I N D U S T R I a L S U B L I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finding Aid for the John Sloan Manuscript Collection

John Sloan Manuscript Collection A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum The John Sloan Manuscript Collection is made possible in part through funding of the Henry Luce Foundation, Inc., 1998 Acquisition Information Gift of Helen Farr Sloan, 1978 Extent 238 linear feet Access Restrictions Unrestricted Processed Sarena Deglin and Eileen Myer Sklar, 2002 Contact Information Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives Delaware Art Museum 2301 Kentmere Parkway Wilmington, DE 19806 (302) 571-9590 [email protected] Preferred Citation John Sloan Manuscript Collection, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum Related Materials Letters from John Sloan to Will and Selma Shuster, undated and 1921-1947 1 Table of Contents Chronology of John Sloan Scope and Contents Note Organization of the Collection Description of the Collection Chronology of John Sloan 1871 Born in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania on August 2nd to James Dixon and Henrietta Ireland Sloan. 1876 Family moved to Germantown, later to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 1884 Attended Philadelphia's Central High School where he was classmates with William Glackens and Albert C. Barnes. 1887 April: Left high school to work at Porter and Coates, dealer in books and fine prints. 1888 Taught himself to etch with The Etcher's Handbook by Philip Gilbert Hamerton. 1890 Began work for A. Edward Newton designing novelties, calendars, etc. Joined night freehand drawing class at the Spring Garden Institute. First painting, Self Portrait. 1891 Left Newton and began work as a free-lance artist doing novelties, advertisements, lettering certificates and diplomas. 1892 Began work in the art department of the Philadelphia Inquirer. -

(212) 792-0300 [email protected]

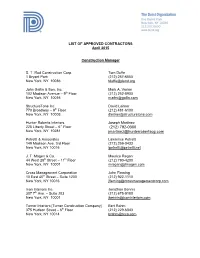

LIST OF APPROVED CONTRACTORS April 2015 Construction Manager S. T. Rud Construction Corp. Tom Duffe 1 Bryant Park (212) 257-6550 New York, NY 10036 [email protected] John Gallin & Son, Inc. Mark A. Varian 102 Madison Avenue – 9th Floor (212) 252-8900 New York, NY 10016 [email protected] StructureTone Inc. David Leitner 770 Broadway – 9th Floor (212) 481-6100 New York, NY 10003 [email protected] Hunter Roberts Interiors Joseph Martinez 225 Liberty Street – 6th Floor (212) 792-0300 New York, NY 10281 [email protected] Petretti & Associates Lawrence Petretti 149 Madison Ave, 3rd Floor (212) 259-0433 New York, NY 10016 [email protected] J. T. Magen & Co. Maurice Regan 44 West 28th Street – 11th Floor (212) 790-4200 New York, NY 10001 [email protected] Cross Management Corporation John Fleming 10 East 40th Street – Suite 1200 (212) 922-1110 New York, NY 10016 [email protected] Icon Interiors Inc. Jonathan Bennis 307 7th Ave. – Suite 203 (212) 675-9180 New York, NY 10001 [email protected] Turner Interiors [Turner Construction Company] Bert Rahm 375 Hudson Street – 6th Floor (212) 229-6043 New York, NY 10014 [email protected] James E. Fitzgerald, Inc. John Fitzgerald 252 West 38th Street, 10th Floor (212) 930-3030 New York, NY 10018 [email protected] Clune Construction Company Tommy Dwyer The Chrysler Center (646) 569-3220 405 Lexington Avenue – 27th Floor [email protected] New York, NY 10174 Electrical Contractors Schlesinger Electrical Contractors, Inc. Alan Burczyk 664 Bergen St. (718) 636-3944 Brooklyn, NY 11238 [email protected] Star Delta Electric LLC Randy D’Amico 17 Battery Pl #203 (212) 943-5527 New York, NY 10004 [email protected] Fred Geller Electrical, Inc. -

