, or god. John Pearson, Bishop of Chester c. In which there was not only a straight and erected piece of Wood fixed in the Earth, but also a transverse Beam fastened unto that towards the top thereof". There are few extant examples of the cross in 2nd century Christian iconography. It has been argued that Christians were reluctant to use it as it depicts a purposely painful and gruesome method of public execution. The oldest extant depiction of the execution of Jesus in any medium seems to be the second-century or early third-century relief on a jasper gemstone meant for use as an amulet, which is now in the British Museum in London. It portrays a naked bearded man whose arms are tied at the wrists by short strips to the transom of a T-shaped cross. An inscription in Greek on the obverse contains an invocation of the redeeming crucified Christ. -

Michelangelo Buonarroti Artstart – 3 Dr

Michelangelo Buonarroti ArtStart – 3 Dr. Hyacinth Paul https://www.hyacinthpaulart.com/ The genius of Michelangelo • Renaissance era painter, sculptor, poet & architect • Best documented artist of the 16th century • He learned to work with marble, a chisel & a hammer as a young child in the stone quarry’s of his father • Born 6th March, 1475 in Caprese, Florence, Italy • Spent time in Florence, Bologna & Rome • Died in Rome 18th Feb 1564, Age 88 Painting education • Did not like school • 1488, age 13 he apprenticed for Domenico Ghirlandaio • 1490-92 attended humanist academy • Worked for Bertoldo di Giovanni Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Sistine Chapel Ceiling – (1508-12) Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo Doni Tondo (Holy Family) (1506) – Uffizi, Florence Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Creation of Adam (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Last Judgement - (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo Ignudo (1509) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Drunkenness of Noah - (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Deluge - (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The First day of creation - - (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Prophet Jeremiah - (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The last Judgement - (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Crucifixion of St. Peter - (1546-50) – Vatican, Rome Only known Self Portrait Famous paintings of Michelangelo -

Crucifixion in Antiquity: an Inquiry Into the Background and Significance of the New Testament Terminology of Crucifixion

GUNNAR SAMUELSSON Crucifixion in Antiquity Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 2. Reihe 310 Mohr Siebeck Gunnar Samuelsson questions the textual basis for our knowledge about the death of Jesus. As a matter of fact, the New Testament texts offer only a brief description of the punishment that has influenced a whole world. ISBN 978-3-16-150694-9 Mohr Siebeck Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament · 2. Reihe Herausgeber / Editor Jörg Frey (Zürich) Mitherausgeber / Associate Editors Friedrich Avemarie (Marburg) Markus Bockmuehl (Oxford) James A. Kelhoffer (Uppsala) Hans-Josef Klauck (Chicago, IL) 310 Gunnar Samuelsson Crucifixion in Antiquity An Inquiry into the Background and Significance of the New Testament Terminology of Crucifixion Mohr Siebeck GUNNAR SAMUELSSON, born 1966; 1992 Pastor and Missionary Degree; 1997 B.A. and M.Th. at the University of Gothenburg; 2000 Μ. Α.; 2010 ThD; Senior Lecturer in New Testament Studies at the Department of Literature, History of Ideas and Religion, University of Gothenburg. ISBN 978-3-16-150694-9 ISSN 0340-9570 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament, 2. Reihe) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbiblio graphie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. ©2011 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed by Laupp & Göbel in Nehren on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Nadele in Nehren. -

1. Crucifixion

1. Crucifixion By: Paul T. Fanning, Tyler, Texas1 “We preach Christ, and Christ crucified – to the Jews a stumbling block, and to the Gentiles foolishness.” 1 Corinthians 1:23. While we are studying this topic,2 please ponder one question in the back of your mind: ‘Why did Jesus have to be crucified?’ After all, couldn’t the “plan” have provided for the Messiah pricking His finger with a pin and allowing just one drop of His sacred blood to fall to earth before He died peacefully in His sleep and then risen? After all, He is the Alpha and the Omega, the eternal God of the Universe, and infinitely both holy and good. Wouldn’t just the inconvenience of having to adopt human flesh and nature and spilling just one drop of His sacred blood have been sufficient to cleanse the whole planet of sin? Why did Jesus become a spectacle and give it all? We know He didn’t want to do it.3 1 Paul T. Fanning earned B.A. and J.D. degrees from The University Of Texas At Austin in 1968 and 1972, respectively. He was then encouraged by Dr. David O. Dykes, Pastor of Green Acres Baptist Church, Tyler, Texas, who convinced him that he actually could do “this.” Thereafter, he was privileged to study under two of the outstanding Bible scholars of our time, Thomas S. McCall, Th.D. (September 1, 1936 – ), and Mal Couch, Ph.D., Th.D., (July 12, 1938 – February 12, 2013) who participated in his ordination at Clifton Bible Church, Clifton, Texas, on March 8, 2011. -

