Arbeitspflicht in Postwar Vienna: Punishing Nazis Vs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buchanan on Bischof and Petschar, 'The Marshall Plan: Saving Europe, Rebuilding Austria'

H-Diplo Buchanan on Bischof and Petschar, 'The Marshall Plan: Saving Europe, Rebuilding Austria' Review published on Saturday, April 21, 2018 Günter Bischof, Hans Petschar. The Marshall Plan: Saving Europe, Rebuilding Austria. New Orleans: University of New Orleans Publishing, 2017. 336 pp. $49.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-60801-147-6. Reviewed by Andrew N. Buchanan (University of Vermont)Published on H-Diplo (April, 2018) Commissioned by Seth Offenbach (Bronx Community College, The City University of New York) Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=50939 The bibliographic details of this book should probably include its size (9.5” by 12”) and its weight (five pounds). This is a physically impressive book, and its sheer size, beautiful design, and lavish illustration suggest a work intended for display on coffee tables rather than use in academic studies. Yet the authors are both senior scholars of Austrian history and of the Marshall Plan in particular. Günter Bischof is the Marshall Plan Professor of History at the University of New Orleans and Hans Petschar is a historian and librarian at the Austrian National Library and the holder of the 2016-17 visiting Marshall Plan Chair at the University of New Orleans. Their credentials suggest that the authors have something more than a coffee table book in mind, and as it weaves its way through the pages of photographs their text offers a serious scholarly appreciation of the working of the Marshall Plan in Austria. Austria found itself in an ambiguous—not to say dangerous—position at the end of World War II. -

Danube River Cruise Flyer-KCTS9-MAURO V2.Indd

AlkiAlki ToursTours DanubeDanube RiverRiver CruiseCruise Join and Mauro & SAVE $800 Connie Golmarvi from Assaggio per couple Ristorante on an Exclusive Cruise aboard the Amadeus Queen October 15-26, 2018 3 Nights Prague & 7 Nights River Cruise from Passau to Budapest • Vienna • Linz • Melk • and More! PRAGUE CZECH REPUBLIC SLOVAKIA GERMANY Cruise Route Emmersdorf Passau Bratislava Motorcoach Route Linz Vienna Budapest Extension MUNICH Melk AUSTRIA HUNGARY 206.935.6848 • www.alkitours.com 6417-A Fauntleroy Way SW • Seattle, WA 98136 TOUR DATES: October *15-26, 2018 12 Days LAND ONLY PRICE: As low as $4249 per person/do if you book early! Sail right into the pages of a storybook along the legendary Danube, *Tour dates include a travel day to Prague. Call for special, through pages gilded with history, and past the turrets and towers of castles optional Oct 15th airfare pricing. steeped in legend. You’ll meander along the fabled “Blue Danube” to grand cities like Vienna and Budapest where kings and queens once waltzed, and to gingerbread towns that evoke tales of Hansel and Gretel and the Brothers Grimm. If you listen closely, you might hear the haunting melody of the Lorelei siren herself as you cruise past her infamous river cliff post! PEAK SEASON, Five-Star Escorted During this 12-day journey, encounter the grand cities and quaint villages along European Cruise & Tour the celebrated Danube River. Explore both sides of Hungary’s capital–traditional Vacation Includes: “Buda” and the more cosmopolitan “Pest”–and from Fishermen’s Bastion, see how the river divides this fascinating city. Experience Vienna’s imperial architec- • Welcome dinner ture and gracious culture, and tour riverside towns in Austria’s Wachau Valley. -

