The High Ross Dam/Skagit River Controversy: the Use of Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flooding the Border: Development, Politics, and Environmental Controversy in the Canadian-U.S

FLOODING THE BORDER: DEVELOPMENT, POLITICS, AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROVERSY IN THE CANADIAN-U.S. SKAGIT VALLEY by Philip Van Huizen A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) June 2013 © Philip Van Huizen, 2013 Abstract This dissertation is a case study of the 1926 to 1984 High Ross Dam Controversy, one of the longest cross-border disputes between Canada and the United States. The controversy can be divided into two parts. The first, which lasted until the early 1960s, revolved around Seattle’s attempts to build the High Ross Dam and flood nearly twenty kilometres into British Columbia’s Skagit River Valley. British Columbia favoured Seattle’s plan but competing priorities repeatedly delayed the province’s agreement. The city was forced to build a lower, 540-foot version of the Ross Dam instead, to the immense frustration of Seattle officials. British Columbia eventually agreed to let Seattle raise the Ross Dam by 122.5 feet in 1967. Following the agreement, however, activists from Vancouver and Seattle, joined later by the Upper Skagit, Sauk-Suiattle, and Swinomish Tribal Communities in Washington, organized a massive environmental protest against the plan, causing a second phase of controversy that lasted into the 1980s. Canadian and U.S. diplomats and politicians finally resolved the dispute with the 1984 Skagit River Treaty. British Columbia agreed to sell Seattle power produced in other areas of the province, which, ironically, required raising a different dam on the Pend d’Oreille River in exchange for not raising the Ross Dam. -

The Skagit-High Ross Controversy: Negotiation and Settlement

Volume 26 Issue 2 U.S. - Canada Transboundary Resource Issues Spring 1986 The Skagit-High Ross Controversy: Negotiation and Settlement Jackie Krolopp Kirn Marion E. Marts Recommended Citation Jackie K. Kirn & Marion E. Marts, The Skagit-High Ross Controversy: Negotiation and Settlement, 26 Nat. Resources J. 261 (1986). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nrj/vol26/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Resources Journal by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. JACKIE KROLOPP KIRN* and MARION E. MARTS** The Skagit-High Ross Controversy: Negotiation and Settlement SETTING AND BACKGROUND The Skagit River is a short but powerful stream which rises in the mountains of southwestern British Columbia, cuts through the northern Cascades in a spectacular and once-remote mountain gorge, and empties into Puget Sound approximately sixty miles north of Seattle. The beautiful mountain scenery of the heavily glaciated north Cascades was formally recognized in the United States by the creation of the North Cascades National Park and the Ross Lake National Recreation Area in 1968, and earlier in British Columbia by creation of the E.C. Manning Provincial Park. The Ross Lake Recreation Area covers the narrow valley of the upper Skagit River in Washington and portions of several tributary valleys. It was created as a political and, to environmentalists who wanted national park status for the entire area, controversial, compromise which accom- modated the city of Seattle's Skagit River Project and the then-planned North Cascades Highway. -

National Register of Historic Places Hydroeiectirc Projects Continuation Sheet

NPS Form 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-O018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service skagit ^VQT & Newhalem Creek National Register of Historic Places Hydroeiectirc Projects Continuation Sheet Section number ___ Page ___ SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 96000416 Date Listed: 4/26/96 Skagit River & Newhalem Creek Hvdroelectirc Projects Whatcom WA Property Name County State Hydroelectric Power Plant MPS Multiple Name This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. Signature of tty^Keejifer Date of Action Amended Items in Nomination: Photographs: The SHPO has verified that the 1989 photographs accurately document the current condition and integrity of the nominated resources. Historic Photos #1-26 are provided as photocopy duplications. Resource Count: The resource count is revised to read: Contributing Noncontributing 21 6 buildings 2 - sites 5 6 structures 1 - objects 29 12 total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register 16 . A revised inventory list is appended to clarify the resource count and contributing status of properties in the district, particularly at the powerplant/dam sites. (See attached) This information was confirmed with Lauren McCroskey of the WA SHPO. DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NFS Form 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Skagit River & Newhalem Creek National Register of Historic Places Hydroelectirc Projects Continuation Sheet Section number The following is a list of the contributing and noncontributing resources within the district, beginning at its westernmost—downstream—end, organized according to geographic location. -

