Timber in the Russian Far East and Potential Transborder Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russia and the Eurasian Republics THIS REGION Spans the Continents of Europe and Asia

390-391 U5 CH14 UO TWIP-860976 3/15/04 5:21 AM Page 390 Unit Workers on the statue Russians in front of Motherland Calls, St. Basil’s Cathedral, Volgograd Moscow 224 390-391 U5 CH14 UO TWIP-860976 3/15/04 5:22 AM Page 391 RussiaRussia andand the the EurasianEurasian f you had to describe Russia RepublicsRepublics Iin one word, that word would be BIG! Russia is the largest country in the world in area. Its almost 6.6 million square miles (17 million sq. km) are spread across two continents—Europe and Asia. As you can imagine, such a large country faces equally large challenges. In 1991 Russia emerged from the Soviet Union as an independent country. Since then it has been struggling to unite its many ethnic groups, set up a demo- cratic government, and build a stable economy. ▼ Siberian tiger in a forest NGS ONLINE in eastern Russia www.nationalgeographic.com/education 225 392-401 U5 CH14 RA TWIP-860976 3/15/04 5:28 AM Page 392 REGIONAL ATLAS Focus on: Russia and the Eurasian Republics THIS REGION spans the continents of Europe and Asia. It includes Russia—the world’s largest country—and the neigh- boring independent republics of Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. Russia and the Eurasian republics cover about 8 million square miles (20.7 million sq. km). This is greater than the size of Canada, the United States, and Mexico combined. The Caspian Sea is actually a salt lake that lies at the base of the Caucasus Mountains in The Land Russia’s southwest. -

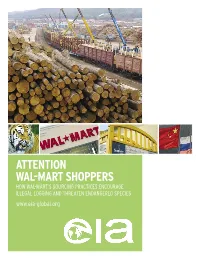

Attention Wal-Mart Shoppers How Wal-Mart’S Sourcing Practices Encourage Illegal Logging and Threaten Endangered Species Contents © Eia

ATTENTION WAL-MART SHOPPERS HOW WAL-MART’S SOURCING PRACTICES ENCOURAGE ILLEGAL LOGGING AND THREATEN ENDANGERED SPECIES www.eia-global.org CONTENTS © EIA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Copyright © 2007 Environmental Investigation Agency, Inc. No part of this publication may be 2 INTRODUCTION: WAL-MART IN THE WOODS reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Environmental 4 THE IMPACTS OF ILLEGAL LOGGING Investigation Agency, Inc. Pictures on pages 8,10,11,14,15,16 were published in 6 LOW PRICES, HIGH CONTROL: WAL-MART’S BUSINESS MODEL The Russian Far East, A Reference Guide for Conservation and Development, Josh Newell, 6 REWRITING THE RULES OF THE SUPPLIER-RETAILER RELATIONSHIP 2004, published by Daniel & Daniel, Publishers, Inc. 6 SQUEEZING THE SUPPLY CHAIN McKinleyville, California, 2004. ENVIRONMENTAL INVESTIGATION AGENCY 7 BIG FOOTPRINT, BIG PLANS: WAL-MART’S ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT 7 THE FOOTPRINT OF A GIANT PO Box 53343, Washington DC 20009, USA 7 STEPS FORWARD Tel: +1 202 483 6621 Fax: +1 202 986 8626 Email: [email protected] 8 GLOBAL REACH: WAL-MART’S SALE OF WOOD PRODUCTS Web: www.eia-global.org 8 A SNAPSHOT INTO WAL-MART’S WOOD BUYING AND RETAIL 62-63 Upper Street, London N1 ONY, UK 8 WAL-MART AND CHINESE EXPORTS 8 THE RISE OF CHINA’S WOOD PRODUCTS INDUSTRY Tel: +44(0)20 7354 7960 Fax: +44(0)20 7354 7961 10 CHINA IMPORTS RUSSIA’S GREAT EASTERN FORESTS Email: [email protected] 10 THE WILD WILD FAR EAST 11 CHINA’S GLOBAL SOURCING Web: www.eia-international.org 10 IRREGULARITIES FROM FOREST TO FRONTIER 14 ECOLOGICAL AND SOCIAL IMPACTS 15 THE FLOOD OF LOGS ACROSS THE BORDER 17 LONGJIANG SHANGLIAN: BRIEFCASES OF CASH FOR FORESTS 18 A LANDSCAPE OF WAL-MART SUPPLIERS: INVESTIGATION CASE STUDIES 18 BABY CRIBS 18 DALIAN HUAFENG FURNITURE CO. -