The Vienna Children and Youth Strategy 2020 – 2025 Publishing Details Editorial

The Vienna Children and Youth Strategy 2020 – 2025 Publishing Details Editorial Owner and publisher: In 2019, the City of Vienna introduced in society. Thus, their feedback was Vienna City Administration the Werkstadt Junges Wien project, a taken very seriously and provided the unique large-scale participation pro- basis for the definition of nine goals Project coordinators: cess to develop a strategy for children under the Children and Youth Stra- Bettina Schwarzmayr and Alexandra Beweis and young people with the aim of tegy. Now, Vienna is for the first time Management team of the Werkstadt Junges Wien project at the Municipal Department for Education and Youth giving more room to the requirements bundling efforts from all policy areas, in cooperation with wienXtra, a young city programme promoting children, young people and families of Vienna’s young residents. The departments and enterprises of the “assignment” given to the children city and is aligning them behind the Contents: and young people participating in shared vision of making the City of The contents were drafted on the basis of the wishes, ideas and concerns of more than 22,500 children and young the project was to perform a “service Vienna a better place for all children people in consultation with staff of the Vienna City Administration, its associated organisations and enterprises check” on the City of Vienna: What and young people who live in the city. and other experts as members of the theme management groups in the period from April 2019 to December 2019; is working well? What is not working responsible for the content: Karl Ceplak, Head of Youth Department of the Province of Vienna well? Which improvements do they The following strategic plan presents suggest? The young participants were the results of the Werkstadt Junges Design and layout: entirely free to choose the issues they Wien project and outlines the goals Die Mühle - Visual Studio wanted to address. -

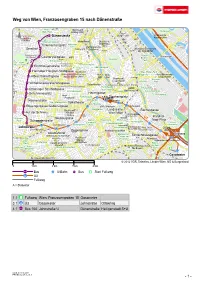

Footpath Description

Weg von Wien, Franzosengraben 15 nach Dänenstraße N Hugo- Bezirksamt Wolf- Park Donaupark Döbling (XIX.) Lorenz- Ignaz- Semmelweis- BUS Dänenstraße Böhler- UKH Feuerwache Kaisermühlen Frauenklinik Fin.- BFI Fundamt BUS Türkenschanzpark Verkehrsamt Bezirksamt amt Brigittenau Türkenschanzplatz Währinger Lagerwiese Park Rettungswache (XX.) Gersthof BUS Finanzamt Brigittenau Pensionsversicherung Brigittenau der Angestellten Orthopädisches Rudolf- BUS Donauinsel Kh. Gersthof Czartoryskigasse WIFI Bednar- Währing Augarten Schubertpark Park Dr.- Josef- 10A Resch- Platz Evangelisches AlsergrundLichtensteinpark BUS Richthausenstraße Krankenhaus A.- Carlson- Wettsteinpark Anl. BUS Hernalser Hauptstr./Wattgasse Bezirksamt Max-Winter-Park Allgemeines Krankenhaus Verk.- Verm.- Venediger Au Hauptfeuerwache BUS Albrechtskreithgasse der Stadt Wien (AKH) Amt Amt Leopoldstadt W.- Leopoldstadt Hernals Bezirksamt Kössner- Leopoldstadt Volksprater Park BUS Wilhelminenstraße/Wattgasse (II.) Polizeidirektion Krankenhaus d. Barmherz. Brüder Confraternität-Privatklinik Josefstadt Rudolfsplatz DDSG Zirkuswiese BUS Ottakringer Str./Wattgasse Pass-Platz Ottakring Schönbornpark Rechnungshof Konstantinhügel BUS Schuhmeierplatz Herrengasse Josefstadt Arenawiese BUS Finanzamt Rathauspark U Stephansplatz Hasnerstraße Volksgarten WienU Finanzamt Jos.-Strauss-Park Volkstheater Heldenplatz U A BUS Possingergasse/Gablenzgasse U B.M.f. Finanzen U Arbeitsamt BezirksamtNeubau Burggarten Landstraße- Rochusgasse BUS Auf der Schmelz Mariahilf Wien Mitte / Neubau BezirksamtLandstraßeU -