The Damnation of a Dam : the High Ross Dam Controversy

THE DAMYIATION OF A DAM: TIIE HIGH ROSS DAM CONTROVERSY TERRY ALLAN SIblMONS A. B., University of California, Santa Cruz, 1968 A THESIS SUBIUTTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Geography SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY May 1974 All rights reserved. This thesis may not b? reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Terry Allan Simmons Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: The Damnation of a Dam: The High Ross Dam Controversy Examining Committee: Chairman: F. F. Cunningham 4 E.. Gibson Seni Supervisor / /( L. J. Evendon / I. K. Fox ernal Examiner Professor School of Community and Regional Planning University of British Columbia PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University rhe righc to lcnd my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed ' without my written permission. Title of' ~hesis /mqqmkm: The Damnation nf a nam. ~m -Author: / " (signature ) Terrv A. S.imrnonze (name ) July 22, 1974 (date) ABSTRACT In 1967, after nearly fifty years of preparation, inter- national negotiations concerning the construction of the High Ross Dan1 on the Skagit River were concluded between the Province of British Columbia and the City of Seattle. -

The Wild Cascades

THE WILD CASCADES December 1969-January 1970 2 THE WILD CASCADES JXTOR/rH CASCADE3S TJTSTDIEiR. AT1 T_As.C> Je^ BATTLE LINES DRAWN by The Kerosene Kid duty it should have been to protect the park. Each such campaign has been accompanied by barrages of propaganda that the resources of the park were essential to the continued growth of the surrounding area or that new roads were needed along the wilderness beach or across the park's wilderness core "to open it up for the peepul. " Each time the friends of Olympic have rallied, mounted counter-attacks and saved the park. We have no reason to believe the history of the North Cascades over the next third of a century will be any different. But, to para phrase Mr. Churchill, the North Cascades Conservation Council (N3C) was not organized to preside over the dissolution of the North Cascades. We expect attacks and we confi dently expect to win. To prevent Seattle City Light from imple menting its destructive proposals in the Ross Lake National Recreation Area will require as If any conservationist felt he was honor tough a fight as conservationists ever have ably discharged from the wars upon passage waged. The nature of the adversary contrib of the 1968 North Cascades Act, he lacked utes to the difficulty of the battle. Seattle City knowledge of the history of the American Light is no ordinary despoiler of wilderness. National Park system. He may have said to In fact, it's hard to say just what Seattle City himself, "Whew! I'm glad that's over. -

THE WILD CASCADES October - November 1970 2 the WILD CASCADES

'Ha, Ha, Ha . And Not a Cloud in Sight' THE WILD CASCADES October - November 1970 2 THE WILD CASCADES SEATTLE PASSES THE ROSS DAM BUCK! Conservationists have tried for over a year to open the Seattle City Council's eyes to the fact that Seattle City Light has presented a very biased, one-sided story on the raising of Ross Dam. We have had to lobby the City Council and the Mayor from without the walls of City Hall while John Nelson has done his lobbying from within. A year ago the Seattle City Council voted 5 to 4 against the environment by authorizing City Light to proceed with its Ross High Dam plans. Today, one year and one Council election later, the vote was 6 to 2, still against the environment and now making it mandatory that City Light apply to the Federal Power Commission for permission to raise Ross Dam. It might have been 6 to 3 if Sam Smith had been present. (1) On December 19, 1970 Seattle City Light filed its Ross High Dam application with the F. P. C. (2) Immediately the North Cascades Conservation Council also filed with the F. P. C. , but in opposition to City Light's application. (3) The Federal Power Commission will hold hearings on High Ross in 1971 and 1972, possibly in Seattle (we shall let you know). (4) Washington State Department of Ecology will hold public hearings on raising Ross Dam (see page 36). (5) The Canadian Federal Government will conduct judicial hearings on the flooding of the upper Skagit by High Ross (see page 36). -

Water Power License Fees

Chelan River Hydroelectric Facility on Chelan River Report to the Legislature on Water Power License Fees Expenditures, Recommendations, Accountability, and Recognition June, 2020 Publication no. 20-10-027 Publication and Contact Information This report is available on the Department of Ecology’s website at https://fortress.wa.gov/ecy/publications/SummaryPages/2010027.html For more information contact: Water Quality Program P.O. Box 47600 Olympia, WA 98504-7600 Phone: 360-407-6600 Washington State Department of Ecology www.ecy.wa.gov Headquarters, Olympia 360-407-6000 Northwest Regional Office, Bellevue 425-649-7000 Southwest Regional Office, Olympia 360-407-6300 Central Regional Office, Union Gap 509-575-2490 Eastern Regional Office, Spokane 509-329-3400 ADA Accessibility The Department of Ecology is committed to providing people with disabilities access to information and services by meeting or exceeding the requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), Section 504 and 508 of the Rehabilitation Act, and Washington State Policy #188. To request an ADA accommodation, contact Ecology by phone at 360-407-6600 or email at [email protected]. For Washington Relay Service or TTY call 711 or 877-833-6341. Visit Ecology’s website for more information. Publication 20-10-027 June 2020 i Report to the Legislature on Water Power License Fees Expenditures, Recommendations, Accountability, and Recognition by Water Quality Program Washington State Department of Ecology Water Quality Program Washington State Department of Ecology Olympia, -

