History of Latino Fraternal Movement and Why It Matters on Campus Today Oliver Fajardo, Lambda Theta Phi Fraternity, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Unidad Latina, Lambda Upsilon Lambda Fraternity, Inc

La Unidad Latina, Lambda Upsilon Lambda Fraternity, Inc. Alpha Xi Chapter- Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana Foreword Below are the standard operating procedures by which the Iota Chapter of La Unidad Latina, Lambda Upsilon Lambda Fraternity, Incorporated shall abide. These procedures shall be used along with the Chapter Management Manual, National Constitution, Hermano Protocol, Caballero Protocol, National Pledge Manual, and university policies and procedures as the means of operating the chapter. The responsibilities and obligations provided are the minimum for chapter operation. All other obligations discussed, appointed, or committed to, throughout the year, are also binding. Executive Officer Obligations I. President The President shall be responsible for, but not limited to, coordinating and ensuring the following: 1. Providing a detailed report at all chapter meetings. 2. Implementation of all Iota Chapter annual programs. ( SEE APPENDIX A ) 3. Being the primary contact of communication between the National Council, the Office of Fraternity and Sorority Affairs, etc. 4. Completion and submission of the OFSA Annual Report. ( SEE APPENDIX Q ) 5. Reviewing the annual report requirements at the beginning of his term and ensuring that the chapter meets ALL CRITERIA for ALL eight sections including ALL awards criteria. 6. Creating and Submitting OR delegating, all awards applications for qualifying Hermanos and events, for recognition in the Greek Awards and Latino Student Council Awards. 7. Submitting a completed semester packet and compliance report to the National Council. 8. Create the agenda or each chapter meeting 9. The success of all chapter events. 10. Chapter Contracts Signed by all undergraduates. (Executive Board Obligations Contracts, Financial Dues Agreement) 11. -

FALL 2020 ACADEMIC REPORT Comprehensive University Statistics - Fall 2020 TOTAL COUNT SEMESTER GPA

FALL 2020 ACADEMIC REPORT Comprehensive University Statistics - Fall 2020 TOTAL COUNT SEMESTER GPA ALL UNIVERSITY UnDergraDuate 32,617 3.02 Greek 5,142 3.22 FEMALE UnDergraDuate 15,779 3.17 Greek Female 3,042 3.38 MALE UnDergraDuate 16,775 2.88 Greek Male 2,100 2.96 TOTAL COUNCIL POPULATION IFC 1,991 2.959 MGC 257 3.238 NPHC 30 2.980 CPH 2,864 3.383 NEW & ACTIVE MEMBER GPA BASED ON COUNCIL IFC Active 1,499 2.989 IFC New Member 492 2.874 MGC Active 209 3.233 MGC New Member 47 3.260 NPHC Active 30 2.980 NPHC New Member N/A N/A CPH Active 1,868 3.322 CPH New Member 996 3.417 GRADE SUPERLATIVES TOTAL PERCENT Number of 4.0 GPAs for Semester 1,048 20.38% IFC 199 9.99% MGC 53 20.62% NPHC 2 6.67% CPH 794 27.72% Cumulative 4.0s 481 3 Comprehensive Academic Community Report - Fall 2020 Overall Overall Chapter Total Active New Semester Greater Less Change Rank Rank Fall Council CHAPTER NAME GPA Members Members Members 4.0 than 3.0 Than from Fall 1 6 MGC Alpha Sigma Rho Sorority, Inc. 3.697 19 15 4 8 17 1 0.416 2 1 CPH Kappa Alpha Theta 3.567 161 161 80 88 213 6 0.109 3 2 CPH Pi Beta Phi 3.530 171 171 81 83 219 6 0.077 4 23 MGC Delta Phi Omega Sorority, Inc. 3.520 36 26 10 12 28 5 0.449 5 24 MGC Gamma Alpha Omega Sorority, Inc. -