(312) 443-3625 [email protected] [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 14, 2013 MEDIA CONTACTS: Erin Hogan Chai Lee (312) 443-3664 (312) 443-3625 [email protected] [email protected] THE ART INSTITUTE HONORS 100-YEAR RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PICASSO AND CHICAGO WITH LANDMARK MUSEUM–WIDE CELEBRATION First Large-Scale Picasso Exhibition Presented by the Art Institute in 30 Years Commemorates Centennial Anniversary of the Armory Show Picasso and Chicago on View Exclusively at the Art Institute February 20–May 12, 2013 Special Loans, Installations throughout Museum, and Programs Enhance Presentation This winter, the Art Institute of Chicago celebrates the unique relationship between Chicago and one of the preeminent artists of the 20th century—Pablo Picasso—with special presentations, singular paintings on loan from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and programs throughout the museum befitting the artist’s unparalleled range and influence. The centerpiece of this celebration is the major exhibition Picasso and Chicago, on view from February 20 through May 12, 2013 in the Art Institute’s Regenstein Hall, which features more than 250 works selected from the museum’s own exceptional holdings and from private collections throughout Chicago. Representing Picasso’s innovations in nearly every media—paintings, sculpture, prints, drawings, and ceramics—the works not only tell the story of Picasso’s artistic development but also the city’s great interest in and support for the artist since the Armory Show of 1913, a signal event in the history of modern art. BMO Harris is the Lead Corporate Sponsor of Picasso and Chicago. "As Lead Corporate Sponsor of Picasso and Chicago, and a bank deeply rooted in the Chicago community, we're pleased to support an exhibition highlighting the historic works of such a monumental artist while showcasing the artistic influence of the great city of Chicago," said Judy Rice, SVP Community Affairs & Government Relations, BMO Harris Bank. -

Exhibition of the Arthur Jerome Eddy Collection of Modern Paintings and Sculpture Source: Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago (1907-1951), Vol

The Art Institute of Chicago Exhibition of the Arthur Jerome Eddy Collection of Modern Paintings and Sculpture Source: Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago (1907-1951), Vol. 25, No. 9, Part II (Dec., 1931), pp. 1-31 Published by: The Art Institute of Chicago Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4103685 Accessed: 05-03-2019 18:14 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The Art Institute of Chicago is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago (1907-1951) This content downloaded from 198.40.29.65 on Tue, 05 Mar 2019 18:14:34 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms EXHIBITION OF THE ARTHUR JEROME EDDY COLLECTION OF MODERN PAINTINGS AND SCULPTURE ARTHUR JEROME EDDY BY RODIN THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO DECEMBER 22, 1931, TO JANUARY 17, 1932 Part II of The Bulletin of The Art Institute of Chicago, Volume XXV, No. 9, December, 1931 This content downloaded from 198.40.29.65 on Tue, 05 Mar 2019 18:14:34 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms No. 19. -

The Development of Art Education in America 1900-1918

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Plan B Papers Student Theses & Publications 7-30-1964 The Development of Art Education in America 1900-1918 Jerry Josserand Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/plan_b Recommended Citation Josserand, Jerry, "The Development of Art Education in America 1900-1918" (1964). Plan B Papers. 398. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/plan_b/398 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Plan B Papers by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DEVELOPMENT OF ART EDUCATION IN AMERICA 1900-1918 (TITLE) BY Jerry Josserand PLAN B PAPER SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN EDUCATION AND PREPARED IN COURSE Art 591 IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY, CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS 1964 YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS PLAN B PAPER BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE DEGREE, M.S. IN ED. This paper was written for Art 591 the summer of 1961. It is the result of historical research in the field of art education. Each student in the class covered an assigned number of years in the development of art education in America. The paper was a section of a booklet composed by the class to cover this field from 1750 up to 1961. The outline form followed in the paper was develpped and required in its writing by the instructor. THE DEVELOPMENT OF ART EDUCATION IN AMERICA 1900-1918 Jerry Josserand I. -

Annual Procurement Report Fiscal Year 2016 – 2017

Andrew M. Cuomo, Governor RuthAnne Visnauskas, Commissioner/CEO Annual Procurement Report Fiscal Year 2016 – 2017 For the Period Commencing November 1, 2016 and Ending October 31, 20171 January 25, 2018 NEW YORK STATE HOUSING FINANCE AGENCY STATE OF NEW YORK MORTGAGE AGENCY NEW YORK STATE AFFORDABLE HOUSING CORPORATION STATE OF NEW YORK MUNICIPAL BOND BANK AGENCY TOBACCO SETTLEMENT FINANCING CORPORATION 641 Lexington Avenue Ι New York, NY 10022 212-688-4000 Ι www.nyshcr.org 1 Although AHC’s fiscal year runs from April 1st through March 31st, for purposes of this consolidated Report, AHC’s procurement activity is reported using a November 1, 2016 – October 31, 2017 period, which conforms to the fiscal period shared by four of the five Agencies. NEW YORK STATE HOUSING FINANCE AGENCY STATE OF NEW YORK MORTGAGE AGENCY NEW YORK STATE AFFORDABLE HOUSING CORPORATION STATE OF NEW YORK MUNICIPAL BOND BANK AGENCY TOBACCO SETTLEMENT FINANCING CORPORATION Annual Procurement Report For the Period Commencing November 1, 2016 and Ending October 31, 2017 Annual Procurement Report Index SECTION TAB Agencies’ Listing of Pre-qualified Panels…………………………..……………………………….1 Summary of the Agencies’ Procurement Activities………………………………………..………. 2 Agencies’ Consolidated Procurement and Contract Guidelines (Effective as of December 15, 2005, Revised as of September 12, 2013)…………………………………....3 Explanation of the Agencies’ Procurement and Contract Guidelines………………………………4 TAB 1 Agencies’ Listing of Pre-qualified Panels TAB 1 Agencies’ Listing of Pre-Qualified Panels Arbitrage Rebate Services Pre-qualified Panel of the: ▸ New York State Housing Finance Agency - BLX Group LLC - Hawkins, Delafield & Wood LLP - Omnicap Group LLC ▸ State of New York Mortgage Agency ▸ State of New York Municipal Bond Bank Agency ▸ Tobacco Settlement Financing Corporation - Hawkins, Delafield & Wood LLP Appraisal and Market Study Consultant Pre-qualified Panel of the: ▸ New York State Housing Finance Agency - Capital Appraisal Services, Inc. -

