Answer Brief John F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Notices & the Courts

PUBLIC NOTICES B1 DAILY BUSINESS REVIEW TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2021 dailybusinessreview.com & THE COURTS BROWARD PUBLIC NOTICES BUSINESS LEADS THE COURTS WEB SEARCH FORECLOSURE NOTICES: Notices of Action, NEW CASES FILED: US District Court, circuit court, EMERGENCY JUDGES: Listing of emergency judges Search our extensive database of public notices for Notices of Sale, Tax Deeds B5 family civil and probate cases B2 on duty at night and on weekends in civil, probate, FREE. Search for past, present and future notices in criminal, juvenile circuit and county courts. Also duty Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach. SALES: Auto, warehouse items and other BUSINESS TAX RECEIPTS (OCCUPATIONAL Magistrate and Federal Court Judges B14 properties for sale B8 LICENSES): Names, addresses, phone numbers Simply visit: CALENDARS: Suspensions in Miami-Dade, Broward, FICTITIOUS NAMES: Notices of intent and type of business of those who have received https://www.law.com/dailybusinessreview/public-notices/ and Palm Beach. Confirmation of judges’ daily motion to register business licenses B3 calendars in Miami-Dade B14 To search foreclosure sales by sale date visit: MARRIAGE LICENSES: Name, date of birth and city FAMILY MATTERS: Marriage dissolutions, adoptions, https://www.law.com/dailybusinessreview/foreclosures/ DIRECTORIES: Addresses, telephone numbers, and termination of parental rights B8 of those issued marriage licenses B3 names, and contact information for circuit and CREDIT INFORMATION: Liens filed against PROBATE NOTICES: Notices to Creditors, county -

Maryland Casualty Producer State and General Sections Series 20-07 & 20-08 80 Scored Questions (Plus 10 Unscored)

Maryland Casualty Producer State and General Sections Series 20-07 & 20-08 80 scored questions (plus 10 unscored) Casualty Producer State Section Series 20-08 35 questions- 45-minute time limit 1.0 Insurance Regulation 1.1 Licensing 17% (5 items) Purpose Process (Insurance Article Annotated Code- Sec. 10-115; Sec.10-116; Sec. 10-104) Initial Licensure Qualifications Examination License fee & application Exemptions to Licensure Types of licensees Producers Business entity producers Nonresident producers Temporary Advisers Public insurance adjusters Limited Lines Producer Portable Electronics Insurance Limited Lines license Maintenance and duration (Insurance Article Annotated Code- Sec. 10-116; Sec. 10-117(b)(1)) Reinstatement and renewal Address change Reporting of actions Assumed names Continuing education requirements, exemptions and penalties Disciplinary actions Cease and desist order Hearings Probation, suspension, revocation, refusal to issue or renew Penalties and fines 1.2 State regulation 17% (5 items) Commissioner's general duties and powers (Insurance Article Annotated Code-Sec. 2-205 (a)(2)) State Specific Definitions (Insurance Article Annotated Code- Sec. 10-401; Sec. 27-209; Sec. 27-213; Sec. 10-201; Sec 10-126; Ref: COMAR Sec. 31.08.06.02) Company regulation Certificate of authority Solvency Rates Policy forms Examination of books and records Producer appointments Producer's Contract with Insurer versus Producer's Appointment with Insurer 1 Producer's Individual Appointment versus Business Entity Appointment Maintaining Record of Appointment Notice Termination of producer appointment Producer regulation (Insurance Article Annotated Code-Sec. 27-212(d)) Examination of Books and Records Insurance Information and Privacy Protection Fiduciary Responsibilities (COMAR- Sec. 31.03.03) Bail Bond (COMAR- Sec. -

DACIN SARA Repartitie Aferenta Trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU

