TO: Eileen Donoghue, City Manager FROM: R. Eric Slagle, Director Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kilburn Lane, North Kensington, W9 £235 Per Week (£1,021 Pcm)

Camden 3 Parkway London NW1 7PG Tel: 020 7482 1060 [email protected] Kilburn Lane, North Kensington, W9 £235 per week (£1,021 pcm) Studio, 1 Bathroom Preliminary Details We are pleased to offer this fantastic self contained modern studio apartment that is on the first floor of a recently developed building. The apartment consists of a good sized studio room along with a separate kitchen and modern bathroom. Its location is fantastic for transport links with the Overground allowing for fast and easy access to Euston station and the Bakerloo line offering connections to the rest London. It has been renovated to a modern standard with neutral decor throughout and a modern bathroom and kitchen. The apartment also has the added bonus of having all of the utility bills bar hot water included within the rent. Key Features • Self contained studio apartment • Some bills included • Separate kitchen • Recently refurbished • Great transport links • Close to local amenities Camden | 3 Parkway, London, NW1 7PG | Tel: 020 7482 1060 | [email protected] 1 Area Overview North Kensington is the key neighbourhood of Notting Hill, the infamous setting for the Notting Hill Carnival, the largest street festival in Europe and an annual spectacle of food, music, costume and colourful sights celebrating Afro- Caribbean cultures and traditions. One of the most cosmopolitan areas of London, it boasts the largest Moroccan population in England and is the site for Trellick Tower, the iconic 31 storey block of flats designed by Erno Goldfinger. A popular destination for an array of people, the property here is incredibly sought after. -

The GW Law Student's Housing Guide

The GW Law Student’s Housing Guide: Created by Students for Students A publication of the GW Law Student Ambassadors The George Washington University Law School Washington, D.C. Table of Contents WASHINGTON, D.C. Foggy Bottom and the Surrounding Area ..............................................................4 Adams Morgan ...........................................................................................................18 Capitol Hill ...................................................................................................................19 Cleveland Park/Woodley Park ................................................................................20 Columbia Heights .....................................................................................................21 Downtown ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������22 Dupont Circle �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������23 Georgetown ...............................................................................................................24 Logan Circle ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������25 Tenleytown/American University ............................................................................26 U Street �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������27 Van Ness ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������28 -

Quarterly Pipeline of Residential Projects in the City of Santa Cruz

Quarterly Pipeline of Residential Projects in the City of Santa Cruz, April 1- June 30,2015 Building Permit Applications Submitted 4-1-2015 through 6-30-2015 PERMIT PERMIT PERMIT STATUS SITE APN SITE ADDRESS DESCRIPTION NUMBER TYPE SUBTYPE BLDG UNDER Split apartment unit, new deck over existing carport, to be B15-0070 REMODEL 005-291-13 809 RIVERSIDE AVE COMMERCIAL REVIEW new apartment D BLDG NEW SINGLE Construct a new 2 story 2,359 sq. ft. condition space with B15-0142 ISSUED 011-162-19 208 BRONSON ST RESIDENTIAL FAMILY 510 sq. ft. garage and 20 sq. ft. porch BLDG Remodel existing two story structure to create a conforming B15-0154 ADDITION ISSUED 011-071-14 816 HANOVER ST RESIDENTIAL 799 sq. ft. ADU BLDG UNDER B15-0188 004-033-04 104 MYRTLE ST Construct a single story 628 sq. ft. SFD RESIDENTIAL REVIEW BLDG NEW SINGLE UNDER Construct a new 2 story 1,902 sq. ft. SFD (heated) and 418 B15-0189 004-033-04 108 MYRTLE ST RESIDENTIAL FAMILY REVIEW sq. ft. garage BLDG NEW ADU UNDER B15-0190 004-244-29 404 WEST CLIFF DR Convert existing heated space to ADU and add balcony RESIDENTIAL ATTACHED REVIEW BLDG NEW ADU UNDER New 2,321 sq. ft. single family dwelling with attached ADU B15-0202 004-232-23 229 BAY ST RESIDENTIAL ATTACHED REVIEW and garage. BLDG NEW SFD DET UNDER B15-0214 006-121-30 1502 LAUREL ST Legalize garage into a 500 sq. ft. ADU RESIDENTIAL ADU REVIEW BLDG NEW ADU B15-0218 APPROVED 002-321-21 180 YOSEMITE ST New attached 375 sq. -

