Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Dry Tortugas National Park

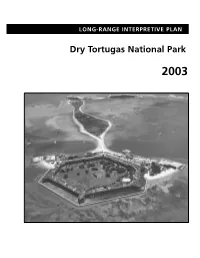

LONG-RANGE INTERPRETIVE PLAN Dry Tortugas National Park 2003 Cover Photograph: Aerial view of Fort Jefferson on Garden Key (fore- ground) and Bush Key (background). COMPREHENSIVE INTERPRETIVE PLAN Dry Tortugas National Park 2003 LONG-RANGE INTERPRETIVE PLAN Dry Tortugas National Park 2003 Prepared by: Department of Interpretive Planning Harpers Ferry Design Center and the Interpretive Staff of Dry Tortugas National Park and Everglades National Park INTRODUCTION About 70 miles west of Key West, Florida, lies a string of seven islands called the Dry Tortugas. These sand and coral reef islands, or keys, along with 100 square miles of shallow waters and shoals that surround them, make up Dry Tortugas National Park. Here, clear views of water and sky extend to the horizon, broken only by an occasional island. Below and above the horizon line are natural and historical treasures that continue to beckon and amaze those visitors who venture here. Warm, clear, shallow, and well-lit waters around these tropical islands provide ideal conditions for coral reefs. Tiny, primitive animals called polyps live in colonies under these waters and form skeletons from cal- cium carbonate which, over centuries, create coral reefs. These reef ecosystems support a wealth of marine life such as sea anemones, sea fans, lobsters, and many other animal and plant species. Throughout these fragile habitats, colorful fishes swim, feed, court, and thrive. Sea turtles−−once so numerous they inspired Spanish explorer Ponce de León to name these islands “Las Tortugas” in 1513−−still live in these waters. Loggerhead and Green sea turtles crawl onto sand beaches here to lay hundreds of eggs. -

Bookletchart™ Intracoastal Waterway – Bahia Honda Key to Sugarloaf Key NOAA Chart 11445

BookletChart™ Intracoastal Waterway – Bahia Honda Key to Sugarloaf Key NOAA Chart 11445 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Published by the The tidal current at the bridge has a velocity of about 1.4 to 1.8 knots. Wind effects modify the current velocity considerably at times; easterly National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration winds tend to increase the northward flow and westerly winds the National Ocean Service southward flow. Overfalls that may swamp a small boat are said to occur Office of Coast Survey near the bridge at times of large tides. (For predictions, see the Tidal Current Tables.) www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov Route.–A route with a reported controlling depth of 8 feet, in July 1975, 888-990-NOAA from the Straits of Florida via the Moser Channel to the Gulf of Mexico is as follows: From a point 0.5 mile 336° from the center of the bridge, What are Nautical Charts? pass 200 yards west of the light on Red Bay Bank, thence 0.4 mile east of the light on Bullard Bank, thence to a position 3 miles west of Northwest Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show Cape of Cape Sable (chart 11431), thence to destination. water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much Bahia Honda Channel (Bahia Honda), 10 miles northwestward of more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and Sombrero Key and between Bahia Honda Key on the east and Scout efficient navigation. -

Keys Sanctuary 25 Years of Marine Preservation National Parks Turn 100 Offbeat Keys Names Florida Keys Sunsets

