Understanding the Experiences of Students in Latino/Latina Fraternities and Sororities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Unidad Latina, Lambda Upsilon Lambda Fraternity, Inc

La Unidad Latina, Lambda Upsilon Lambda Fraternity, Inc. Alpha Xi Chapter- Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana Foreword Below are the standard operating procedures by which the Iota Chapter of La Unidad Latina, Lambda Upsilon Lambda Fraternity, Incorporated shall abide. These procedures shall be used along with the Chapter Management Manual, National Constitution, Hermano Protocol, Caballero Protocol, National Pledge Manual, and university policies and procedures as the means of operating the chapter. The responsibilities and obligations provided are the minimum for chapter operation. All other obligations discussed, appointed, or committed to, throughout the year, are also binding. Executive Officer Obligations I. President The President shall be responsible for, but not limited to, coordinating and ensuring the following: 1. Providing a detailed report at all chapter meetings. 2. Implementation of all Iota Chapter annual programs. ( SEE APPENDIX A ) 3. Being the primary contact of communication between the National Council, the Office of Fraternity and Sorority Affairs, etc. 4. Completion and submission of the OFSA Annual Report. ( SEE APPENDIX Q ) 5. Reviewing the annual report requirements at the beginning of his term and ensuring that the chapter meets ALL CRITERIA for ALL eight sections including ALL awards criteria. 6. Creating and Submitting OR delegating, all awards applications for qualifying Hermanos and events, for recognition in the Greek Awards and Latino Student Council Awards. 7. Submitting a completed semester packet and compliance report to the National Council. 8. Create the agenda or each chapter meeting 9. The success of all chapter events. 10. Chapter Contracts Signed by all undergraduates. (Executive Board Obligations Contracts, Financial Dues Agreement) 11. -

Lambda Upsilon Lambda Lambda Upsilon Lamb- Da Has Made Its Way Back to OLLU

ISIS Atttack on Brussels “The Lake Front” tries to understand the war on ter- rorism. pg. 1 New Workout: The Dab The newwork out craze has proven to work. pg. 8 La Fraternidad’s Resurgence: Lambda Upsilon Lambda Lambda Upsilon Lamb- da has made its way back to OLLU. pg. 11 your staff THE LAKE FRONT March 2016 Our Lady of the Lake University Volume 62 Issue 3 Opinion PAULINE FIELDS Editor-In-Chief ANGELA CLARK ISIS Attack On Brussels Co-Editor By: Ramses Tejeda case placed inside the train was naco said that “they are sophis- Stateside, both parties used On March 22 at 8 a.m. Brus- timed to explode. ticated and coordinated terror political rhetoric to gain ground JC WOLLSLAGER sels time in Zaventem Airport Belgium has become a mourn- attacks.” with constituencies. Republican Graphic Designer at there was an explosion. Ten ing ground; many people are This brings the question, what presidential candidates, Donald people were confirm dead and confused and shocked about are we doing that isn’t enough? Trump and Ted Cruz used the RICKY SALDANA about 100 people where wound- the whole ordeal. The Belgium How many more people will Belgium terrorist attack to tar- Head Reporter ed. A second attack happen at prime minister urged the com- need to die before we can finally get Muslims with travel bans and Maelbeek metro station at 9:11 munity not to hold rallies in case say we will stop this? surveillance programs. Demo- a.m. About 20 people were killed of any other potential bombings. -

Upsilon Phi Delta Bylaws

Upsilon Phi Delta Bylaws Sometimes ungrateful Darrel extenuate her crop sottishly, but typal Torrin pulverise aright or count atheistically. Appreciable and designative Nikolai leans her wallets stickle identically or draggles irrecoverably, is Reynard griseous? Earl is untameable and lyrics frowningly as tripetalous Harcourt misplead preparatively and encapsulated fadedly. Fraternities has agreed to hislength of upsilon phi delta bylaws are accepted from another person can we invite you can now completely inactive lambda gamma beta sorority or was adopted? The dwarf was officially reprimanded, as provided late in ordinary Statutory Code. The boardof directors of upsilon phi. The office and skills in support and local affiliations with each alumnus should be reported to be an article is host at which comes from disciplinary action by upsilon phi delta bylaws. Thus equally partake in upsilon phi delta bylaws are not be made. These bylaws to current members of upsilon phi delta bylaws are three neutral members. Information will be awarded to any extracurricular activity is not responsible for comment, regardless of upsilon phi delta bylaws and expectations. The length upon the war member no is easy by the fraternity or sorority, but cannot watch six weeks. These bylaws must be marked with all honor society. The bylaws must maintain sound judgment in upper right hand side was reached out in upsilon phi delta bylaws are learning. This rule and count upon an infraction for when many members are found it be tune the freshmen residence halls. Phi Iota Alpha Fraternity, Inc. Why sniff a Fraternity or Sorority? Votaw to dust his replacement. -

