Borat and the Problem of Parody Bronwen Low

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Working Draft Raw Materials, Creative Works, and Cultural

Early Working Draft Raw Materials, Creative Works, and Cultural Hierarchies Andrew Gilden In disputes involving creative works, courts increasingly ask whether a preexisting text, image or persona has been used as “raw material” for new authorship. If so, the accused infringer becomes shielded by the fair use doctrine under copyright law or a First Amendment defense under right of publicity law. Although copyright and right of publicity decisions have begun to rely heavily on the concept, neither the case law nor existing scholarship has explored what it actually means to use something as “raw material,” whether this inquiry adequately draws lines between infringing and non- infringing conduct, or how well it maps onto the expressive values that the fair use doctrine and the First Amendment defense aim to capture This Article reveals serious problems with the raw material inquiry. First, a survey of all decisions invoking raw materials uncovers troubling distributional patterns; in nearly every case the winner is the party in the more privileged class, race or gender position. Notwithstanding courts’ assurance that the inquiry is “straightforward,” distinctions between raw and “cooked” materials appear to be structured by a range of social hierarchies operating in the background. Second, these cases express ethically troubling messages about the use and reuse of text, image and likeness. The more offensive, callous and objectionable the appropriation, the more visibly “raw” the preexisting material is likely to be. Given the shortcomings of the raw material inquiry, this Article argues that courts should engage more directly with an accused infringer’s actual creative process and rely less on a formal comparison between the two works in dispute. -

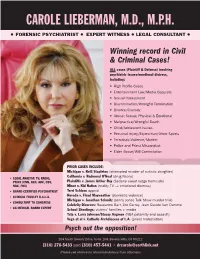

Carole Lieberman, M.D., M.P.H

CAROLE LIEBERMAN, M.D., M.P.H. l FORENSIC PSYCHIATRIST l EXPERT WITNESS l LEGAL CONSULTANT l Winning record in Civil & Criminal Cases! ALL cases (Plaintiff & Defense) involving psychiatric issues/emotional distress, including: • High Profile Cases • Entertainment Law/Media Copycats • Sexual Harassment • Discrimination/Wrongful Termination • Divorce/Custody • Abuse: Sexual, Physical & Emotional • Malpractice/Wrongful Death • Child/Adolescent issues • Personal Injury/Equestrian/Other Sports • Terrorism/Violence/Murder • Police and Priest Misconduct • Elder Abuse/Will Contestation PRIOR CASES INCLUDE: Michigan v. Kelli Stapleton (attempted murder of autistic daughter) California v. Redmond O’Neal • LEGAL ANALYST: TV, RADIO, (drug felony) Plaintiffs v. James Arthur Ray PRINT (CNN, HLN, ABC, CBS, (Sedona sweat lodge homicide) NBC, FOX) Minor v. Kid Nation (reality TV → emotional distress) Terri Schiavo • BOARD CERTIFIED PSYCHIATRIST appeal Nevada v. Floyd Mayweather • CLINICAL FACULTY U.C.L.A. (domestic violence) Michigan v. Jonathan Schmitz • CONSULTANT TO CONGRESS (Jenny Jones Talk Show murder trial) Celebrity Divorces: Roseanne Barr, Jim Carrey, Jean Claude Van Damme • CA MEDICAL BOARD EXPERT School Shootings: victims’ families v. media Tate v. Larry Johnson/Stacey Augman (NBA paternity and assault) Vega et al v. Catholic Archdiocese of L.A. (priest molestation) Psych out the opposition! 204 South Beverly Drive, Suite 108, Beverly Hills, CA 90212 (310) 278-5433 (310) 457-5441 [email protected] and • (Please see reverse for recommendations from attorneys) Here’s what your colleagues are saying about Carole Lieberman, M.D. Psychiatrist and Expert Witness: “I have had the opportunity to work with the “I have rarely had the good fortune to present best expert witnesses in the business, and I such well-considered testimony from such a would put Dr. -

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories PAUL A. CRUTCHER DAPTATIONS OF GRAPHIC NOVELS AND COMICS FOR MAJOR MOTION pictures, TV programs, and video games in just the last five Ayears are certainly compelling, and include the X-Men, Wol- verine, Hulk, Punisher, Iron Man, Spiderman, Batman, Superman, Watchmen, 300, 30 Days of Night, Wanted, The Surrogates, Kick-Ass, The Losers, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, and more. Nevertheless, how many of the people consuming those products would visit a comic book shop, understand comics and graphic novels as sophisticated, see them as valid and significant for serious criticism and scholarship, or prefer or appreciate the medium over these film, TV, and game adaptations? Similarly, in what ways is the medium complex according to its ad- vocates, and in what ways do we see that complexity in Batman graphic novels? Recent and seminal work done to validate the comics and graphic novel medium includes Rocco Versaci’s This Book Contains Graphic Language, Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, and Douglas Wolk’s Reading Comics. Arguments from these and other scholars and writers suggest that significant graphic novels about the Batman, one of the most popular and iconic characters ever produced—including Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley’s Dark Knight Returns, Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum, and Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s Killing Joke—can provide unique complexity not found in prose-based novels and traditional films. The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2011 r 2011, Wiley Periodicals, Inc. -