Keys TravelerThe Magazine Keys Sanctuary 25 Years of Marine Preservation National Parks Turn 100 Offbeat Keys Names Florida Keys Sunsets fla-keys.com Decompresssing at Bahia Honda State Park near Big Pine Key in the Lower Florida Keys. ANDY NEWMAN MARIA NEWMAN Keys Traveler 12 The Magazine Editor Andy Newman Managing Editor 8 4 Carol Shaughnessy ROB O’NEAL ROB Copy Editor Buck Banks Writers Julie Botteri We do! Briana Ciraulo Chloe Lykes TIM GROLLIMUND “Keys Traveler” is published by the Monroe County Tourist Development Contents Council, the official visitor marketing agency for the Florida Keys & Key West. 4 Sanctuary Protects Keys Marine Resources Director 8 Outdoor Art Enriches the Florida Keys Harold Wheeler 9 Epic Keys: Kiteboarding and Wakeboarding Director of Sales Stacey Mitchell 10 That Florida Keys Sunset! Florida Keys & Key West 12 Keys National Parks Join Centennial Celebration Visitor Information www.fla-keys.com 14 Florida Bay is a Must-Do Angling Experience www.fla-keys.co.uk 16 Race Over Water During Key Largo Bridge Run www.fla-keys.de www.fla-keys.it 17 What’s in a Name? In Marathon, Plenty! www.fla-keys.ie 18 Visit Indian and Lignumvitae Keys Splash or Relax at Keys Beaches www.fla-keys.fr New Arts District Enlivens Key West ach of the Florida Keys’ regions, from Key Largo Bahia Honda State Park, located in the Lower Keys www.fla-keys.nl www.fla-keys.be Stroll Back in Time at Crane Point to Key West, features sandy beaches for relaxing, between MMs 36 and 37. The beaches of Bahia Honda Toll-Free in the U.S. -

Dry Tortugas National Park Monroe County, Florida

APPENDIX A: ERRATA 1. Page 63, Commercial Services, second paragraph. Replace the second sentence with the following text: “The number of vessels used in the operation, and arrival and departure patterns at Fort Jefferson, will be determined in the concession contracting process.” Explanation: The number of vessels to be used by the ferry concessionaire, and appropriate arrival and departure patterns, will be determined during the concessions contracting process that will occur during implementation of the Final GMPA/EIS. 2. Page 64, Commercial Services, third paragraph. Change the last word of the fourth sentence from “six” to “twelve.” Explanation: Group size for snorkeling and diving with commercial guides in the research natural area zone will be limited to 12 passengers, rather than 6 passengers. 3. Page 64, Commercial Services, sixth paragraph. Change the fourth sentence to read: “CUA permits will be issued to boat operators for 12-passenger multi-day diving trips.” Explanation: Group size for guided multi-day diving trips by operators with Commercial Use Authorizations will be 12 passengers, rather than 6 passengers. 4. Page 40, Table 1. Ranges of Visitor Use At Specific Locations. Change the last sentence in the box on page 40 to read: “Group size for snorkeling and diving with commercial guides in waters in the research natural area shall be a maximum of 12 passengers, excluding the guide.” Explanation: Clarifies that maximum group size for guided multi-day diving trips in the RNA by operators with Commercial Use Authorizations will be 12 passengers, rather than six passengers. 5. Page 84, Table 4: Summary of Alternative Actions. -

Climate Change and Florida's National Parks

Climate Change and Florida’s National Parks Florida is among the most climate change-threatened states in the United States. Florida’s treasured national parks—spanning the Greater Everglades ecosystem northward into Gulf Islands National Seashore and beyond—are being impacted by our changing climate. Climate change is the greatest threat science-based policies that enhance the Florida’s economy. NPCA’s Sun Coast America’s national parks have ever faced. resilience of our incredible system of region is systematically assessing, through Nearly everything we know and love about national parks. With Florida’s low elevation, research and analysis, the most serious the parks—their plants and animals, rivers national park sites in the state are especially climate impacts threatening national and lakes, beaches, historic structures, susceptible to the threats associated with park landscapes. This regional climate and more—is already under stress from climate change. Sea level rise, changing dispatch thus serves a twofold purpose: to our changing climate. As America’s ocean conditions, and shifting weather shine a light on climate case studies across leading voice for our national parks, patterns are impacting our landscapes. iconic Floridian places, and to share what National Parks Conservation Association All of these climate impacts converge to NPCA’s Sun Coast team is doing to help (NPCA) is at the forefront of efforts to present unprecedented challenges to park address and adapt to climate threats to address climate impacts and promote management, preservation, tourism, and our treasured national park ecosystems. Above: Florida Bay in Everglades National Park ©South Florida Water Management District NATIONAL PARK Rising Sea Levels Threaten THREAT Biodiversity & Cultural Resources While all national park units in Florida Importance, Everglades National Park are threatened by sea level rise, some protects an abundance of biodiversity parks are more vulnerable than others. -