M1928 1945–1950

M1928 RECORDS OF THE GERMAN EXTERNAL ASSETS BRANCH OF THE U.S. ALLIED COMMISSION FOR AUSTRIA (USACA) SECTION, 1945–1950 Matthew Olsen prepared the Introduction and arranged these records for microfilming. National Archives and Records Administration Washington, DC 2003 INTRODUCTION On the 132 rolls of this microfilm publication, M1928, are reproduced reports on businesses with German affiliations and information on the organization and operations of the German External Assets Branch of the United States Element, Allied Commission for Austria (USACA) Section, 1945–1950. These records are part of the Records of United States Occupation Headquarters, World War II, Record Group (RG) 260. Background The U.S. Allied Commission for Austria (USACA) Section was responsible for civil affairs and military government administration in the American section (U.S. Zone) of occupied Austria, including the U.S. sector of Vienna. USACA Section constituted the U.S. Element of the Allied Commission for Austria. The four-power occupation administration was established by a U.S., British, French, and Soviet agreement signed July 4, 1945. It was organized concurrently with the establishment of Headquarters, United States Forces Austria (HQ USFA) on July 5, 1945, as a component of the U.S. Forces, European Theater (USFET). The single position of USFA Commanding General and U.S. High Commissioner for Austria was held by Gen. Mark Clark from July 5, 1945, to May 16, 1947, and by Lt. Gen. Geoffrey Keyes from May 17, 1947, to September 19, 1950. USACA Section was abolished following transfer of the U.S. occupation government from military to civilian authority. -

Leistbaren Wohnraum Schaffen – Stadt Weiter Bauen

Stadtpunkte Nr 25 Ernst Gruber, Raimund Gutmann, Margarete Huber, Lukas Oberhuemer (wohnbund:consult) LEISTBAREN WOHNRAUM SCHAFFEN – STADT WEITER BAUEN Potenziale der Nachverdichtung in einer wachsenden Stadt: Herausforderungen und Bausteine einer sozialverträglichen Umsetzung Jänner 2018 AK STADTPUNKTE 25 ■ Alle aktuellen AK Publikationen stehen zum Download für Sie bereit: wien.arbeiterkammer.at/service/publikationen Der direkte Weg zu unseren Publikationen: ■ E-Mail: [email protected] ■ Bestelltelefon: +43-1-50165 13047 Bei Verwendung von Textteilen wird um Quellenangabe und um Zusendung eines Belegexemplares an die Abteilung Kommunalpolitik der AK Wien ersucht. Impressum Medieninhaber: Kammer für Arbeiter und Angestellte für Wien, Prinz-Eugen-Straße 20–22, 1040 Wien Offenlegung gem. § 25 MedienG: siehe wien.arbeiterkammer.at/impressum Zulassungsnummer: AK Wien 02Z34648 M ISBN: 978-3-7063-0708-6 AuftraggeberInnen: AK Wien, Kommunalpolitik Fachliche Betreuung: Christian Pichler und Judith Wittrich Autoren: Margarete Huber, Ernst Gruber, Raimund Gutmann, Lukas Oberhuemer (wohnbund:consult) Grafik Umschlag und Druck: AK Wien Verlags- und Herstellungsort: Wien © 2018 bei AK Wien Stand Jänner 2018 Im Auftrag der Kammer für Arbeiter und Angestellte für Wien Ernst Gruber, Raimund Gutmann, Margarete Huber, Lukas Oberhuemer (wohnbund:consult) LEISTBAREN WOHNRAUM SCHAFFEN – STADT WEITER BAUEN Potenziale der Nachverdichtung in einer wachsenden Stadt: Herausforderungen und Bausteine einer sozialverträglichen Umsetzung Jänner 2018 VORWORT In einer -

Notes of Michael J. Zeps, SJ

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History Department 1-1-2011 Documents of Baudirektion Wien 1919-1941: Notes of Michael J. Zeps, S.J. Michael J. Zeps S.J. Marquette University, [email protected] Preface While doing research in Vienna for my dissertation on relations between Church and State in Austria between the wars I became intrigued by the outward appearance of the public housing projects put up by Red Vienna at the same time. They seemed to have a martial cast to them not at all restricted to the famous Karl-Marx-Hof so, against advice that I would find nothing, I decided to see what could be found in the archives of the Stadtbauamt to tie the architecture of the program to the civil war of 1934 when the structures became the principal focus of conflict. I found no direct tie anywhere in the documents but uncovered some circumstantial evidence that might be explored in the future. One reason for publishing these notes is to save researchers from the same dead end I ran into. This is not to say no evidence was ever present because there are many missing documents in the sequence which might turn up in the future—there is more than one complaint to be found about staff members taking documents and not returning them—and the socialists who controlled the records had an interest in denying any connection both before and after the civil war. Certain kinds of records are simply not there including assessments of personnel which are in the files of the Magistratsdirektion not accessible to the public and minutes of most meetings within the various Magistrats Abteilungen connected with the program. -

