Mobile Money Use in Uganda: a Preliminary Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Finance for Energy Access in Uganda

DIGITAL FINANCE FOR ENERGY ACCESS IN UGANDA: PUTTING MOBILE MONEY BIG DATA ANALYTICS TO WORK Mayank Jain, Robin Gravesteijn, Arne Jacobson, Emily Gamble, Nicola Scarrone ABSTRACT Access to clean energy is a basic need that directly supports people’s livelihood, yet more than 30 million Ugandans live without electricity. Pay-as-you-go (PayGo) is a promising and innovative financing solution that can make clean energy affordable for low-income people. However, there remains significant knowledge gaps regarding the digital energy finance market’s size, outreach, growth and impact. This study leverages anonymized mobile money data of PayGo solar energy users in Uganda to gain insight on digital energy financing in Uganda. It also draws from a customer phone survey that assesses solar product adoption and quality of life improvements. We find that the Uganda solar market is growing rapidly and currently has around one million active customers. Around 12 percent of the Ugandan households own a solar home system and there is opportunity for further market expansion, especially in areas with high levels of mobile money penetration. The clean energy market is becoming more inter-connected with the digital finance market. In fact, digital energy financing through PayGo has promoted wider financial inclusion around 110,000 new mobile money customers. Likewise, when Uganda’s implemented a temporary mobile money tax it caused an immediate slow-down in PayGo uptake and new mobile money activations indicating it negatively impacted the country’s access to clean energy and formal finance. The customer survey result indicates that poorer customers seem equally able to purchase larger solar systems as compared to richer customers because of mobile money financing. -

Public Notice

PUBLIC NOTICE PROVISIONAL LIST OF TAXPAYERS EXEMPTED FROM 6% WITHHOLDING TAX FOR JANUARY – JUNE 2016 Section 119 (5) (f) (ii) of the Income Tax Act, Cap. 340 Uganda Revenue Authority hereby notifies the public that the list of taxpayers below, having satisfactorily fulfilled the requirements for this facility; will be exempted from 6% withholding tax for the period 1st January 2016 to 30th June 2016 PROVISIONAL WITHHOLDING TAX LIST FOR THE PERIOD JANUARY - JUNE 2016 SN TIN TAXPAYER NAME 1 1000380928 3R AGRO INDUSTRIES LIMITED 2 1000049868 3-Z FOUNDATION (U) LTD 3 1000024265 ABC CAPITAL BANK LIMITED 4 1000033223 AFRICA POLYSACK INDUSTRIES LIMITED 5 1000482081 AFRICAN FIELD EPIDEMIOLOGY NETWORK LTD 6 1000134272 AFRICAN FINE COFFEES ASSOCIATION 7 1000034607 AFRICAN QUEEN LIMITED 8 1000025846 APPLIANCE WORLD LIMITED 9 1000317043 BALYA STINT HARDWARE LIMITED 10 1000025663 BANK OF AFRICA - UGANDA LTD 11 1000025701 BANK OF BARODA (U) LIMITED 12 1000028435 BANK OF UGANDA 13 1000027755 BARCLAYS BANK (U) LTD. BAYLOR COLLEGE OF MEDICINE CHILDRENS FOUNDATION 14 1000098610 UGANDA 15 1000026105 BIDCO UGANDA LIMITED 16 1000026050 BOLLORE AFRICA LOGISTICS UGANDA LIMITED 17 1000038228 BRITISH AIRWAYS 18 1000124037 BYANSI FISHERIES LTD 19 1000024548 CENTENARY RURAL DEVELOPMENT BANK LIMITED 20 1000024303 CENTURY BOTTLING CO. LTD. 21 1001017514 CHILDREN AT RISK ACTION NETWORK 22 1000691587 CHIMPANZEE SANCTUARY & WILDLIFE 23 1000028566 CITIBANK UGANDA LIMITED 24 1000026312 CITY OIL (U) LIMITED 25 1000024410 CIVICON LIMITED 26 1000023516 CIVIL AVIATION AUTHORITY -

