Understanding the Human Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Morning of My Life in China

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com r the MORNING OP MY LIFE IN CHINA. Comprising an Oiti.ixi oi tuk history , /OF FOREIGN INTERCOURSE From the Last Year of the Regime of HONORABLE EAST INDIA COMPANY, 1883 : ' To the Imprisonment of the FOREIGN CO iiiiuNiin IN 1889 BY Gideon Kte, Jr. Corresponding Member of the American Geographical and Statistical Society : Author of Rationale of the China Question, tec, &c. CANTON. 1873. THE MORNING OF MY LIFE IN CHINA. A LECTURE DELIVERED BEFORE THE CANTON COMMUNITY ON THE EVENING OF JANUARY 81st, 1873. by Mr. NYE :— COUNT DE CHAPPEDELAINE, CONSUL OF FRANCE, IN THE CHAIR- COUNT CHAPPEDELAINE :— LADIES AND GENTLEMEN :— I rise to address you with a diffidence that it were vain to dis semble, and which I am sure you will feel is becoming in me, after the learned and at tractive Orations and other classical enter tainments of this brilliant Season. I have not the vigorous grasp of a Sampson,* to " bring down the home:" nor the agile precision of a stripling David, to hit the mark with my pebble : — * Allusion to a Gentleman who had lectured previously with much applause. 540270 2 : •:ifi&3:ie39. How, then, can T find courage to raise my eyes to those of the critical Scholar,* whose opening historical discourse was embellished with the flowers of Poetry ; or expect to rival the interest of the other learned and scientific Lectures, with my feeble periods ? And how much less, can I hope to awaken a responsive chord of sympathy in the hearts of those whose ears were filled with the strains of "God's Alphabet" — (of Music) — so capably rendered to us early in the Season ? It is, therefore, in im plicit reliance upon your indulgence, that in this the fortieth year since I reached Can ton, I obey the command of the Gentleman — to whose initiative we are indebted for these social Assemblages — to contribute my simple mite to the ample offerings of others. -

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: NINA SIMONE, DANCE TGHEATER AND

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: NINA SIMONE, DANCE TGHEATER AND THE SHAPES OF WOMEN Heather Lynn Looney, MFA in Dance, 2009 Thesis directed by: Karen Bradley University of Maryland Dance Department Nina Simone, Dance Theater and the Shapes of Women contains the background, process, involvement and discoveries made during the creation and production of the dance work Morning of My Life. The issues of self value and the process of personal change dealt with in Morning of My Life are brought to light and openly detailed through movement description. This dance work developed from the unique experiences of the choreographer discovering an understanding of femininity through the music of Nina Simone. From an artistic stand point, the creation of this work examined how thoroughly dance communicates to general audiences connecting to art forms in a world of multimedia and sensory overload. NINA SIMONE, DANCE TGHEATER AND THE SHAPES OF WOMEN by Heather Lynn Looney Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts 2009 Advisory Committee: Karen Bradley, Chair Paul Jackson Dr. Barry Pearson Charles Rutherford Foreward I began working on the piece Morning of My Life when I first encountered Nina Simone. The summer of 2000 in North Carolina was melt-your-eyeballs-in-their-sockets- hot. For the six week duration of the American Dance Festival held in Durham, I lived in a fraternity house with seven other dancers and a ferret. The ferret and I became good friends and still write to each other occasionally. -

The Lyric Poetry

HIDDEN TALENT contributions of aboriginal musicians of the new england tablelands to contemporary aboriginal culture and cultural re-vitalisation the lyric poetry peter yanada mckenzie i’ll dance with you ’til the morning my dreams of you are of course gossamer webs I am spinning when we dance the armidale waltz peter mckenzie 2010 1 the lyric poetry of peter mckenzie 2 HIDDEN TALENT Contributions of Aboriginal musicians of the New England Tablelands to Contemporary Aboriginal Culture and Cultural Re-vitalisation Lyrics / Poetry submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Creative Arts University of Western Sydney College of Arts Sydney, Australia December 2010 3 Dedicated to Mavis Mary Elizabeth McKenzie 4 the words: macky 6 the armidale waltz 7 albert koiki and charles 8 bayside mission dreaming 9 tin mansion 10 the killin’ has began 11 brown bag blues 13 coorinna coorinna forever 15 the cotton chipping song 17 davy was a thinker 19 where heaven has gone 21 hey come on 22 koori gals and captains 24 lament for eora 25 mckenzie lament 26 narragundah dreaming 28 north country 29 shine on jesus 30 silent tears 31 tell me robert gregory 33 browlee moon 35 our mingy little mob 36 ballad of a hero 37 nothing man 39 5 macky well mavis mary elizabeth can you hear me pray? when i tell you of your famil-ly and where they are today your eldest travelled ’round the world found art and image-ry your youngest davy died too soon mission by the sea you have a grandson mavis his mother you well know when she came from -