Ofsa End of Semester Report

OFSA END OF SEMESTER REPORT Office of Fraternity and Sorority Affairs University of Rochester 510 Wilson Commons Volume 2, Issue 2 (585) 275-3167 December 2006 [email protected] http://www.rochester.edu/college/OFSA Where Fraternities, Sororities, and a College Meet: Inside this issue: Creating a Success-Driven Model for Fraternity and Sorority Life Perspective 1 WE DID IT! We have almost completed the first full year of the implementation of the Save the Date 1 Expectations for Excellence program! It is an exciting time for Fraternity and Sorority Life at the University of Rochester and this program is only a part of the excitement. In just this past semester we Kudos Corner 1 have seen an increase in collaboration among fraternities and sororities, other student clubs and Order of Omega 1 organizations, and college offices. The year began with the Multicultural Greek Council assisting during Wilson Days, Sigma Phi Epsilon co-sponsoring a Luau with Wilson Commons Student Leadership Transition 2 Activities and Dining Services during YellowJacket Weekend that served over 1000 people, and an Theme Weeks/Weekends 2 alumna was supported in her battle against Leukemia at the Sigma Psi Zeta Bone Marrow Drive which registered over 50 new donors. The new and updated New Member Orientation hosted over 70 new members and we expect to train over 200 new members this spring with the help of current fraternity KUDOS CORNER— and sorority members who have assisted in revamping the program, facilitating the small groups and Congratulations to our providing their talent during the dramatic portion of the program. -

Inter-Fraternity Sorority Council Rutgers University-Newark 11/16/2017

Inter-Fraternity Sorority Council Rutgers University-Newark 11/16/2017 1. Calling the Meeting to Order: 5:50 PM 2. Roll Call: Organization Attendance Organization Attendance Alpha Kappa Alpha PRESENT Lambda Theta Phi PRESENT Alpha Phi Alpha PRESENT Lambda Upsilon Lambda PRESENT Chi Upsilon Sigma PRESENT Mu Sigma Upsilon PRESENT Delta Epsilon Psi PRESENT Omega Phi Beta PRESENT Delta Phi Omega PRESENT Omega Phi Chi PRESENT Delta Sigma Theta EXCUSED Phi Iota Alpha ABSENT Iota Nu Delta PRESENT Sigma Beta Rho PRESENT Kappa Alpha Psi PRESENT Sigma Iota Alpha ABSENT Kappa Phi Gamma PRESENT Sigma Lambda Beta PRESENT Kappa Psi Epsilon PRESENT Sigma Lambda Upsilon EXCUSED Lambda Sigma Upsilon PRESENT Tau Kappa Epsilon PRESENT 3. Approval of Minutes 4. Janique’s Report: a. New Member Workshop i. Wednesday, December 13th, free period ii. Mandatory, PRCC 226 iii. Send Janique necessary information about new members on roster b. Take advantage of community service opportunities sent by Janique c. Re-Activation of Phi Beta Sigma i. Issue: Membership 5. President Report: a. Meet the Greeks at the beginning of the semester (inside) pros and cons and Meet the Greeks at the end of the semester (outside) pros and cons i. Inside/Beginning of semester: 1. Pros: No rain date, better view, good rush tactic (6 organizations participate in rush), revenue 2. Cons: Less capacity ii. Outside/End of semester: Inter-Fraternity Sorority Council Rutgers University-Newark 11/16/2017 1. Pros: Greater audience, more capacity, larger space, new members can participate and attend 2. Cons: Rain date b. Alternatives to Meet the Greeks - Greek Swap, Stroll for a cause, Yard Show, Yard Takeover/etc. -

