Curt Flood and a Triumph of the Show Me Spirit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again?

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again? INTRODUCrION "Baseball is everybody's business."' We have just witnessed the conclusion of perhaps the greatest baseball season in the history of the game. Not one, but two men broke the "unbreakable" record of sixty-one home-runs set by New York Yankee great Roger Maris in 1961;2 four men hit over fifty home-runs, a number that had only been surpassed fifteen times in the past fifty-six years,3 while thirty-three players hit over thirty home runs;4 Barry Bonds became the only player to record 400 home-runs and 400 stolen bases in a career;5 and Alex Rodriguez, a twenty-three-year-old shortstop, joined Bonds and Jose Canseco as one of only three men to have recorded forty home-runs and forty stolen bases in a 6 single season. This was not only an offensive explosion either. A twenty- year-old struck out twenty batters in a game, the record for a nine inning 7 game; a perfect game was pitched;' and Roger Clemens of the Toronto Blue Jays won his unprecedented fifth Cy Young award.9 Also, the Yankees won 1. Flood v. Kuhn, 309 F. Supp. 793, 797 (S.D.N.Y. 1970). 2. Mark McGwire hit 70 home runs and Sammy Sosa hit 66. Frederick C. Klein, There Was More to the Baseball Season Than McGwire, WALL ST. J., Oct. 2, 1998, at W8. 3. McGwire, Sosa, Ken Griffey Jr., and Greg Vaughn did this for the St. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E933 HON

June 27, 2018 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E933 PERSONAL EXPLANATION and would invest billions of dollars in Presi- Famers like Satchel Paige, Jackie Robinson, dent Trump’s unnecessary border wall and Ernie Banks, Willard Brown, and Buck O’Neil. HON. LUIS V. GUTIE´RREZ military technology along the border. The Kansas City Blues and Monarchs lead Kansas City in its original baseball fandom, OF ILLINOIS Overall, the bill would simply dismantle fami- lies, detain innocent immigrants and children eventually resulting in the establishment of the IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES for prolonged, indefinite amounts of time, and city’s first stadium in 1923. Known initially as Wednesday, June 27, 2018 closes our border and walls to people around Muehlebach Field, the stadium is rooted adja- Mr. GUTIE´ RREZ. Mr. Speaker, I was un- the world who are ready to contribute to the cent to the Historic 18th and Vine Jazz Dis- avoidably absent in the House chamber for American dream. trict. This stadium would change hands sev- Roll Call votes 291, 292, 293, 294 and 295 on This is not what America is or has ever eral times; however, in the early 1950’s, a Tuesday, June 26, 2018. Had I been present, been. Our diverse nation was built by immi- wealthy real estate developer purchased the I would have voted Nay on Roll Call votes grants coming here to build for themselves stadium, as well as the Philadelphia Athletics, 291, 292, 294 and 295. I would have voted and their families, along with other commu- with the goal of bringing a major league team Yea on Roll Call vote 293. -

Behindthe Story

The Story Behind the Story Dr. Jonathan LaPook reflects on his 60 Minutes Alzheimer’s Feature SUMMER 2018 MISSION: “TO PROVIDE OPTIMAL CARE AND SERVICES TO INDIVIDUALS LIVING WITH DEMENTIA — AND TO THEIR CAREGIVERS AND FAMILIES — THROUGH MEMBER ORGANIZATIONS DEDICATED TO IMPROVING QUALITY OF LIFE” FEATURES PAGE 2 PAGE 8 PAGE 12 Teammates The Story Behind the 60 Seizures in Individuals Minutes Story with Alzheimer’s PAGE 14 PAGE 16 PAGE 18 Respect Selfless Love The Special Bonds Chairman of the Board The content of this magazine is not intended to Bert E. Brodsky be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of Board of Trustees Publisher a physician or other qualified health provider with Gerald (Jerry) Angowitz, Esq. Alzheimer’s Foundation of America any questions you may have regarding a medical Barry Berg, CPA condition. Never disregard professional medical Luisa Echevarria Editor advice or delay in seeking it because of something Steve Israel Chris Schneider you have read in this magazine. The Alzheimer’s Edward D. Miller Foundation of America makes no representations as Design to the accuracy, completeness, suitability or validity Associate Board Members The Monk Design Group of any of the content included in this magazine, Matthew Didora, Esq. which is provided on an “as is” basis. The Alzheimer’s Arthur Laitman, Esq. Foundation of America does not recommend or CONTACT INFORMATION Judi Marcus endorse any specific tests, physicians, products, Alzheimer’s Foundation of America procedures, opinions or other information that may 322 Eighth Ave., 7th floor President & Chief Executive Officer be mentioned in this magazine. -

