Creativity in Car Design – the Behaviour at the Edges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Customer Satisfaction Program 16088 Cylinder Head Gasket Damage

Customer Satisfaction Program 16088 Cylinder Head Gasket Damage Reference Number: N162069400 Release Date: February 2017 Revision: 00 Attention: This program is in effect until March 31, 2019. Model Year Make Model From To RPO Description Buick LaCrosse 2017 2017 LGX 3.6L V-6 DFI Engine Cadillac CT6 2017 2017 LGX 3.6L V-6 DFI Engine Cadillac CTS 2017 2017 LGX 3.6L V-6 DFI Engine Cadillac XT5 2017 2017 LGX 3.6L V-6 DFI Engine Chevrolet Camaro 2017 2017 LGX 3.6L V-6 DFI Engine GMC Acadia 2017 2017 LGX 3.6L V-6 DFI Engine Involved vehicles are marked “open” on the Investigate Vehicle History screen in GM Global Warranty Management system. This site should always be checked to confirm vehicle involvement prior to beginning any required inspections and/or repairs. Condition Certain 2017 model year Buick LaCrosse, Cadillac CT6, CTS, and XT5, Chevrolet Camaro, and GMC Acadia vehicles equipped with a 3.6L LGX engine, may have a condition in which oil is starved to the overhead left side intake camshaft journals and the two #2 cylinder intake valve stationary hydraulic lash adjuster due to the hole not punched thru on the left side cylinder head gasket. The customer may encounter higher than normal noise levels with the potential for severe damage to the timing chain, camshaft and engine. Correction The left side cylinder head gasket will be replaced. The related valve-train parts are to be inspected for damage and replaced if necessary. Parts Transverse Engine Applications Note: Do not replace parts unless damaged Quantity Part Name Part No. -

Bull's Eye Edition 6 2017.Pub

BULL’S-EYE Morris Car Club Of Victoria Official Newsletter November 2017 Morris 1100 feature edition In This Issue This month’s feature article is from Rob Carter who touches on his grandfather’s love of BMC, notably an 1100 and later an 1800 (pictured below). I remember back in the 60s My sister owned a Morris 1100 and while I was swooning around in a Datsun 1600 I used to scoff at her The evolution of BMC “pensioners” car; that was until I small cars in Australia did manage to drive the thing which was a revelation. It was Did you Know? smooth, handled like a go-kart and all with hydrolastic suspen- Events calendar sion. Topping it off was the fact that the thing felt as solid as the proverbial brick out house. Contribute to future So, when Rob’s feature arrived, I started to research the mighty Bull’s-Eye editions 1100 and through my research, Contributions from members are en- decided it may well have ushered couraged. The content should BMC’s rosiest period in Australia. around 400 to 500 words and if pos- sible, have photographs to increase BMC won a car of the year gong appeal and encourage readership. from Wheels Magazine and was an Australian top seller of innova- [email protected] tive, safe, practical and enjoyable or vehicles. Thanks Rob for plant- PO Box 104 Footscray West LPO, ing the seed, even though you may not have intended to do so. So, let’s start where I started; Rob’s contribution. -

A Century of People Cars

Homepage lightauto.com A Century of People Cars A history of the lightweight car and its impact on the progress in personal transport and mobility in Europe and Asia List of Chapters The Revolution in Personal Transport in Europe Origins of the Lightweight Car Early Days 1910 to 1916 Post War Progress 1918 to 1929 Consolidation 1930 to 1939 Rebuilding 1945 to 1955 Diversity 1955 to 1969 Maturity 1970 to 1979 Conformity 1980 to 1989 Sophistication 1990 to 1999 The Revolution in Personal Transport in Europe What is the definition of personal transport? I think it is a means of transport that an individual has at their command at any time to travel were ever they wish. Many forms of transport have been used for that purpose throughout the ages. The horse with or without a carriage or other wheeled vehicle was the most commonly used of various animals to provide a means of transport. The boat in one form or another has been used for the same purpose on water. With the advent of railways their have been private trains, but usually such a conveyance was for heads of state and the fabulously rich.From the beginning of the development of powered flight most forms of aircraft have been used for personal transport by a very small percentage of the population. The entire above has limitations in one form or another, from range of operation, area of use or predominately high cost of ownership and running costs. When introduced the bicycle was a relatively low cost innovation that provided personal transport to a great number of people and still does for millions through out the world. -