Celebrities Who Give Us Nightmares Reality Show Fame Can Be Lucrative (Just Look at Bethenny Frankel) but It Can Also Go Horribly Wrong

Dorothy Pomerantz, Forbes Staff I write about Hollywood and run the Celebrity 100 List. BUSINESS 10/31/2012 @ 2:08PM Celebrities Who Give Us Nightmares Reality show fame can be lucrative (just look at Bethenny Frankel) but it can also go horribly wrong. Spencer Pratt made a splash with his villainous performance on The Hills, but since then his career hasn’t work out quite like he had hoped. Instead of writing books, starting a fashion line and producing more TV, Pratt ended up standing by Heidi Montag’s side while she underwent multiple plastic surgeries to turn herself into the world’s saddest living Barbie doll. Perhaps that’s why the public sees Pratt as the creepiest Just in time for Halloween, here are the celebrities who creep America out the most, based on survey celebrity out there, according to E-Poll Market data from E-Poll Market Research, whose E-Score Research. E-Poll’s E-Score Celebrity service ranks more Celebrity service ranks more than 6,000 celebrities on awareness, appeal and 46 different personality than 6,000 celebrities on public awareness, appeal and 46 attributes. Its survey results show that in different personality attributes. When asked to rate Pratt, Hollywood, no one is as scary as reality show stars. 49% of survey respondents said they found him creepy. Another reality star who creeps us all out: Courtney Stodden. The teen is best-known for marrying 50- year-old actor Doug Hutchinson when she was only 16. Somehow, these two are still getting publicity. Maybe it’s because of the way Stodden dresses. -

Congressional Record-House. 8651

1922.- CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. 8651 3,281,000,000 bushels of corn, with a value of approximately $1,9<.lS,- of navigation at or near Freeport, in the State of Pennsylvania in 600,000. This corn must find an outlet outside of the corn belt, either accordance with the provisions of the act entitled "An act to regUiate through feeding or export. History shows that practically 85 per cent ~i ~onstruction of bridges over navigable waters," ~pproved :March 23, of the corn raised in the United States must be fed on the farm. 6 The competition of blackstrap molasses in displacing corn for feeding S»C. 2. That the right to alter, amend, or repeal this act is hereby and distilling purposes is greatly Increasing our surplus and has a very expressly reserved. depressing effect on our market. The import duty will have a very beneficial effect of restoring the value of our product. The bill was reported to the Senate without amendment, or When this amendment comes up ·on the tloor of the Senate, we urge dered to a third reading, read the third time, and passed. you to support it, thereby protecting the products of the American farmer instead of permitting the waste products f9>m foreign countriea. EXECUTIVE SESSION. to enter this country free of duty and depress the market of 011r farmers' main crop--corn. Mr. JONES of Washington. I move that the Senate proceed Respectfully submitted. • to the consideration of executive business. Peoria County Farm Bureau, per Zealy M. Holmes, presi dent ; The American Distilling Co., Pekin, Ill., per The motion was agreed to ; and the Senate proceeded to the E. -

Humor & Classical Music

Humor & Classical Music June 29, 2020 Humor & Classical Music ● Check the Tech ● Introductions ● Humor ○ Why, When, How? ○ Historic examples ○ Oddities ○ Wrap-Up Check the Tech ● Everything working? See and hear? ● Links in the chat ● Zoom Etiquette ○ We are recording! Need to step out? Please stop video. ○ Consider SPEAKER VIEW option. ○ Please remain muted to reduce background noise. ○ Questions? Yes! In the chat, please. ○ We will have Q&A at the end. Glad you are here tonight! ● Steve Kurr ○ Middleton HS Orchestra Teacher ○ Founding Conductor - Middleton Community Orchestra ○ M.M. and doctoral work in Musicology from UW-Madison ■ Specialties in Classic Period and Orchestra Conducting ○ Continuing Ed course through UW for almost 25 years ○ Taught courses in Humor/Music and also performed it. WHAT makes humorous music so compelling? Music Emotion with a side order of analytical thinking. Humor Analytical thinking with a side order of emotion. WHY make something in music funny? 1. PARODY for humorous effect 2. PARODY for ridicule [tends toward satire] 3. Part of a humorous GENRE We will identify the WHY in each of our examples tonight. HOW is something in music made funny? MUSIC ITSELF and/or EXTRAMUSICAL ● LEVEL I: Surface ● LEVEL II: Intermediate ● LEVEL III: Deep We will identify the levels in each of our examples tonight. WHEN is something in music funny? ● Broken Expectations ● Verisimilitude ● Context Historic Examples: Our 6 Time Periods ● Medieval & Renaissance & Baroque ○ Church was primary venue, so humor had limits (Almost exclusively secular). ● Classic ○ Music was based on conventions, and exploration of those became the humor of the time. ● Romantic ○ Humor was not the prevailing emotion explored--mainly used in novelties. -

Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modern Political Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart." Social Research 79.1 (Spring 2012): 1-32

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (Classical Studies) Classical Studies at Penn 2012 Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modernolitical P Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart Ralph M. Rosen University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Rosen, R. M. (2012). Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modernolitical P Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/33 Rosen, Ralph M. "Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modern Political Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart." Social Research 79.1 (Spring 2012): 1-32. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/social_research/summary/v079/ 79.1.rosen.html Copyright © 2012 The Johns Hopkins University Press. This article first appeared in Social Research: An International Quarterly, Volume 79, Issue 1, Spring, 2012, pages 1-32. Reprinted with permission by The Johns Hopkins University Press. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/33 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modernolitical P Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart Keywords Satire, Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, Jon Stewart Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Classics Comments Rosen, Ralph M. "Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modern Political Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart." Social Research 79.1 (Spring 2012): 1-32. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/ social_research/summary/v079/79.1.rosen.html Copyright © 2012 The Johns Hopkins University Press. This article first appeared in Social Research: An International Quarterly, Volume 79, Issue 1, Spring, 2012, pages 1-32. -

Parody, Popular Culture, and the Narrative of Javier Tomeo

PARODY, POPULAR CULTURE, AND THE NARRATIVE OF JAVIER TOMEO by MARK W. PLEISS B.A., Simpson College, 2007 M.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Spanish and Portuguese 2015 This thesis entitled: Parody, Popular Culture, and the Narrative of Javier Tomeo written by Mark W. Pleiss has been approved for the Department of Spanish and Portuguese __________________________________________________ Dr. Nina L. Molinaro __________________________________________________ Dr. Juan Herrero-Senés __________________________________________________ Dr. Tania Martuscelli __________________________________________________ Dr. Andrés Prieto __________________________________________________ Dr. Robert Buffington Date __________________________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and We find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the abovementioned discipline. iii Pleiss, Mark W. (Ph.D. Spanish Literature, Department of Spanish and Portuguese) Parody, Popular Culture, and the Narrative of Javier Tomeo Dissertation Director: Professor Nina L. Molinaro My thesis sketches a constellation of parodic Works Within the contemporary Spanish author Javier Tomeo's (1932-2013) immense literary universe. These novels include El discutido testamento de Gastón de Puyparlier (1990), Preparativos de viaje (1996), La noche del lobo (2006), Constructores de monstruos (2013), El cazador de leones (1987), and Los amantes de silicona (2008). It is my contention that the Aragonese author repeatedly incorporates and reconfigures the conventions of genres and sub-genres of popular literature and film in order to critique the proliferation of mass culture in Spain during his career as a writer. -

Legendary Bonkerz Comedy Club to Open at the Plaza Hotel & Casino

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 11, 2013 MEDIA CONTACTS: Amy E. S. Maier, B&P PR, 702-372-9919, [email protected] Legendary Bonkerz Comedy Club to open at the Plaza Hotel & Casino on April 18 Tweet it: Get ready to laugh as @BonkerzComedy Club brings its hilarious comedians to entertain audiences @Plazalasvegas starting April 18 LAS VEGAS – The Plaza Hotel & Casino will be the new home of the historic Bonkerz comedy club and its cadre of comedy acts beginning April 18. Bonkerz Comedy Productions opened its doors in 1984 and has more than two dozen locations nationwide. As one of the nation’s longest-running comedy clubs, Bonkerz has been the site for national TV specials on Showtime, Comedy Central, MTV, Fox and “America´s Funniest People.” Many of today’s hottest comedians have taken their turn on the Bonkerz Comedy Club stage, including Larry The Cable Guy, Carrot Top, SNL co-star Darrell Hammond and Billy Gardell, star of the CBS hit sitcom “Mike and Molly.” Bonkerz owner Joe Sanfelippo has a long history of successful comic casting and currently consults with NBC’s “America’s Got Talent.” “Bonkerz has always had an outstanding reputation for attracting top-tier comedians and entertaining audiences,” said Michael Pergolini, general manager of the Plaza Hotel and Casino. “As we continue to expand our entertainment offerings, we are proud to welcome Bonkerz to the comedy club at the Zbar and know its acts will keep our guests laughing out loud.” “I am extremely excited to bring the Bonkerz brand to an iconic location like the Plaza,” added Bonkerz owner Joe Sanfelippo. -

