Congressional Access to Information: Using Legislative Will and Leverage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advice and Dissent: Due Process of the Senate

DePaul Law Review Volume 23 Issue 2 Winter 1974 Article 5 Advice and Dissent: Due Process of the Senate Luis Kutner Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation Luis Kutner, Advice and Dissent: Due Process of the Senate, 23 DePaul L. Rev. 658 (1974) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol23/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ADVICE AND DISSENT: DUE PROCESS OF THE SENATE Luis Kutner* The Watergate affair demonstrates the need for a general resurgence of the Senate's proper role in the appointive process. In order to understand the true nature and functioning of this theoretical check on the exercise of unlimited Executive appointment power, the author proceeds through an analysis of the Senate confirmation process. Through a concurrent study of the Senate's constitutionally prescribed function of advice and consent and the historicalprecedent for Senatorial scrutiny in the appointive process, the author graphically describes the scope of this Senatorialpower. Further, the author attempts to place the exercise of the power in perspective, sug- gesting that it is relative to the nature of the position sought, and to the na- ture of the branch of government to be served. In arguing for stricter scrutiny, the author places the Senatorial responsibility for confirmation of Executive appointments on a continuum-the presumption in favor of Ex- ecutive choice is greater when the appointment involves the Executive branch, to be reduced proportionally when the position is either quasi-legis- lative or judicial. -

Annual Report 2018

2018Annual Report Annual Report July 1, 2017–June 30, 2018 Council on Foreign Relations 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10065 tel 212.434.9400 1777 F Street, NW, Washington, DC 20006 tel 202.509.8400 www.cfr.org [email protected] OFFICERS DIRECTORS David M. Rubenstein Term Expiring 2019 Term Expiring 2022 Chairman David G. Bradley Sylvia Mathews Burwell Blair Effron Blair Effron Ash Carter Vice Chairman Susan Hockfield James P. Gorman Jami Miscik Donna J. Hrinak Laurene Powell Jobs Vice Chairman James G. Stavridis David M. Rubenstein Richard N. Haass Vin Weber Margaret G. Warner President Daniel H. Yergin Fareed Zakaria Keith Olson Term Expiring 2020 Term Expiring 2023 Executive Vice President, John P. Abizaid Kenneth I. Chenault Chief Financial Officer, and Treasurer Mary McInnis Boies Laurence D. Fink James M. Lindsay Timothy F. Geithner Stephen C. Freidheim Senior Vice President, Director of Studies, Stephen J. Hadley Margaret (Peggy) Hamburg and Maurice R. Greenberg Chair James Manyika Charles Phillips Jami Miscik Cecilia Elena Rouse Nancy D. Bodurtha Richard L. Plepler Frances Fragos Townsend Vice President, Meetings and Membership Term Expiring 2021 Irina A. Faskianos Vice President, National Program Tony Coles Richard N. Haass, ex officio and Outreach David M. Cote Steven A. Denning Suzanne E. Helm William H. McRaven Vice President, Philanthropy and Janet A. Napolitano Corporate Relations Eduardo J. Padrón Jan Mowder Hughes John Paulson Vice President, Human Resources and Administration Caroline Netchvolodoff OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, Vice President, Education EMERITUS & HONORARY Shannon K. O’Neil Madeleine K. Albright Maurice R. Greenberg Vice President and Deputy Director of Studies Director Emerita Honorary Vice Chairman Lisa Shields Martin S. -