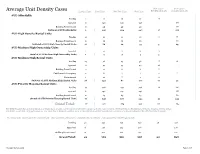

Average Unit Density Cases

New Units - New Units - Average Unit Density Cases Existing Units Total Units Net New Units New Units Residential Zones Commercial Zones AUD Affordable Pending 1 17 16 17 17 Approved 0 148 148 148 148 Building Permit Issued 0 40 40 40 40 Subtotal of AUD Affordable 1 205 204 205 17 188 AUD High Density Rental Units Pending 10 41 31 40 9 31 Building Permit Issued 0 33 33 33 33 Subtotal of AUD High Density Rental Units 10 74 64 73 9 64 AUD Medium High Ownership Units Approved 1 4 3 3 3 Subtotal of AUD Medium High Ownership Units 1 4 3 3 3 AUD Medium High Rental Units Pending 29 58 29 36 15 21 Approved 18 57 39 43 43 Building Permit Issued 3 11 8 8 8 Certificate of Occuopancy 2 6 4 4 2 2 Under Appeal 4 11 7 9 9 Subtotal of AUD Medium High Rental Units 56 143 87 100 77 23 AUD Priority Housing Rental Units Pending 13 308 295 308 11 297 Approved 6 148 142 148 148 Building Permit Issued 0 89 89 89 89 Subtotal of AUD Priority Housing Rental Units 19 545 526 545 11 534 Grand Total: 87 971 884 926 117 809 The AUD Program has an initial duration of eight years or until 250 new units under the Program have been constructed in the High Density Residential or Priority Housing Overlay areas, whichever occurs first. Any application for new units that is deemed complete prior to the expiration of the Program may continue to be processed under the AUD Incentive Program. -

Strategies for Implementing Energy Targets and Design Pathways Preprint Rois Langner,1 Paul A

Transforming New Multifamily Construction to Zero: Strategies for Implementing Energy Targets and Design Pathways Preprint Rois Langner,1 Paul A. Torcellini,1 Matt Dahlhausen,1 David Goldwasser,1 Joe Robertson,1 and Sarah B. Zaleski2 1 National Renewable Energy Laboratory 2 U.S. Department of Energy Presented at the 2020 ACEEE Summer Study on Energy Efficiency in Buildings August 17–21, 2020 NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Conference Paper Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy NREL/CP-5500-77013 Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC September 2020 This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 Transforming New Multifamily Construction to Zero: Strategies for Implementing Energy Targets and Design Pathways Preprint Rois Langner,1 Paul A. Torcellini,1 Matt Dahlhausen,1 David Goldwasser,1 Joe Robertson,1 and Sarah B. Zaleski2 Suggested Citation Langner, Rois, Paul A. Torcellini, Matt Dahlhausen, David Goldwasser, Joe Robertson, and Sarah B. Zaleski. 2020. Transforming New Multifamily Construction to Zero: Strategies for Implementing Energy Targets and Design Pathways: Preprint. Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory. NREL/CP-5500-77013. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy20osti/77013.pdf. NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Conference Paper Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy NREL/CP-5500-77013 Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC September 2020 This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy National Renewable Energy Laboratory Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. -

Gurnell Grove, Ealing, W13 £130000

Acton 137 High Street London W3 6LY Tel: 020 8993 6767 [email protected] Gurnell Grove, Ealing, W13 £130,000 - Leasehold Studio, 1 Bathroom Preliminary Details *** CASH BUYERS ONLY ***A fantastic investment opportunity located on the borders of West Acton and Hanwell. The property itself would benefit from modernisation but being located on the ninth floor it benefits from amazing view to the south aspect. Internally the studio room features wood effect flooring and provides access to a separate kitchen area, the large bathroom has an excellent amount of space and comprises of a large corner bath, low level WC and pedestal wash basin. Gurnell Grove is a short walk from South Greenford and Castle Bar station as well as being moments from the A40. Key Features • Cash Buyers Only • Studio Apartment • Ninth Floor • Excellent Views • Lift • Separate Kitchen • In need of modernisation Acton | 137 High Street, London, W3 6LY | Tel: 020 8993 6767 | [email protected] 1 Area Overview Formerly a rural village forming part of the county of Middlesex, Ealing has grown into a thriving area, famous for the annual Jazz Festival held in Walpole Park that attracts lovers of Jazz from all over. Ealing is also home to Pitzhanger Manor which was reopened to the public in 1987 and is now a venue for contemporary art exhibitions where visitors can take guided tours around the house. © Collins Bartholomew Ltd., 2013 Nearest Stations Castle Bar Park (0.3M) South Greenford (0.5M) Drayton Green (0.7M) Acton | 137 High Street, London, W3 6LY | Tel: 020 8993 6767 -

LINDA R. STETYICK (Case No. 12204)