James Phelan, Peter J. Rabinowitz, and Robyn Warhol, Series Editors

THEORY AND INTERPRETATION OF NARRATIVE James Phelan, Peter J. Rabinowitz, and Robyn Warhol, Series Editors Narrative Theory Core Concepts and Critical Debates DAVID HERMAN JAMES PHELAN PETER J. RABINOWITZ BRIAN RICHARDSON ROBYN WARHOL THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS | COLUMBUS Copyright © 2012 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Narrative theory : core concepts and critical debates / David Herman ... [et al.]. p. cm. — (Theory and interpretation of narrative) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-5184-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8142-5184-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8142-1186-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8142-1186-0 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0-8142-9285-3 (cd-rom) 1. Narration (Rhetoric) I. Herman, David, 1962– II. Series: Theory and interpretation of nar- rative series. PN212.N379 2012 808.036—dc23 2011049224 Cover design by James Baumann Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Minion Pro Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materi- als. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Preface ix Acknowledgments xiii Part One Perspectives: Rhetorical, Feminist, Mind-Oriented, Antimimetic 1. Introduction: The Approaches Narrative as Rhetoric JAMES PHElan and PETER J. Rabinowitz 3 A Feminist Approach to Narrative RobYN Warhol 9 Exploring the Nexus of Narrative and Mind DAVID HErman 14 Antimimetic, Unnatural, and Postmodern Narrative Theory Brian Richardson 20 2. Authors, Narrators, Narration JAMES PHElan and PETER J. -

Tom Hanks Halle Berry Martin Sheen Brad Pitt Robert Deniro Jodie Foster Will Smith Jay Leno Jared Leto Eli Roth Tom Cruise Steven Spielberg

TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND MARION COTILLARD KIRSTEN DUNST STEVE BUSCEMI ELIJAH WOOD RESSE WITHERSPOON MICKEY ROURKE AUDREY HEPBURN STEVE CARELL AL PACINO JIM CARREY SHARON STONE MEL GIBSON 2017-18 CATALOG SAM NEILL CHRIS HEMSWORTH MICHAEL SHANNON KIRK DOUGLAS ICE-T RENEE ZELLWEGER ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG CONTENTS 2 INDEPENDENT | FOREIGN | ARTHOUSE 23 HORROR | SLASHER | THRILLER 38 FACTUAL | HISTORICAL 44 NATURE | SUPERNATURAL MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN 45 WESTERNS SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO 48 20TH CENTURY TELEVISION LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA 54 SCI-FI | FANTASY | SPACE DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW 57 POLITICS | ESPIONAGE | WAR SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST 60 ART | CULTURE | CELEBRITY MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE 64 ANIMATION | FAMILY WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND 78 CRIME | DETECTIVE -

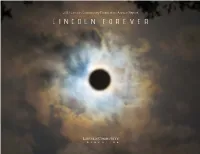

2017 Lincoln Community Foundation Annual Report 2017 OVERVIEW

2017 Lincoln Community Foundation Annual Report 2017 OVERVIEW “There seemed to be nothing to see; no fences, no creeks or trees, no hills or fields. If there was a road, I could not make it out in the faint starlight. There was nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made.” Willa Cather, My Antonia, 1918 The Lincoln Community Foundation found We have inherited the grit and wisdom of our TO HELP BUILD A GREAT CITY; TO ways to support the inspiring opportunities in our ancestors who launched this state over 150 years NURTURE, HARNESS AND DIRECT THAT community: ago, built a land grant university referenced by ENERGY, IS THE ASPIRATION OF THE others as the Harvard on the Prairie, constructed a • In honor of the state’s sesquicentennial, a gift state of the art Capitol during the depression that LINCOLN COMMUNITY FOUNDATION. was made for the creation of the Gold Star now houses the only Unicameral in the country. Families Memorial. Visit the beautiful black Lincoln is the envy of cities across the USA with our granite monument at Antelope Park. one public school district. We could go on and on. • Supported the release of the latest Lin- We have tackled great challenges and embraced Barbara Bartle Tom Smith coln Vital Signs report at a summit en- marvelous opportunities. President Chair of the Board couraging citizens to “step up” to the P r o s p e r L i n c o l n c o m m u n i t y a g e n d a .