Sheet Music (Unclassified)

SHEET MUSIC (UNCLASSIFIED) A Beautiful Friendship A Touch of the Blues A Certain Smile 'A' Train A Christmas Song A Walkin Miracle A Day in the Life of a Fool A Whistlin' Kettle & a Dancing Cat A Dream is a Wish your Heart Makes A White Sports Coat & a Pink Carnation A Fine Romance A Windmill in Old Amsterdam A Foggy Day A Woman in Love A Garden in the Rain A Wonderful Day like Today A Good Idea Son A Wonderful Guy A Gordon for Me A World of ou Own A Hard Day's Night A You're Adorable A Horse with no Name Abide with Me A Hunting We Will Go Abie my Boy A Kiss in the Dark About a Quarter to Nine A Little bit More AC/DC A Little Bitty Tear Accentuate the Positive A Little Co-operation from you Accordionist A Little Girl from Little Rock Ace of Hearts A Little in Love Across the Alley from the Alamo A Little Kiss Each Morning Across the Alley from the Alamo A Little Love A Little Kiss Across the Great Divide A Little on the Lonely Side Across the Universe A Long & Lasting Love Act Naturally A Loser with nothing to loose Adagio from Sonata Pathetique A Lot of Livin' to Do Addicted to Love A Lovely Way to Spend an Evening Adios A Man & A Woman Adios Amor A Man Chases a Girl Adios Muchachos A Man without Love African Waltz A Marshmallow World After the Ball A Million Miles from Nowhere After the Love has Gone A Night in Tunisia After the Rain A Nightingale Sang in Berkely Square After You've Gone A Paradise for Two Agadoo A Pretty Girl is Like a Melody Again A Rockin' Good Way Agatha Christies Poirot A Root'n Toot'n Santa Claus Ah So Pure A -

Abi Ofarim Musiker Und Produzent Im Gespräch Mit Gabi Toepsch

BR-ONLINE | Das Online-Angebot des Bayerischen Rundfunks Sendung vom 23.4.2010, 20.15 Uhr Abi Ofarim Musiker und Produzent im Gespräch mit Gabi Toepsch Toepsch: Herzlich willkommen zu alpha-Forum. Unser Gast ist heute Abi Ofarim, Musiker und Autor, der Licht und Schatten kennt. Herr Ofarim, schön, dass Sie da sind. Ofarim: Es ist schön, hier zu sein. Toepsch: Die Roaring Sixties waren die Zeit von Esther und Abi Ofarim. "Cinderella Rockefella", "Morning of My Life" u. a.: Das waren die Hits von den beiden. Sie haben die Säle und die Stadien der Welt gefüllt, sind von der Queen empfangen und geehrt worden und haben 59 Goldene Schallplatten überreicht bekommen. Ich glaube, es waren auch noch 14 Platinschallplatten, oder? Ofarim: Ich habe sie nicht gezählt. Toepsch: Sie haben sich dann getrennt und es ist jahrzehntelang still gewesen um Sie beide. Nun sind Sie beide wieder auf der Bühne, allerdings jeder von Ihnen solo. Im Rampenlicht heute bei uns im Studio sitzt Abi Ofarim: Wie ist es denn nach so langer Zeit, wieder im Rampenlicht, auf der Bühne zu stehen? Ofarim: Als mein erster Sohn Gil geboren wurde, habe ich gesagt: "Jetzt keine Konzerte, keine Bühne mehr! Jetzt bin ich Papa und jetzt geht es um Windeln usw.!" Das war 1982 und ich war gerade mit meiner LP "Much too much" herausgekommen. Diese LP wurde die Nummer 1 auf der Bestenliste damals. Als ich dann gesagt habe, dass ich keine Konzerte mehr geben werde, haben alle zu mir gesagt: "Du spinnst doch! Jetzt hast du so lange warten müssen, bis du wieder eine Soloplatte gemacht hast!" Aber, wie gesagt, ich wurde Vater und habe dann jahrelang mit meinen Jungs Musik gemacht. -

