Oral History Interview with John Davis Hatch, 1964 June 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Finding Aid to the Edward Bruce Papers, 1902-1960(Bulk 1932-1942), in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Edward Bruce Papers, 1902-1960(bulk 1932-1942), in the Archives of American Art Erin Corley Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. July 20, 2006 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1904-1938..................................................... 5 Series 2: Correspondence, circa 1921-1957............................................................ 6 Series 3: Writings, circa 1931-1942...................................................................... -

Down from the Ivory Tower: American Artists During the Depression

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1982 Down from the ivory tower: American artists during the Depression Susan M. Eltscher College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Eltscher, Susan M., "Down from the ivory tower: American artists during the Depression" (1982). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625189. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-a5rw-c429 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOWN FROM THE IVORY TOWER: , 4 ‘ AMERICAN ARTISTS DURING THE DEPRESSION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Susan M. Eltscher APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts ^jiuu>0ur> H i- fc- bbcJ^U i Author Approved, December 1982 Richard B. Sherman t/QOJUK^r Cam Walker ~~V> Q ' " 9"' Philip J/ Fuiyigiello J DEDICATION / ( \ This work is dedicated, with love and appreciation, to Louis R. Eltscher III, Carolyn S. Eltscher, and Judith R. Eltscher. ( TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACRONYMS................... .......................... v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.......................................... -

The Public Works of Art Project in Minnesota, 1933-34

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 1989 Joint Venture or Testy Alliance?: The Public Works of Art Project in Minnesota, 1933-34 Thomas O'Sullivan Minnesota Historical Society Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons O'Sullivan, Thomas, "Joint Venture or Testy Alliance?: The Public Works of Art Project in Minnesota, 1933-34" (1989). Great Plains Quarterly. 405. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/405 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. JOINT VENTURE OR TESTY ALLIANCE? THE PUBLIC WORKS OF ART PROJECT IN MINNESOTA, 1933,34 THOMAS O'SULLIVAN Like many American painters of his genera approved, we were to develop larger and more tion, Syd Fossum left art school under the cloud complete paintings from them. of the Great Depression. The economic uncer tainties of the 1930s only added to the dubious • • • support a young painter in the Midwest might The directions seemed vague, but Mac and expect. But an unimagined opportunity launched I busily dashed off about half a dozen sketches Fossum and many others into unparalleled pro apiece. To make sure that they were truly ductivity as artists and self-respect as involved "American Scene," we included in our members of the art community and American paintings, plenty ofNRA symbols with their society. -

Recorder of Deeds Building

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking “x” in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter “N/A” for “not applicable.” For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Recorder of Deeds Building other names 2. Location street & number 515 D Street NW not for publication city or town Washington, DC vicinity state DC code DC County code 001 zip code 20001 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant nationally statewide locally. ( See continuation sheet for additional comments). -

Dr. VP Franklin, Chairperson Dr. Molly Mcgarry Dr

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE African Americans and the Spanish-American War and Philippine Insurrection: Military Participation, Recognition, and Memory, 1898-1904 Doctor of Philosophy in History by Timothy Dale Russell June 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. V.P. Franklin, Chairperson Dr. Molly McGarry Dr. Rebecca Kugel Copyright by Timothy Dale Russell 2013 The Dissertation of Timothy Dale Russell is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Dr. V. P. Franklin, without whose direction and invaluable assistance this dissertation would not have been possible. Thank you for providing the wisdom, patience, and expertise that guided me through this endeavor. I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Rebecca Kugel and Dr. Molly McGarry, for their mentorship and support through the years. I would like to thank my loving wife Vera, my parents Mike and Betty Russell, and Peter and Sheila Woodington, for their constant support and encouragement as I labored through the dissertation process. Thank you for providing the foundation and stability that kept me buoyed and focused on achieving this goal. I would also like to offer my heartfelt appreciation to Lance Eisenhauer, Jon Ille, and Dr. Owen Jones, who were always ready to lend a welcome ear and offer kind advice. Thank you for your friendship, I will cherish it always. Finally, I wish to take a moment to remember those dear family members who I have lost in the past year, and whose influence I will carry with me always. My grandparents, Ezra and Bettie Ellis, whose example and life lessons taught me the meaning of facing and overcoming life’s challenges, thank you. -