How First-Term Members Enter the House Burdett

Coming into the Country: How First-Term Members Enter the House Burdett Loomis University of Kansas and The Brookings Institution November 17, 2000 In mulling over how newly elected Members of Congress (henceforth MCs1) “enter” the U.S. House of Representatives, I have been drawn back to John McPhee’s classic book on Alaska, Coming into the Country. Without pushing the analogy too far, the Congress is a lot like Alaska, especially for a greenhorn. Congress is large, both in terms of numbers (435 members and 8000 or so staffers) and geographic scope (from Seattle to Palm Beach, Manhattan to El Paso). Even Capitol Hill is difficult to navigate, as it requires a good bit of exploration to get the lay of the land. The congressional wilderness is real, whether in unexplored regions of the Rayburn Building sub-basements or the distant corridors of the fifth floor of the Cannon Office Building, where a sturdy band of first-term MCs must establish their Washington outposts. Although both the state of Alaska and the House of Representatives are governed by laws and rules, many tricks of survival are learned informally -- in a hurried conversation at a reception or at the House gym, in the wake of a pick-up basketball game. In the end, there’s no single understanding of Alaska – it’s too big, too complex. Nor is there any single way to grasp the House. It’s partisan, but sometimes resistant to partisanship. It’s welcoming and alienating. It’s about Capitol Hill, but also about 435 distinct constituencies. -

John Mitchell and the Crimes of Watergate Reconsidered Gerald Caplan Pacific Cgem Orge School of Law

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons McGeorge School of Law Scholarly Articles McGeorge School of Law Faculty Scholarship 2010 The akM ing of the Attorney General: John Mitchell and the Crimes of Watergate Reconsidered Gerald Caplan Pacific cGeM orge School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/facultyarticles Part of the Legal Biography Commons, and the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation 41 McGeorge L. Rev. 311 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the McGeorge School of Law Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in McGeorge School of Law Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book Review Essay The Making of the Attorney General: John Mitchell and the Crimes of Watergate Reconsidered Gerald Caplan* I. INTRODUCTION Shortly after I resigned my position as General Counsel of the District of Columbia Metropolitan Police Department in 1971, I was startled to receive a two-page letter from Attorney General John Mitchell. I was not a Department of Justice employee, and Mitchell's acquaintance with me was largely second-hand. The contents were surprising. Mitchell generously lauded my rather modest role "in developing an effective and professional law enforcement program for the District of Columbia." Beyond this, he added, "Your thoughtful suggestions have been of considerable help to me and my colleagues at the Department of Justice." The salutation was, "Dear Jerry," and the signature, "John." I was elated. I framed the letter and hung it in my office. -

Ethyl Alcohol and Mixtures Thereof: Assessment Regarding the Indigenous Percentage Requirements for Imports in Section 423 of the Tax Reform Act of 1986

ETHYL ALCOHOL AND MIXTURES THEREOF: ASSESSMENT REGARDING THE INDIGENOUS PERCENTAGE REQUIREMENTS FOR IMPORTS IN SECTION 423 OF THE TAX REFORM ACT OF 1986 Report to Congress on Investigation No. 332-261 Under Section 332 (g) of the Tariff Act of 1930 USITC PUBLICATION 2161 FEBRUARY 1989 United States International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL TRADE COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Anne E. Brunsdale, Acting Chairman Alfred E. Eckes Seeley G. Lodwick David B. Rohr Ronald A. Cass Don E. Newquist Office of Industries Vern Simpson, Acting Director This report was prepared principally by Edmund Cappuccilli and Stephen Wanser Project Leaders Antoinette James, Aimison Jonnard, Eric Land and Dave Michels, Office of Industries and Joseph Francois, Office of Economics with assistance from Wanda Tolson, Office of Industries Under the direction of John J. Gersic, Chief Energy and Chemicals Division Address all communications to Kenneth R. Mason, Secretary to the Commission United States International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 PREFACE On September 23, 1988, the United States International Trade Commission, as required by section 1910 of the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988 (P.L. 100-418), 1 instituted investigation No. 332-261, Ethyl Alcohol and Mixtures Thereof: Assessment Regarding the Indigenous Percentage Requirements for Imports in Section 423 of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, under section 332(g) of the Tariff Act of 1930 (19 U.S.C. 1332(g)). Congress directed the Commission and the Comptroller -