Lambda Upsilon Lambda Lambda Upsilon Lamb- Da Has Made Its Way Back to OLLU

ISIS Atttack on Brussels “The Lake Front” tries to understand the war on ter- rorism. pg. 1 New Workout: The Dab The newwork out craze has proven to work. pg. 8 La Fraternidad’s Resurgence: Lambda Upsilon Lambda Lambda Upsilon Lamb- da has made its way back to OLLU. pg. 11 your staff THE LAKE FRONT March 2016 Our Lady of the Lake University Volume 62 Issue 3 Opinion PAULINE FIELDS Editor-In-Chief ANGELA CLARK ISIS Attack On Brussels Co-Editor By: Ramses Tejeda case placed inside the train was naco said that “they are sophis- Stateside, both parties used On March 22 at 8 a.m. Brus- timed to explode. ticated and coordinated terror political rhetoric to gain ground JC WOLLSLAGER sels time in Zaventem Airport Belgium has become a mourn- attacks.” with constituencies. Republican Graphic Designer at there was an explosion. Ten ing ground; many people are This brings the question, what presidential candidates, Donald people were confirm dead and confused and shocked about are we doing that isn’t enough? Trump and Ted Cruz used the RICKY SALDANA about 100 people where wound- the whole ordeal. The Belgium How many more people will Belgium terrorist attack to tar- Head Reporter ed. A second attack happen at prime minister urged the com- need to die before we can finally get Muslims with travel bans and Maelbeek metro station at 9:11 munity not to hold rallies in case say we will stop this? surveillance programs. Demo- a.m. About 20 people were killed of any other potential bombings. -

Timeline of Fraternities and Sororities at Texas Tech

Timeline of Fraternities and Sororities at Texas Tech 1923 • On February 10th, Texas Technological College was founded. 1924 • On June 27th, the Board of Directors voted not to allow Greek-lettered organizations on campus. 1925 • Texas Technological College opened its doors. The college consisted of six buildings, and 914 students enrolled. 1926 • Las Chaparritas was the first women’s club on campus and functioned to unite girls of a common interest through association and engaging in social activities. • Sans Souci – another women’s social club – was founded. 1927 • The first master’s degree was offered at Texas Technological College. 1928 • On November 21st, the College Club was founded. 1929 • The Centaur Club was founded and was the first Men’s social club on the campus whose members were all college students. • In October, The Silver Key Fraternity was organized. • In October, the Wranglers fraternity was founded. 1930 • The “Matador Song” was adopted as the school song. • Student organizations had risen to 54 in number – about 1 for every 37 students. o There were three categories of student organizations: . Devoted to academic pursuits, and/or achievements, and career development • Ex. Aggie Club, Pre-Med, and Engineering Club . Special interest organizations • Ex. Debate Club and the East Texas Club . Social Clubs • Las Camaradas was organized. • In the spring, Las Vivarachas club was organized. • On March 2nd, DFD was founded at Texas Technological College. It was the only social organization on the campus with a name and meaning known only to its members. • On March 3rd, The Inter-Club Council was founded, which ultimately divided into the Men’s Inter-Club Council and the Women’s Inter-Club Council. -

Fall 2013 Scholarship Report

Fall 2013 Scholarship Report All Sorority and Fraternity Chapter Averages Rank/Chapter Number of Members GPA 1. Delta Sigma Theta 41 3.18 2. Lambda Theta Alpha 5 3.18 3. Chi Omega 87 3.16 4. Alpha Omicron Pi 112 3.15 5. Alpha Delta Pi 109 3.15 6. Alpha Chi Omega 97 3.04 All Sorority Women 724 3.04 7. Alpha Kappa Alpha 89 2.97 8. Phi Mu Alpha 43 2.96 All Greek Student 1,185 2.90 9. Alpha Phi Alpha 8 2.89 10. Zeta Tau Alpha 86 2.89 11. Alpha Gamma Rho 28 2.89 All University Women 10,417 2.88 12. Sigma Pi 40 2.85 13. Kappa Delta 98 2.82 14. Phi Delta Theta 43 2.80 All University Student 19,763 2.80 15. Sigma Chi 51 2.70 All University Men 9,346 2.77 All Fraternity Men 461 2.66 16. Sigma Nu 55 2.60 17. Alpha Tau Omega 43 2.58 18. Phi Beta Sigma 9 2.57 19. Kappa Sigma 53 2.55 20. Kappa Alpha Order 33 2.42 21. Omega Psi Phi 11 2.38 22. Sigma Phi Epsilon 13 2.37 23. Pi Kappa Phi 31 2.36 Fall 2013 Scholarship Report Fraternity Chapter Averages (Active and New Members) Rank/Chapter Number of Members GPA 1. Phi Mu Alpha 43 2.96 2. Alpha Phi Alpha 8 2.89 3. Alpha Gamma Rho 28 2.89 4. Sigma Pi 40 2.85 5. Phi Delta Theta 43 2.80 6. -