Creativity in Car Design – the Behaviour at the Edges

The 2nd International Conference on Design Creativity (ICDC2012) Glasgow, UK, 18th-20th September 2012 CREATIVITY IN CAR DESIGN – THE BEHAVIOUR AT THE EDGES C. Dowlen London South Bank University, UK Abstract: The paper is developed from a longer evaluation of the history of car design. This larger evaluation used statistical processes for investigating the direction of history. Rather than looking at the way that design thinking and paradigms have become established in car design, the paper takes a sideways look at the variations and quirky cars that have been built, categorising them. The paper ends with a brief look at how and why novelty might become innovation and hence alter the course of the product history. This is where the novelty demonstrates significant advantages for the customer and manufacturer. Keywords: automotive design, product history, innovation studies 1. Introduction Cars have been around us since the latter part of the 19th Century. This paper is a sideways offshoot from a more rational and extensive study into the development of design paradigms in car history. It looks at oddball and off-the-wall thinking in car history and firstly, revels in the variety and secondly, asks more serious questions of how the eccentric might become an accepted innovation. 1.1 Being creative doesn‟t sell cars People do not love new ideas, particularly when they might be asked to part with money to purchase novelty. They usually purchase a product to fulfil a need or desire. Products have to work reliably and effectively. Novelty doesn‘t necessarily do that: novel aspects of products need to be tested carefully to ensure they work and they fulfil the expectations. -

Automotive Transmissions

Automotive Transmissions Second Edition Harald Naunheimer · Bernd Bertsche · Joachim Ryborz · Wolfgang Novak Automotive Transmissions Fundamentals, Selection, Design and Application In Collaboration with Peter Fietkau Second Edition With 487 Figures and 85 Tables 123 Dr.-Ing. Harald Naunheimer Professor Dr.-Ing. Bernd Bertsche Vice President Corporate Research Director and Development Universität Stuttgart ZF Friedrichshafen AG Institute of Machine Components Graf-von-Soden-Platz 1 Pfaffenwaldring 9 88046 Friedrichshafen 70569 Stuttgart Germany Germany [email protected] [email protected] Dr.-Ing. Joachim Ryborz Dr.-Ing. Wolfgang Novak Project Manager Development Engineer Development Transmission Daimler AG for Light Commercial Vehicle Mercedesstraße 119 ZF Friedrichshafen AG 70546 Stuttgart Alfred-Colsman-Platz 1 Germany 88045 Friedrichshafen [email protected] Germany [email protected] In Collaboration with Translator Dipl.-Ing. Peter Fietkau Aaron Kuchle Scientific Employee Foreign Language Institute Universität Stuttgart Yeungnam University Institute of Machine Components 214-1 Dae-dong Pfaffenwaldring 9 Gyeongsan, Gyeongbuk 70569 Stuttgart Korea 712-749 Germany [email protected] peter.fi[email protected] ISBN 978-3-642-16213-8 e-ISBN 978-3-642-16214-5 DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-16214-5 Springer Heidelberg Dordrecht London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2010937846 c Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 1994, 2011 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. -

Anniversary Dates 2018

Anniversary dates 2018 Audi Tradition Audi Tradition 2 Anniversary dates 2018 Content Anniversaries in our corporate history January 1938 May 1963 80 years – In memory of Bernd Rosemeyer ..............5 55 years – End of NSU bicycle production ..............14 February 1928 July 1958 90 years – NSU 6/30 hp .........................................6 45 years – End of production of the Prinz 4 ...........15 February 1968 July 1958 50 years – Italdesign .............................................7 60 years – Groundbreaking for a new plant in Ingolstadt .....................................16 February 1993 25 years – Establishment of Audi Hungaria August 1928 Motor Kft. ............................................................8 90 years – NSU 7/34 ............................................17 March 1928 August 1938 90 years – First DKW car ........................................9 80 years – Crash tests at the Central Testing Unit of the Auto Union .........................................18 March 1958 60 years – NSU Prinz ............................................10 August 1978 40 years – Audi 80 B2 ..........................................19 March 1983 35 years – Audi 100 Avant (C3) .............................11 August 1998 20 years – Audi TT Coupé .....................................20 April 1958 60 years – Takeover of Auto Union GmbH September 1953 by Daimler Benz AG .............................................12 65 years – Three-cylinder DKW F 91 ......................21 May 1933 September 1963 85 years – Audi Front ...........................................13 -

Engines Exposed Engines Exposed Exhibit Map There Are More Than 60 on View, but Here Matt Anderson, Curator of Check out More Autos with Their Hoods Popped