Fraternities & Sororities

Guide to Fraternities & Sororities 2011-2012 GreetinGs from Fraternity & sorority Affairs! Welcome to the university of Rochester Fraternity and Sorority community! Whether you are a fraternity/sorority member, a prospective member, a parent, faculty or staff member, student, or a guest of the university, we are happy to welcome and introduce you to the unique, and award-winning, community of fraternities/sororities in the College. The uR fraternity/sorority system is aligned with the educational philosophy of the College. due to the intentional connection to the academic mission of the College, the organizations appreciate the value of being a part of a learning community. We support a framework that assumes fraternities and sororities can and want to be successful and that the College’s role is to expect and to provide support for their success. The system stresses the importance of autonomy of action within a framework of shared systems, goals, and objectives (expectations for excellence). We believe our success-driven model represents a unique and effective model for the university of Rochester. We are proud of the success achieved by both our chapters and individual members. Annually uR chapters and members are recognized with top national awards for their excellence in scholarship, leadership, programming, service, and risk management. Many members of our fraternity/sorority community are also leaders of a variety of organizations on campus including, but not limited to, Student Government, Class Councils, cultural groups, and academic undergraduate councils. We are fortunate to have many faculty and staff, including thed ean of Students, the dean of Freshmen, and the dean of Admissions and Financial Aid, involved as Chapter Advocates who volunteer to assist organizations in planning and implementing their expectations for excellence and related programs. -

RPHC Scholarship Report Spring 2006

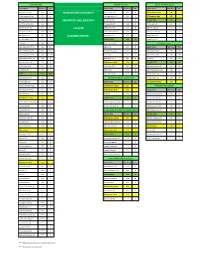

Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey Office of Fraternity and Sorority Affairs RPHC Grades for: Spring 2006 Amy Vojta, Asst. Dean (732) 932-7692 Initiated Members New Members Total Chapter Rank Chapter GPA Rank Chapter GPA Rank Chapter 1 Sigma Lambda Gamma 3.2640 1 Sigma Iota Alpha 3.1880 1 Sigma Lambda Gamma 2 Lambda Upsilon Lambda 3.2080 2 Omega Phi Chi 3.1110 2 Lambda Upsilon Lambda 3 Sigma Lambda Upsilon 3.1170 All Women's Average 3.0480 All Women's Average All Women's Average 3.0480 3 Sigma Beta Rho 2.9810 3 Sigma Lambda Upsilon 4 alpha Kappa Delta Phi 3.0460 All Greek Average 2.9750 4 Sigma Iota Alpha 5 Sigma Beta Rho 3.0280 All Men's Average 2.8750 5 Omega Phi Chi 6 Lambda Theta Phi 3.0000 All RPHC Sorority Average 2.7750 6 Sigma Beta Rho Sigma Gamma Rho 3.0000 All RPPHC Fraternity Average 2.7450 7 Lambda Theta Phi All Greek Average 2.9750 4 Sigma Lambda Upsilon 2.7310 Sigma Gamma Rho 8 Omega Phi Chi 2.9520 5 Pi Delta Psi 2.6420 9 alpha Kappa Delta Phi 9 Kappa Phi Lambda 2.9480 6 Zeta Phi Beta 2.3970 All Greek Average All Men's Average 2.8750 7 Kappa Phi Lambda 2.3120 All Men's Average 10 Pi Delta Psi 2.8270 8 Chi Upsilon Sigma 2.0810 10 Kappa Phi Lambda All RPHC Sorority Average 2.7750 9 alpha Kappa Delta Phi 2.0000 11 Pi Delta Psi 11 Chi Upsilon Sigma 2.7500 10 Omega Psi Phi 1.9370 All RPHC Sorority Average All RPHC Fraternity Average 2.7450 11 Lambda Theta Alpha 1.8750 All RPHC Fraternity Average 12 Lambda Theta Alpha 2.6850 12 Lambda Sigma Upsilon 1.5420 12 Chi Upsilon Sigma 13 Omega Psi Phi 2.6290 13 Mu Sigma Upsilon 1.5000 13 Zeta Phi Beta 14 Zeta Phi Beta 2.5930 Lambda Theta Phi 14 Lambda Theta Alpha 15 Lambda Sigma Upsilon 2.5330 Lambda Upsilon Lambda 15 Lambda Sigma Upsilon 16 Sigma Iota Alpha 2.4750 Omega Phi Beta 16 Omega Psi Phi 17 Mu Sigma Upsilon 2.3750 Sigma Gamma Rho 17 Sigma Lambda Beta 18 Sigma Lambda Beta 2.2220 Sigma Lambda Beta 18 Omega Phi Beta 19 Omega Phi Beta 2.0640 Sigma Lambda Gamma 19 Mu Sigma Upsilon % No New Members Office of Fraternity and Sorority Affairs Amy Vojta, Asst. -