GREEK LIFE GRADE REPORT Fall 2019

GREEK LIFE GRADE REPORT Fall 2019 Office of Greek Life Student Center, Office 104 F, G and H SUMMARY CHAPTER REPORT GPAs are calculated on active membership of organizations (identified on organization’s rosters submitted to the Office of Greek Life) and includes any new members brought into the organization recorded at the end of Fall 2019 semester. COMPARISON BREAKDOWN Cumulative GPAs Only GPAs are calculated on active membership of organizations (identified on organization’s rosters submitted to the Office of Greek Life) and includes any new members brought into the organization recorded at the end of Fall 2019 semester. ** Indicates that the chapter has 3 or less members at the end of the semester and therefore grades are kept private to the public ** CHAPTER REPORT ORGANIZATION Fall 19 GPA Cumulative GPA Alpha Chi Rho 3.301 3.276 Alpha Iota Chi 3.123 3.213 Alpha Kappa Alpha 3.043 3.242 Alpha Phi Alpha *** *** Alpha Phi Delta 2.889 3.02 Alpha Phi Omega 3.474 3.457 Alpha Sigma Rho (Colony) 3.283 3.283 Chi Upsilon Sigma 2.977 2.89 Delta Chi 3.156 3.176 Delta Phi Epsilon 3.405 3.345 Delta Sigma Iota *** *** Delta Xi Delta 3.237 3.308 Iota Phi Theta *** *** Kappa Sigma 3.414 3.359 Lambda Sigma Upsilon 2.828 2.926 Lambda Tau Omega 2.834 2.973 Lambda Theta Alpha 3.018 3.206 Lambda Theta Phi *** *** Lambda Upsilon Lambda 2.854 2.993 Mu Sigma Upsilon 2.103 2.899 Omega Phi Chi 2.904 3.085 Omega Psi Phi *** *** Phi Beta Sigma *** *** Phi Alpha Psi Senate *** *** Phi Delta Theta (Colony) 3.472 3.41 Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia 3.382 3.349 Phi Sigma -

Spring 2016 Office of Fraternity and Sorority Life Scholarship Report

SPRING 2016 OFFICE OF FRATERNITY AND SORORITY LIFE SCHOLARSHIP REPORT Active Member New Member IFC Active Members New Members Organization Totals* Organization GPA GPA GPA 1 Phi Gamma Delta (FIJI) 70 3.219 10 2.668 80 3.148 2 Sigma Phi Epsilon 86 3.120 18 3.052 104 3.110 3 Alpha Delta Phi 45 3.105 2 3.430 54 3.052 4 Zeta Beta Tau 123 3.098 12 2.265 136 3.026 5 Phi Kappa Tau 121 3.021 -- -- 121 3.021 6 Delta Chi 46 3.036 8 3.124 57 3.016 7 Delta Tau Delta 117 3.012 13 2.656 117 3.012 8 Pi Kappa Phi 126 3.044 12 2.621 138 3.009 9 Theta Chi 156 3.082 15 2.499 195 3.001 10 Pi Kappa Alpha 196 3.039 20 2.860 238 2.991 11 Alpha Epsilon Pi 103 3.004 13 2.807 116 2.984 12 Beta Theta Pi 98 2.963 4 2.989 102 2.964 13 Alpha Tau Omega 159 3.010 14 2.387 173 2.963 14 Sigma Pi 77 3.007 10 2.758 91 2.961 15 Kappa Alpha 139 2.927 11 2.438 150 2.894 16 Sigma Alpha Epsilon 80 2.930 13 2.604 93 2.886 17 Phi Delta Theta 124 2.943 16 2.373 140 2.883 18 Tau Kappa Epsilon 67 2.853 -- -- 70 2.868 19 Phi Kappa Psi 50 2.895 8 2.984 73 2.859 20 Chi Phi 133 2.811 -- -- 139 2.807 21 Phi Sigma Kappa 116 2.827 8 2.295 124 2.794 22 Kappa Sigma 117 2.760 11 3.006 130 2.788 Grand Totals 2336 2.987 218 2.688 2641 2.954 Active Member New Member MGC Active Members New Members Organization Totals* Organization GPA GPA GPA 1 Lambda Theta Phi 6 3.292 *** *** 7 3.378 2 alpha Kappa Delta Phi 11 3.299 2 2.964 16 3.130 3 Sigma Lambda Beta 8 2.924 4 3.385 12 3.090 4 Theta Nu Xi 11 2.974 -- -- 11 2.974 5 Phi Iota Alpha 23 2.958 -- -- 23 2.958 6 Sigma Iota Alpha 10 2.782 4 3.244 14 -