North Cascades National Park Plan

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Business Management Group North Cascades National Park 2012 Business Plan Produced by Sunrise at Copper Lookout. National Park Service Business Management Group Table of Contents U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, DC 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Spring 2012 2 INTRODUCTION National Park Business Plan Process 2 Letter from the Superintendent 3 Introduction to North Cascades National Park The purpose of business planning in the National Park Service (NPS) is to improve the ability of parks to more clearly 4 PARK OVERVIEW communicate their financial and operational status to principal 4 Orientation stakeholders. A business plan answers such questions as: What 5 Mission and Foundation is the business of this park unit? What are its priorities over 6 Resources the next five years? How will the park allocate its resources to 7 Visitor Information achieve these goals? 8 Personnel 9 Volunteers The business planning process is undertaken to accomplish three 10 Partnerships main tasks. First, it presents a clear, detailed picture of the state 12 Strategic Goals of park operations and priorities. Second, it outlines the park’s 14 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW financial projections and specific strategies the park may employ to marshal additional resources to apply toward its operational 14 Funding Sources and Expenditures needs. Finally, it provides the park with a synopsis of its funding 15 Division Allocations sources and expenditures. 16 DIVISION OVERVIEWS 16 Facility Management 18 Resource Management -

A Timeline of Events in the Upper Skagit

A TIMELINE OF EVENTS IN THE UPPER SKAGIT We tend to develop a natural connection to places in the wild Upper Skagit. Place is also about history and the people who came before us and their relationship to the land. The chronology below is offered here as means to place Upper Skagit peoples, past and present, within a timeline of natural and cultural events, so that we may better consider our own relationships with the land. SOME PRE-CONTACT PERIOD EVENTS (DATED IN YEARS BEFORE PRESENT BY RADIOCARBON TECHNIQUE) 24–18,000 A glacial lake occupies the valley where today’s Ross Lake now exists. 14,500 The large Cordilleran Ice Sheet that covers the northern half of today’s Washington, including the North Cascades (and Seattle and Puget Sound as far south as Centralia), begins to melt away. ca. 11,000 The ice age elephants (mammoths and mastodons) and Bison, prior to this time fairly abundant in many parts of the unglaciated Pacific Northwest, have become extinct. +9000 Earliest evidence of people in the high elevations of Washington State & B.C, & the N. Cascades interior at Cascade Pass, & of the use of Hozomeen chert (a variety of quartz rock similar to flint, used to make tools). 8400 Native people begin a long tradition in the Upper Skagit to quarry Hozomeen chert; parts of Jack, Desolation, & Hozomeen mountain are made of these ancient sea-floor rocks; Hozomeen chert use begins to spread beyond the local source areas. 6000 Cooler moister climate begins, widespread economic shift to more intensive use of local resources, more complex and diverse technologies, along with more permanent villages. -

Skagit Hydroelectric Facility Low Impact Hydropower Review Recertification Report 2017

Skagit Hydroelectric Facility Low Impact Hydropower Review Recertification Report 2017 Prepared by: Peter Drown, President Cleantech Analytics LLC October 12, 2017 Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 3 II. PROJECT LOCATION AND SITE CHARACTERISTICS .................................................................... 5 III. PROJECT WORKS .............................................................................................................................. 7 IV. REGULATORY STATUS ................................................................................................................... 11 V. COMPLIANCE WITH LIHI STANDARDS ........................................................................................ 13 VI. PUBLIC COMMENTS RECEIVED ..................................................................................................... 44 VII. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATION ................................................................................... 44 APPENDIX A AGENCY COMMUNICATIONS ...................................................................................... 45 Table of Figures Figure 1 – Skagit Watershed Locations .......................................................................................................................... 5 Figure 2 – Skagit River & Dam........................................................................................................................................... -