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

THE STRANGE CASE OF DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE Robert Louis Stevenson Gothic Digital Series @ UFSC FREE FOR EDUCATION Story of the Door Search for Mr. Hyde Dr. Jekyll was quite at Ease The Carew Murder Case Incident of the Letter Incident of Dr. Lanyon Incident at the Window The Last Night Dr. Lanyon’s Narrative Henry Jekyll’s Full Statement of the Case The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde Robert Louis Stevenson (January, 1886) Story of the Door MR. Utterson the lawyer was a man of a rugged countenance that was never lighted by a smile; cold, scanty and embarrassed in discourse; backward in sentiment; lean, long, dusty, dreary and yet somehow lovable. At friendly meetings, and when the wine was to his taste, something eminently human beaconed from his eye; something indeed which never found its way into his talk, but which spoke not only in these silent symbols of the after-dinner face, but more often and loudly in the acts of his life. He was austere with himself; drank gin when he was alone, to mortify a taste for vintages; and though he enjoyed the theatre, had not crossed the doors of one for twenty years. But he had an approved tolerance for others; sometimes wondering, almost with envy, at the high pressure of spirits involved in their misdeeds; and in any extremity inclined to help rather than to reprove. “I incline to Cain’s heresy,” he used to say quaintly: “I let my brother go to the devil in his own way.” In this character, it was frequently his fortune to be the last reputable acquaintance and the last good influence in the lives of downgoing men. -

Archiving a Life: Post-Shoah Paradoxes of Memory Legacies Leora Auslander

Archiving a Life: Post-Shoah Paradoxes of Memory Legacies Leora Auslander After years of struggle for appropriate acknowledgement and commemora- tion of the Holocaust, as well as for support for teaching, archival collection and research on the topic, the quest for a public presence for the Shoah in Western Europe and the United States has largely been accomplished. That crucial labor has, however, left open, and perhaps to some extent created, another set of questions concerning the relation of the Shoah to European Jewish history as well as that of survivors and their descendants to that experience. Some of these questions are collective and institutional: there is close to consensus in Western Europe that Germany and other European nation- states should preserve the record of the expropriation, exploitation, and murder of the Jews who lived within their borders during the Second World War. Specifically which traces should be kept, by whom, where, and in what form, however, is far more difficult to determine. What documentation, for example, of prewar Jewish life and the annihilation process should archivists in the state’s employ collect and catalogue? Which should be held in Jewish institutions located in Europe, Israel, or the United States? What control can and should survivors and their heirs have over their legacies, over the traces of their lives? What influence should historians have in shaping archival and museum collections? Which narratives should be emphasized in the texts produced from these sources? A striking example of the challenges these questions pose is the struggle over the fate of Pierre Lévi’s suitcase. -