Catalogue of Exporters of Primorsky Krai № ITN/TIN Company Name Address OKVED Code Kind of Activity Country of Export 1 254308

Catalogue of exporters of Primorsky krai № ITN/TIN Company name Address OKVED Code Kind of activity Country of export 690002, Primorsky KRAI, 1 2543082433 KOR GROUP LLC CITY VLADIVOSTOK, PR-T OKVED:51.38 Wholesale of other food products Vietnam OSTRYAKOVA 5G, OF. 94 690001, PRIMORSKY KRAI, 2 2536266550 LLC "SEIKO" VLADIVOSTOK, STR. OKVED:51.7 Other ratailing China TUNGUS, 17, K.1 690003, PRIMORSKY KRAI, VLADIVOSTOK, 3 2531010610 LLC "FORTUNA" OKVED: 46.9 Wholesale trade in specialized stores China STREET UPPERPORTOVA, 38- 101 690003, Primorsky Krai, Vladivostok, Other activities auxiliary related to 4 2540172745 TEK ALVADIS LLC OKVED: 52.29 Panama Verkhneportovaya street, 38, office transportation 301 p-303 p 690088, PRIMORSKY KRAI, Wholesale trade of cars and light 5 2537074970 AVTOTRADING LLC Vladivostok, Zhigura, 46 OKVED: 45.11.1 USA motor vehicles 9KV JOINT-STOCK COMPANY 690091, Primorsky KRAI, Processing and preserving of fish and 6 2504001293 HOLDING COMPANY " Vladivostok, Pologaya Street, 53, OKVED:15.2 China seafood DALMOREPRODUKT " office 308 JOINT-STOCK COMPANY 692760, Primorsky Krai, Non-scheduled air freight 7 2502018358 OKVED:62.20.2 Moldova "AVIALIFT VLADIVOSTOK" CITYARTEM, MKR-N ORBIT, 4 transport 690039, PRIMORSKY KRAI JOINT-STOCK COMPANY 8 2543127290 VLADIVOSTOK, 16A-19 KIROV OKVED:27.42 Aluminum production Japan "ANKUVER" STR. 692760, EDGE OF PRIMORSKY Activities of catering establishments KRAI, for other types of catering JOINT-STOCK COMPANY CITYARTEM, STR. VLADIMIR 9 2502040579 "AEROMAR-ДВ" SAIBEL, 41 OKVED:56.29 China Production of bread and pastry, cakes 690014, Primorsky Krai, and pastries short-term storage JOINT-STOCK COMPANY VLADIVOSTOK, STR. PEOPLE 10 2504001550 "VLADHLEB" AVENUE 29 OKVED:10.71 China JOINT-STOCK COMPANY " MINING- METALLURGICAL 692446, PRIMORSKY KRAI COMPLEX DALNEGORSK AVENUE 50 Mining and processing of lead-zinc 11 2505008358 " DALPOLIMETALL " SUMMER OCTOBER 93 OKVED:07.29.5 ore Republic of Korea 692183, PRIMORSKY KRAI KRAI, KRASNOARMEYSKIY DISTRICT, JOINT-STOCK COMPANY " P. -

Russian Federation As Central Planner: Case Study of Investments Into the Russian Far East in Anticipation of the 2012 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Conference

Russian Federation as Central Planner: Case Study of Investments into the Russian Far East in Anticipation of the 2012 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Conference Anne Thorsteinson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Studies: Russia, East Europe and Central Asia University of Washington 2012 Committee: Judith Thornton, Chair Craig ZumBrunnen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Jackson School of International Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Figures ii List of Tables iii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: An Economic History of the Russian Far East 6 Chapter 2: Primorsky Krai Today 24 Chapter 3: The Current Federal Reform Program 30 Chapter 4: Economic Indicators in Primorsky Krai 43 Chapter 5: Conclusion 54 Bibliography 64 LIST OF FIGURES Page 1. Primorsky Krai: Sown Area of Crops 21 2. Far East Federal Region: Sown Area of Crops 21 3. Primorye Agricultural Output 21 4. Russian Federal Fisheries Production 22 5. Vladivostok: Share of Total Exports by Type, 2010 24 6. Vladivostok: Share of Total Imports by Type, 2010 24 7. Cost of a Fixed Basket of Consumer Goods and Services as a Percentage of the All Russian Average 43 8. Cost of a Fixed Basked of Consumer Goods and Services 44 9. Per Capita Monthly Income 45 10. Per Capita Income in Primorsky Krai as a Percentage of the All Russian Average 45 11. Foreign Direct Investment in Primorsky Krai 46 12. Unemployed Proportion of Economically Active Population in Primorsky Krai 48 13. Students in State Institutions of Post-secondary Education in Primorsky Krai 51 14. -