Union Calendar No. 607

1 Union Calendar No. 607 110TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 110–934 REPORT ON THE LEGISLATIVE AND OVERSIGHT ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS DURING THE 110TH CONGRESS JANUARY 2, 2009.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 79–006 WASHINGTON : 2009 VerDate Nov 24 2008 22:51 Jan 06, 2009 Jkt 079006 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HR934.XXX HR934 sroberts on PROD1PC70 with HEARING E:\Seals\Congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS CHARLES B. RANGEL, New York, Chairman FORTNEY PETE STARK, California JIM MCCRERY, Louisiana SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan WALLY HERGER, California JIM MCDERMOTT, Washington DAVE CAMP, Michigan JOHN LEWIS, Georgia JIM RAMSTAD, Minnesota RICHARD E. NEAL, Massachusetts SAM JOHNSON, Texas MICHAEL R. MCNULTY, New York PHIL ENGLISH, Pennsylvania JOHN S. TANNER, Tennessee JERRY WELLER, Illinois XAVIER BECERRA, California KENNY C. HULSHOF, Missouri LLOYD DOGGETT, Texas RON LEWIS, Kentucky EARL POMEROY, North Dakota KEVIN BRADY, Texas STEPHANIE TUBBS JONES, Ohio THOMAS M. REYNOLDS, New York MIKE THOMPSON, California PAUL RYAN, Wisconsin JOHN B. LARSON, Connecticut ERIC CANTOR, Virginia RAHM EMANUEL, Illinois JOHN LINDER, Georgia EARL BLUMENAUER, Oregon DEVIN NUNES, California RON KIND, Wisconsin PAT TIBERI, Ohio BILL PASCRELL, JR., New Jersey JON PORTER, Nevada SHELLY BERKLEY, Nevada JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York CHRIS VAN HOLLEN, Maryland KENDRICK MEEK, Florida ALLYSON Y. SCHWARTZ, Pennsylvania ARTUR DAVIS, Alabama (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:20 Jan 06, 2009 Jkt 079006 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 E:\HR\OC\HR934.XXX HR934 sroberts on PROD1PC70 with HEARING LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL U.S. -

June 1-15, 1972

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/2/1972 A Appendix “B” 2 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/5/1972 A Appendix “A” 3 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/6/1972 A Appendix “A” 4 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/9/1972 A Appendix “A” 5 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/12/1972 A Appendix “B” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-10 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary June 1, 1972 – June 15, 1972 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION *U.S. GPO; 1989-235-084/00024 NA 14021 (4-85) THF WHITE ,'OUSE PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON'S DAILY DIARY (Sec Travel Record for Travel AnivilY) f PLACE DAY BEGAN DATE (Mo., Day. Yr.) _u.p.-1:N_E I, 1972 WILANOW PALACE TIME DAY WARSAW, POLi\ND 7;28 a.m. THURSDAY PHONE TIME P=Pl.ccd R=Received ACTIVITY 1----.,------ ----,----j In Out 1.0 to 7:28 P The President requested that his Personal Physician, Dr. -

Ryan White CARE Act, Donna Elaine Sweet, MD, MACP, AAHIVS the Nation Embarks on Historic E Xecutive Director Health Care Reform James Friedman, MHA by HOLLY A

The AmericAn AcAdemy of HiV medicine HIV® S p ecIalist Ryan Patient Care, PraCtiCe ManageMent & Professional Development inforMation for HIV Care ProviDers Summer 2010 www.aahivm.org White Lives Saved, the Battle Continues 340B Pharmacies 3 Health Care Reform & HIV 4 National HIV/AIDS Strategy 8 Deborah Parham Hopson 11 By JaMes M. friedman, MHa, ExEcutivE dirEctor, aahivm LetteR fRom tHe DIR e c t OR Secretary Sebelius and President obama making a Commitment to the HIV Workforce n June, Health and Human Services panded routine testing, is a recipe for disaster. (HHS) Secretary Kathleen Sebelius and Additionally, the anticipated influx of patients Health Resources and Services Admin- resulting from the implementation of many of istration Administrator Mary Wakefield the health reform provisions in 2014 must be Iannounced a one-time investment of $250 mil- met with new and qualified providers. lion to strengthen the primary care workforce. HIV/AIDS workforce continues to be a This new money came from a $500 million high policy priority for the Academy. We have Prevention and Public Health Fund which was engaged Congress and advocated for the ex- a part of the new health reform law that passed pansion of the National Health Service Corps, this year (The Patient Protection and Afford- James Friedman and are pleased to see that the new health re- able Care Act). This investment is not to be confused with form law provides for growth in both funding and capacity the $1.3 billion authorized over five years for the National of the Corps in the future —a move that will certainly help Health Service Corps (also in the health reform bill), or the increase the number of HIV practitioners. -