Understanding the Experiences of Students in Latino/Latina Fraternities and Sororities

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Emanuel Magaña for the degree of Master of Science in College Student Services Administration presented on April 27, 2012. Title: Understanding the Experiences of Students in Latino/Latina Fraternities and Sororities. Abstract Approved: Mamta Accapadi The purpose of this is study is to investigate the experiences of students in Latino/Latina fraternities and sororities. Five students were selected to take part of the study and were interviewed using a qualitative case study methodology grounded in critical race theory. Five themes were identified: the support system that Latino Greek Lettered Organizations (LGLO) offer, going Greek, challenges, differences from other Greeks, and shifting identify of the organizations from Latino to multicultural. Student affairs practitioners, educators, and researchers will be able to use the findings from this study to better support LGLO’s and conseQuently the success of Latino students on college campuses. © Copyright by Emanuel Magaña April 27, 2012 All Rights Reserved Understanding the Experiences of Students in Latino/Latina Fraternities and Sororities by Emanuel Magaña A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the reQuirements for the degree of Master of Science Presented April 27, 2012 Commencement June 2012 Master of Science thesis of Emanuel Magaña presented on April 27, 2012. APPROVED: Major Professor, representing College Student Services Administration Dean of the College of Education Dean of the Graduate School I understand that my thesis will become part of the permanent collection of Oregon State University libraries. My signature below authorizes release of my thesis to any reader upon reQuest. Emanuel Magaña, Author Acknowledgments - I would first and foremost like to thank my advisor and my committee for providing the guidance I needed to in order to conduct this study. -

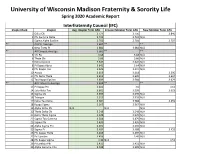

Spring 2020 Community Grade Report

University of Wisconsin Madison Fraternity & Sorority Life Spring 2020 Academic Report Interfraternity Council (IFC) Chapter Rank Chapter Avg. Chapter Term GPA Initiated Member Term GPA New Member Term GPA 1 Delta Chi 3.777 3.756 3.846 2 Phi Gamma Delta 3.732 3.732 N/A 3 Sigma Alpha Epsilon 3.703 3.704 3.707 ** All FSL Average 3.687 ** ** 4 Beta Theta Pi 3.681 3.682 N/A ** All Campus Average 3.681 ** ** 5 Chi Psi 3.68 3.68 N/A 6 Theta Chi 3.66 3.66 N/A 7 Delta Upsilon 3.647 3.647 N/A 8 Pi Kappa Alpha 3.642 3.64 N/A 9 Phi Kappa Tau 3.629 3.637 N/A 10 Acacia 3.613 3.618 3.596 11 Phi Delta Theta 3.612 3.609 3.624 12 Tau Kappa Epsilon 3.609 3.584 3.679 ** All Fraternity Average 3.604 ** ** 13 Pi Kappa Phi 3.601 3.6 3.61 14 Zeta Beta Tau 3.601 3.599 3.623 15 Sigma Chi 3.599 3.599 N/A 16 Triangle 3.593 3.593 N/A 17 Delta Tau Delta 3.581 3.588 3.459 18 Kappa Sigma 3.567 3.567 N/A 19 Alpha Delta Phi N/A N/A N/A 20 Theta Delta Chi 3.548 3.548 N/A 21 Delta Theta Sigma 3.528 3.529 N/A 22 Sigma Tau Gamma 3.504 3.479 N/A 23 Sigma Phi 3.495 3.495 N/A 24 Alpha Sigma Phi 3.492 3.492 N/A 25 Sigma Pi 3.484 3.488 3.452 26 Phi Kappa Theta 3.468 3.469 N/A 27 Psi Upsilon 3.456 3.49 N/A 28 Phi Kappa Sigma 3.44 N/A 3.51 29 Pi Lambda Phi 3.431 3.431 N/A 30 Alpha Gamma Rho 3.408 3.389 N/A Multicultural Greek Council (MGC) Chapter Rank Chapter Chapter Term GPA Initiated Member Term GPA New Member Term GPA 1 Lambda Theta Alpha Latin Sorority, Inc. -