List of Exhibitions Held at the Corcoran Gallery of Art from 1897 to 2014

National Gallery of Art, Washington February 14, 2018 Corcoran Gallery of Art Exhibition List 1897 – 2014 The National Gallery of Art assumed stewardship of a world-renowned collection of paintings, sculpture, decorative arts, prints, drawings, and photographs with the closing of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in late 2014. Many works from the Corcoran’s collection featured prominently in exhibitions held at that museum over its long history. To facilitate research on those and other objects included in Corcoran exhibitions, following is a list of all special exhibitions held at the Corcoran from 1897 until its closing in 2014. Exhibitions for which a catalog was produced are noted. Many catalogs may be found in the National Gallery of Art Library (nga.gov/research/library.html), the libraries at the George Washington University (library.gwu.edu/), or in the Corcoran Archives, now housed at the George Washington University (library.gwu.edu/scrc/corcoran-archives). Other materials documenting many of these exhibitions are also housed in the Corcoran Archives. Exhibition of Tapestries Belonging to Mr. Charles M. Ffoulke, of Washington, DC December 14, 1897 A catalog of the exhibition was produced. AIA Loan Exhibition April 11–28, 1898 A catalog of the exhibition was produced. Annual Exhibition of the Work by the Students of the Corcoran School of Art May 31–June 5, 1899 Exhibition of Paintings by the Artists of Washington, Held under the Auspices of a Committee of Ladies, of Which Mrs. John B. Henderson Was Chairman May 4–21, 1900 Annual Exhibition of the Work by the Students of the CorCoran SChool of Art May 30–June 4, 1900 Fifth Annual Exhibition of the Washington Water Color Club November 12–December 6, 1900 A catalog of the exhibition was produced. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form IWT

NPS Form 10-900-b 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) ?* RECEJVEO 2280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form IWT. REGISTER Of HIS WIONALPARK This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing _____Arkansas Post Offices with Section Art_______________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts ______Arkansas Post Offices and the Treasury Department's Section of Fine Arts ______Program, 1938-1942_____________________________________ C. Geographical Data State of Arkansas I I See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, i hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements s/rt forth$\ 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. SignaKire of certifying official Date State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this -

Eleanor Roosevelt's Paper

;' Papers of • Anna Ele anor Roosevelt 1884 - 1964 Accession Numbers: MS. 63-1; MS 73-40 The papers of Anna Eleanor Roosevelt were donated by Mrs. Roosevelt and her children. The unpublished writings of Anna Eleanor Roosevelt are in the public domain. Quantity: 1095 l inear feet (approximately 2,190,000 pages) Restrictions: The papers contain material restricted in accordance with Executive Order 12958, and material which might constitute the invasion of privacy of living persons has been. closed. ~ " Related Material: Numerous collections in the Library including: President Frankl in D. Roosevelt's Official, Personal and .5ecrtary' s "~ les; Franklin D. Roosevelt: Papers pertaining to Family, Business ,arid Personal Affairs; Franklin D. Roosevelt: Papers as Vice Presidential Candidate, 1920; Frankli n D. Roosevelt: Papers as Governor of New York, 1929 -1932 ; Eleanor Roosevelt Oral. History project; Papers of Anna Roosevelt Halsted; Papers of Lorena Hickok; and Roosevelt Family Papers Donated by the Children Of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, jo\"" A. , i~H}"".! •. t't, jI (." \... I " \ / Early Family Papers. 1860-1910 and Undated. ./ Container 1 Contains letters, writings, and diaries of Eleanor Roosevelt's parents, Anna Rebecca Hall and Elliott Roosevelt, her grandparents, Mr. and Mrs. V.G. Hall, Jr., cousin Susan Parish, aunt Edith "Pussie" Hall (Mrs. William Forbes Morgan). Correspondents include Anna "Bamie" or "Bye" Roosevelt Cowles and Corinne Roosevelt Robinson, sisters of Elliott Roosevelt; Ella Bulloch and Laura Delano, aunts of Elliott Roosevelt; Elizabeth "Tissie" Hall Mortimer, sister of Anna Hall Roosevelt; W.C.P. Rhodes, clergyman and friend of the Hall family; also, some loose flyleaves from Roosevelt family books. -