The Jewish Middle Class in Vienna in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries

The Jewish Middle Class in Vienna in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries Erika Weinzierl Emeritus Professor of History University of Vienna Working Paper 01-1 October 2003 ©2003 by the Center for Austrian Studies (CAS). Permission to reproduce must generally be obtained from CAS. Copying is permitted in accordance with the fair use guidelines of the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976. CAS permits the following additional educational uses without permission or payment of fees: academic libraries may place copies of CAS Working Papers on reserve (in multiple photocopied or electronically retrievable form) for students enrolled in specific courses; teachers may reproduce or have reproduced multiple copies (in photocopied or electronic form) for students in their courses. Those wishing to reproduce CAS Working Papers for any other purpose (general distribution, advertising or promotion, creating new collective works, resale, etc.) must obtain permission from the Center for Austrian Studies, University of Minnesota, 314 Social Sciences Building, 267 19th Avenue S., Minneapolis MN 55455. Tel: 612-624-9811; fax: 612-626-9004; e-mail: [email protected] 1 Introduction: The Rise of the Viennese Jewish Middle Class The rapid burgeoning and advancement of the Jewish middle class in Vienna commenced with the achievement of fully equal civil and legal rights in the Fundamental Laws of December 1867 and the inter-confessional Settlement (Ausgleich) of 1868. It was the victory of liberalism and the constitutional state, a victory which had immediate and phenomenal demographic and social consequences. In 1857, Vienna had a total population of 287,824, of which 6,217 (2.16 per cent) were Jews. -

VIENNA UNIVERSITY of TECHNOLOGY INTERNATIONAL OFFICE Gusshausstrasse 28 / 1St Floor, A-1040 Wien

VIENNA UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY INTERNATIONAL OFFICE Gusshausstrasse 28 / 1st floor, A-1040 Wien Contact: Tel: +43 (0)1 58801 - 41550 / 41552 Fax: +43 (0)1 58801 - 41599 Email: [email protected] ANKUNFT http://www.tuwien.ac.at/international Opening hours: Monday, Thursday: 9:30 a.m. – 11:30 a.m., 1:30 p.m. – 4:30 p.m. Wednesday: 9:30 a.m. – 11:30 a.m. How to reach us: Metro: U1 (Station Taubstummengasse) U2 (Station Karlsplatz) U4 (Station Karlsplatz) Tram: Line 62 (Station Paulanergasse) Line 65 (Station Paulanergasse) Line 71 (Station Schwarzenbergplatz) Welcome Guide TU Wien │ 1 Published by: International Office of Vienna University of Technology Gusshausstrasse 28 A-1040 Wien © 2014 Print financed by funds of the European Union 2 │ Welcome Guide TU Wien CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT TU WIEN .............................................. 5 1 History of Vienna University of Technology ......................................... 5 2 Structure of Vienna University of Technology ...................................... 6 3 Fields of Study ..................................................................................... 7 4 The Austrian National Union of Students ........................................... 11 PLANNING IN YOUR HOME COUNTRY..................................................... 13 1 Applying for Studies at TU Wien ........................................................ 13 2 Visa ....................................................................................................13 3 Linguistic Requirements .................................................................... -

Jewish Communities of Leopoldstadt and Alsergrund

THE VIENNA PROJECT: JEWISH COMMUNITIES OF LEOPOLDSTADT AND ALSERGRUND Site 1A: Introduction to Jewish Life in Leopoldstadt Leopoldstadt, 1020 The history of Jews in Austria is one of repeated exile (der Vertreibene) and return. In 1624, after years and years of being forbidden from living in Vienna, Emperor Ferdinand III decided that Jewish people could return to Vienna but would only be allowed to live in one area outside of central Vienna. That area was called “Unterer Werd” and later became the district of Leopoldstadt. In 1783, Joseph II’s “Toleranzpatent” eased a lot of the restrictions that kept Jews from holding certain jobs or owning homes in areas outside of Leopoldstadt. As a result, life in Vienna became much more open and pleasant for Jewish people, and many more Jewish immigrants began moving to Vienna. Leopoldstadt remained the cultural center of Jewish life, and was nicknamed “Mazzeinsel” after the traditional Jewish matzo bread. Jews made up 40% of the people living in the 2nd district, and about 29% of the city’s Jewish population lived there. A lot of Jewish businesses were located in Leopoldstadt, as well as many of the city’s synagogues and temples. Tens of thousands of Galician Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe made their home there, and brought many of their traditions (such as Yiddish literature) with them. Questions to Consider Look up the history of Jewish eXile and return in Vienna. How many times were they sent away from the city, and why did the city let them return? What were some of the restrictions on Jewish life in Vienna before the “Toleranzpatent” in 1783? What further rights did Jewish people gain in 1860? How did this affect Jewish life and culture in Vienna in the late 1800s and early 1900s? Describe the culture of Leopoldstadt before 1938. -