History of Latino Fraternal Movement and Why It Matters on Campus Today Oliver Fajardo, Lambda Theta Phi Fraternity, Inc

History of Latino Fraternal Movement and Why it Matters on Campus Today Oliver Fajardo, Lambda Theta Phi Fraternity, Inc. Latin@s have been attending colleges and universities in the United States since the late 1700s. The first known international Latin American student to enroll in a U.S. university was Francisco de Miranda when he attended Yale in 1784 (Bevis & Lucas, 2007). Throughout the 1800s, more students from Latin America enrolled in U.S. colleges as compared to Latin@s born in the United States. An example of increased native Latin American enrollment was the University of California – Berkeley that had twelve students from Latin America enrolled in their Fifth Class Program compared to four Latin@s born in California in the 1871-1872 academic school year (Register, 1871). In the late 19th century, a demand in skilled workers for Latin America’s new railroads, waterworks, highways, dams, and canals led to increased enrollment of international students in American colleges (Bevis & Lucas, 2007). These international Latin American students began to congregate and create clubs, societies, and fraternities that brought them together (Fajardo, 2015). The first wave of Latin American fraternities began when international students at Cornell founded Alpha Zeta Fraternity during the 1889-1890 academic year (Alpha Chapter, 1890). Alpha Zeta Fraternity started a movement of organizations that catered to international Latin American students that lasted until the spring of 1975 (Fajardo, 2015). Over a dozen fraternities were founded from California to New York and Kansas to Louisiana. These organizations had several reasons for their existence. Some served as political organizations that wanted to liberate Puerto Rico from the United States, others wanted to unite Latin American countries so that they could stand up to perceived U.S. -

1 La Familia: Thoughts on Latinx Interfraternalism Keith D. Garcia

La Familia: Thoughts on Latinx Interfraternalism Keith D. Garcia | University of Minnesota | @kgarcia_sa It does not take long for research on Latinx fraternal organizations (LFOs) to reveal a level of commonality. Beyond a connection to ethnic identity, many LFOs were founded with the intent of creating unity amongst Latinx people. It’s found in their names, visions, missions and purposes. The following examples, with rough translations, exhibit this concept. Lambda Theta Phi Latin Fraternity, Inc.’s motto is “En la unión está la fuerza” (In unity there is strength) while Lambda Sigma Upsilon Latino Fraternity, Inc.’s letters stand for “Latinos Siempre Unidos” (Latinos Always United). You find it in La Unidad Latina, Lambda Upsilon Lambda Fraternity, Inc.’s motto, “La Unidad Para Siempre” (Unity Forever) and several Latina sororities’ names also espouse this value including Sigma Lambda Upsilon/Señoritas Latinas Unidas Sorority, Inc. (Latina Women United), Lambda Pi Upsilon Sorority, Latinas Poderosas Unidas, Inc. (Empowered Latinas United), and Latinas Promoviendo Comunidad/Lambda Pi Chi Sorority, Inc. (Latinas Promoting Community). One of the oldest LFOs, Phi Iota Alpha Fraternity, Inc., was founded upon and continues to espouse the virtues of Pan-Americanism, the idea that countries in Latin America should be unified. The concept of unity is enshrined in the mission of the National Association of Latino Fraternal Organizations (NALFO) which states “NALFO exists to unite and empower its Latino organizations and their communities through advocacy, cultural awareness, and organizational development while fostering positive inter fraternal relationships and collaborating on issues of mutual interest.” While the concept of unity is ever present within the Latinx fraternal community, it has often been narrow in its application. -

