East Barnet School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey College Birmingham 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 865/4000 Abbeyfield School Chippenham 803/4000 Abbeywood Community School Bristol 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton-on-Trent 312/5409 Abbotsfield School Uxbridge 894/6906 Abraham Darby Academy Telford 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 825/6015 Akeley Wood Senior School Buckingham 935/4059 Alde Valley School Leiston 919/6003 Aldenham School Borehamwood 891/4117 Alderman White School and Language College Nottingham 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 830/4001 Alfreton Grange Arts College Alfreton 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 340/4615 All Saints Catholic High School Knowsley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College of Arts Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/6907 Appleton Academy Bradford 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 845/4003 ARK William Parker Academy Hastings 371/4021 Armthorpe Academy Doncaster 885/4008 Arrow Vale RSA Academy Redditch 937/5401 Ash Green School Coventry 371/4000 Ash Hill Academy Doncaster 891/4009 Ashfield Comprehensive School Nottingham 801/4030 Ashton -

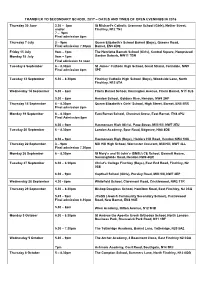

Transfer to Secondary School 2017 – Dates And

TRANSFER TO SECONDARY SCHOOL 2017 – DATES AND TIMES OF OPEN EVENINGS IN 2016 Thursday 30 June 3.30 – 5pm St Michael’s Catholic Grammar School (Girls), Nether Street, and/or Finchley, N12 7NJ 7 – 9pm Final admission 8pm Thursday 7 July 3 – 9pm Queen Elizabeth’s School Barnet (Boys), Queens Road, Final admission 7.30pm Barnet, EN5 4DQ Friday 15 July 9am – 1pm The Henrietta Barnett School (Girls), Central Square, Hampstead Monday 18 July 9am – 1pm Garden Suburb, NW11 7BN Final admission 12 noon Tuesday 6 September 6 – 8.30pm St James’ Catholic High School, Great Strand, Colindale, NW9 Final admission 8pm 5PE Tuesday 13 September 5.30 – 8.30pm Finchley Catholic High School (Boys), Woodside Lane, North Finchley, N12 8TA Wednesday 14 September 5.30 – 8pm Friern Barnet School, Hemington Avenue, Friern Barnet, N11 3LS 5.30 – 8pm Hendon School, Golders Rise, Hendon, NW4 2HP Thursday 15 September 6 – 8.30pm Queen Elizabeth’s Girls’ School, High Street, Barnet, EN5 5RR Final admission 8pm Monday 19 September 6 – 8.30pm East Barnet School, Chestnut Grove, East Barnet, EN4 8PU Final Admission 8pm 6.30 – 9pm Hasmonean High (Girls), Page Street, Mill Hill, NW7 2EU Tuesday 20 September 6 – 8.30pm London Academy, Spur Road, Edgware, HA8 8DE 6.30 – 9pm Hasmonean High (Boys), Holders Hill Road, Hendon NW4 1NA Thursday 22 September 3 – 9pm Mill Hill High School, Worcester Crescent, Mill Hill, NW7 4LL Final admission 7.30pm Monday 26 September 6 – 8.30pm St Mary’s and St John’s (SMSJ) CE School, Bennett House, Sunningfields Road, Hendon NW4 4QR Tuesday 27 -

Why Buy at BEAUFORT PARK?