Step 2025 Urban Development Plan Vienna

STEP 2025 URBAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN VIENNA TRUE URBAN SPIRIT FOREWORD STEP 2025 Cities mean change, a constant willingness to face new develop- ments and to be open to innovative solutions. Yet urban planning also means to assume responsibility for coming generations, for the city of the future. At the moment, Vienna is one of the most rapidly growing metropolises in the German-speaking region, and we view this trend as an opportunity. More inhabitants in a city not only entail new challenges, but also greater creativity, more ideas, heightened development potentials. This enhances the importance of Vienna and its region in Central Europe and thus contributes to safeguarding the future of our city. In this context, the new Urban Development Plan STEP 2025 is an instrument that offers timely answers to the questions of our present. The document does not contain concrete indications of what projects will be built, and where, but offers up a vision of a future Vienna. Seen against the background of the city’s commit- ment to participatory urban development and urban planning, STEP 2025 has been formulated in a broad-based and intensive process of dialogue with politicians and administrators, scientists and business circles, citizens and interest groups. The objective is a city where people live because they enjoy it – not because they have to. In the spirit of Smart City Wien, the new Urban Development Plan STEP 2025 suggests foresighted, intelli- gent solutions for the future-oriented further development of our city. Michael Häupl Mayor Maria Vassilakou Deputy Mayor and Executive City Councillor for Urban Planning, Traffic &Transport, Climate Protection, Energy and Public Participation FOREWORD STEP 2025 In order to allow for high-quality urban development and to con- solidate Vienna’s position in the regional and international context, it is essential to formulate clearcut planning goals and to regu- larly evaluate the guidelines and strategies of the city. -

Die Vergangenheit Ist Immer Präsent / the Past Is Always Present

Die Vergangenheit ist immer präsent The Past is Always Present Ein Besuch im Klub der österreichischen Pensionisten in Tel Aviv und im Büro der Vereinigung der Pensionisten aus Österreich in Israel im August 2015 A visit to the Club of the Austrian Pensioners in Tel Aviv and the office of the Association of Pensioners from Austria in Israel, August 2015. „Echad, steim, schalosch …“, sagt die Gymnastiklehrerin “Echad, steim, schalosch …” The gym teacher calls out den österreichischen PensionistInnen die Übungen an – im Hin- the exercises to the Austrian pensioners, in the background music tergrund läuft leise Musik, eine der turnenden Damen erkennt is playing softly. One of the ladies recognizes the melody and die Melodie und beginnt mitzusummen. Noch zwei Übungen, begins to hum along. Two more exercises, then there will be a dann gibt es eine kurze Pause. Sie ist mehr als willkommen, Kaf- short and much-welcomed break. Coffee and cake are ready and fee und Kuchen stehen bereit – Zeit, Neuigkeiten über die „alte“ waiting. It’s time to exchange news about the “old country” and und die „neue“ Heimat auszutauschen. Der Austausch ist wich- the “new” homeland. These conversations are important and the tig, man kennt sich schon lange: „… dass man hier mit Leuten people have known each other for a long time: “…to get together zusammenkommt. Wir alle haben das gleiche Schicksal. Wir with people here. We all share the same fate. We all came here at sind alle mehr oder weniger zur gleichen Zeit – 1938/1939 – the same time, more or less – 1938/1939.” When someone pays hergekommen.“ Kommt Besuch aus Österreich, ist die alte Hei- a visit from Austria, the “old country” becomes even more pre- mat umso präsenter.