Scottsdale Art Auction Seeking Consignments for April 6 Western Art Sale SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ

THE GALLERY • THE GALLERY • THE GALLERY • THE GALLERY ANTIQUES AND THE ARTS WEEKLY ț 5 CHURCH HILL RD ț BOX 5503 ț NEWTOWN, CONNECTICUT, 06470 ț FALL 2018 2 — THE GALLERY October 12, 2018 — Antiques and The Arts Weekly THE GALLERY • THE GALLERY • THE GALLERY • THE GALLERY • THE GALLERY • THE GALLERY • THE GALLERY • THE GALLERY Tel. 203-426-8036 or 203-426-3141 or Fax 203-426-1394 www.AntiquesAndTheArts.com contact: Barb Ruscoe email - [email protected] Published by The Bee Publishing Company, Box 5503, Newtown Connecticut 06470 New Acquisitions & Brimming Fair Schedule Propel Edward T. Pollack Fine Arts BRUNSWICK, MAINE — Edward T. 1,” “Nudo 2” and “Nudo 3”; prints by Ynez Pollack Fine Arts has a busy fall and winter Johnston, Jacques Hnizdovsky; several im- season planned for 2018–19. Following a portant Whistler lithographs; and a brilliant successful show at the Brooklyn Book and example of the now rare exhibition poster Print Fair at the Brooklyn Expo in Green- for the famous 1985 exhibition of paintings point early September, Ed Pollack will by Warhol and Basquiat. exhibit at the New York Satellite Print Fair Recent sales have included books illus- at Mercantile Annex 37. The show is held trated and signed by Thomas Hart Benton October 25–28, the same dates as the In- and Keith Haring, a lithograph by Yasuo ternational Fine Print Dealers Association’s Kuniyoshi, several woodcuts by Carol Fine Art Print Fair, in a venue very close Summers, two watercolor drawings by the to the Javits Center. During January and Monhegan Island painter Lynne Drexler, an February, the firm participates in print fairs early and rare Stow Wengenroth lithograph in Portland, Ore., Los Angeles/Pasadena and of Eastport, Maine, a lithograph by Robert San Francisco/Berkeley, Calif. -

Oral History Interview with John Davis Hatch, 1964 June 8

Oral history interview with John Davis Hatch, 1964 June 8 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview JH: John Davis Hatch WW: H. Wade White WW: Mr. Hatch, I understand that you were appointed director of the first district, the New England states, for the Federal Art Project from its beginning, and we hope very much that you can give us your reminiscences of the project and how it developed under your directorship. JH: Thank you, Mr. White. I'll do what I can. First of all, I think we have to go back and say that it was Region I, which is the New England states of the Public Works of Art Project. My connection with it, and all the government art projects, except for later work in connection with murals in post offices in competitions of that kind, and stopping in at the headquarters in Washington under both Mr. Bruce and Mr. Cahill, was entirely with the Public Works of Art Project. This was only of short duration and then we later broke it up into states and under states it became the Federal Art Projects - WPA, I think, actually was the title of it. WW: What did that stand for? JH: Works Progress Administration. Thus - it became a part of a bureaucratic set-up. Earlier under PWAP it was completely artist inspired. The beginning of this project, as you probably know, was that Edward Bruce, who had been a banker in the Philippines and had made plenty of wherewithal, had retired. -