South Florida National Park Sites

National Park Service National Parks and Preserves U.S. Department of the Interior of South Florida Ranger Station Interpretive Trail Bear Island Alligator Alley (Toll Road) Campground Primitive Camping Rest Area, F 75 75 foot access only l o ri Gasoline Lodging and Meals da to Naples N a No Access to/from t i o Alligator Alley n Restrooms Park Area Boundary a 839 l S c Picnic Area e Public Boat Ramp n i SR 29 c T r Marina a il to Naples 837 Big Cypress 837 National Preserve 1 Birdon Road Turner River Road River Turner 41 841 Big Cypress Visitor Center EVERGLADES 41 821 CITY Gulf Coast Visitor Center Tree Snail Hammock Nature Trail Tamiami Trail Krome Ave. MIAMI 41 Loop Road Shark Valley Visitor Center Florida's Turnpike Florida's 1 SW 168th St. Chekika Everglades Biscayne SR 997 National Park National Park HOMESTEAD Boca Chita Key Exit 6 Dante Fascell Pinelands Visitor Center Pa-hay-okee Coe Gulf of Mexico Overlook N. Canal Dr. Visitor (SW 328 St.) Center Elliott Key 9336 Long Pine Key (Palm Dr.) Mahogany 1 Hammock Royal Palm Visitor Center Anhinga Trail Gumbo Limbo Trail West Lake Atlantic Ocean Flamingo Visitor Center Key Largo Fort Jefferson Florida Bay 1 North Dry Tortugas 0 5 10 Kilometers National Park 05 10 Miles 0 2 4 70 miles west of Key West, Note: This map is not a substitute for an Miles by plane or boat only. up-to-date nautical chart or hiking map. Big Cypress, Biscayne, Dry Tortugas, and Everglades Phone Numbers Portions of Biscayne and 95 826 Everglades National Parks National Park Service Website: http://www.nps.gov 95 Florida Turnpike Florida Tamiami Trail Miami Important Phone Numbers 41 41 Shark Valley 826 Visitor Center 1 Below is a list of phone numbers you may need to help plan your trip to the 874 south Florida national parks and preserves. -

Tortugas Ecological Reserve

Strategy for Stewardship Tortugas Ecological Reserve U.S. Department of Commerce DraftSupplemental National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Environmental National Ocean Service ImpactStatement/ Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management DraftSupplemental Marine Sanctuaries Division ManagementPlan EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), working in cooperation with the State of Florida, the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council, and the National Marine Fisheries Service, proposes to establish a 151 square nautical mile “no- take” ecological reserve to protect the critical coral reef ecosystem of the Tortugas, a remote area in the western part of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. The reserve would consist of two sections, Tortugas North and Tortugas South, and would require an expansion of Sanctuary boundaries to protect important coral reef resources in the areas of Sherwood Forest and Riley’s Hump. An ecological reserve in the Tortugas will preserve the richness of species and health of fish stocks in the Tortugas and throughout the Florida Keys, helping to ensure the stability of commercial and recreational fisheries. The reserve will protect important spawning areas for snapper and grouper, as well as valuable deepwater habitat for other commercial species. Restrictions on vessel discharge and anchoring will protect water quality and habitat complexity. The proposed reserve’s geographical isolation will help scientists distinguish between natural and human-caused changes to the coral reef environment. Protecting Ocean Wilderness Creating an ecological reserve in the Tortugas will protect some of the most productive and unique marine resources of the Sanctuary. Because of its remote location 70 miles west of Key West and more than 140 miles from mainland Florida, the Tortugas region has the best water quality in the Sanctuary. -