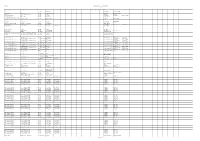

DACIN SARA Repartitie aferenta trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 R10 R11 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 Greg Pruss - Gregory 13 13 2010 US Gela Babluani Gela Babluani Pruss 1000 post Terra After Earth 2013 US M. Night Shyamalan Gary Whitta M. Night Shyamalan 30 de nopti 30 Days of Night: Dark Days 2010 US Ben Ketai Ben Ketai Steve Niles 300-Eroii de la Termopile 300 2006 US Zack Snyder Kurt Johnstad Zack Snyder Michael B. Gordon 6 moduri de a muri 6 Ways to Die 2015 US Nadeem Soumah Nadeem Soumah 7 prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul / Sapte The Seven Little Foys 1955 US Melville Shavelson Jack Rose Melville Shavelson prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul A 25-a ora 25th Hour 2002 US Spike Lee David Benioff Elaine Goldsmith- A doua sansa Second Act 2018 US Peter Segal Justin Zackham Thomas A fost o data in Mexic-Desperado 2 Once Upon a Time in Mexico 2003 US Robert Rodriguez Robert Rodriguez A fost odata Curly Once Upon a Time 1944 US Alexander Hall Lewis Meltzer Oscar Saul Irving Fineman A naibii dragoste Crazy, Stupid, Love. 2011 US Glenn Ficarra John Requa Dan Fogelman Abandon - Puzzle psihologic Abandon 2002 US Stephen Gaghan Stephen Gaghan Acasa la coana mare 2 Big Momma's House 2 2006 US John Whitesell Don Rhymer Actiune de recuperare Extraction 2013 US Tony Giglio Tony Giglio Acum sunt 13 Ocean's Thirteen 2007 US Steven Soderbergh Brian Koppelman David Levien Acvila Legiunii a IX-a The Eagle 2011 GB/US Kevin Macdonald Jeremy Brock - ALCS Les aventures extraordinaires d'Adele Blanc- Adele Blanc Sec - Aventurile extraordinare Luc Besson - Sec - The Extraordinary Adventures of Adele 2010 FR/US Luc Besson - SACD/ALCS ale Adelei SACD/ALCS Blanc - Sec Adevarul despre criza Inside Job 2010 US Charles Ferguson Charles Ferguson Chad Beck Adam Bolt Adevarul gol-golut The Ugly Truth 2009 US Robert Luketic Karen McCullah Kirsten Smith Nicole Eastman Lebt wohl, Genossen - Kollaps (1990-1991) - CZ/DE/FR/HU Andrei Nekrasov - Gyoergy Dalos - VG. -

Civilian Killings and Disappearances During Civil War in El Salvador (1980–1992)

DEMOGRAPHIC RESEARCH A peer-reviewed, open-access journal of population sciences DEMOGRAPHIC RESEARCH VOLUME 41, ARTICLE 27, PAGES 781–814 PUBLISHED 1 OCTOBER 2019 http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol41/27/ DOI: 10.4054/DemRes.2019.41.27 Research Article Civilian killings and disappearances during civil war in El Salvador (1980–1992) Amelia Hoover Green Patrick Ball c 2019 Amelia Hoover Green & Patrick Ball. This open-access work is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Germany (CC BY 3.0 DE), which permits use, reproduction, and distribution in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are given credit. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/de/legalcode Contents 1 Introduction 782 2 Background 783 3 Methods 785 3.1 Methodological overview 785 3.2 Assumptions of the model 786 3.3 Data sources 787 3.4 Matching and merging across datasets 790 3.5 Stratification 792 3.6 Estimation procedure 795 4 Results 799 4.1 Spatial variation 799 4.2 Temporal variation 802 4.3 Global estimates 803 4.3.1 Sums over strata 805 5 Discussion 807 6 Conclusions 808 References 810 Demographic Research: Volume 41, Article 27 Research Article Civilian killings and disappearances during civil war in El Salvador (1980–1992) Amelia Hoover Green1 Patrick Ball2 Abstract BACKGROUND Debate over the civilian toll of El Salvador’s civil war (1980–1992) raged throughout the conflict and its aftermath. Apologists for the Salvadoran regime claimed no more than 20,000 had died, while some activists placed the toll at 100,000 or more. -