Michelangelo Buonarotti

MICHELANGELO BUONAROTTI Portrait of Michelangelo by Daniele da Volterra COMPILED BY HOWIE BAUM Portrait of Michelangelo at the time when he was painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. by Marcello Venusti Hi, my name is Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, but you can call me Michelangelo for short. MICHAELANGO’S BIRTH AND YOUTH Michelangelo was born to Leonardo di Buonarrota and Francesca di Neri del Miniato di Siena, a middle- class family of bankers in the small village of Caprese, in Tuscany, Italy. He was the 2nd of five brothers. For several generations, his Father’s family had been small-scale bankers in Florence, Italy but the bank failed, and his father, Ludovico di Leonardo Buonarroti Simoni, briefly took a government post in Caprese. Michelangelo was born in this beautiful stone home, in March 6,1475 (546 years ago) and it is now a museum about him. Once Michelangelo became famous because of his beautiful sculptures, paintings, and poetry, the town of Caprese was named Caprese Michelangelo, which it is still named today. HIS GROWING UP YEARS BETWEEN 6 AND 13 His mother's unfortunate and prolonged illness forced his father to place his son in the care of his nanny. The nanny's husband was a stonecutter, working in his own father's marble quarry. In 1481, when Michelangelo was six years old, his mother died yet he continued to live with the pair until he was 13 years old. As a child, he was always surrounded by chisels and stone. He joked that this was why he loved to sculpt in marble. -

Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist, Saint Peter, and Two Angels C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Tuscan 13th Century Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist, Saint Peter, and Two Angels c. 1290 tempera on panel painted surface (original panel including painted frame): 34.3 × 24.7 cm (13 1/2 × 9 3/4 in.) overall (including added wooden strips): 36 × 26 cm (14 3/16 × 10 1/4 in.) Inscription: on the scroll held by Saint John the Baptist: E[C]CE / AGNU[S] / DEI:[ECCE] / [Q]UI [TOLLIT PECCATUM MUNDI] (from John 1:29) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1952.5.60 ENTRY The enthroned Madonna supports her son, seated on her left knee, with both hands. The child, in a frontal position, blesses with his right hand, holding a roll of parchment in his left. The composition is a variant of the type of the Hodegetria Virgin; in the present case, she does not point towards her son, as in the Byzantine prototype, but instead presents him to the spectator. [1] Her affectionate maternal pose is thus given precedence over her more ritual and impersonal role. But Mary’s pose perhaps has another sense: she seems to be rearranging her son’s small legs to conform them to the cross-legged position considered suitable for judges and sovereigns in the Middle Ages. [2] The panel is painted in a rapid, even cursory manner. The artist omits the form of the throne’s backrest, which remains hidden by the cloth of honor, supported by angels and decorated with bold motifs of popular taste (an interlocking pattern of quatrefoils and octagons). -