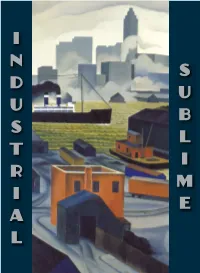

I N D U S T R I a L S U B L I

Art/New York/History Billowing smoke, booming industry, noble bridges, and an epic waterfront are the landscape of a transforming New I York from 1900 to 1940. The convulsive changes in the N metropolis and its rivers are embraced in modern paintings from Robert Henri to Georgia O’Keeffe. D I U S N T S R I D A U L U B s S u L b l T i I m R e M The book is the companion catalogue to the exhibition Industrial Sublime: Modernism and the Transformation of New York’s Rivers, 1900 to 1940. fordham university press hudson river museum I The project is organized by Kirsten M. Jensen and Bartholomew F. Bland. COVER DETAILS E FRONT: George Ault. From Brooklyn Heights, 1925. Collection of the Newark Museum BACK: John Noble. The Building of Tidewater, c.1937, The Noble Maritime Collection; George Parker. East River, N.Y.C., 1939. Collection of the New-York Historical Society; Everett Longley Warner. Peck Slip, N.Y.C., n.d. Collection of the New-York Historical Society; Ernest A Lawson. Hoboken Waterfront, c. 1930. Collection of the Norton Museum of Art A COPUBLICATION OF L Empire State Editions An imprint of Fordham University Press New York www.hrm.org www.fordhampress.com INDUSTRIAL SUBLIME INDUSTRIAL SUBLIME Modernism and the Transformation of New York’s Rivers, 1900-1940 Empire State Editions An imprint of Fordham University Press New York Hudson River Museum www.hrm.org www.fordhampress.com I know it’s unusual for an artist to want to work way up near the roof of a big hotel, in the heart of a roaring city, but I think that’s just what the artist of today needs for stimulus.. -

Book of Bruce; Ancestors and Descendants Of

5,1 !i -^ )arlington Memorial Library ..„i.c.s.iii _ „...,^ tok &3..a..?.i^. ) (r / i i.' X 7 J^^ BOOK OF BRUCE *^m^ -^ 0.Mt iSook of Bruce ANCESTORS AND DESCENDANTS OF liing %ohttt of g)cotlantJ Being an Historical and Genealogical Survey of the Kingly and Noble Scottish House of Bruce and a Full Account of Its Principal Collateral Families. With Special Reference to the Bruces of Clackmannan, Cultmalindie, Caithness, and the Shetland Islands, and Their American Descendants BY LYMAN HORACE WEEKS Author of Prominent Families of New York THE AMERICANA SOCIETY NEW YORK. <\ J \ Copyright, 1907, by THE AMERICANA SOCIETY New YoKic Dedicated to the Memory of daieorge Tsmct whose genius contributed substantially to the advancement in America of "The Art Preservative of All Arts" CONTENTS CON TEN TS TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS, 15 CHAPTER I GENERAL INTRODUCTION AND HISTORICAL SURVEY, . 19 CHAPTER II SCANDINAVIAN ORIGIN, 29 CHAPTER III THE BRUGES IN SCOTLAND, 55 CHAPTER IV KING ROBERT BRUCE, OF SCOTLAND, 75 CHAPTER V BRUGES OF CLACKMANNAN, CULTMALINDIE, AND CAITH- NESS, 91 CHAPTER VI BRUGES OF KINLOSS, ELGIN, AND KINCARDINE, ... 109 9 CONTENTS CHAPTER VII PAGE BRUGES OF AIRTH, 127 CHAPTER VIII THE CAVENDISH-BRUCE FAMILY OF THE DUKES OF DEVONSHIRE, 139 CHAPTER IX ROYAL HOUSE OF STEWART, 153 CHAPTER X LINE OF THE IRISH KINGS, 177 CHAPTER XI ANCIENT ROYAL HOUSE OF SCOTLAND, 191 CHAPTER XII LINE OF THE SAXON KINGS, 209 CHAPTER XIII BRUCE ANCESTRY FROM ROYAL HOUSES OF CONTINEN- TAL EUROPE, 223 CHAPTER XIV COLLATERAL FAMILIES OF SCOTLAND, 247 CHAPTER XV CASTLES AND CHURCHES, 281 10 CONTENTS CHAPTER XVI PAoa ARMS OF BRUGES AND COLLATERAL FAMILIES, .. -