Take it forward.® 1926 Rolls-Royce 1963 Buick Riviera 1965 Goldenrod New Phantom Limousine Into Autos? Keep pace with the latest content, collections and expert insights for collectors, gearheads, race fans and restorers. Cruise into thehenryford.org/onwheels 1933 Willys Drag Racer or subscribe to OnWheels at thehenryford.org/enews. We’ve popped the hoods on the incredible stories of grit and imagi- nation that drive us forward. Dozens of our most fascinating mod- els share the inside story of this evolving technology. Discover the Mark Your Calendar For thinking behind our most advanced cars that started over a century ago. Dive into the surprising and daring history of the automobile on These Popular Car Shows a deeper level. Daily Programming Saturday Programming Exploring Automotive Innovations Make Something: Saturdays Join us for a 20-minute conversation about January 14-February 26 10:00-3:00 our world-class car collection. Topics Museum Gallery Plaza (near Your Place change daily and may include everything in Time) from the basics to a deep dive on one or January two cars. Check on-site signage for today’s offerings. We’ll bring in 2017 by highlighting the Mon.-Fri. 11:30, 12:30 and 3:00 best projects of 2016. Tinker with flight, Sat.-Sun. 10:30, 12:30 and 3:00 learn to solder with a simple LED badge*, Meet outside Drive-In Theater. make a tinkering journal and build a bot.* Great Father’s Day Outing! 67th Annual February Curator Close-Up Explore the evolution of vehicle power Motor Muster Old Car Festival sources including electrical generation, Greenfield Village • June 17-18, 2017 Greenfield Village • Sept. -

Wessex Vehicle Preservation Club Founded 1971

WESSEX VEHICLE PRESERVATION CLUB FOUNDED 1971 www.wvpc.org.uk ‘WESSEX WAYS’ MAY 2021 CHAIRMAN’S CHATTER Hi Everyone. Have just had the news that you will be ok to give someone a hug from next Monday, that won't make any difference to me as I'm quite happy not hugging and just being miserable !!! All joking aside it would appear that the end of the pandemic is just around the corner, we have a show soon and Mo and myself hope to see as many of you as possible also if things go to plan we may soon be back to having Club night back again, in the meantime you all drive with care, Doug. VEHICLE OF THE MONTH THE “MINI” The Mini came about because of a fuel shortage caused by the 1956 Suez Crisis. Petrol was once again rationed in the UK, sales of large cars slumped, and the market for German bubble cars boomed, even in countries such as Britain, where imported cars were still a rarity. The Fiat 500, launched in 1957, was also hugely successful, especially in its native Italy. Leonard Lord, the somewhat autocratic head of BMC, reportedly detested these cars so much that he vowed to rid the streets of them and design a 'proper miniature car'. He laid down some basic design requirements – the car should be contained within a box that measured 10×4×4 feet (3.0×1.2×1.2 m); and the passenger accommodation should occupy 6 feet (1.8 m) of the 10-foot (3.0 m) length; and the engine, for reasons of cost, should be an existing unit. -

Industrieabenteuer in Sachsen

Industrieabenteuer in Sachsen Industrieabenteuer in Sachsen Nach Kai Jensen – frei übertragen von Andreas Mascheck mit freundlicher Genehmigung seiner Witwe Allen in Ost und West ist der Trabant ein Begriff aber nur Wenige wissen um die genaue Geschichte dieses Autos und die Aufarbeitung der Industriegeschichte ist durch die politisch orientierte Geschichtsschreibung sowohl des 3. Reiches als auch der beiden deutschen Nachkriegs-Staaten recht ungenau. Große Erfindungen brachen und brechen sich ihren Weg in unser Leben nach oder mit Kriegen, hier sei an die Erfindungen des Archimedes während der Belagerung von Syrakus (Sardinien) durch die Römer bis 212 v.Chr., an die Beherrschung der Kernschmelze beim Bau der Atombombe und die durchaus nicht zivil zu sehende Eroberung des Weltraums (Peenemünde, Sputnik 1, Mercury ) erinnert, die uns seit Ende des kalten Krieges die massenweise Verwendung von sattelitengestützter Kommunikation und von Computern ermöglichte. Die massenweise Verbreitung von Verbrennungsmotoren zur Mobilisierung der Menschheit nahm ihren Anfang nach dem 1. Weltkrieg. Von nun an war klar welches Entwicklungs- und Machtpotential in den Verbrennungsmotoren liegt und wie wenig praktisch die bis dahin verwendeten Techniken waren. (Das ähnelt unserm heutigen Wissen über die Nutzung von Computertechnik – gut, aber wenig zuverlässig). Versetzen wir uns aber kurz in die Zeit vor dem 1. Weltkrieg nach Sachsen. Die Reichseinigung unter der Führung von Preußen und der gewonnene Deutsch-Französische Krieg 1871 hatte die ökonomischen und politischen Grundlagen für die sogenannte Gründerzeit geschaffen, in Deutschland dämmerte der Boom des industriellen Aufschwungs herauf. Siemens war auf dem Weg die internationale Elektroindustrie zu beherrschen, Krupp die Stahlindustrie und Autos wurden in Sachsen gebaut. 1904 begann das Industrieabenteuer des weithin unbekannten Dänen Jörgen Skafte Rasmussen, der die Industrieentwicklung in diesem Bereich nachhaltig geprägt hat, in Deutschland. -

Automobile Design History – What Can We Learn from the Behavior at the Edges?