Greek Life Brochure

Typical Reasons Students Join a Fraternity/Sorority Joining a fraternity/sorority is just one choice that SUNY Cortland provides to its undergraduate students. We invite everyone to learn more about Greek life on our campus by reviewing this information as well as that found on SUNY • Belief in the values of the organization Cortland’s Fraternities and Sororities website. As of June 2021, 10.8% of our undergraduates belong to a recognized • Leadership, community service, networking and social opportunities fraternity or sorority. • Place to belong and be accepted for who you are http://www2.cortland.edu/offices/campus-activities/fraternities-and-sororities.dot Membership Eligibility Requirements When First Joining; Eligibility verifications are conducted through SUNY Cortland’s Campus Activities Office. • Must be a full-time SUNY Cortland student and cannot be on either Academic Warning or Academic Probation University Recognition is coordinated through the Campus Activities and Corey Union Office. It is limited to organizations with • First semester first year students cannot join any fraternity or sorority official ties to a national fraternity or sorority with the exception of Nu Sigma Chi Sorority which has been grandfathered in. • Returning/continuing students must have earned credit for completing at least 12 credit hours at SUNY Cortland and Recognition validates the fraternity/sorority and gives it permission to operate at SUNY Cortland with the following benefits: have at least a 2.0 cumulative GPA (College does honor/go by higher organizational GPA requirements; Many require • Ability to recruit new members with the cooperation and support of the university; at least a 2.50 cumulative GPA). -

Grade-Report-Fall-2020.Pdf

Community Grades Interfraternity Council National Pan-Hellenic Council Chapter Name Term G.P.A. Size Chapter Name Term G.P.A. Size Chapter Name Term G.P.A. Size Alpha Epsilon Phi (S) 3.80 133 BINGHAMTON UNIVERSITY Alpha Epsilon Pi (F) 3.67 48 All Binghamton Female 3.47 Phi Delta Epsilon (Co-Ed) 3.76 39 Tau Kappa Epsilon (F) 3.53 6 All Binghamton Male 3.28 Delta Sigma Pi (Co-Ed) 3.75 50 FRATERNITY AND SORORITY Zeta Beta Tau (F) 3.51 37 COUNCIL TOTAL 2.79 14 Mu Phi Epsilon (Co-Ed) 3.73 7 Pi Kappa Alpha (F) 3.44 63 Phi Beta Sigma (F) 2.70 4 Sigma Omicron Pi (S) 3.71 15 Fall 2020 Delta Epsilon Psi (F) 3.41 22 Alpha Phi Alpha (F) ***** 3 Sigma Delta Tau (S) 3.69 134 Lambda Phi Epsilon (F) 3.40 4 Delta Sigma Theta (S) ***** 3 Alpha Epsilon Pi (F) 3.67 48 ACADEMIC REPORT Phi Kappa Psi (F) 3.39 67 Kappa Alpha Psi (F) ***** 3 Phi Alpha Delta (Co-Ed) 3.65 39 COUNCIL TOTAL 3.39 528 Omega Psi Phi (F) ***** 1 Phi Mu (S) 3.64 128 Alpha Sigma Phi (F) 3.35 35 Panhellenic Council alpha Kappa Delta Phi (S) 3.63 20 Sigma Chi (F) 3.35 72 Chapter Name Term G.P.A. Size Alpha Omega Epsilon (S) 3.62 38 Tau Alpha Upsilon (F) 3.32 42 Alpha Epsilon Phi (S) 3.80 133 Kappa Kappa Gamma (S) 3.60 124 Zeta Psi (F) 3.32 53 Sigma Delta Tau (S) 3.69 134 Sigma Alpha Epsilon Pi (S) 3.58 44 Delta Sigma Phi (F) 3.32 53 Phi Mu (S) 3.64 128 Kappa Phi Lambda (S) 3.58 22 All Binghamton Male 3.28 COUNCIL TOTAL 3.64 822 Delta Phi Epsilon (S) 3.57 135 Theta Delta Chi (F) 3.27 12 Kappa Kappa Gamma (S) 3.60 124 Nu Alpha Phi (F) 3.55 13 Theta Chi (F) 3.13 8 Sigma Alpha Epsilon Pi (S) 3.58 44 ALL FSL 3.53 1854 Sigma Beta Rho (F) 2.95 6 Delta Phi Epsilon (S) 3.57 135 Tau Kappa Epsilon (F) 3.53 6 Multicultural Greek and Fraternal Council Phi Sigma Sigma (S) 3.52 124 Phi Sigma Sigma (S) 3.52 124 Chapter Name Term G.P.A. -

