Don Juan's Trans-Mediterranean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 01/12/2012 A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra ABB V.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, vol.1 ABB V.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, vol.2 ABB V.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, vol.3 ABB V.4 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Schmidt ABO Above the rim ACC Accepted ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam‟s Rib ADA Adaptation ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes‟ smarter brother, The AEO Aeon Flux AFF Affair to remember, An AFR African Queen, The AFT After the sunset AFT After the wedding AGU Aguirre : the wrath of God AIR Air Force One AIR Air I breathe, The AIR Airplane! AIR Airport : Terminal Pack [Original, 1975, 1977 & 1979] ALA Alamar ALE Alexander‟s ragtime band ALI Ali ALI Alice Adams ALI Alice in Wonderland ALI Alien ALI Alien vs. Predator ALI Alien resurrection ALI3 Alien 3 ALI Alive ALL All about Eve ALL All about Steve ALL series 1 All creatures great and small : complete series 1 ALL series 2 All creatures great and small : complete series 2 ALL series 3 All creatures great and small : complete series 3 *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ALL series 4 All creatures great -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Quentin Couldn't

The Arts and Entertainment Supplement to the Daily Nexus, for April 13th through April 19th. 1995 Quentin couldn't: make it, but we got the inside scoop» on Destiny- Turns on tJie Ftedio from his co-stars Dylan McDermott and Nancy Travis, along with director Jack Bar an. See pages 4A-5A. 2A Thursday, April 13,1993 Daily Nexus bars of cage / you see scars, much ease — thus “Strug results of my rage.” That’s glin’,” tire soul food, hip- another thing about this hop blues, demi-epic of debut album. In Tricky’s the album. (The “epic” Massive and Unparalleled world, everything is a cage, track would probably be without any hope of re the seven-minute exten prieve. Even love is a sti sion of their first single, T ricky posedly one of 'fricky’s landic woman named any of them out from the fling, repressive activity “Aftermath.”) Amid creak M axinquaye nonsense words, sort of Ragga (again, no last scrapyard beats, hip-hop and sex is the violent ing doors, screeching 4th S t Broadway/I gland based around the name of name) and Alison Gold- breaks, soul slides and means of expressing one’s saxes, cocking rifles and his mother. frapp, who was most re thick, dark atm osphere anger. ambulance wails, Tricky This is almost too dense While we’re on names, cently heard on Orbital’s that just oozes out all over Witness “Abbaon Fat mutters like a junkie com a record for one head to Tricky’s real one is Adrian last album. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title On Both Sides of the Atlantic: Re-Visioning Don Juan and Don Quixote in Modern Literature and Film Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/66v5k0qs Author Perez, Karen Patricia Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE On Both Sides of the Atlantic: Re-Visioning Don Juan and Don Quixote in Modern Literature and Film A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Spanish by Karen Patricia Pérez December 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. James A. Parr, Chairperson Dr. David K. Herzberger Dr. Sabine Doran Copyright by Karen Patricia Pérez 2013 The Dissertation of Karen Patricia Pérez is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my committer Chair, Distinguished Professor James A. Parr, an exemplary scholar and researcher, a dedicated mentor, and the most caring and humble individual in this profession whom I have ever met; someone who at our very first meeting showed faith in me, gave me a copy of his edition of the Quixote and welcomed me to UC Riverside. Since that day, with the most sincere interest and unmatched devotedness he has shared his knowledge and wisdom and guided me throughout these years. Without his dedication and guidance, this dissertation would not have been possible. For all of what he has done, I cannot thank him enough. Words fall short to express my deepest feelings of gratitude and affection, Dr. -

Movies and Mental Illness Using Films to Understand Psychopathology 3Rd Revised and Expanded Edition 2010, Xii + 340 Pages ISBN: 978-0-88937-371-6, US $49.00

New Resources for Clinicians Visit www.hogrefe.com for • Free sample chapters • Full tables of contents • Secure online ordering • Examination copies for teachers • Many other titles available Danny Wedding, Mary Ann Boyd, Ryan M. Niemiec NEW EDITION! Movies and Mental Illness Using Films to Understand Psychopathology 3rd revised and expanded edition 2010, xii + 340 pages ISBN: 978-0-88937-371-6, US $49.00 The popular and critically acclaimed teaching tool - movies as an aid to learning about mental illness - has just got even better! Now with even more practical features and expanded contents: full film index, “Authors’ Picks”, sample syllabus, more international films. Films are a powerful medium for teaching students of psychology, social work, medicine, nursing, counseling, and even literature or media studies about mental illness and psychopathology. Movies and Mental Illness, now available in an updated edition, has established a great reputation as an enjoyable and highly memorable supplementary teaching tool for abnormal psychology classes. Written by experienced clinicians and teachers, who are themselves movie aficionados, this book is superb not just for psychology or media studies classes, but also for anyone interested in the portrayal of mental health issues in movies. The core clinical chapters each use a fabricated case history and Mini-Mental State Examination along with synopses and scenes from one or two specific, often well-known “A classic resource and an authoritative guide… Like the very movies it films to explain, teach, and encourage discussion recommends, [this book] is a powerful medium for teaching students, about the most important disorders encountered in engaging patients, and educating the public. -