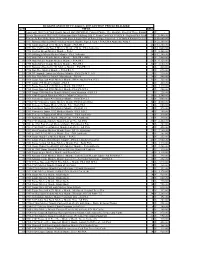

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox Jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds Jersey MLB

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds jersey MLB Wade Boggs Red Sox jersey MLB Johnny Damon Red Sox jersey MLB Goose Gossage Yankees jersey MLB Dwight Goodin Mets jersey MLB Adam LaRoche Pirates jersey MLB Jose Conseco jersey MLB Jeff Montgomery Royals jersey MLB Ned Yost Royals jersey MLB Don Larson Yankees jersey MLB Bruce Sutter Cardinals jersey MLB Salvador Perez All Star Royals jersey MLB Bubba Starling Royals baseball bat MLB Salvador Perez Royals 8x10 framed photo MLB Rolly Fingers 8x10 framed photo MLB Joe Garagiola Cardinals 8x10 framed photo MLB George Kell framed plaque MLB Salvador Perez bobblehead MLB Bob Horner helmet MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Frank White and Willie Wilson framed photo MLB Salvador Perez 2015 Royals World Series poster MLB Bobby Richardson baseball MLB Amos Otis baseball MLB Mel Stottlemyre baseball MLB Rod Gardenhire baseball MLB Steve Garvey baseball MLB Mike Moustakas baseball MLB Heath Bell baseball MLB Danny Duffy baseball MLB Frank White baseball MLB Jack Morris baseball MLB Pete Rose baseball MLB Steve Busby baseball MLB Billy Shantz baseball MLB Carl Erskine baseball MLB Johnny Bench baseball MLB Ned Yost baseball MLB Adam LaRoche baseball MLB Jeff Montgomery baseball MLB Tony Kubek baseball MLB Ralph Terry baseball MLB Cookie Rojas baseball MLB Whitey Ford baseball MLB Andy Pettitte baseball MLB Jorge Posada baseball MLB Garrett Cole baseball MLB Kyle McRae baseball MLB Carlton Fisk baseball MLB Bret Saberhagen baseball -

Major League Baseball and the Antitrust Rules: Where Are We Now???

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL AND THE ANTITRUST RULES: WHERE ARE WE NOW??? Harvey Gilmore, LL.M, J.D.1 INTRODUCTION This essay will attempt to look into the history of professional baseball’s antitrust exemption, which has forever been a source of controversy between players and owners. This essay will trace the genesis of the exemption, its evolution through the years, and come to the conclusion that the exemption will go on ad infinitum. 1) WHAT EXACTLY IS THE SHERMAN ANTITRUST ACT? The Sherman Antitrust Act, 15 U.S.C.A. sec. 1 (as amended), is a federal statute first passed in 1890. The object of the statute was to level the playing field for all businesses, and oppose the prohibitive economic power concentrated in only a few large corporations at that time. The Act provides the following: Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several states, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal. Every person who shall make any contract or engage in any combination or conspiracy hereby declared to be illegal shall be deemed guilty of a felony…2 It is this statute that has provided a thorn in the side of professional baseball players for over a century. Why is this the case? Because the teams that employ the players are exempt from the provisions of the Sherman Act. 1 Professor of Taxation and Business Law, Monroe College, the Bronx, New York. B.S., 1987, Accounting, Hunter College of the City University of New York; M.S., 1990, Taxation, Long Island University; J.D., 1998 Southern New England School of Law; LL.M., 2005, Touro College Jacob D. -

"Latin Players on the Cheap:" Professional Baseball Recruitment in Latin America and the Neocolonialist Tradition Samuel O