AUTOMOBILE DESIGN HISTORY – WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM THE BEHAVIOR AT THE EDGES? Chris Dowlen Engineering and Design, London South Bank University, UK London South Bank University, Borough Road, London SE1 0AA, UK. [email protected] Automobile design history – what can we learn from the behavior at the edges? The paper is developed from a larger evaluation of the history of automobile design. This evaluation used categorical principal component analysis to analyze the direction of the product history, investigating how automobiles developed from 1878 to the present (2013), particularly focusing on whether automobile designers appear to be working within what are termed product paradigms. Rather than looking at how design thinking and paradigms became established in automobile design, this paper takes a sideways look at the variations and quirky automobiles that have been built by investigating the outliers of the analysis and categorizing them into three categories: those that are always outside of general trends, those that are throwbacks to earlier thinking and those that are innovative and ahead of later thinking. The paper ends with a brief look at how and why novelty might become innovation and hence alter the course of the greater product history rather than remaining outliers, interesting as they are. This is where the novelty demonstrates significant advantages for the customer and manufacturer. The conclusion is that the process of investigating statistical outliers is useful and may lead to insights when investigating changes, developments and innovations and their causes. Keywords: automotive design; product history, principal components analysis, innovation, outliers, out-of-the-box thinking 1. -

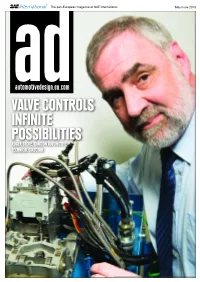

VALVE CONTROLS INFINITE POSSIBILITIES ROGER STONE, CAMCON AUTOMOTIVE TECHNICAL DIRECTOR Where All the Pieces Fall Into Place

The pan-European magazine of SAE International May/June 2013 VALVE CONTROLS INFINITE POSSIBILITIES ROGER STONE, CAMCON AUTOMOTIVE TECHNICAL DIRECTOR Where All the Pieces Fall Into Place Let’s face it; driveline design can be a real brainteaser. Reduced emissions. Improved fuel economy. Enhanced vehicle performance. Getting all the pieces to fit is challenging—especially when you can’t see the whole picture. That’s why you need one more piece to solve the driveline puzzle. Introducing DrivelineNEWS.com—a single, all-encompassing website exclusively dedicated to driveline topics for both on- and off-road vehicles. Log on for the latest news, market intelligence, technical innovations and hardware animations to help you find solutions and move your business forward. It takes ingenuity and persistence to succeed in today’s driveline market. Test your skills at DrivelineNEWS.com/Puzzle. Solve the puzzle to enter to win a Kindle Fire. © 2013 The Lubrizol Corporation. All rights reserved. 121569 Contents 12 12 Cover Story 5 Comment Valve controls Imagine a valve control system that is infinitely 6 variable irrespective of engine speed and load. News Impossible? Not according to Camcon Automotive’s • Exclusive: technical director Roger Stone, as Ian Adcock Engine knock discovers predicted 16 Biomimicry • Volvo diesel breakthrough Mother Nature knows best What can the automotive industry learn from nature • Driveline software when it comes to weight saving? Ryan Borroff has 20 been finding out • Four-way cat for petrol engines 20 Fuel injection systems Building up the pressure 11 Tony Lewin reports on the growing trend towards even The Columnist higher line pressures in injection systems. -

All-New Audi A3 - Quattro Drive Gets Its Moment in the Sun

AUDI UK Product and Technology Communications Yeomans Drive, Blakelands Milton Keynes MK14 5AN Tel: 01908 601407 / 01908 601980 Email: [email protected] / [email protected] 07 February 2020 All-new Audi A3 - quattro drive gets its moment in the sun Camouflaged versions of new Audi compact hatchback tackle a course also used for the Azores rally to demonstrate latest quattro technology quattro-equipped versions of all-new compact hatchback showcase the latest evolution of the world renowned technology Quick-witted: progressive steering with a variable ratio No need to compromise on agility or comfort: adaptive damper control Ingolstadt/Ponta Delgada, February 7, 2020 – Roads considered challenging enough to be a test of mettle for thoroughbred competition cars on the Azores rally have been chosen to provide a baptism of fire for the quattro system underpinning the all-new Audi A3. Journalists have been able to assess the dynamic capabilities of all-wheel- drive versions of the advanced new compact hatchback on these roads, which snake around the island of São Miguel in Portugal’s Azores archipelago, ahead of the car’s world public debut at next month’s Geneva Motor Show. Pure emotion: the original thought In a place where volcanoes once created a whole chain of islands and where there is a high level of volcanic activity, Audi is demonstrating the core of its DNA: quattro drive. The all-wheel drive system fittingly makes its first appearance in one of the most emotive versions of the fourth generation A3, and represents the latest stage in the evolution of this successful technology, which in Audi models with transverse engine installations is based around an electro-hydraulic multi plate clutch.