EXH001 IMA Exhibition Records, 1883 – Present | Indianapolis Museum of Art Archives

EXH001 IMA Exhibition Records, 1883 – Present | Indianapolis Museum of Art Archives By Samantha Norling Collection Overview Title: IMA Exhibition Records, 1883 – Present Collection ID: EXH001 Primary Creator: Indianapolis Museum of Art Extent: Arrangement: This collection is arranged alphabetically by creator. Date Acquired: Various Languages: English Scope and Contents of the Materials The IMA Archives Exhibition Records document the planning and execution of exhibitions created by and/or held at the Art Association of Indianapolis, the John Herron Art Institute, and the Indianapolis Museum of Art starting in 1883 and continuing through the present day. This collection is ongoing, as the Indianapolis Museum of Art continues to create new exhibition records each year. Individual exhibition files may include checklists, exhibition catalogs, installation photography, correspondence, press clippings, curatorial research files, shipping, receiving, and lending records, and other documentation. A file and listing have been created for every exhibition, regardless of whether any archival material survives. File listings with "[empty]" indicate that there is no archival material available for the exhibition. Many early exhibitions do not have any surviving archival documentation. This is an ongoing project to process these exhibition records, starting with the earliest records. All available materials have not yet been entered. For a complete searchable list of IMA Exhibitions please visit http://www.imamuseum.org. IMA Archives IMA Exhibition -

Resource Guide

RESOURCE GUIDE 1934: A New Deal for Artists is organized and circulated by the Smithsonian American Art Museum with support from the William R. Kenan Jr. Endowment Fund and the Smithsonian Council for American1 A NEW9 DEAL3 FOR ARTISTS4 Art. The C. F. Foundation in Atlanta supports the museum’s traveling exhibition program, Treasures to Go. May 26 – August 21, 2011 01 “I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people.” FDR, accepting the Democratic Party nomination for President, 1932 Detail: Ilya Bolotowsky (American, 1907-1981). In the Barber Shop, 1934. Oil on Canvas. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor, 1964.1.79 1934: A NEW DEAL FOR ARTISTS TaBLE OF CONTENTS May 26–August 21, 2011 1 Exhibition Introduction 1934: A New Deal for Artists celebrates the 75th anniversary of the Public 2 Public Works of Art Project Works of Art Project by drawing on the Smithsonian American Art 3 Industry Museum’s unparalleled collection of vibrant paintings created for the program. The 56 paintings in the exhibition are a lasting visual record of 4 The City America at a specific moment in time. George Gurney, deputy chief curator, organized the exhibition with Ann Prentice Wagner, independent 5 City Life curator. Federal officials in the 1930s understood how essential art was to 6 Labor sustaining America’s spirit. During the depths of the Great Depression, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s administration created the Public 7 American People Works of Art Project, which lasted only six months from mid-December 1933 to June 1934.