H. Doc. 108-222

EIGHTEENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1823, TO MARCH 3, 1825 FIRST SESSION—December 1, 1823, to May 27, 1824 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1824, to March 3, 1825 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—DANIEL D. TOMPKINS, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—JOHN GAILLARD, 1 of South Carolina SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—CHARLES CUTTS, of New Hampshire SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—MOUNTJOY BAYLY, of Maryland SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—HENRY CLAY, 2 of Kentucky CLERK OF THE HOUSE—MATTHEW ST. CLAIR CLARKE, 3 of Pennsylvania SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS DUNN, of Maryland; JOHN O. DUNN, 4 of District of Columbia DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—BENJAMIN BIRCH, of Maryland ALABAMA GEORGIA Waller Taylor, Vincennes SENATORS SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES William R. King, Cahaba John Elliott, Sunbury Jonathan Jennings, Charlestown William Kelly, Huntsville Nicholas Ware, 8 Richmond John Test, Brookville REPRESENTATIVES Thomas W. Cobb, 9 Greensboro William Prince, 14 Princeton John McKee, Tuscaloosa REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Gabriel Moore, Huntsville Jacob Call, 15 Princeton George W. Owen, Claiborne Joel Abbot, Washington George Cary, Appling CONNECTICUT Thomas W. Cobb, 10 Greensboro KENTUCKY 11 SENATORS Richard H. Wilde, Augusta SENATORS James Lanman, Norwich Alfred Cuthbert, Eatonton Elijah Boardman, 5 Litchfield John Forsyth, Augusta Richard M. Johnson, Great Crossings Henry W. Edwards, 6 New Haven Edward F. Tattnall, Savannah Isham Talbot, Frankfort REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Wiley Thompson, Elberton REPRESENTATIVES Noyes Barber, Groton Samuel A. Foote, Cheshire ILLINOIS Richard A. Buckner, Greensburg Ansel Sterling, Sharon SENATORS Henry Clay, Lexington Ebenezer Stoddard, Woodstock Jesse B. Thomas, Edwardsville Robert P. Henry, Hopkinsville Gideon Tomlinson, Fairfield Ninian Edwards, 12 Edwardsville Francis Johnson, Bowling Green Lemuel Whitman, Farmington John McLean, 13 Shawneetown John T. -

JUNE 10, 2019 Chairman Nadler, Ranking Member Collins, the Last

STATEMENT OF JOHN W. DEAN U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HEARINGS: “LESSONS FROM THE MUELLER REPORT: PRESIDENTIAL OBSTRUCTION AND OTHER CRIMES.” JUNE 10, 2019 Chairman Nadler, Ranking Member Collins, the last time I appeared before your committee was July 11, 1974, during the impeachment inquiry of President Richard Nixon. Clearly, I am not here as a fact witness. Rather I accepted the invitation to appear today because I hope I can give a bit of historical context to the Mueller Report. In many ways the Mueller Report is to President Trump what the so-called Watergate “Road Map” (officially titled “Grand Jury Report and Recommendation Concerning Transmission of Evidence to the House of Representatives”) was to President Richard Nixon. Stated a bit differently, Special Counsel Mueller has provided this committee a road map. The Mueller Report, like the Watergate Road Map, conveys findings, with supporting evidence, of potential criminal activity based on the work of federal prosecutors, FBI investigators, and witness testimony before a federal grand jury. The Mueller Report explains – in Vol. II, p. 1 – that one of the reasons the Special Counsel did not make charging decisions relating to obstruction of justice was because he did not want to “potentially preempt [the] constitutional processes for addressing presidential misconduct.” The report then cites at footnote 2: “See U.S. CONST. ART. I § 2, cl. 5; § 3, cl. 6; cf. OLC Op. at 257-258 (discussing relationship between impeachment and criminal prosecution of a sitting President).” Today, you are focusing on Volume II of the report. -