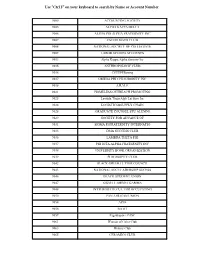

02- Department Code Listing

Use "Ctrl F" on your keyboard to search by Name or Account Number 9000 ACCOUNTING SOCIETY 9005 ALPHA KAPPA DELTA 9006 ALPHA PHI ALPHA FRATERNITY INC 9007 CSUDH MATH CLUB 9008 NATIONAL SOCIETY OF COLLEGIATE 9009 LABOR STUDIES STUDENTS 9013 Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority Inc 9015 ANTHROPOLOGY CLUB 9016 CSUDH Boxing 9017 OMEGA PHI CHI SORORITY INC 9018 A.R.M.S. 9021 HOMELESS OUTREACH PROMOTING 9023 Lambda Theta Alph Lat Soro Inc 9024 LOGISTICS&SUPPLY CHAIN 9028 GRADUATE COUNSEL STU ALUMNI 9029 SOCIETY FOR ADVANCE OF 9031 SIGMA PI FRATERNITY INTERNATIO 9033 DMA SUCCESS CLUB 9036 LAMBDA THETA PHI 9037 PHI IOTA ALPHA FRATERNITY INC 9038 UNIVERSITY BOOK ORGANIZATION 9039 PHILOSOPHY CLUB 9042 BLACK GREEK LETTER COUNCIL 9043 NATIONAL SOC LEADERSHIP SUCESS 9046 BLACK STUDENT UNION 9047 SIGMA LAMBDA GAMMA 9048 INTTERGRATE CUL THR OCCUPATING 9050 PAN AFRICAN UNION 9054 APSS 9056 Pre OT 9059 Pagsikapan - PASC 9061 Women of Color Club 9063 History Club 9065 CERAMICS CLUB 9066 Graduate Society of Public Adm 9068 Native America Indian Associat 9069 Sigma Gamma Rho 9071 Child Development Club 9072 F.L.O.W 9073 International Student Club 9074 Red Print Design Firm 9077 C.O.R.E. 9078 T.W.I.C. 9079 Christians on Campus 9080 CIRCLE K CLUB 9081 Associated Political Science S 9082 Ecology Club 9088 C.O.R.E. Club 9089 Farm Club 9101 CDC 9106 Political Science Students 9118 DH ANIME 9119 Kappa Delta Chi Sorority Inc 9128 ESPIRITU DE NUESTRO FUTURO 9148 GRADUATE ASSOC SOCIAL WORKERS90 9151 HEALTH SCIENCE STUDENT ALLIANC90 9152 HERMANAS UNIDAS 9155 HISPANIC BUSINESS ASSOCIATION 9168 HUMAN RESOURCES MGMT ASSOC 9174 INTER VARSITY CHRISTIAN FELLOW 9175 INTERNATIONAL STUDENT CLUB 9177 TOROS CHRISTIAN FELLOWSHIP 9183 LATINO STUDENT BUSINESS ASSOC 9195 MARKETING CLUB 9200 M.E.CH.A. -