A Stellar Century of Cultivating Culture

COVERFEATURE THE PAAMPROVINCETOWN ART ASSOCIATION AND MUSEUM 2014 A Stellar Century of Cultivating Culture By Christopher Busa Certainly it is impossible to capture in a few pages a century of creative activity, with all the long hours in the studio, caught between doubt and decision, that hundreds of artists of the area have devoted to making art, but we can isolate some crucial directions, key figures, and salient issues that motivate artists to make art. We can also show why Provincetown has been sought out by so many of the nation’s notable artists, performers, and writers as a gathering place for creative activity. At the center of this activity, the Provincetown Art Associ- ation, before it became an accredited museum, orga- nized the solitary efforts of artists in their studios to share their work with an appreciative pub- lic, offering the dynamic back-and-forth that pushes achievement into social validation. Without this audience, artists suffer from lack of recognition. Perhaps personal stories are the best way to describe PAAM’s immense contribution, since people have always been the true life source of this iconic institution. 40 PROVINCETOWNARTS 2014 ABOVE: (LEFT) PAAM IN 2014 PHOTO BY JAMES ZIMMERMAN, (righT) PAA IN 1950 PHOTO BY GEORGE YATER OPPOSITE PAGE: (LEFT) LUCY L’ENGLE (1889–1978) AND AGNES WEINRICH (1873–1946), 1933 MODERN EXHIBITION CATALOGUE COVER (PAA), 8.5 BY 5.5 INCHES PAAM ARCHIVES (righT) CHARLES W. HAwtHORNE (1872–1930), THE ARTIST’S PALEttE GIFT OF ANTOINETTE SCUDDER The Armory Show, introducing Modernism to America, ignited an angry dialogue between conservatives and Modernists. -

STARRETT-LEHIGH BUILDING, 601-625 West 26Th Street, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission October 7, 1986; Designation List 186 LP-1295 STARRETT-LEHIGH BUILDING, 601-625 west 26th Street, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1930-31; Russell G. and Walter M. Cory, architects; Yasuo Matsui, associate architect; Purdy & Henderson, consulting engineers. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 672, Lot 1. On April 13, 1982, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Starrett-Lehigh Building, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 20). The hearing was continued to June 8, 1982 (Item No. 3). Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Four witnesses spoke in favor of designation, and a letter supporting designation was read into the record. Two representatives of the owner spoke at the hearings and took no position regarding the proposed designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Starrett-Lehigh Building, constructed in 1930-31 by architects Russell G. and walter M. Cory with Yasuo Matsui as associate architect and Purdy & Henderson as consulting engineers, is an enormous warehouse building that occupies the entire block bounded by West 26th and 27th Streets and 11th and 12th Avenues. A cooperative venture of the Starrett Investing Corporation and the Lehigh Valley Railroad, and built by Starrett Brothers & Eken, the structure served originally as a freight terminal for the railroad with rental manufacturing and warehouse space above. A structurally complex feat of engineering with an innovative interior arrangement, the Starrett-Lehigh Building is also notable for its exterior design of horizontal ribbon windows alternating with brick and concrete spandrels. -

A Finding Aid to the Edward Bruce Papers, 1902-1960(Bulk 1932-1942), in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Edward Bruce Papers, 1902-1960(bulk 1932-1942), in the Archives of American Art Erin Corley Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. July 20, 2006 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1904-1938..................................................... 5 Series 2: Correspondence, circa 1921-1957............................................................ 6 Series 3: Writings, circa 1931-1942...................................................................... -

Download Lesson

GRADE LEVEL Architecture that Pops! 3-5 Create a pop-up paper building inspired by the cityscapes of Colin Campbell Cooper. STANDARDS MATERIALS VISUAL ART Domain: Create o Paper 9 x 12 VA.Cr1.A o Scrap Paper VA.Cr1.B o Scissors VA.Cr2.A o Crayons, Markers, etc. VA.Cr2.B o VA.Cr2.C Glue VA.Cr3.A INSTRUCTIONS 1. 1. Cut one 9 x 12 piece of drawing or construction paper in half. 2. Using one piece of the paper, fold in half lengthwise. 3. From the folded edge of the paper, cut two identical lines about 2. an inch long and an inch and a half apart. 4. Open the paper and push the cut tab to the inside of the page, folding along the creased line to make it stay. 5. Using scrap paper, create background images for the city 3. (skyscrapers, trees, etc.). Color and cut them out then glue them to either side of the pop-up tab. 6. Create a pop-up building using scrap paper. The building can be anything you choose but make sure it is slightly wider than the 4. pop-up tab. Color it then cut it out. 7. Glue the building onto the bottom half of the pop-up tab. 8. Add any additional design elements you like! 9. Finally, glue your second piece of paper around the outside of the card to conceal the cut paper. DISCUSSION About the artist: Colin Campbell Cooper was an American Impressionist best known for his cityscapes. He was born in Philadelphia in 1856 and died in California in 1937.