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Indiana University Bloomington Maurer School of Law Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 2 Fall 2000 "Latin Players on the Cheap:" Professional Baseball Recruitment in Latin America and the Neocolonialist Tradition Samuel O. Regalado California State University, Stanislaus Follow this and additional works at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Regalado, Samuel O. (2000) ""Latin Players on the Cheap:" Professional Baseball Recruitment in Latin America and the Neocolonialist Tradition," Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls/vol8/iss1/2 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Latin Players on the Cheap:" Professional Baseball Recruitment in Latin America and the Neocolonialist Tradition SAMUEL 0. REGALADO ° INTRODUCTION "Bonuses? Big money promises? Uh-uh. Cambria's carrot was the fame and glory that would come from playing bisbol in the big leagues," wrote Ray Fitzgerald, reflecting on Washington Senators scout Joe Cambria's tactics in recruiting Latino baseball talent from the mid-1930s through the 1950s.' Cambria was the first of many scouts who searched Latin America for inexpensive recruits for their respective ball clubs. -

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

Probable Starting Pitchers 31-31, Home 15-16, Road 16-15

NOTES Great American Ball Park • 100 Joe Nuxhall Way • Cincinnati, OH 45202 • @Reds • @RedsPR • @RedlegsJapan • reds.com 31-31, HOME 15-16, ROAD 16-15 PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS Sunday, June 13, 2021 Sun vs Col: RHP Tony Santillan (ML debut) vs RHP Antonio Senzatela (2-6, 4.62) 700 wlw, bsoh, 1:10et Mon at Mil: RHP Vladimir Gutierrez (2-1, 2.65) vs LHP Eric Lauer (1-2, 4.82) 700 wlw, bsoh, 8:10et Great American Ball Park Tue at Mil: RHP Luis Castillo (2-9, 6.47) vs LHP Brett Anderson (2-4, 4.99) 700 wlw, bsoh, 8:10et Wed at Mil: RHP Tyler Mahle (6-2, 3.56) vs RHP Freddy Peralta (6-1, 2.25) 700 wlw, bsoh, 2:10et • • • • • • • • • • Thu at SD: LHP Wade Miley (6-4, 2.92) vs TBD 700 wlw, bsoh, 10:10et CINCINNATI REDS (31-31) vs Fri at SD: RHP Tony Santillan vs TBD 700 wlw, bsoh, 10:10et Sat at SD: RHP Vladimir Gutierrez vs TBD 700 wlw, FOX, 7:15et COLORADO ROCKIES (25-40) Sun at SD: RHP Luis Castillo vs TBD 700 wlw, bsoh, mlbn, 4:10et TODAY'S GAME: Is Game 3 (2-0) of a 3-game series vs Shelby Cravens' ALL-TIME HITS, REDS CAREER REGULAR SEASON RECORD VS ROCKIES Rockies and Game 6 (3-2) of a 6-game homestand that included a 2-1 1. Pete Rose ..................................... 3,358 All-Time Since 1993: ....................................... 105-108 series loss to the Brewers...tomorrow night at American Family Field, 2. Barry Larkin ................................... 2,340 At Riverfront/Cinergy Field: ................................. -

Major League Baseball in Nineteenth–Century St. Louis

Before They Were Cardinals: Major League Baseball in Nineteenth–Century St. Louis Jon David Cash University of Missouri Press Before They Were Cardinals SportsandAmerican CultureSeries BruceClayton,Editor Before They Were Cardinals Major League Baseball in Nineteenth-Century St. Louis Jon David Cash University of Missouri Press Columbia and London Copyright © 2002 by The Curators of the University of Missouri University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65201 Printed and bound in the United States of America All rights reserved 54321 0605040302 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cash, Jon David. Before they were cardinals : major league baseball in nineteenth-century St. Louis. p. cm.—(Sports and American culture series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8262-1401-0 (alk. paper) 1. Baseball—Missouri—Saint Louis—History—19th century. I. Title: Major league baseball in nineteenth-century St. Louis. II. Title. III. Series. GV863.M82 S253 2002 796.357'09778'669034—dc21 2002024568 ⅜ϱ ™ This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984. Designer: Jennifer Cropp Typesetter: Bookcomp, Inc. Printer and binder: Thomson-Shore, Inc. Typeface: Adobe Caslon This book is dedicated to my family and friends who helped to make it a reality This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix Prologue: Fall Festival xi Introduction: Take Me Out to the Nineteenth-Century Ball Game 1 Part I The Rise and Fall of Major League Baseball in St. Louis, 1875–1877 1. St. Louis versus Chicago 9 2. “Champions of the West” 26 3. The Collapse of the Original Brown Stockings 38 Part II The Resurrection of Major League Baseball in St. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