UIBFS-FINANCIAL-SERVICES-MAGAZINE-Issue-011-2021-Web.Pdf

Financial Services Magazine Finance and Banking BANKING • COMMODITIES • INSURANCE • STOCK MARKETS • MICROFINANCE • TECHNOLOGY • REAL ESTATE AUGUST 2021 /ISSUE 011 , FREE COPY SERVICES MAGAZINE Banking on Innovative Financial Technology to Deliver a Cashless Economy FINANCE & BANKING MICRO FINANCE FINANCIAL NEWS How banks and fintechs are Digitizing financial transactions Artificial intelligence as a key leading Uganda into a cashless in Micro Finance Institutions, driver of the bank of the future. economy post COVID -19. SACCOs to promote efficiency. UGANDA KENYA RWANDA SOUTH SUDAN BURUNDI TANZANIA ISSUE 11 July - August 2021 I Financial Services Magazine Finance and Banking II ISSUE 11 July - August 2021 Financial Services Magazine Finance and Banking CONTENTS 01 How Banks & Fintechs are Leading Uganda into a Cashless Economy Post Covid 19 04 Towards a Cashless Economy in Uganda-A Regulatory Perspective 08 Digital Banking Innovations mean Uganda is On Track to Achieve a Cashless Economy 11 Financial Inclusion & Evolution of Digital Payments In Uganda 12 Artificial intelligence as a key driver of the bank of the future 16 Role of Data Driven Analytics in Business Decision Making 18 Emerging Financial Crimes and Digital Threats to Financial Sector Growth 22 Relevance of Bancassurance to The Customer Today 24 Uganda - Dealing with Cyber security Risk in The Banking and Financial Services Industry: The Need for a New Mindset 27 Housing Finance Bank: Overcoming Challenging Times Through Customer Focus and Dedication 29 Digitizing Financial -

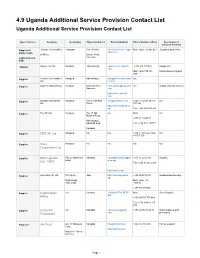

4.9 Uganda Additional Service Provision Contact List Uganda Additional Service Provision Contact List

4.9 Uganda Additional Service Provision Contact List Uganda Additional Service Provision Contact List Type of Service Company Location(s) Physical Address Email & Website Phone Number (office) Description of Services Provided Supplier of Sunrise Commodities Kampala Plot 163/165, Monteirovincent711@y Mob: +256 712 624 624 Suppliers and millers maize, beans, ahoo.com & Millers Bombo Road, maize flour and Kawempe CSB Supplier Aponye (U) Ltd Kampala Nalukolongo aponyeonline@gmail. +256 414 270 526 Supply and com Mob: +256 772 603 transportation of grains 909 Supplier Premier Commodities Kampala Nalukolongo info@premiercommodit n/a Ltd ies.com Supplier Export Trading Group Kampala Industrial Area info.uganda@etgworld. n/a Supply of grains and oils Namanve com http://www.etgworld. com Supplier Byinzika Enterprises Kampala Plot 3, Johnston [email protected] +256 414 259 519/312 n/a Ltd Street, 277 221 http://www.biyinzika.co. ug/ Fax: +256 414 343 268 Supplier Tiny Mirrors Kampala Plot 17 Old n/a Mob: n/a Masaka Road, +256-712-666453 Nalukolongo industrial area, Fax: +256-414-274777 Kampala Supplier SRS (U) Ltd Kampala n/a n/a +256 41 285 282 +256 n/a 41 505 723 Supplier Diary Kampala n/a n/a n/a n/a Corporation Ltd Supplier MTN Uganda Plot 22 Hanninton Kampala customerservice@mt +256 31 221 2333 Supplier Road n.co.ug Ltd - VSAT Fax: +256 31 221 2233 http://mtn.co.ug/ Supplier Agro ways (U) Ltd Plot 34-60 Jinja http://www.agroways. +256 454 479 381 Supplies/warehousing ug/ Kyabazinga Mob: +256 712 Way, Jinja 404245, +256 782 391354 Supplier Capital Reef- n/a Kampala HK@CAPITALREEF. -