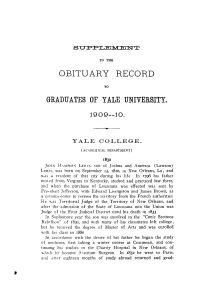

Obituary Record

S U TO THE OBITUARY RECORD TO GRADUATES OF YALE UNIVEESITY. 1909—10. YALE COLLEGE. (ACADEMICAL DEPARTMENT) 1832 JOHN H \MPDFN LEWIS, son of Joshua and America (Lawson) Lewis, was born on September 14, 1810, m New Orleans, La, and was a resident of that city during his life In 1796 his father moved from Virginia to Kentucky, studied and practiced law there, and when the purchase of Louisiana was effected was sent by President Jefferson, with Edward Livingston and James Brown, as a commisMoner to receive the territory from the French authorities He was Territorial Judge of the Territory of New Orleans, and after the admission of the State of Louisiana into the Union was Judge of the First Judicial District until his death in 1833 In Sophomore year the son was involved in the "Conic Sections Rebellion" of 1830, and with many of his classmates left college, but he received the degree of Master of Arts and was enrolled with his class in 1880 In accordance with the desire of his father he began the study of medicine, first taking a winter course at Cincinnati, and con- tinuing his studies in the Charity Hospital in New Orleans, of which he became Assistant Surgeon In 1832 he went to Pans, and after eighteen months of study abroad returned and grad- YALE COLLEGE 1339 uated in 1836 with the first class from the Louisiana Medical College After having charge of a private infirmary for a time he again went abroad for further study In order to obtain the nec- essary diploma in arts and sciences he first studied in the Sorbonne after which he entered -

Toni Swanger Papers, 1951-1998

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Anne Fracassa October 13, 1988 371-6522 AREA GROUP / Mrs. Carol Smith, Co-Chairman of Detroit Chapter Right-to-Life, that her organization is doing everything possib ~to support the efforts of the Michigan Committee to End Tax-Funded Abortions ~ ~f;?o Jr~~ •:our purpose is to encourage the people of Wayne County and surrounding areas to vote "YES" on Proposal A on November 8th to end elective tax-funded abortions in Michigan.", Mrs. Smith said. "We want to do our part toward putting this Lj . - cJ-6/-;2 Js-? issue to rest once and for all." ~JP/U.-~/ , ~~ She noted that, "Thirty-six states have already decided that taxpayers shouldn't have to pay for elective Medicaid abortions. Michigan is the only state in the Midwest that still uses tax funds for this purpose. We believe Michigan's citizens shouldn't have to pay for elective abortions." Over the past 10 years, the Michigan Legislature has voted 17 times to end state funding of Medicaid abortions, but gubernatorial vetoes have allowed them to continue. "The legislature obviously feels this is bad tax policy, and recent polls indicate that a majority of Michigan's citizens feel that way too," Mrs. Smith said. ''A 'YES' vote on Proposal A will get Michigan out of the $6 million-a-year Medicaid abortion business, and we believe the 'YES' vote will prevail November 8th. l"i37i]. Vote "Yes" on "A" ~ End Tax-Funded Abortions NEWS from The Committee to End Tax-Funded Abortions MEDIA CONTACT: For Immediate Release John Wilson October 14, 1988 (517) 487-3376 LEGISLATORS, NATIONAL EXPERT QUESTION PRO-TAX ABORTION CAMPAIGN FOCUS AND COST SCARE TACTICS Lansing, MI.