Lehigh University Fraternity and Sorority Community Spring 2018 Grade Report

Lehigh University Fraternity and Sorority Community Spring 2018 Grade Report Note: New Member Grades are included in the Overall Chapter Term Average Interfraternity Council Overall IFC Number of New Member Fraternities Overall Chapter Number of "+/-" from Fraternity New Member New Grades Term Average Members Fall 2017 Ranking Term Average Members Ranking Alpha Epsilon Pi 3.33 45 0.03 1 3.19 13 1 All Greek 3.22 Alpha Tau Omega 3.16 53 0.08 2 2.92 8 6 Psi Upsilon 3.16 51 0.06 2 3.14 16 3 Phi Kappa Theta 3.14 45 0.09 4 2.69 6 12 Theta Chi 3.14 62 0 4 3.00 13 5 Delta Upsilon 3.13 55 -0.03 6 2.83 11 9 Sigma Phi Epsilon 3.12 64 -0.01 7 2.9 11 7 Phi Delta Theta 3.10 52 0.07 8 3.08 13 4 Chi Phi 3.05 54 0.08 9 2.57 11 13 All Fraternity 3.05 Phi Sigma Kappa 3.04 43 -0.02 10 3.19 8 1 Theta Xi 2.95 55 0.11 11 2.73 14 11 Delta Chi 2.92 45 -0.12 12 2.52 16 14 Chi Psi 2.84 60 -0.04 13 2.78 15 10 Kappa Alpha 2.79 62 -0.01 14 2.9 21 7 Average/Total 53.29 0.0207143 12.57 If under 5 list as (≤5) * Grades are not reported for chapters who have only one member per FERPA Lehigh University Fraternity and Sorority Community Spring 2018 Grade Report Cultural Greek Council Overall CGC Number of New Member CGC Sororities Overall Chapter Number of "+/-" from Sorority New Member New Grades Term Average Members Fall 2017 Ranking Term Average Members Ranking All Sorority 3.38 All Greek 3.22 Mu Sigma Upsilon 3.00 6 0.25 1 n/a n/a n/a Lambda Theta Alpha 2.56 6 -0.56 2 * 1 1 Average/Total 6.00 (≤5) * Grades are not reported for chapters who have only one member per FERPA -

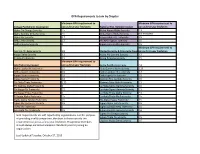

GPA Requirements to Join by Chapter

GPA Requirements to Join by Chapter Minimum GPA requirement to Minimum GPA requirement to College Panhellenic Association join as first-year freshmen National Pan-Hellenic Council join as first-year freshmen Alpha Chi Omega Sorority 2.5 Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority 2.3 Alpha Gamma Delta Sorority 2.5 Delta Sigma Theta Sorority Not Provided Alpha Phi Sorority 2.7 Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity 2.5 Delta Zeta Sorority 2.7 Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity 2.5 Delta Gamma Sorority 3 Sigma Gamma Rho Sorority 2.5 Minimum GPA requirement to Gamma Phi Beta Sorority 3.8 United Sorority & Fraternity Counciljoin as first-year freshmen Kappa Delta Sorority 3.3 Alpha Phi Gamma Sorority 2.3 Pi Beta Phi Sorority 2.5 Alpha Pi Sigma Sorority 2.5 Minimum GPA requirement to Interfraternity Council join as first-year freshmen Alpha Psi Rho Fraternity 2.4 Alpha Epsilon Pi Fraternity 2.5 Beta Gamma Nu Fraternity 2.25 Delta Upsilon Fraternity 2.5 Delta Lambda Phi Fraternity 2.7 Kappa Alpha Fraternity 2.9 Delta Sigma Psi Sorority 2.5 Kappa Sigma Fraternity 2.6 Gamma Rho Lambda Sorority 2.5 Phi Delta Theta Fraternity 2.75 Gamma Zeta Alpha Fraternity 2.5 Phi Gamma Delta Fraternity 3 Lambda Sigma Gamma Sorority 2.5 Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity 2.5 Lambda Sigma Gamma Sorority 2.5 Phi Kappa Theta Fraternity 3 Lambda Theta Alpha Sorority 2.6 Pi Kappa Alpha Fraternity 2.5 Lambda Theta Phi Fraternity 2.5 Sigma Alpha Epsilon Fraternity 2.5 Nu Alpha Kappa Fraternity 2.5 Sigma Phi Epsilon Fraternity 3.5 Sigma Alpha Zeta Sorority 2.5 Theta Chi Fraternity 3 Sigma Lambda Beta Fraternity 2.5 Zeta Beta Tau Fraternity 2.5 Sigma Lambda Gamma Sorority 2.6 2 GPA requirements are self-reported by organizations.