Pre-0Wned DVD's and Blu-Rays Listed on Dougsmovies.Com 2 Family

Pre-0wned DVD’s and Blu-rays Listed on DougsMovies.com Quality: All movies are in excellent condition unless otherwise noted Price: Most single DVD’s are $3.00. Boxed Sets, Multi-packs and hard to find movies are priced accordingly. Volume Discounts: 12-24 items 10% off / 25-49 items 20% off / 50-99 items 30% off / 100 or more items 35% off Payment: We accept PayPal for online orders. We accept cash only for local pick up orders. Shipping: USPS Media Mail. $3.25 for the first item. Add $0.20 for each additional item. Free pick up in Amelia, OH also available. Orders will ship within 24-48 hours of payment. USPS tracking numbers will be provided. Inventory as of 03/18/2021 TITLE Inventory as of 03/18/2021 Format Price 2 Family Time Movies - Seven Alone / The Missouri Traveler DVD 5.00 3 Docudramas (religious themed) Breaking the DaVinci Code / The Miraculous Mission / The Search for Heaven DVD 6.00 4 Sci-Fi Film Collector’s Set The Sender / The Code Conspiracy / The Invader / Storm Trooper DVD 7.50 4 Family Adventure Film Set Spirit Bear / Sign of the Otter / Spirit of the Eagle / White Fang (Still Sealed) DVD 7.50 8 Mile DVD 3.00 12 Rounds DVD 3.00 20 Leading Men – 24 disc set - 0 full length movies featuring actors from the Golden Age of films – Cary Grant, Fred Astaire, James Stewart, etc DVD 10.00 20 Classic Musicals: Legends of Stage and Screeen 4-Disc Boxed Set DVD 10.00 50 Classic Musicals - 12 Disc Boxed Set in Plastic Case – Over 66 hours Boxed Set DVD 15.00 50 First Dates DVD 3.00 50 Hollywood Legends - 50 Movie Pack - 12 Disc -

Depictions of Mental Disorder in Mainstream American Film 1988-2010 Catherine A

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 2012 Depictions of Mental Disorder in Mainstream American Film 1988-2010 Catherine A. Sherman Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Sherman, C. (2012). Depictions of Mental Disorder in Mainstream American Film 1988-2010 (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1183 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEPICTIONS OF MENTAL DISORDER IN MAINSTREAM AMERICAN FILM FROM 1988-2010 A Dissertation Submitted to the School of Education Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Catherine A. Sherman, M.Ed., M.F.A. December 2012 Copyright by Catherine A. Sherman, M.Ed., M.F.A. 2012 DEPICTIONS OF MENTAL DISORDER IN MAINSTREAM AMERICAN FILM FROM 1988-2010 By Catherine A. Sherman Approved September 25, 2012 ________________________________ ________________________________ Dr. Lisa Lopez Levers Dr. Emma Mosley Professor of Counselor Education and (Committee Member) Supervision and Rev. Francis Philben, C. S. Sp. Endowed Chair in African Studies (Committee Chair) ________________________________ Dr. Jered Kolbert Associate Professor and Program Director of Counselor Education and Supervision (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ Dr. Olga Welch Dr. Tammy Hughes Dean, School of Education Chair, Department of Counseling, Professor of Education Psychology, and Special Education Professor of Education iii ABSTRACT DEPICTIONS OF MENTAL DISORDER IN MAINSTREAM AMERICAN FILM FROM 1988-2010 By Catherine A. -

Re-Visioning Don Juan and Don Quixote in Modern Literature and Film

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE On Both Sides of the Atlantic: Re-Visioning Don Juan and Don Quixote in Modern Literature and Film A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Spanish by Karen Patricia Pérez December 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. James A. Parr, Chairperson Dr. David K. Herzberger Dr. Sabine Doran Copyright by Karen Patricia Pérez 2013 The Dissertation of Karen Patricia Pérez is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my committer Chair, Distinguished Professor James A. Parr, an exemplary scholar and researcher, a dedicated mentor, and the most caring and humble individual in this profession whom I have ever met; someone who at our very first meeting showed faith in me, gave me a copy of his edition of the Quixote and welcomed me to UC Riverside. Since that day, with the most sincere interest and unmatched devotedness he has shared his knowledge and wisdom and guided me throughout these years. Without his dedication and guidance, this dissertation would not have been possible. For all of what he has done, I cannot thank him enough. Words fall short to express my deepest feelings of gratitude and affection, Dr. Parr. I would like to thank my committee members, Distinguished Professor David K. Herzberger and Associate Professor Sabine Doran, whose profound knowledge in their respective fields, lectures, guidance, and advice provided me with the foundation I needed to begin my research. In addition, I would like to thank Distinguished Professor Raymond L. -