American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics

American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Updated July 29, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL32492 American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Summary This report provides U.S. war casualty statistics. It includes data tables containing the number of casualties among American military personnel who served in principal wars and combat operations from 1775 to the present. It also includes data on those wounded in action and information such as race and ethnicity, gender, branch of service, and cause of death. The tables are compiled from various Department of Defense (DOD) sources. Wars covered include the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican War, the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam Conflict, and the Persian Gulf War. Military operations covered include the Iranian Hostage Rescue Mission; Lebanon Peacekeeping; Urgent Fury in Grenada; Just Cause in Panama; Desert Shield and Desert Storm; Restore Hope in Somalia; Uphold Democracy in Haiti; Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF); Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF); Operation New Dawn (OND); Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR); and Operation Freedom’s Sentinel (OFS). Starting with the Korean War and the more recent conflicts, this report includes additional detailed information on types of casualties and, when available, demographics. It also cites a number of resources for further information, including sources of historical statistics on active duty military deaths, published lists of military personnel killed in combat actions, data on demographic indicators among U.S. military personnel, related websites, and relevant CRS reports. Congressional Research Service American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... -

MASS CASUALTY TRAUMA TRIAGE PARADIGMS and PITFALLS July 2019

1 Mass Casualty Trauma Triage - Paradigms and Pitfalls EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Emergency medical services (EMS) providers arrive on the scene of a mass casualty incident (MCI) and implement triage, moving green patients to a single area and grouping red and yellow patients using triage tape or tags. Patients are then transported to local hospitals according to their priority group. Tagged patients arrive at the hospital and are assessed and treated according to their priority. Though this triage process may not exactly describe your agency’s system, this traditional approach to MCIs is the model that has been used to train American EMS As a nation, we’ve got a lot providers for decades. Unfortunately—especially in of trailers with backboards mass violence incidents involving patients with time- and colored tape out there critical injuries and ongoing threats to responders and patients—this model may not be feasible and may result and that’s not what the focus in mis-triage and avoidable, outcome-altering delays of mass casualty response is in care. Further, many hospitals have not trained or about anymore. exercised triage or re-triage of exceedingly large numbers of patients, nor practiced a formalized secondary triage Dr. Edward Racht process that prioritizes patients for operative intervention American Medical Response or transfer to other facilities. The focus of this paper is to alert EMS medical directors and EMS systems planners and hospital emergency planners to key differences between “conventional” MCIs and mass violence events when: • the scene is dynamic, • the number of patients far exceeds usual resources; and • usual triage and treatment paradigms may fail. -

James Hillier

14 City Lofts 112-116 Tabernacle Street London EC2A 4LE offi[email protected] +44 (0) 20 7734 6441 JAMES HILLIER Shadow & Bone Small Axe The Crown Television Role Title Production Company Director DCI Bill Raynott STEPHEN Hat Trick for ITV Alrick Riley Tony Leech DECEIT Story Films Niall MacCormack Jack Cocker CLOSE TO ME Viaplay / Channel 4 Michael Samuels Captain Churik SHADOW & BONE 21 Laps Entertainment / Netflix Lee Toland Krieger / Eric Heisserer Chief Inspector SMALL AXE BBC / Amazon Studios Steve McQueen Dr Stu Ford DOCTORS BBC Dan Wilson The Equerry (Series Regular) THE CROWN SEASON TWO Left Bank Pictures / Netflix Stephen Daldry Nathan Stone PRIME SUSPECT 1973 Noho / ITV David Caffrey The Equerry (Series Regular) THE CROWN SEASON ONE TVE Various Oliver Grau (Series Regular) MERLÍ SEASON 1 Left Bank Pictures / Netflix Stephen Daldry Joseph McCoy FRONTIER Raw TV Ben Chanan James Downing CASUALTY BBC Jon Sen Admiral Nelson THE BRITISH Nutopia Jenny Ash Chris LONDON’S BURNING Juniper Justin Hardy Mick SURVIVORS BBC Ian B. McDonald Sgt Christian Young (Series HOLBY BLUE SERIES TWO BBC / Kudos Martin Hutchins Regular) Damian EASTENDERS BBC Michael Kellior Sgt Christian Young (Series HOLBY BLUE SERIES ONE BBC / Kudos Martin Hutchins Regular) Keith Spalding GOLDPLATED Channel 4 Julie Ann Robinson / Robert Delamere Robert Barrie (Recurring) THE BILL Talkback Thames Bill Scot-Rider Marcus Octavius THE RISE AND FALL OF ROME: BBC Chris Spencer REVOLUTION Garret Gibbens BLACKBEARD Dangerous Films Richard Dale Darren HOLBY CITY BBC Nick Adams Jeremy -