Biscayne National Park, Florida

National Park Service Biscayne U.S. Department of the Interior Camping Guide to Biscayne National Park Boca Chita Key Tent camping is permitted in designated areas on Elliott and Boca Chita Keys. These islands are accessible by boat only. Camping is limited to fourteen (14) consecutive days or no more than thirty (30) days within a calendar year. Reservations are not accepted. The sites are available on a first-come, first-served basis. No services are available on the islands. Facilities Elliott Key: Freshwater toilets, cold water showers, and drinking water are available. Boca Chita Key: Saltwater toilets are available. Sinks, showers and drinking water are NOT available. Fees There is a $15 per night per campsite camping fee. The fee includes a standard campsite (up to 6 people and 2 tents). If docking a boat overnight, there is a $20 fee that includes one night camping. Group campsites (30 people and 5 tents) are $30 per night on Elliott Key. Group campsite is available by reservation only (305) 230-1144 x 008. Holders of the Interagency Senior or Access passes receive a 50% discount on camping and marina use fees. The fee is paid at the self- service fee station on each island. It is your responsibility to make sure that your fees are paid. NPS rangers will verify payment compliance. Camping/marina use fees must be paid PRIOR to 5 p.m. daily. Anyone who arrives after 5 p.m. must pay camping/ marina use fees immediately upon arrival. Any vessel in the harbor after 5 p.m. -

Media Kit 19 Keys R1

Distribution Great Locations® is everywhere the tourist goes! Distributed annually from over 400 locations, including over 160 resorts, hotels, motels, inns, guest houses and condominiums... Locations Caribbean Club Playa Largo Caribbean Resort Sands of Islamorada Circle K - 102525 Overseas Hwy Port Largo Villas Cheeca Lodge Smuggler’s Cove Marina throughout the Circle K - 106501 Overseas Hwy Rock Reef Resort Chesapeake Resort Sunset Motel Florida Keys Circle K - 99810 Overseas Hwy Seafarer Resort City Hall Cafe Tropical Optical Courtyard Marriott Senor Frijoles GATEWAY Coral Bay Resort Wahoo’s Restaurant Denny’s Snapper’s Restaurant Budget Host Inn Dion’s White Gate Resort Denny’s Latin Cafe - Outdoor Sunset Cove Resort Dade Corner - Indoor & Outdoor Doc’s Diner - Outdoor Drop Anchor Resort Motel Ziggie & Mad Dogs Tower of Pizza - Outdoor Dove Creek Lodge Fishers Inn Dion’s - Florida City Valero LONG KEY Dunkin’ Donuts Florida High Adventure Sea Base Dion’s - Homestead Wells Fargo - Outdoor Edgewater Lodge Florida Bay Club Florida Keys Brewing Co. Econolodge Wendy’s Fiesta Key of America RV Resort Florida City RV Camp & Park Gilbert’s Resort Motel Green Turtle - Outdoor Hampton Inn Lime Tree Bay Resort Floridian Hotel of Homestead TAVERNIER History of Diving Museum Harriet’s Restaurant - Outdoor Outdoor Resorts Golden Corral Atlantic Bay Resort Hungry Tarpon @ Robbies - Outdoor Hidden Out Restaurant Caloosa Cove Resort Holiday Inn Islamorada Chamber of Commerce CONCH KEY Holiday Inn Capt. Slates Dive Center Homestead Visitor Center Islamorada -

Mile Marker 0-65 (Lower Keys)

Key to Map: Map is not to scale Existing Florida Keys Overseas Heritage Trail Aquatic Preserves or Alternate Path Overseas Paddling Trail U.S. 1 Point of Interest U.S. Highway 1 TO MIAMI Kayak/Canoe Launch Site CARD SOUND RD Additional Paths and Lanes TO N KEY LARGO Chamber of Commerce (Future) Trailhead or Rest Area Information Center Key Largo Dagny Johnson Trailhead Mangroves Key Largo Hammock Historic Bridge-Fishing Botanical State Park Islands Historic Bridge Garden Cove MM Mile Marker Rattlesnake Key MM 105 Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Office of Greenways & Trails Florida Keys Overseas Heritage Trail Office: (305) 853-3571 Key Largo Adams Waterway FloridaGreenwaysAndTrails.com El Radabob Key John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park MM 100 Swash Friendship Park Keys Key Largo Community Park Florida Keys Community of Key Largo FLORIDA BAY MM 95 Rodriguez Key Sunset Park Dove Key Overseas Heritage Trail Town of Tavernier Harry Harris Park Burton Drive/Bicycle Lane MM 90 Tavernier Key Plantation Key Tavernier Creek Lignumvitae Key Aquatic Preserve Founders Park ATLANTIC OCEAN Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological State Park MM 85 Snake Creek Long Key Historic Bridge TO UPPER Islamorada, Village of Islands Whale Harbor Channel GULF OF MEXICO KEYS Tom's Harbor Cut Historic Bridge Wayside Rest Area Upper Matecumbe Key Tom's Harbor Channel Historic Bridge MM 80 Dolphin Research Center Lignumvitae Key Botanical State Park Tea Table Key Relief Channel Grassy Key MM 60 Conch Keys Tea Table Channel Grassy Key Rest Area Indian Key -