Russia: the Impact of Climate Change to 2030: Geopolitical Implications

This paper does not represent US Government views. This page is intentionally kept blank. This paper does not represent US Government views. This paper does not represent US Government views. Russia: The Impact of Climate Change to 2030: Geopolitical Implications Prepared jointly by CENTRA Technology, Inc., and Scitor Corporation The National Intelligence Council sponsors workshops and research with nongovernmental experts to gain knowledge and insight and to sharpen debate on critical issues. The views expressed in this report do not reflect official US Government positions. CR 2009-16 September 2009 This paper does not represent US Government views. This paper does not represent US Government views. This page is intentionally kept blank. This paper does not represent US Government views. This paper does not represent US Government views. Scope Note Following the publication in 2008 of the National Intelligence Assessment on the National Security Implications of Global Climate Change to 2030, the National Intelligence Council (NIC) embarked on a research effort to explore in greater detail the national security implications of climate change in six countries/regions of the world: India, China, Russia, North Africa, Mexico and the Caribbean, and Southeast Asia and the Pacific Island States. For each country/region we have adopted a three-phase approach. • In the first phase, contracted research explores the latest scientific findings on the impact of climate change in the specific region/country. For Russia, the Phase I effort was published as a NIC Special Report: Russia: Impact of Climate Change to 2030, A Commissioned Research Report (NIC 2009-04, April 2009). • In the second phase, a workshop or conference composed of experts from outside the Intelligence Community (IC) determines if anticipated changes from the effects of climate change will force inter- and intra-state migrations, cause economic hardship, or result in increased social tensions or state instability within the country/region. -

Conservation Investment Strategy for the Russian Far East AUTHORSHIP and ATTRIBUTION

SASHA LEAHOVCENCO PACIFIC ENVIRONMENT DAVID LAWSON, WWF ELAINE R. WILSON Conservation Investment Strategy Strategy Investment Conservation EXECUTIVE SUMMARY for the Russian Far East Far for the Russian Pacific Environment Pacific 2 Conservation Investment Strategy for the Russian Far East AUTHORSHIP AND ATTRIBUTION Executive Editors: Evan Sparling (Pacific Environment) Eugene Simonov (Pacific Environment, Rivers Without Boundaries) Project Coordinating Team: Eduard Zdor (Chukotka Association of Traditional Marine Mammal Hunters) Dmitry Lisitsyn (Sakhalin Environment Watch) Anatoly Lebedev (Bureau for Regional Outreach Campaigns) Sergey Shapkhaev (Buryat Regional Association for Baikal) Peer Review Group: Alan Holt (Margaret A. Cargill Foundation) David Gordon (Goldman Environmental Prize) Xanthippe Augerot (Pangaea Environmental LLC.) Peter Riggs (Pivot Point) Jack Tordoff (Critical Ecosystems Partnership Fund) Dmitry Lisitsyn (Sakhalin Environment Watch) Conservation Planning Expert: Nicole Portley (Sustainable Fisheries Partnership) Writing and Design: John Byrne Barry Additional Writing and Translating: Sonya Kleshik Special thanks to the following for their contributions to this assessment: Marina Rikhvanova (Baikal Environment Wave), Maksim Chakilev, Yuri Khokhlov, Anatoly Kochnev (Chukotka Branch of the Pacific Ocean Institute for Fisheries and Oceanography), Natalya Shevchenko (Chukotka Regional Department of the Environment (retired)), Oleg Goroshko (Daursky Biosphere Reserve), Elena Tvorogova (Foundation for Revival of Siberian -