Why buy at BEAUFORT PARK? YOU’VE ARRIVED | #BeaufortPark #BeaufortPark WHY BUY A HOME FROM ST GEORGE? St George is proud to be part of the U The Berkeley Group are publicly-owned Berkeley Group. For 40 years, the group and listed on the London Stock Exchange as a FTSE 100 company has been committed to the idea of quality U The Berkeley Group has never made – delivering it through hard work, an a loss since first listed on the stock entrepreneurial spirit, attention to detail exchange in 1984 and a passion for good design. U Winner of the Queens Award for Enterprise for Sustainable Development As London’s leading mixed use developer we have a strong presence with the capital and will continue to play a significant role in creating exemplary places that reflect the status, prestige and global importance of our city. YOU’VE ARRIVED Years40 building quality 2 Investor Brochure The 25 acre development is set to There will also be 84,500 sq ft of shops, incorporate more than 3,200 high bars and restaurants with landscaped quality new homes, including Studio, courtyards and parkland to provide Manhattan, 1, 2 and 3 bedroom an exemplar new development for apartments and penthouses. residents, commercial occupiers and the local community. WHY BUY A BEAUFORT PARK? U An established North London residential location U Part of a significant area of regeneration, including over 10,000 new homes, and up to 84,500 sq ft of retail, restaurant and office space U Ease of access to Central London, with 24hr London underground station nearby U Excellent access -

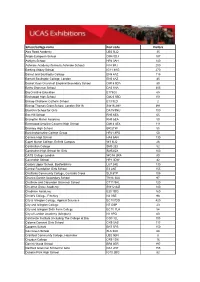

School/College Name Post Code Visitors

School/college name Post code Visitors Alec Reed Academy UB5 5LQ 35 Anglo-European School CM4 0DJ 187 Ashlyns School HP4 3AH 140 Ashmole Academy (formerly Ashmole School) N14 5RJ 200 Barking Abbey School IG11 9AG 270 Barnet and Southgate College EN5 4AZ 115 Barnett Southgate College, London EN5 4AZ 45 Becket Keys Church of England Secondary School CM15 9DA 80 Beths Grammar School DA5 1NA 305 Big Creative Education E175QJ 65 Birchwood High School CM23 5BD 151 Bishop Challoner Catholic School E13 9LD 2 Bishop Thomas Grant School, London SW16 SW16 2HY 391 Blackfen School for Girls DA15 9NU 100 Box Hill School RH5 6EA 65 Brampton Manor Academy RH5 6EA 50 Brentwood Ursuline Convent High School CM14 4EX 111 Bromley High School BR!2TW 55 Buckinghamshire College Group HP21 8PD 50 Canons High School HA8 6AN 130 Capel Manor College, Enfield Campus W3 8LQ 26 Carshalton College SM5 2EJ 52 Carshalton High School for Girls SM52QX 100 CATS College London WC1A 2RA 80 Cavendish School HP1 3DW 42 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE 130 Central Foundation Girls School E3 2AE 155 Chalfonts Community College, Gerrards Cross SL9 8TP 105 Charles Darwin Secondary School TN16 3AU 97 Chatham and Clarendon Grammar School CT11 9AL 120 Chestnut Grove Academy SW12 8JZ 140 Chobham Academy E20 1DQ 160 Christ's College, Finchley N2 0SE 98 City & Islington College, Applied Sciences EC1V7DD 420 City and Islington College N7 OSP 23 City and Islington Sixth Form College EC1V 7LA 54 City of London Academy (Islington) N1 8PQ 60 Colchester Institute (including The College -