Hippocrates Now

Hippocrates Now 35999.indb 1 11/07/2019 14:48 Bloomsbury Studies in Classical Reception Bloomsbury Studies in Classical Reception presents scholarly monographs offering new and innovative research and debate to students and scholars in the reception of Classical Studies. Each volume will explore the appropriation, reconceptualization and recontextualization of various aspects of the Graeco- Roman world and its culture, looking at the impact of the ancient world on modernity. Research will also cover reception within antiquity, the theory and practice of translation, and reception theory. Also available in the Series: Ancient Magic and the Supernatural in the Modern Visual and Performing Arts, edited by Filippo Carlà & Irene Berti Ancient Greek Myth in World Fiction since 1989, edited by Justine McConnell & Edith Hall Antipodean Antiquities, edited by Marguerite Johnson Classics in Extremis, edited by Edmund Richardson Frankenstein and its Classics, edited by Jesse Weiner, Benjamin Eldon Stevens & Brett M. Rogers Greek and Roman Classics in the British Struggle for Social Reform, edited by Henry Stead & Edith Hall Homer’s Iliad and the Trojan War: Dialogues on Tradition, Jan Haywood & Naoíse Mac Sweeney Imagining Xerxes, Emma Bridges Julius Caesar’s Self-Created Image and Its Dramatic Afterlife, Miryana Dimitrova Once and Future Antiquities in Science Fiction and Fantasy, edited by Brett M. Rogers & Benjamin Eldon Stevens Ovid’s Myth of Pygmalion on Screen, Paula James Reading Poetry, Writing Genre, edited by Silvio Bär & Emily Hauser -

Fostering and Measuring Skills: Improving Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Skills to Promote Lifetime Success

Fostering and Measuring Skills: Improving Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Skills to Promote Lifetime Success Tim Kautz, James J. Heckman, Ron Diris, Bas ter Weel, Lex Borghans Directorate for Education and Skills Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI) Education and Social Progress www.oecd.org/edu/ceri/educationandsocialprogress.htm FOSTERING AND MEASURING SKILLS: IMPROVING COGNITIVE AND NON-COGNITIVE SKILLS TO PROMOTE LIFETIME SUCCESS This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: © Shutterstock You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgment of the source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was commissioned by the OECD through its project on Education and Social Progress. We thank Linor Kiknadze and Edward Sung for valuable research assistance. -

'A Child's Heart'

Casualty 30 Episode 1 - Scene 1 1 EXT. UNDERWATER (TANK) - NIGHT (22:15) (ZOE) ZOE is fighting for her life. Her wedding dress is making it impossible for her to swim. CUT TO: Episode 1 - PRODUCTION - 'A Child's Heart - Part 1' 1 Casualty 30 Episode 1 - Scene 2 2 EXT. RIVER. - NIGHT. CONTINUOUS (22:15) (ZOE) ZOE bursts the surface but is in real trouble. She gulps desperately before she goes down again. CUT TO: Episode 1 - PRODUCTION - 'A Child's Heart - Part 1' 2 Casualty 30 Episode 1 - Scene 3 3 EXT. RIVER BANK. - NIGHT. CONTINUOUS (22:15) (ETHAN, LOFTY, LOUIS, ROBYN) (DYLAN, CHARLIE, HONEY, MAX, BIG MAC, ZOE) DYLAN’s boat has just exploded. He is silhouetted by flames. On the river bank, CHARLIE has seen ZOE struggling beyond the boat. He pulls off his jacket, kicks off his shoes. LOUIS Dad? What are you doing? CHARLIE clambers down into the river. The cold hits him but he pushes on. LOUIS runs to the bank - shouting: LOUIS (CONT’D) Dad! Dad! But CHARLIE has disappeared. Smoke from DYLAN’s boat hangs thick over the water. LOUIS turns: running from the burning marquee come MAX, ETHAN, LOFTY, HONEY, BIG MAC, ROBYN and other NS guests... LOFTY (shouting) Dylan jump! Jump! LOUIS panics and scurries away. As they run forward ETHAN is dialling 999. The point is everyone is focused on DYLAN who seems almost frozen on his burning boat. ROBYN Jump! You can jump... ETHAN (in the background) Ambulance please - fire... Yes the fire brigade have been called. -