China Russia

1 1 1 1 Acheng 3 Lesozavodsk 3 4 4 0 Didao Jixi 5 0 5 Shuangcheng Shangzhi Link? ou ? ? ? ? Hengshan ? 5 SEA OF 5 4 4 Yushu Wuchang OKHOTSK Dehui Mudanjiang Shulan Dalnegorsk Nongan Hailin Jiutai Jishu CHINA Kavalerovo Jilin Jiaohe Changchun RUSSIA Dunhua Uglekamensk HOKKAIDOO Panshi Huadian Tumen Partizansk Sapporo Hunchun Vladivostok Liaoyuan Chaoyang Longjing Yanji Nahodka Meihekou Helong Hunjiang Najin Badaojiang Tong Hua Hyesan Kanggye Aomori Kimchaek AOMORI ? ? 0 AKITA 0 4 DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE'S 4 REPUBLIC OF KOREA Akita Morioka IWATE SEA O F Pyongyang GULF OF KOREA JAPAN Nampo YAMAJGATAA PAN Yamagata MIYAGI Sendai Haeju Niigata Euijeongbu Chuncheon Bucheon Seoul NIIGATA Weonju Incheon Anyang ISIKAWA ChechonREPUBLIC OF HUKUSIMA Suweon KOREA TOTIGI Cheonan Chungju Toyama Cheongju Kanazawa GUNMA IBARAKI TOYAMA PACIFIC OCEAN Nagano Mito Andong Maebashi Daejeon Fukui NAGANO Kunsan Daegu Pohang HUKUI SAITAMA Taegu YAMANASI TOOKYOO YELLOW Ulsan Tottori GIFU Tokyo Matsue Gifu Kofu Chiba SEA TOTTORI Kawasaki KANAGAWA Kwangju Masan KYOOTO Yokohama Pusan SIMANE Nagoya KANAGAWA TIBA ? HYOOGO Kyoto SIGA SIZUOKA ? 5 Suncheon Chinhae 5 3 Otsu AITI 3 OKAYAMA Kobe Nara Shizuoka Yeosu HIROSIMA Okayama Tsu KAGAWA HYOOGO Hiroshima OOSAKA Osaka MIE YAMAGUTI OOSAKA Yamaguchi Takamatsu WAKAYAMA NARA JAPAN Tokushima Wakayama TOKUSIMA Matsuyama National Capital Fukuoka HUKUOKA WAKAYAMA Jeju EHIME Provincial Capital Cheju Oita Kochi SAGA KOOTI City, town EAST CHINA Saga OOITA Major Airport SEA NAGASAKI Kumamoto Roads Nagasaki KUMAMOTO Railroad Lake MIYAZAKI River, lake JAPAN KAGOSIMA Miyazaki International Boundary Provincial Boundary Kagoshima 0 12.5 25 50 75 100 Kilometers Miles 0 10 20 40 60 80 ? ? ? ? 0 5 0 5 3 3 4 4 1 1 1 1 The boundaries and names show n and t he designations us ed on this map do not imply of ficial endors ement or acceptance by the United N at ions. -

Subterranean Fauna from Siberia and Russian Far East ______ENCYCLOPAEDIA BIOSPEOLOGICA (Siberia-Far East Special Issue)

Research Article ISSN 2336-9744 (online) | ISSN 2337-0173 (print) The journal is available on line at www.biotaxa.org/em Subterranean fauna from Siberia and Russian Far East _________________ ENCYCLOPAEDIA BIOSPEOLOGICA (Siberia-Far East special Issue) CHRISTIAN JUBERTHIE1, DIMITRI SIDOROV2, VASILE DECU3, ELENA MIKHALJOVA2 & KSENIA SEMENCHENKO2 1Encyclopédie Biospéologique, Edition. 1 Impasse Saint-Jacques, 09190 Saint-Lizier France; e-mail: [email protected] 2Institute of Biology and Soil Science, 100-letiya Vladisvostoka Av. 159, 690022 Vladivostok, Russia; e-mail: [email protected] 3Institutul de Speologie "Emil Racovitza", Academia romana, Calea 13 Septembrie, 13050711 Bucarest, Roumanie Received 20 March 2016 │ Accepted 25 November 2016 │ Published online 29 November 2016. Abstract Description of the main karstic regions of Siberia and Far East, and the most important caves. Survey of the subterranean species collected in caves, springs, hyporheic and MSSh. Relationship with the climate and glacial paleoclimatic periods to explain the paucity of the terrestrial fauna of Siberia. Persistence of some aquatic stygobionts (Crustacea), and richness of the subterranean fauna of the Far East, particularily in the Sikhote-Alin. The Crutaceans of the eastern part of the Ussury basin and Sakhalin Island have relationship with the Japanese and Korean fauna. Key words: karst, caves, springs, MSS, subterranean fauna, biogeography. 1 Generalities and History The study of caves in Siberia was begun in the late 17th century (Tsykin et al., 1979), but the first published report were made as early as in the 18th century by swedish geographer P. von Strahlenberg who in 1722 visited the cave on the Yenisei river bank above Krasnoyarsk and gave a short description, which is considered the first report of caves in Siberia (Strahlenberg, 1730). -