Beaufort Park Beaufort Park Amenities

flexible homes for your changing lifestyle DISCOVER THE COLLECTION AT BEAUFORT PARK BEAUFORT PARK AMENITIES Beaufort Park Spa Beaufort Park’s 25 acres of landscaped grounds are a great space for unwinding. Whether you want to take some exercise or relax in the sun, the continental-style courtyards, green space and manicured gardens offer a picturesque setting. Areaworks offers a local workspace where THIS IS MODERN LONDON LIVING people and businesses can work and collaborate. Take advantage of the breakout Discover a neighbourhood designed with the spaces, private offices and coffee shop to modern resident in mind. These contemporary create the working environment you need. 3 bedroom homes complete with private There’s also a fully-equipped gym with new, state-of-the-art cardiovascular machines balconies, and as your priorities change, space for including treadmills, three different types of exercise bikes and a cross trainer. The on-site a home office or nursery, boast exclusive on-site spa complete with a pool, jacuzzi, treatment facilities, landscaped green spaces and convenient room, sauna and steam room, The Spa truly allows you to relax and pamper yourself. connections to the City and West End A run in the local park 3 BEAUFORT PARK EDUCATION & LOCATION MIDDLESEX UNIVERSITY UNIQUE NORTH-WEST LONDON Middlesex is a thriving university located close to Beaufort Park. 19,000 students of 140 different nationalities attend North-West London offers a unique the university, which has won awards for the quality of its combination - a welcoming and teaching, learning and students results. intimate village atmosphere with all HABERDASHERS’ ASKE’S the buzz of the city. -

Monitoring and Review Caseworker Allocations 2021/22

MONITORING & REVIEW CASEWORKER ALLOCATIONS ACADEMIC YEAR 2021/22 Elena Pieretti ([email protected] / Tel: 020 8359 3009/ Mobile: 07710 051 814) School Name Annunciation Catholic Infant (The) School Annunciation RC Junior (The) School Archer Academy (The) Ashmole Primary school Barnfield School Beis Chinuch Beis Soroh Schneirer Beth Jacob Grammar School for Girls Blessed Dominic RC School Edgware Primary School Holy Trinity CE Primary School Jewish Community Secondary School (JCoSS) Menorah Primary School Mount House School St Agnes' RC School St Mary's School (NW3) Special schools Northway Oak Hill School Post 16 Setting Brampton College First Rung London Brookes College Natasha Davis ([email protected] / Tel: 020 8359 6203 | Mobile: 07885210855) School Name All Saints' CE School (N20) Beis Yaakov Girls School Brunswick Park School London Academy Manorside School Menorah Foundation School Menorah High School for Girls Monkfrith School Noam Primary School Osidge School Our Lady of Lourdes RC School Parkfield Primary School Queenswell Infant School Queenswell Junior School St Joseph's Catholic Primary School St Mary's and St John's C of E School St Theresa's RC School Summerside School Totteridge Academy (The) Special schools Oakleigh Post 16 Langdon Samantha Charles ([email protected] / Tel: 020 8359 6238 / Mobile:07707 277159) School Name Alma Primary School Beit Shvidler Primary School Bell Lane Primary School Clowns Nursery Cromer Road School Goodwyn Independent Grimsdell Mill Hill Pre-Prep Mathilda -

Times Parent Power Schools Guide 2020

Times Parent Power Schools Guide 2020 Best Secondary Schools in London London’s grip on the very top of the Parent Power rankings for both state and independent schools has been loosened in the past 12 months. This time last year, the capital had 10 of the top 20 schools in the independent sector and nine of the top 20 state schools — figures that have declined this year to eight and five respectively. The overall number of London schools in both rankings has remained broadly the same, however, (down by just three in both the state and independent sectors) while the southeast region is dominant. The capital encompasses the best and worst of education. London primaries are hugely disproportionately represented in our primary school rankings, published last week, with 181 junior schools in the capital among the top 500. However, too many of the children from these schools go on to get lost in underachieving secondaries that are a million miles — or rather several hundred A*, A and B grades — away from the pages of Parent Power. There is cause for some optimism, however, as recent initiatives begin to bear fruit. New free schools, such as Harris Westminster Sixth Form, are helping to change the educational landscape. Harris Westminster is a partnership between Westminster School, one of the country’s most prestigious independents, and the Harris Federation, which has built up a network of 49 primary and secondary schools across the capital over the past 25 years, sponsored by Lord Harris, who built up the Carpetright empire. Harris Westminster sits fourth in our new ranking of sixth-form colleges, with 41% of students gaining at least AAB in two or more facilitating subjects — those that keep most options open at university, including, maths, English, the sciences, languages, history and geography. -