A Guide to the Ramón Hernández Tejano Music Collection, 1922-2019

A Guide to the Ramón Hernández Tejano Music Collection, 1922-2019 Collection 141 Descriptive Summary Creator: Ramón Hernández Title: Ramón Hernández Tejano Music Collection Dates: 1922-2019 [Bulk dates, 1985-2019] Abstract: The Ramón Hernández Tejano Music Collection spans from 1922-2019 and is organized into twelve series. The collection documents the history of Tejano, conjunto, and orquesta music predominately in Texas (although musicians from around the world are represented). The bulk of the material relates to musicians’ publicity material, but all aspects of the business of Tejano music, including record labels, media outlets, publications, and events are also well-represented. The costume collection consisting of stage outfits is also of note. Identification: Collection 141 Extent: 253 boxes, plus oversize, framed items, and artifacts (approx. 175 linear feet) Language: English, Spanish, Japanese Repository: The WittliFF Collections, Texas State University Administrative Information Access Restrictions Open for research. Preferred Citation Ramón Hernández Tejano Music Collection, The Wittliff Collections, Texas State University Acquisition Information Purchase, 2017 Processing Information Processed in 2019-2020 by Susannah Broyles, with assistance from Roman Gros and Kyle Trehan. Notes for Researchers The Ramón Hernández Music Recording Collection includes 45s, LPs, audiocassettes, and CDs and is Collection 141b. The contents are included as an appendix to this collection. Some publications have been transferred to the Wittliff’s book collection and are available through the library’s online catalog. Guide to the Ramón Hernández Tejano Music Collection (Collection 141) 2 Ramón Hernández Biographical Notes Ramón Hernández (1940-) became an authority on Tejano music through his work as a journalist, photographer, publicist, collector, and musicologist. -

Human Rights and Spain's Golden Age Theatre: National History

HUMAN RIGHTS AND SPAIN’S GOLDEN AGE THEATRE: NATIONAL HISTORY, EMPIRE, AND GLOBAL TRADE IN TIRSO DE MOLINA'S EL BURLADOR DE SEVILLA Roberto Cantú Abstract: this essay argues one fundamental point: namely, that to understand our current globalized condition, one must first recall and rethink the first globalization of markets, exchanges of ideas, and the migration of peoples across the world’s oceans in the sixteenth century under the flags of Spanish and Portuguese galleons. From this argument the critical task turns to the analysis of Tirso de Molina’s El Burlador de Sevilla (The Trickster of Seville, 1620), a play that represents Spain’s Golden Age in its artistic as well as political and religious dimensions, specifically in its representation of Islamic and Christian conflicts that contain in embryo form questions of religious tolerance and human rights across the globe from the Age of Discovery to the present. This study proposes that Tirso de Molina’s comedias open paths of reflection on sixteenth century forms of European nationalism that coincided with the rise of other imperial nations— English, French, Dutch—and resulted in caste-like hierarchies and religious conflicts in colonial settings, problems that continue to divide peoples across the world. Overshadowed in his time by Spanish playwrights like Lope de Vega (1562-1635) and Pedro Calderón de la Barca (1601-1681), Tirso de Molina was all but forgotten by the end of the eighteenth century. His international impact on drama, music, poetry, film, and in daily discourse has been immense, and yet his creation—Don Juan, the archetypal libertine and seducer—is often assumed to be the leading man in the work of some other playwright, poet, or composer. -

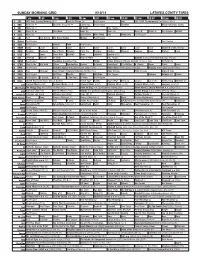

Sunday Morning Grid 8/10/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/10/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Golf 2014 PGA Championship Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Paid Program Triathlon World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Vista L.A. Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Local Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Charlie II (2006, Drama) 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cook Kitchen Lidia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Batman ››› (1989) Jack Nicholson. (PG-13) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Atlas Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Bedtime Stories ›› (2008) Adam Sandler. (PG) Home Alone 4 ›› (2002, Comedia) Stardust ››› (2007) Claire Danes. -

Sandspur, Vol 101 No 21, March 30, 1995

University of Central Florida STARS The Rollins Sandspur Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida 3-30-1995 Sandspur, Vol 101 No 21, March 30, 1995 Rollins College Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rollins Sandspur by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Rollins College, "Sandspur, Vol 101 No 21, March 30, 1995" (1995). The Rollins Sandspur. 41. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/41 Don Juan, Conceits, Letters, Eating and Psycho Disorders, and Evil See FORUM See STYLE 1894 • THE NEWSPAPER OF ROLLINS COLLEGE • 1995 Issue #2: illins College - Winter Park, Fhrida 995 Innovative Firms Mike Porco Share Traits, Says Deposed Rollins Prof Special to the Sandspur Peter Behringer tinue to do so unless those firms become Sandspur Rollins. I just want to get my message Innovative firms share characteris more innovative," Higgins said. "Inno On Tuesday March 28, the Student Hear out to the student body... ultimately I tics that allow them to succeed regard vation is the only long-term sustainable ing Board formally announced its decision have faith in the system to make the less ofthe differences in their cultures, competitive advantage. Businesses that to remove SGA President Mike Porco from right decision." says a Rollins College business pro fail to do so may well find themselves office.