Seaports in Russia

SEAPORTS IN RUSSIA FLANDERS INVESTMENT & TRADE MARKET SURVEY Russian seaports November 2015 André DE RIJCK, Vlaams Economisch Vertegenwoordiger in Moskou Economic Representation of Flanders c/o Embassy of Belgium Mytnaya st. 1, bld.1, entrance 2, 119049 Moscow, RUSSIA T: +7 499 238 60 85/96 | F: +7 499 238 51 15 [email protected] Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Russian largest seaports top-7 by cargo turnover ........................................................................................................... 4 Brief analysis of seaport infrastructure in Russia............................................................................................................. 4 Dynamics of cargo turnover of Russian seaports (2010-2014 yy in mln.tons) ................................................. 5 Cargo turnover structure in 2014 (mln tons, “%” year–on–year changes compared to 2013) ............... 6 The dynamics of cargo turnover by essentials categories in 2013-2014 yy. (in mln.tons) ......................... 7 Structure of the cargo turnover by category in 2014 ..................................................................................................... 8 The cargo turnover structure by Russian ports in 2014 in mln.tons ..................................................................... 9 Russian seaports market share structure -

Ricken and Artificial Selection on Primorsky Krai Territory

Gukov, G.V, Rozlomiy, N.G. /Vol. 8 Núm. 18: 432- 437/ Enero-febrero 2019 432 Articulo de investigación Biological and environmental peculiarities of tricholoma caligatum (viv) ricken and artificial selection on Primorsky Krai territory Particularidades biológicas y ambientales de tricholoma caligatum (viv) ricken y selección artificial en el territorio de Primorsky Krai Particularidades biológicas e ambientais do tricomaloma caligatum (vida) e seleção artificial no território do Krai de Primorsky Recibido: 16 de enero de 2019. Aceptado: 06 de febrero de 2019 Written by: Gukov G.V. (Corresponding Author)133 Rozlomiy N.G.134 Abstract Resumen Matsutake mushroom is unique in many ways - it El hongo Matsutake es único en muchos has several names, including two Latin ones, aspectos: tiene varios nombres, entre ellos dos mycorhiza developer, and selects individual latinos, desarrollador de micorhiza, y selecciona conifers or hardwood specifically as the partners coníferas individuales o madera dura from woody plant species in different countries. específicamente como socios de especies de It is hidden and very shy - the main part of its fruit plantas leñosas en diferentes países. Es oculto y body (leg) is hidden in soil, and the small compact muy tímido: la parte principal de su cuerpo frutal cap of the fungus is not always visible in forest (pierna) está oculta en el suelo, y la pequeña capa among the fallen autumn needles and leaves. The compacta del hongo no siempre es visible en el mushroom is also unique as it has exceptional bosque entre las hojas y las agujas otoñales nutritional and medicinal properties, therefore caídas. El hongo también es único ya que tiene the price for this unique species exceeds all propiedades nutricionales y medicinales reasonable limits. -

Russia's Arctic Cities

? chapter one Russia’s Arctic Cities Recent Evolution and Drivers of Change Colin Reisser Siberia and the Far North fi gure heavily in Russia’s social, political, and economic development during the last fi ve centuries. From the beginnings of Russia’s expansion into Siberia in the sixteenth century through the present, the vast expanses of land to the north repre- sented a strategic and economic reserve to rulers and citizens alike. While these reaches of Russia have always loomed large in the na- tional consciousness, their remoteness, harsh climate, and inaccessi- bility posed huge obstacles to eff ectively settling and exploiting them. The advent of new technologies and ideologies brought new waves of settlement and development to the region over time, and cities sprouted in the Russian Arctic on a scale unprecedented for a region of such remote geography and harsh climate. Unlike in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions of other countries, the Russian Far North is highly urbanized, containing 72 percent of the circumpolar Arctic population (Rasmussen 2011). While the largest cities in the far northern reaches of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland have maximum populations in the range of 10,000, Russia has multi- ple cities with more than 100,000 citizens. Despite the growing public focus on the Arctic, the large urban centers of the Russian Far North have rarely been a topic for discussion or analysis. The urbanization of the Russian Far North spans three distinct “waves” of settlement, from the early imperial exploration, expansion of forced labor under Stalin, and fi nally to the later Soviet development 2 | Colin Reisser of energy and mining outposts. -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town.