Biscayne National Park from Proposed South Miami-Dade County Development, and Derivation of Numeric Nutrient Criteria for South Florida Estuaries and Coastal Waters

Ecological Impacts on Biscayne Bay and Biscayne National Park from Proposed South Miami-Dade County Development, and Derivation of Numeric Nutrient Criteria for South Florida Estuaries and Coastal Waters Final Report A report prepared by the Southeast Environmental Research Center of Florida International University for the National Park Service, South Florida Natural Resources Center and the South Florida/Caribbean Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit by Henry O. Briceño, Joseph N. Boyer and Peter Harlem December, 2011 Department of the Interior National Park Service South Florida Natural Resources Center and South Florida/Caribbean Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit Host: University - H5000 – 06- 5040 TASK AGREEMENT NO: COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT NO: EFFECTIVE DATES: J5297-08-0085 H5000-06-0104 3/20/08- 12/31/11 Florida International University Henry O. Briceno, Ph.D. Research Scholar, Principal Investigator Southeast Environmental Research Center 11200 SW 8th St, OE #148, Miami, Florida 33199 Phone: (305) 348-1269; Fax: (305) 348-4096 Email: [email protected] Joseph N. Boyer, Ph.D. Associate Professor, Dept. Earth & Environment Director of SERC Southeast Environmental Research Center 11200 SW 8th St, OE #148, Miami, Florida 33199 Phone: (305) 348-3095; Fax: 305-348-4096 Email: [email protected] National Park Service Joffre Castro, Ph.D. P.E. South Florida Ecosystem Office Everglades National Park 950 N Krome Ave.; 3rd Floor Homestead, Florida 33030, Miami, Florida 33199 Phone: (305) 224-4247 Email: [email protected] DISCLAIMER: Views, statements, findings, conclusions, recommendations and data in this report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect views and policies of the U.S. -

Backcountryplan.Pdf

EXHIBIT A MANAGEMENT AGREEMENT for BACKCOUNTRY PORTIONS of KEY WEST NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE GREAT WHITE HERON NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE and NATIONAL KEY DEER REFUGE Monroe County, Florida SEPTEMBER 1992 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE 75 SPRING STREET, S.W. ATLANTA, GEORGIA 30303 and STATE OF FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES TALLAHASSEE, FLORIDA TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION PART I - BACKGROUND P a g e 1. Purposes for Establishment of the National Wildlife Refuges in the Lower Florida Keys 2. Management Authority 3. Environment 4. Traditional Uses 5. Resources A. General Habitat Characteristics B. Endangered and Threatened Species 6. Administration 7. Land Status 8. Management Activities (1986 - present) 9. Agreements and Permits PART II - RESOURCE PROBLEMS 1. Literature Review: Human disturbance of wildlife A. Overview B. Potential Effects of Human Disturbance on Birds C. Colonially Nesting Waterbirds D. Raptors 2. Special Considerations A. Bald Eagles B. Ospreys C. Magnificent Frigatebirds D. Mangrove Islands 3. Personal Watercraft (jet skis) A. Definitions B. Background C. Numbers D. Distribution E. Problems 4. Airboats 5. Water Skiing 6. Commercial Use 7. Law Enforcement Problems 8. Conflicts Between User Groups 9. Loss of Wilderness Values ii PART III - REFUGE OBJECTIVES AND MANAGEMENT STRATEGY P a g e 1. Refuge Objectives A. Highest Priority B. High Priority C. Moderate Priority 2. Management Strategy PART IV - MANAGEMENT ACTIONS 1. Idle Speed, No Motor, and No Access Buffer Zones A. Overview B. Resources Available/Current Program C. Proposed Management a. Definitions b. Organization c. Signage d. Key West National Wildlife Refuge e. Great White Heron National Wildlife Refuge 2.