Registered Attendees

Registered Attendees Company Name Job Title Country/Region 1996 Graduate Trainee (Aquaculturist) Zambia 1Life MI Manager South Africa 27four Executive South Africa Sales & Marketing: Microsoft 28twelve consulting Technologies United States 2degrees ETL Developer New Zealand SaaS (Software as a Service) 2U Adminstrator South Africa 4 POINT ZERO INVEST HOLDINGS PROJECT MANAGER South Africa 4GIS Chief Data Scientist South Africa Lead - Product Development - Data 4Sight Enablement, BI & Analytics South Africa 4Teck IT Software Developer Botswana 4Teck IT (PTY) LTD Information Technology Consultant Botswana 4TeckIT (pty) Ltd Director of Operations Botswana 8110195216089 System and Data South Africa Analyst Customer Value 9Mobile Management & BI Nigeria Analyst, Customer Value 9mobile Management Nigeria 9mobile Nigeria (formerly Etisalat Specialist, Product Research & Nigeria). Marketing. Nigeria Head of marketing and A and A utilities limited communications Nigeria A3 Remote Monitoring Technologies Research Intern India AAA Consult Analyst Nigeria Aaitt Holdings pvt ltd Business Administrator South Africa Aarix (Pty) Ltd Managing Director South Africa AB Microfinance Bank Business Data Analyst Nigeria ABA DBA Egypt Abc Data Analyst Vietnam ABEO International SAP Consultant Vietnam Ab-inbev Senior Data Analyst South Africa Solution Architect & CTO (Data & ABLNY Technologies AI Products) Turkey Senior Development Engineer - Big ABN AMRO Bank N.V. Data South Africa ABna Conseils Data/Analytics Lead Architect Canada ABS Senior SAP Business One -

Lad Case Study

LAD CASE STUDY Using Private Equity to Improve f Power Distribution in Uganda Chris Walker LAD ABOUT LAD The Leadership Academy for Development (LAD) trains government officials and business leaders from developing countries to help the private sector be a constructive force for economic growth and development. It teaches carefully selected participants how to be effective reform leaders, promoting sound public policies in complex and contentious settings. LAD is a project of the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law, part of Stanford University’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, and is conducted in partnership with the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. LAD gratefully acknowledges support from the Omidyar Network. Using Private Equity to Improve Power Distribution in Uganda Introduction It is summer 2004. Fred Kalisa, the Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Energy sits in his Kampala home on the eve of one of the biggest moments in his political career. Kalisa had dedicated the past ten years of his life to building Uganda’s energy sector and two summers ago he had spearheaded the government’s wide-reaching Energy Reform drive. That effort split the vertically-integrated Ugandan Electricity Board (UEB) into three distinct state-owned companies to manage generation, transmission and distribution, respectively. The next few weeks would likely determine how much that hard work paid off, in what was to potentially be Africa’s first electricity distribution concession granting and privatization. Kalisa knows the stakes are high. After several private companies had pulled out of the negotiations to join the concession, he is left with only one potential partner, a newly formed parastatal organization from London and Johannesburg along with potential support from the World Bank. -

Privacy in Uganda

0 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 ! 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 ! 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 Privacy in Uganda 0 1 1 10 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 An Overview of0 How0 ICT Policies Infringe0 on Online Privacy 0 0 0 0 and Data Protection 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 @ CIPESA ICT Policy Briefing Series No. 06/15 December 2015 0 100110010010 1010110100 100010 010100 110101 001010 01001 001010 00 110101 00101001 001 01010 0010001 000100010100100 1000010 1010010 110101 00101001 001 010 0 110101 00101001 001 01010 0010001 000100010100100 1000010 101001010 010100 110101 00101001 001 0 1101 001001 001010 100110 010010 1010 110100 10010 0101 1101 001001 001010 100110 010010 1010 110100 10010 01010100 001010 10010 11101 001001 001010 100110 010010 1010 110100 10010 01010100 00 110101 00101001 001 01010 0010001 000100010100100 1000010 1010010 110101 001001 001010 110101 00101001 001 01010 0010001 0001000101 Introduction 00 110101 00101001 001 01010 0010001 000100010100100 1000010 101001010100 001001 100010 001010 11010 00 110101 00101001 001 01010 0010001 000100010100100 1000010 1010010 001001 00101001 001 0 001010 10010 11101 001001 001010 100110 010010 1010 110100 10010 0101010010 0010 00 110101 00101001 001 01010 0010001 000100010100100 1000010 1010 10100 1001 100010 0 00 110101 00101001 001 01010 0010001 000100010100100 1000010 1010010 As of June 2015, Uganda had an internet penetration rate of 37% and there were 64 telephone connections per 100 inhabitants.1 This was made possible by increasing investments in the Information Communication Technologies (ICT) sector by the private sector and – to a lesser extent - the government, proliferation of affordable smart phones and a steady decrease in internet costs enabled by a liberal competitive telecommunication sector. -