Skagit River Dam Failure Inundation Study

SKAGIT RIVER DAM FAILURE INUNDATION STUDY ..~ Hydrocomp __ ._ __._.__ ._.~" ...---r-- SKAGIT RIVER r DAM FAILURE INUNDATION STUDY C,.. -. ~~: •.< Prepared for City of Seattle - Department of Lighting 1015 Third Avenue Seattle Washington 98104 by Steven M. Thurin, P.E. I- I L Hydrocomp, Inc. 201 San Antonio Circle, Suite 280 Mountain View, California 94040 December, 1981 ~ .. " .. ~'. LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page Dam Failure Study Area •.•.•..••..•.•••...••......•. 6 Gorge Dam Failure (Outflow) •••.•••••..•.•••..•••.•. 28 Gorge Dam Failure (Water Surface Elevation) ...•...• 29 Skagit Routing: Gorge Dam Failure (Flow) ..•....••.. 30 Skagit Routing: Gorge Dam Failure (Water Sur face Elevation) . 31 Diablo Dam Failure (Outflow) •••.••••......•.•••.•.• 33 Diablo Dam Failure (Water Surface Elevation) 34 Gorge Overtopped by Diable Failure (Water Surface Elevation) . 36 Gorge Overtopped by Diablo Failure (Flow) 37 Skagit Routing: Diablo Dam Failure (Flow) 39 Skagit Routing: Diablo Dam Failure (Water Surface Elevation) . 40 Ross Dam Failure (Outflow) ••.••.••••....•••.•..•... 42 Ross Dam Failure (Water Surface Elevation) ••••.•.•. 43 Overtopping Failure of Diablo (Flow) .•.......•••••• 44 Diablo Overtopped by Ross Failure (Water Surface Elevation) . 45 Gorge Overtopped by Ross Failure (Flow) .•...••...•. 46 Gorge Overtopped by Ross Failure (Water Surface Elevation) . 47 5-17 Skagit Routing: Ross Dam Failure (Flow) 48 5-18 Skagit Routing: Ross Dam Failure (Water Surface Elevation) 49 5-19 Skagit Routing: Ross Dam Failure (Water Surface Elevation) 50 6-1 Skagit River Development Dam Failure Inundation M'ap ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 54 it LIST OF TABLES Table Page 1-1 Simulation Results at Marblemount, Concrete and Sedro-Wooley .•..••••....•.•..••...•..•..•.• 3 6-1 Peak Flows and Elevations •••••••••••••••••••••• 52 6-2 Time to Exceed Zero Damage Flow Level ••••••••• 53 , . -

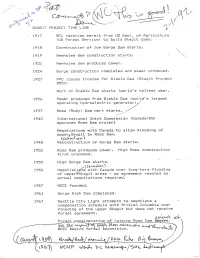

4 SKAGIT PROJECT TIME LINE 1917 191S 1919 1 -7 1924 ,937 1942 I94

•4 f SKAGIT PROJECT TIME LINE 1917 ScL receivea oermit -From US Deot= oi- Aqriculturs (US Forest Service) to build Skagit .dams. 191S Construction of low Gorge Dam starts. 1919 Newhalem dam construction starts. 1 -7 Newhalem dam produces power. 1924 Gorge construction completed and power produced. FPC issues license for Diablo Dam (Skagit Project #553) Work on Diablo Bam starts (world-'s tallest dam). Power prcdiuced from Diablo Dam (world's largest ope rat i nq hydroelsctr'i c generator > ,937 Roes (Ruby) Dam work starts. 1942 International Joint Coimmission (Canada/US) approves Ross Dam project Negotiations with Canada to allcw flooding of upper^ Skag i t by Ross Dam. (CAVNA J \o.r\ i94£ Reconstruction of Gorge Dam starts. Ross Dam produces power. High Ross construction f1rst p reposed, 1953 High Go r g s Dam starts. 1954 Canada over long—term flooding: of Lipperl^Skaqit areas — no agreement reached so annual negotiations r e q u i r e d. 1957 NCCC founded. 1961 Gorge High Dam completed. 1967 Seattle City Light attempts to negotiate a compensation schedule with British Columbia over flocding of the upper Skagit but does not receive forma1 agreement. Form5J__C£iilsideration of raisinq Ross Dam ba-gi no-. Hfl- tiU WpoZc^=^E^n^^5Tl R<hnTAjH>feAA3^ J JL '~\ NCCC begins formal ibpgosition. ^ "^o^eLO^ j WCNJP V>J&^ i:)(3 WJUXAA^^^/^CL is^\t A^ North Cascades National Park and Ross Lake Nat i Q na1 Rec reat ion Area estab1i s bed i o F-!un Duu ka.q iti SDD11 erS (KQ3S) fcunded> ROSS and Province of BC opposition increases.