Baseball Trail 14X8.5.Indd

Whittington Park Clockwise from top: Babe Ruth, Jackie Robinson, Cy Young at Whittington Park, Jackie Robinson. Clockwise from top: Baseball players at Whittington Park, Stan Musial, Honus Wagner. 1 The Eastman Hotel – Hosted many teams in Hot 15 Walter Johnson – Inducted into the Baseball Hall 18 Bathhouse Row – Players would “boil out” in Hot Springs during spring training. Plaque located in the of Fame in 1936. Plaque located on the sidewalk in Springs’ naturally thermal mineral waters to prepare for Hill Wheatley Plaza parking lot (629 Central Avenue). front of the historic Hot Springs High School building the upcoming season. Plaque located on the sidewalk near on Oak Street, between Orange and Olive Streets. the Gangster Museum of America (510 Central Avenue). 2 Buck Ewing – Inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939. Plaque located near the steps 16 Cy Young – Inducted into the National Baseball Hall of 19 Southern & Ohio Clubs – Two of the better known leading to the Rehabilitation Center (105 Reserve Street). Fame in 1937. Plaque located near the ticket windows nightspots frequented by players during spring training. of the Transportation Depot (100 Broadway Terrace). Plaque located on the Ohio Club Building (336 Central Avenue). 3 Dizzy and Daffy Dean – Brothers from Lucas, 17 Tris Speaker – Inducted into the National 20 Happy Hollow – Many legendary players Arkansas, who became the most famous pitching duo in Baseball Hall of Fame in 1937. Plaque located would hike the trails here to prepare for the baseball history. Plaque located on the sidewalk beside at the intersection of Court and Exchange Streets. -

Kit Young's Sale

KIT YOUNG’S SALE #91 1952 ROYAL STARS OF BASEBALL DESSERT PREMIUMS These very scarce 5” x 7” black & white cards were issued as a premium by Royal Desserts in 1952. Each card includes the inscription “To a Royal Fan” along with the player’s facsimile autograph. These are rarely offered and in pretty nice shape. Ewell Blackwell Lou Brissie Al Dark Dom DiMaggio Ferris Fain George Kell Reds Indians Giants Red Sox A’s Tigers EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX EX+ EX+/EX-MT EX+ $55.00 $55.00 $39.00 $120.00 $55.00 $99.00 Stan Musial Andy Pafko Pee Wee Reese Phil Rizzuto Eddie Robinson Ray Scarborough Cardinals Dodgers Dodgers Yankees White Sox Red Sox EX+ EX+ EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT $265.00 $55.00 $175.00 $160.00 $55.00 $55.00 1939-46 SALUTATION EXHIBITS Andy Seminick Dick Sisler Reds Reds EX-MT EX+/EX-MT $55.00 $55.00 We picked up a new grouping of this affordable set. Bob Johnson A’s .................................EX-MT 36.00 Joe Kuhel White Sox ...........................EX-MT 19.95 Luke Appling White Sox (copyright left) .........EX-MT Ernie Lombardi Reds ................................. EX 19.00 $18.00 Marty Marion Cardinals (Exhibit left) .......... EX 11.00 Luke Appling White Sox (copyright right) ........VG-EX Johnny Mize Cardinals (U.S.A. left) ......EX-MT 35.00 19.00 Buck Newsom Tigers ..........................EX-MT 15.00 Lou Boudreau Indians .........................EX-MT 24.00 Howie Pollet Cardinals (U.S.A. right) ............ VG 4.00 Joe DiMaggio Yankees ...........................