Global Information Society Watch 2009 Report

GLOBAL INFORMATION SOCIETY WATCH (GISWatch) 2009 is the third in a series of yearly reports critically covering the state of the information society 2009 2009 GLOBAL INFORMATION from the perspectives of civil society organisations across the world. GISWatch has three interrelated goals: SOCIETY WATCH 2009 • Surveying the state of the field of information and communications Y WATCH technology (ICT) policy at the local and global levels Y WATCH Focus on access to online information and knowledge ET ET – advancing human rights and democracy I • Encouraging critical debate I • Strengthening networking and advocacy for a just, inclusive information SOC society. SOC ON ON I I Each year the report focuses on a particular theme. GISWatch 2009 focuses on access to online information and knowledge – advancing human rights and democracy. It includes several thematic reports dealing with key issues in the field, as well as an institutional overview and a reflection on indicators that track access to information and knowledge. There is also an innovative section on visual mapping of global rights and political crises. In addition, 48 country reports analyse the status of access to online information and knowledge in countries as diverse as the Democratic Republic of Congo, GLOBAL INFORMAT Mexico, Switzerland and Kazakhstan, while six regional overviews offer a bird’s GLOBAL INFORMAT eye perspective on regional trends. GISWatch is a joint initiative of the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) and the Humanist Institute for Cooperation with -

Notes to the Financial Statements 34

Secure Online Payments Open your online store to international customers by accepting & payments. Transactions are settled NO FOREX UGX USD in both UGX and USD EXPOSURE Powered by for more Information 0417 719229 [email protected] XpressPay is a registered TradeMark Secure Online Payments 2016 ANNUAL REPORT Open your online store to international customers by accepting & payments. Transactions are settled NO FOREX UGX USD in both UGX and USD EXPOSURE Powered by for more Information 0417 719229 [email protected] XpressPay is a registered TradeMark ENJOY INTEREST OF UP TO 7% P.A. WITH OUR PREMIUM CURRENT ACCOUNT INTEREST IS CALCULATED DAILY AND PAID MONTHLY. CONTENTS Overview About Us 6 Our Branch Network 7 Our Corporate Social Responsibility 8 Corporate Information 11 Governance Chairman’s Statement 12 Managing Director/CEO’s Statement 14 Board of Directors’ Profiles 18 Executive Committee 20 Directors’ Report 21 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 23 Report of the Independent Auditors 24 Orient Bank Limited Annual Report and Consolidated 04 Financial Statements For the year ended 31 December 2016 OVERVIEW GOVERNANCE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Financial Statements Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 26 Bank Statement of Comprehensive Income 27 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 28 Bank Statement of Financial Position 29 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 30 Bank Statement of Changes in Equity 31 Consolidated Statement of Cash flows 32 Bank Statement of Cash flows 33 Notes to the Financial Statements 34 Orient Bank Limited Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements For the year ended 31 December 2016 05 ...Think Possibilities ABOUT US Orient Bank is a leading private sector commercial Bank in Uganda. -