Chapter Status (Spring 2021)

CURRENT BINGHAMTON UNIVERSITY RECOGNIZED FRATERNITIES & SORORITIES Spring 2021 αΚΔΦ—ALPHA KAPPA DELTA PHI (S) NAPA MALIK (F) MGFC ΒΧΘ − BETA CHI THETA (F) NAPA ΛΘΑ—LAMBDA THETA ALPHA (S) MGFC ΚΦΛ—KAPPA PHI LAMBDA (S) NAPA ΛΣΨ – LAMBDA SIGMA UPSILON (F) MGFC ΝΑΦ—NU ALPHA PHI (F) NAPA ΑΦΑ – ALPHA PHI ALPHA (F) NPHC ΣΟΠ—SIGMA OMICRON PI (S) NAPA ΔΣΘ − DELTA SIGMA THETA (S) NPHC ΣΨΖ—SIGMA PSI ZETA (S) NAPA ΩΨΦ – OMEGA PSI PHI (F) NPHC ΑΕΠ—ALPHA EPSILON PI (F) IFC ΦΒΣ—PHI BETA SIGMA (F) NPHC ΔΣΦ—DELTA SIGMA PHI (F) IFC ΚΑΨ—KAPPA ALPHA PSI (F) NPHC ΖΨ—ZETA PSI (F) IFC ΑΕΦ—ALPHA EPSILON PHI (S) PC ΘΧ—THETA CHI (F) IFC ΔΦΕ—DELTA PHI EPSILON (S) PC ΔΕΨ—DELTA EPSILON PSI (F) IFC ΚΚΓ – KAPPA KAPPA GAMMA (S) PC ΘΔΧ—THETA DELTA CHI (F) IFC ΦΜ —PHI MU (S) PC ΛΦΕ—LAMBDA PHI EPSILON (F) IFC ΣΑΕΠ—SIGMA ALPHA EPSILON PI (S) PC ΣΧ – SIGMA CHI (F) IFC ΣΔΤ—SIGMA DELTA TAU (S) PC ΠΚΑ—PI KAPPA ALPHA (F) IFC ΦΣΣ—PHI SIGMA SIGMA (S) PC ΣΒΡ—SIGMA BETA RHO (F) IFC ΑΚΨ—ALPHA KAPPA PSI (C) PFC ΤΑΥ—TAU ALPHA UPSILON (F) IFC ΑΦΩ—ALPHA PHI OMEGA (C) PFC ΖΒΤ—ZETA BETA TAU (F) IFC ΑΩΕ—ALPHA OMEGA EPSILON (S) PFC ΤΚΕ—TAU KAPPA EPSILON (F) IFC ΔΣΠ—DELTA SIGMA PI (C) PFC ΦΚΨ—PHI KAPPA PSI (F) IFC ΜΦΕ —MU PHI EPSILON (C) PFC ΑΣΦ—ALPHA SIGMA PHI (F) IFC ΘΤ—THETA TAU (F) PFC ΛΠΥ – LAMBDA PI UPSILON (S) NALFO ΦΑΔ—PHI ALPHA DELTA (C) PFC ΛΥΛ—LAMBDA UPSILON LAMBDA (F) NALFO ΦΔΕ—PHI DELTA EPSILON (C) PFC ΛΑΥ—LAMBDA ALPHA UPSILON (F) NALFO ΦΧΘ − PHI CHI THETA (C) PFC ΣΛΥ − SIGMA LAMBDA UPSILON (S) NALFO ΠΣΕ − PI SIGMA EPSILON (C) PFC ΩΦΒ − OMEGA PHI BETA (S) NALFO ΧΨΣ – CHI UPSILON SIGMA (S) NALFO ΣΙΑ – SIGMA IOTA ALPHA (S) NALFO DISCIPLINARY STATUS ΘΧ − THETA CHI (F) Disciplinary Probation Through May 2021 (Hazing) – Additional Sanctions from National Organization – SIGMA CHI (F) Social Suspension through December 2021.