Mass Casualty Incident (MCI) Response Module 1

Mass Casualty Incident (MCI) Response Module 1 (Hamilton County Fire Chief's Association, 2013) 1 Objectives Purpose: This module will educate staff on mass casualty triage incident response, including how to: • Define mass casualty triage • Determine considerations for adults and pediatrics • Understand the importance of a patient tracking system • Recognize and implement the patient admission/ discharge MCI triage process • Determine how to appropriately handle the deceased in a large-scale MCI • Recognize the range of incidents that may cause MCIs 2 MCI Basics 3 What is an MCI? • A mass casualty incident (MCI) is an incident where the number of patients exceeds the amount of healthcare resources available. • This number varies widely across the country, but is typically greater than 10 patients. 4 Types of MCI Notifications • During a large scale incident such as a mass casualty, it is important to have a mass notification system. Successful mass notification systems will: . Internally: alert staff to activate MCI protocols and prepare for a potential surge of patients . Externally: increase community awareness 5 Assisting in MCI Response Considerations for hospital staff in an MCI: • Some patients may arrive to the hospital without having been assessed/ triaged at the scene • MCI response requires efficiency and coordination • Non-clinical personnel (including hospital volunteers) can assist in moving patients to designated areas based on level of care • Help gather patient information in the emergency treatment area • Staff should review patients in clinical assignment for any potential discharges/ transfers to make room for potential MCI admissions, a process known as “surge discharge” (Chung S, 2019) 6 Triage Basics Definition of MCI Triage Triage means “to sort.” Triage in an MCI is the assignment of resources based on the initial patient assessment and consideration of available resources. -

Water on the Rise: Protecting Canadian Homes from the Growing Threat of Flooding

WATER ON THE RISE: PROTECTING CANADIAN HOMES FROM THE GROWING THREAT OF FLOODING CHERYL EVANS AND DR. BLAIR FELTMATE | INTACT CENTRE ON CLIMATE ADAPTATION | APRIL 2019 GENEROUSLY SUPPORTED BY: ABOUT THE INTACT CENTRE ON CLIMATE ABOUT THE INSURANCE BUREAU OF CANADA ADAPTATION Insurance Bureau of Canada (IBC) is the national industry The Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation (Intact Centre) is association representing Canada’s private home, auto an applied research centre at the University of Waterloo. and business insurers. Its member companies make up 90% The Intact Centre was founded in 2015 with a gift from of the property and casualty (P&C) insurance market Intact Financial Corporation, Canada’s largest property in Canada. For more than 50 years, IBC has worked with and casualty insurer. The Intact Centre helps homeowners, governments across the country to help make affordable home, communities and businesses to identify and reduce risks auto and business insurance available for all Canadians. associated with climate change and extreme weather events. ABOUT THE CITY OF BURLINGTON ABOUT THE UNIVERSITY OF WATERLOO The City of Burlington is in the Regional Municipality of Halton, University of Waterloo is Canada’s top innovation university. Ontario. With a population of 183,314 (2016 Census), the City of With more than 36,000 students, the university is home to Burlington is located at the northwestern end of Lake Ontario. the world’s largest co-operative education system of its kind. The university’s unmatched entrepreneurial culture ABOUT THE CITY OF TORONTO combined with an intensive focus on research powers one The City of Toronto is the capital city of Ontario and also the of the top innovation hubs in the world.