MITI Magazine – Forests and Energy, Issue 47

ISSUE NO.47|JULY - SEPTEMBER 2020 FORESTS AND ENERGY | THE TREE FARMERS MAGAZINE FOR AFRICA| ENERGY IN WOODY BIOMASS UTILIZING TREE BIOMASS: MATHENGE CROTON NUTS HOME-GROWN (PROSOPIS FOR BIOFUEL, AND LOCALLY JULIFLORA) FOR FERTILIZERS AND OWNED ENERGY CHARCOAL FODDER FORESTS AND ENERGYTHE ACACIAS OF AFRICA BRIQUETTE PRODUCTION IN MAFINGA BGF INITIATES THE CERTIFICATION PROCESS FOR THE INTERNATIONAL TIMBER MARKET I ISSUE 47 | JULY - SEPTEMBER 2020 1 | A PUBLICATION OF BETTER GLOBE FORESTRY | FORESTS AND ENERGY Wonders of Dryland Forestry he Schools’ Green Initiative Challenge is The ten-year project is designed as a competition a unique project implemented by KenGen amongst the participating institutions for the highest TFoundation in partnership with Better Globe seedling survival rates through the application of Forestry and Bamburi Cement Ltd. various innovations at the schools’ woodlots. The main objective is the greening of over 460 Currently, there are 500 schools from the three acres in the semi-arid counties of Embu, Kitui counties taking part in the afforestation contest for and Machakos with Mukau (M. volkensii) and the ultimate prize of educational trips, scholarship Muveshi (S. siamea) tree species as a way of opportunities, and other prizes. Plans are underway mitigating climate change and providing wood to add more schools in the coming years. fuel and alternative income opportunities for the local communities. The afforestation competition is in line with the Government of Kenya’s Vision 2030 to achieve Through the setting up of woodlots in participating 10% forest cover across the country. schools, the project acts as a change agent to establish a tree-planting culture for multiple benefits in dry-land areas. -

Uganda at 50: the Past, the Present and the Future

UGANDA AT 50: THE PAST, THE PRESENT AND THE FUTURE A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue Organised by ACODE, 93.3 Kfm and NTV Uganda at the Sheraton Hotel - Kampala – October 3, 2012 Naomi Kabarungi-Wabyona ACODE Policy Dialogue Report Series, No. 17, 2013 UGANDA AT 50: THE PAST, THE PRESENT AND THE FUTURE A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue Organised by ACODE, 93.3 Kfm and NTV Uganda at the Sheraton Hotel - Kampala – October 3, 2012 Naomi Kabarungi-Wabyona ACODE Policy Dialogue Report Series, No. 17, 2013 ii A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue 2012 Published by ACODE P.O. Box 29836, Kampala - UGANDA Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: http://www.acode-u.org Citation: Kabarungi, N. (2013). Uganda at 50: The Past, the Present and the Future. A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue. ACODE Policy Dialogue Report Series, No.17, 2013. Kampala. © ACODE 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior permission of the publisher. ACODE policy work is supported by generous donations from bilateral donors and charitable foundations. The reproduction or use of this publication for academic or charitable purpose or for purposes of informing public policy is exempted from this restriction. ISBN 978 9970 34 009 5 Cover Photo: A Cross section of participants attending the Uganda @50 in 4 Hours Dialogue held on October 3, 2012 at Sheraton Hotel in Kampala. -

Banking Sector Liberalisation in Uganda Process, Results and Policy Options

Banking Sector Liberalisation in Uganda Process, Results and Policy Options Research report Editors: Madhyam & SOMO December 2010 Banking Sector Liberalisation in Uganda Process, Results and Policy Options Research report By: Lawrence Bategeka & Luka Jovita Okumu (Economic Policy Research Centre, Uganda) Editors: Kavaljit Singh (Madhyam), Myriam Vander Stichele (SOMO) December 2010 SOMO is an independent research organisation. In 1973, SOMO was founded to provide civil society organizations with knowledge on the structure and organisation of multinationals by conducting independent research. SOMO has built up considerable expertise in among others the following areas: corporate accountability, financial and trade regulation and the position of developing countries regarding the financial industry and trade agreements. Furthermore, SOMO has built up knowledge of many different business fields by conducting sector studies. 2 Banking Sector Liberalisation in Uganda Process, Results and Policy Options Colophon Banking Sector Liberalisation in Uganda: Process, Results and Policy Options Research report December 2010 Authors: Lawrence Bategeka and Luka Jovita Okumu (EPRC) Editors: Kavaljit Singh (Madhyam) and Myriam Vander Stichele (SOMO) Layout design: Annelies Vlasblom ISBN: 978-90-71284-76-2 Financed by: This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of SOMO and the authors, and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Published by: Stichting Onderzoek Multinationale Ondernemingen Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations Sarphatistraat 30 1018 GL Amsterdam The Netherlands Tel: + 31 (20) 6391291 Fax: + 31 (20) 6391321 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.somo.nl Madhyam 142 Maitri Apartments, Plot No.