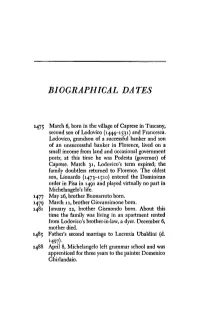

Biographical Dates

BIOGRAPHICAL DATES 1475 March 6, born in the village of Caprese in Tuscany, second son of Lodovico (1444-1531) and Francesca. Lodovico, grandson of a successful banker and son of an unsuccessful banker in Florence, lived on a small income from land and occasional government posts; at this time he was Podesta (governor) of Caprese. March 31, Lodovico's term expired; the family doubtless returned to Florence. The oldest son, Lionardo (1473-1510) entered the Dominican order in Pisa in 1491 and played virtually no part in Michelangelo's life. 1477 May 26, brother Buonarroto bom. 1479 March 11, brother Giovansimone born. 1481 January 22, brother Gismondo bom. About this time the family was living in an apartment rented from Lodovico's brother-in-law, a dyer. December 6, mother died. 1485 Father's second marriage to Lucrezia Ubaldini (d. M97)- 1488 April 8, Michelangelo left grammar school and was apprenticed for three years to the painter Domenico Ghirlandaio. MICHELANGELO [1] 1489 Left Ghirlandaio and studied sculpture in the gar- den of Lorenzo de' Medici the Magnificent. 1492 Lorenzo the Magnificent died, succeeded by his old- est son Piero. 1494 Rising against Piero de' Medici, who fled (d. 1503). Republic re-established under Savonarola. October, Michelangelo fled and after a brief stay in Venice went to Bologna. 1495 In Bologna, carved three small statues which brought to completion the tomb of St. Dominic. Returned to Florence, carved the Cupid, sold to Baldassare del Milanese, a dealer. 1496 June, went to Rome. Carved the Bacchus for the banker Jacopo Galli. 1497 November, went to Carrara to obtain marble. -

The Craftsman Revealed: Adriaen De Vries, Sculptor

This page intentionally left blank The Craftsman Revealed Adriaen de Vries Sculptor in Bronze This page intentionally left blank The Craftsman Revealed Adriaen de Vries Sculptor in Bronze Jane Bassett with contributions by Peggy Fogelman, David A. Scott, and Ronald C. Schmidtling II THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE Los ANGELES The Getty Conservation Institute Timothy P. Whalen, Director Jeanne Marie Teutónico, Associate Director, Programs The Getty Conservation Institute works internationally to advance conservation practice in the visual arts—broadly interpreted to include objects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute serves the conservation community through scientific research, education and training, model field projects, and the dissemination of the results of both its own work and the work of others in the field. In all its endeavors, the GCI focuses on the creation and delivery of knowledge that will benefit the professionals and organizations responsible for the conservation of the world's cultural heritage. Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu © 2008 J. Paul Getty Trust Gregory M. Britton, Publisher Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief Tevvy Ball, Editor Sheila Berg, Copy Editor Pamela Heath, Production Coordinator Hespenheide Design, Designer Printed and bound in China through Asia Pacific Offset, Inc. FRONT COVER: Radiograph of Juggling Man, by Adriaen de Vries. Bronze. Cast in Prague, 1610–1615. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Inv. no. 90.SB.44. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bassett, Jane. The craftsman revealed : Adriaen de Vries, sculptor in bronze / Jane Bassett ; with contributions by Peggy Fogelman, David A. Scott, and Ronald C. -

Download Brochure

witness the lives of the saints You’re invited on a pilgrimage to the saints & shrines of italy May 16-26, 2022 Basilica of St. Clare, which holds the famous San Damiano Crucifix that spoke to St. Francis, and where the golden locks of St. Clare’s a truly catholic pilgrimage hair and St. Francis’ poor patched tunic are kept. This afternoon we will travel up Mt. Subasio to L’Eremo delle Carceri (the Carceri Hermitage), St. Francis’ favorite retreat center, where he could Tekton Ministries has been leading Catholic pilgrimages for more than remain in seclusion and prayer. Enjoy some personal prayer time in 20 years. Working closely with your priest to create thoughtfully planned this peaceful location before enjoying a dinner out together at a local itineraries, we help make the Catholic faith more tangible to your daily winery. (B/D, Mass) life by taking you to the heart of our Mother Church today. Although we visit more than 50 sites in this holy and historic region, daily Mass and l Day 4 - Thursday, May 19 time for prayerful reflection are important parts of each day’s experience. Assisi / Day trip to Siena: Eucharistic Miracle, St. Dominic’s, Piazza del Campo We use only experienced Christian or Catholic guides, so you receive The home of St. Catherine of Siena beckons as we venerate the great Eucharistic Miracle of Siena at the Basilica of St. Francis on our day truthful explanations of scripture and the places we encounter. When trip from Assisi. Thieves stole a container of consecrated Hosts, which the disciple Philip asked the Eunuch (who was reading Isaiah) if he were later found in the church’s offertory box.