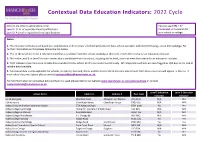

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

A Guide to Secondary Education in Barnet 2011

A guide to secondary education in Barnet 2012 apply online Apply for a school place online at www.eadmissions.org.uk Switch on to the online Common Application Form From 1 September 2011 you can apply for a school place online If your child is due to transfer to a secondary school in September 2012 you need to apply for a school place for them. Use this space to record your username, Why apply online? password and reference number that you have • it speeds up the admission process used to make your application and makes it easier Username • there is no risk that the application will get lost in the post • you can see the result of your application rather than wait for a letter to arrive Password • you can change your application as many times as you like before the closing date • the online system is available 24 hours a day seven days a week up to the closing date of 31 October 2011. After you have submitted your online application, make a note of your application reference number A guide to secondary education in Barnet 2012 3 Message from Councillor Andrew Harper Barnet is very proud of the diversity of its schools, all of which provide an excellent education. Pupils educated in our borough achieve some of the best examination results in the country, both at GCSE and A level. At the same time, local schools provide a wide range of sporting, musical and other activities that give children a rich and broad education. We know that the secondary school application I hope that your child will enjoy his or her time at process can seem daunting and schools and the secondary school and I am sure the education children council together work hard to make the process as receive in Barnet will give them the skills, knowledge smooth as possible. -

Grand Final 2020

GRAND FINAL 2020 Delivered by In partnership with grandfinal.online 1 WELCOME It has been an extraordinary year for everyone. The way that we live, work and learn has changed completely and many of us have faced new challenges – including the young people that are speaking tonight. They have each taken part in Jack Petchey’s “Speak Out” Challenge! – a programme which reaches over 20,000 young people a year. They have had a full day of training in communica�on skills and public speaking and have gone on to win either a Regional Final or Digital Final and earn their place here tonight. Every speaker has an important and inspiring message to share with us, and we are delighted to be able to host them at this virtual event. A message from A message from Sir Jack Petchey CBE Fiona Wilkinson Founder Patron Chair The Jack Petchey Founda�on Speakers Trust Jack Petchey’s “Speak Out” Challenge! At Speakers Trust we believe that helps young people find their voice speaking up is the first step to and gives them the skills and changing the world. Each of the young confidence to make a real difference people speaking tonight has an in the world. I feel inspired by each and every one of them. important message to share with us. Jack Petchey’s “Speak Public speaking is a skill you can use anywhere, whether in a Out” Challenge! has given them the ability and opportunity to classroom, an interview or in the workplace. I am so proud of share this message - and it has given us the opportunity to be all our finalists speaking tonight and of how far you have come. -