CHRIST on the MOUNTAIN C ATHOLIC C HURCH

CHRIST on the MOUNTAIN C ATHOLIC C HURCH V :. 0VJ%V·:@V1QQR5 R :`1. HV7R R :6%IGV`7R R R:1C7Q HVH.`1 QJ .VIQ%J :1J8Q`$ VG71118H.`1 QJ .VIQ%J :1J8JV Saturday at 4:30 p.m. (Ancipatory) %JR:7: 7 :8I87 :8I8 Q:`7: 7:8I8 %VR:7V`1R:71` : %`R:7 7:8I8 Q:`7GV`Q`VV:H. :: 7:8I8 Eucharisc Adoraon 1` `1R:7Q` .VIQJ . `QI 7V 7]8I8 QJ`V1QJ : %`R:77V7]8I8 HVQ%` 7:8I8V7]8I8 %VR:7V`1R:7 .`1 QJ .V Q%J :1J.%`H.1V_%1]]VR11 . an inducve loop hearing assist system. If you :`V%1J$.V:`1J$:1RRV01V:JR .V7HQJ :1J Christ on the Mountain is a Catholic community of the faithful >Q1C?5]CV:V11 H.7Q%`.V:`1J$RV01HV Q where the faith is lived and passed on; the sacraments are celebrated; >?^VCV].QJV_ Q`VHV10V:%R1Q1$J:C1J .V the Gospel is preached; works of social justice are performed; H.%`H.G%1CR1J$8`7Q%`.V:`1J$RV01HVRQVJQ and the faithful are educated. The parish is, pre-eminently, the HQJ :1J>Q1C?5:@:J%.V` QCQ:J7Q%: means of assuring the faithful, through the sacraments, and especially special receiver that you can use while aending the Eucharist, are spiritually nourished and saved. Mass or other church funcon. F77`G S`31 A 3J`1 J_7 | JY1 7, 2019 Decorating Items Needed for Vacation Bible School! We’re going to jump into our rocket ship and blast off To Are Selling Colorado’s Mars and Beyond where kids Finest Peaches can discover the wonders of God’s universe! Items are The Knights of needed to transform the Columbus will be taking JDM hall into our space travel adventure. -

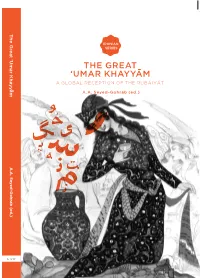

The Great 'Umar Khayyam

The Great ‘Umar Khayyam Great The IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES The Rubáiyát by the Persian poet ‘Umar Khayyam (1048-1131) have been used in contemporary Iran as resistance literature, symbolizing the THE GREAT secularist voice in cultural debates. While Islamic fundamentalists criticize ‘UMAR KHAYYAM Khayyam as an atheist and materialist philosopher who questions God’s creation and the promise of reward or punishment in the hereafter, some A GLOBAL RECEPTION OF THE RUBÁIYÁT secularist intellectuals regard him as an example of a scientist who scrutinizes the mysteries of the universe. Others see him as a spiritual A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) master, a Sufi, who guides people to the truth. This remarkable volume collects eighteen essays on the history of the reception of ‘Umar Khayyam in various literary traditions, exploring how his philosophy of doubt, carpe diem, hedonism, and in vino veritas has inspired generations of poets, novelists, painters, musicians, calligraphers and filmmakers. ‘This is a volume which anybody interested in the field of Persian Studies, or in a study of ‘Umar Khayyam and also Edward Fitzgerald, will welcome with much satisfaction!’ Christine Van Ruymbeke, University of Cambridge Ali-Asghar Seyed-Gohrab is Associate Professor of Persian Literature and Culture at Leiden University. A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) A.A. Seyed-Gohrab WWW.LUP.NL 9 789087 281571 LEIDEN UNIVERSITY PRESS The Great <Umar Khayyæm Iranian Studies Series The Iranian Studies Series publishes high-quality scholarship on various aspects of Iranian civilisation, covering both contemporary and classical cultures of the Persian cultural area. The contemporary Persian-speaking area includes Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Central Asia, while classi- cal societies using Persian as a literary and cultural language were located in Anatolia, Caucasus, Central Asia and the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent. -