CAL 139 2270 Schools Within 400 Metres of London Roads Carrying

CLEAN AIR IN LONDON Schools within 400 metres of roads carrying over 10,000 vehicles per day Received from Transport for London on 060411 List of Schools in Greater London within 400 metres of road link with an All Motor Vehicle Annual Average Daily Flow Estimate of greater than 10,000 Name Address Easting Northing 1 A B C SCHOOL OF ENGLISH A B C SCHOOL OF ENGLISH, 63 NEAL STREET, LONDON, WC2H 9PJ 530,095 181,207 2 ABACUS EARLY LEARNING NURSERY SCHOOL ABACUS EARLY LEARNING NURSERY SCHOOL, 7 DREWSTEAD ROAD, LONDON, SW16 1LY 530,206 172,648 3 ABACUS NURSERY SCHOOL ABACUS NURSERY SCHOOL, LAITWOOD ROAD, LONDON, SW12 9QH 528,997 173,343 4 ABACUS PRE SCHOOL ABACUS PRE SCHOOL, NIGHTINGALE LANE, BROMLEY, BR1 2SB 541,554 169,026 5 ABBEY PRIMARY SCHOOL ABBEY PRIMARY SCHOOL, 137-141 GLASTONBURY ROAD, MORDEN, SM4 6NY 525,466 166,535 6 ABBEY WOOD NURSERY SCHOOL ABBEY WOOD NURSERY SCHOOL, DAHLIA ROAD, LONDON, SE2 0SX 546,762 178,508 7 ABBOTSBURY PRIMARY FIRST SCHOOL ABBOTSBURY PRIMARY FIRST SCHOOL, ABBOTSBURY ROAD, MORDEN, SM4 5JS 525,610 167,776 8 ABBOTSFIELD SCHOOL ABBOTSFIELD SCHOOL, CLIFTON GARDENS, UXBRIDGE, UB10 0EX 507,810 183,194 9 ABERCORN SCHOOL ABERCORN SCHOOL, 28 ABERCORN PLACE, LONDON, NW8 9XP 526,355 183,105 10 ABERCORN SCHOOL ABERCORN SCHOOL, 248 MARYLEBONE ROAD, LONDON, NW1 6JF 527,475 181,859 11 ABERCORN SCHOOL ABERCORN SCHOOL, 7B WYNDHAM PLACE, LONDON, W1H 1PN 527,664 181,685 12 ABINGDON HOUSE SCHOOL ABINGDON HOUSE SCHOOL, 4-6 ABINGDON ROAD, LONDON, W8 6AF 525,233 179,330 13 ACLAND BURGHLEY SCHOOL ACLAND BURGHLEY SCHOOL, 93 BURGHLEY -

Appendix C Hendon Parliamentary Constituency Polling Places Proposals Overview

Appendix C Hendon Parliamentary Constituency Polling Places Proposals Overview: Polling Ward Current Polling Place Proposal District 1 Hale HOA Fairway Primary School No Change 2 Hale HOB Courtland JMI School No Change Move one station (or poss. two) 3 Hale HOC Deansbrook School to new PD (HOF) 4 Hale HOD Portable – Harvester Car Park No Change 5 Hale HOE The Royal British Legion No Change Create Polling Place at 6 Hale HOF None Annunciation Catholic School 7 Mill Hill HPA Etz Chaim Jewish School No Change 8 Mill Hill HPB St Paul’s Church Hall No Change Portable Offices Move to: 9 Mill Hill HPC Waitrose Car Park Portable Offices - Bittacy Road 10 Mill Hill HPD Dollis Infants School No Change 11 Mill Hill HPE Mill Hill Library No Change 12 Hendon HQA Sunnyfields School No Change Move to: 13 Hendon HQB Hendon Library St Mary and St John CE School 14 Hendon HQC Bell Lane School No Change 15 Hendon HQD Hendon School No Change 16 West Hendon HRA Barnet Multi-Cultural Centre No Change 17 West Hendon HRB Hasmonean Primary School No Change 18 West Hendon HRC Parkfield Primary School No Change 19 West Hendon HRD West Hendon Community Centre No Change 20 West Hendon HRE The Hyde school No Change 21 Colindale HSA St Augustine’s Church Hall No Change Grahame Park Community Move one station to new PD 22 Colindale HSB Centre (HSD) Create Polling Place at Estate 23 Colindale HSD None Management Suite The Hyde United Reform Church 24 Colindale HSC No Change Hall 25 Burnt Oak HTA Trinity Watling Church Hall No Change Our Lady of the Annunciation 26 Burnt Oak HTB No Change Church Hall Move to: 27 Burnt Oak HTC Barnfield School St Alphage Church Hall 28 Burnt Oak HTD Watling Community Association No Change 29 Edgware HUA Broadfields Infant School No Change 30 Edgware HUB Edgware Parish Hall Move to Edgware Library 31 Edgware HUC St Peter’s Church Hall No Change Maps reproduced by permission of Geographers' A-Z Map Co.