Wateraerobics Master by Song 2207 Songs, 5.9 Days, 16.35 GB

Page 1 of 64 wateraerobics master by song 2207 songs, 5.9 days, 16.35 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Act Of Contrition 2:19 Like A Prayer Madonna 2 The Actress Hasn't Learned The… 2:32 Evita [Disc 2] Madonna, Antonio Banderas, Jo… 3 Addicted To Love 5:23 Tina Live In Europe Tina Turner 4 Addicted To Love (Glee Cast Ve… 3:59 Glee: The Music, Tested Glee Cast 5 Adiós, Pampa Mía! 3:08 Tango Julio Iglesias 6 Advice For The Young At Heart 4:55 The Seeds Of Love Tears For Fears 7 Affairs Of The Heart 3:47 Black Moon Emerson, Lake & Palmer 8 After Midnight 3:09 Time Pieces - The Best Of Eric… Eric Clapton 9 Afternoon Delight (Glee Cast Ve… 3:12 Afternoon Delight (Glee Cast Ve… Glee Cast 10 Against All Odds (Take A Look A… 4:14 Cardiomix The Chris Phillips Project 11 Ain't It A Shame 3:37 The Complete Collection And Th… Barry Manilow 12 Ain't It Heavy 4:25 Greatest Hits: The Road Less Tr… Melissa Etheridge 13 Ain't Looking For Love 4:41 Big Ones Loverboy 14 Ain't Nothing Like The Real Thing 2:17 Every Great Motown Hit of Marvi… Marvin Gaye 15 Ain't That Peculiar 3:02 Every Great Motown Hit of Marvi… Marvin Gaye 16 Air (Andante Religioso) from Hol… 6:53 an Evening with Friends Edvard Grieg - Sir Neville Marrin… 17 Alabama Song 3:20 Best Of The Doors [Disc 1] The Doors 18 Alcazar 7:29 Upfront David Sanborn 19 Alena (Jazz) 5:30 Nightowl Gregg Karukas 20 Alive 3:59 Best Of The Bee Gees, Vol. -

School Praise

SCHOOL PRAISE THE LINDSEY PRESS PREFACE URING the seventeen years that have elapsed Dsince the publication of Hymns for School and Home by the Sunday School Association, an enormous advance has been made in Sunday School method. With better grading of departments and classes, and with the introduction of so many new hymns in such collections as School Worship (1926) and Songs of Praise (Enlarged) (1931), it is evident that no mere addition to the former book would meet the need of modern schools. The present book has therefore been compiled by a joint committee of the Religious Educa- tion Department of the General Assembly and the Northern Sunday School Federation ; and it is offered to the schools to meet the need for vigorous, up- lifting, and inspiring hymns for boys and girls. The book is particularly intended for those between eight and sixteen years, since Primary Departments (which do not as a rule use individual hymn-books) make full use of the Rev. Carey Bonner's Child Songs, and because senior classes may prefer to use the adult hymn-book used in their church services. But a small section of primary hymns not to be found in Child Songs has been supplied for the help of Primary Department Leaders, and a section of hymns specially suitable for senior classes is also included. Over each hymn will be found initials indicating the department for which it is chiefly suited, the MADE AND PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN initials used being P (Primary, under 8 years), J BY JARROLD AND SONS LTD. -

Top 500 60Er

Die SWR1 60er Hitparade Platz Titel Interpret 1 Hey jude The Beatles 2 It s now or never Elvis Presley 3 Massachusetts Bee Gees 4 Yesterday The Beatles 5 In the ghetto Elvis Presley 6 San Francisco Scott Mckenzie 7 A whiter shade of pale Procol Harum 8 Mrs. Robinson Simon & Garfunkel 9 Oh pretty woman Roy Orbison 10 Daydream believer The Monkees 11 What a wonderful world Louis Armstrong 12 Downtown Petula Clark 13 She loves you The Beatles 14 Satisfaction The Rolling Stones 15 Strangers in the night Frank Sinatra 16 I want to hold your hand The Beatles 17 Delilah Tom Jones 18 The sun ain t gonna shine anymore Walker Brothers 19 Honky tonk women The Rolling Stones 20 Somethin stupid Nancy Sinatra 21 A hard day s night The Beatles 22 Bad moon rising Creedence Clearwater Revival 23 Good luck charm Elvis Presley 24 These boots are made for walki Nancy Sinatra 25 All you need is love The Beatles 26 Death of a clown Dave Davies 27 Cathy s clown Everly Brothers 28 Do wah diddy diddy Manfred Mann 29 Get off of my cloud The Rolling Stones 30 In the year 2525 Evans Zager 31 Proud mary Creedence Clearwater Revival 32 World Bee Gees 33 Monday, monday The Mamas & the Papas 34 Needles and pins The Searchers 35 Help The Beatles 36 Wooden heart Elvis Presley 37 Yesterday man Chris Andrews 38 The last time The Rolling Stones 39 Siebzehn Jahr, blondes Haar Udo Jürgens 40 Jumping jack flash The Rolling Stones 41 Mr.