BEFORE THE BOARD OF ADJUSTMENT OF SUSSEX COUNTY IN RE: LINDA R. STETYICK (Case No. 12204) A hearing was held after due notice on September 17, 2018. The Board members present were: Mr. Dale Callaway, Ms. Ellen Magee, Mr. Bruce Mears, Mr. John Mills, and Mr. Brent Workman. Nature of the Proceedings This is an application for a special use exception for a garage / studio apartment. Findings of Fact The Board found that the Applicant is seeking a special use exception for a garage / studio apartment. This application pertains to certain real property located on the southeast side of Cordrey Road, approximately 432 feet south of Mount Joy Road (911 Address: 30580 Cordrey Road, Millsboro); said property being identified as Sussex County Tax Map Parcel Number 2-34-29.00-321.00. 1. The Board was given copies of the Application, an aerial photograph of the Property, and a portion of the tax map of the area. 2. The Board found that the Office of Planning & Zoning received no correspondence in support of or in opposition to the Application. 3. The Board found that Linda Stetyick was sworn in to testify about the Application. She submitted pictures of the Property and a letter of support from a neighbor for the Board to review. 4. The Board found that Ms. Stetyick testified that she purchased the Property in 1995 with her husband and that a permit was issued in 1996 to place a manufactured home on the property and join it to the existing cottage. The home has been used in this fashion since 1996. -

Micro Apartment Precedents Research Prof

$5&+ Micro Apartment Precedents Research Prof. Vidich Maksim Drapey Mayumi Tomita Cities have always attracted artists, writers, musicians, young professionals, and many other individuals seeking work and life experience; the time we live in is no exception. In fact, the number of singles looking for apartments to accommodate their lifestyle only continues to grow. As a result studio apartments have become scarce; unable to meet the demands of a growing SRSXODWLRQ,QDGGLWLRQWKHFRVWRIKRXVLQJLQFLWLHVOLNH1HZ<RUNVLJQLÀFDQWO\LQFUHDVHVZLWKHDFKSDVVLQJ\HDU1RZWKHGHPDQG for affordable living arrangements has reached a point of climax. 'HVLJQHUVDQG$UFKLWHFWVKDYHEHHQZRUNLQJZLWKWKHKHOSRIFLW\RIÀFLDOVWRFUHDWHDQHZW\SHVLQJOHOLYLQJVSDFHFDOOHG a “Micro Apartment.” The Micro can be described as a smaller version of a studio apartment. Designed as an affordable living unit for a single occupant, Micro Apartments are typically located in desirable locations, like that of Midtown Manhattan. %\VDFULÀFLQJÁRRUDUHDDQGFRQGHQVLQJDSDUWPHQWXQLWVWKHFRVWRIOLYLQJLQDVWXGLRDSDUWPHQWLQDFLW\HQYLURQPHQWFDQ EHVLJQLÀFDQWO\UHGXFHG*HQHUDOO\WKHSXEOLFFRQFHUQZLWK0LFUR$SDUWPHQWVLVWKDWWKHFRPSUHVVHGOLYLQJVSDFHZRXOGEH GDXQWLQJGLIÀFXOWDQGXQFRPIRUWDEOHWROLYHLQ+RZHYHULQVRPHFDVHVWUXHGHVLJQHUVDQGDUFKLWHFWVDUHQRZZRUNLQJGLOLJHQWO\ to create the ideal Micro Apartment. Many comfortable living spaces have been created from tiny footprints. Architects and designers have come up with clever, VXEWOHDQGDWWLPHVLQJHQLRXVVROXWLRQVWRWKHSUREOHPRIDOLYLQJVSDFHZLWKDOLPLWHGÁRRUDUHD1RWRQO\WKDWEXWRFFDVLRQDOO\ -

Making Room: Housing for a Changing America Is a Rallying Cry for a Wider Menu of Housing Options

Just as the housing needs of individuals change over a lifetime, unprecedented shifts in both demographics and lifestyle have fundamentally transformed our nation’s housing requirements. • Adults living alone now account for nearly 30 percent of American households. • While only 20 percent of today’s households are nuclear families, the housing market largely remains fixated on their needs. • By 2030, 1 in 5 people in the United States will be age 65 or over — and by 2035, older adults are projected to outnumber children for the first time ever. • The nation’s housing stock doesn’t fit the realities of a changing America. Featuring infographics, ideas, solutions, photographs and floor plans from the National Building Museum exhibition of the same name, Making Room: Housing for a Changing America is a rallying cry for a wider menu of housing options. Visit AARP.org/MakingRoom to download a PDF of this publication or order a free printed edition. The National Building Museum inspires curiosity about the world we design and build through AARP is the nation’s largest nonprofit, nonpartisan exhibitions and programming that organization dedicated to empowering people 50 explore how the built world shapes and older to choose how they live as they age. The our lives. Located in Washington, D.C., the Museum AARP Livable Communities initiative works nationwide believes that understanding the history and impact AARP to support the efforts of neighborhoods, towns, cities of architecture, engineering, landscape architecture, and rural areas to be livable for people of all ages. construction, and design is important for all ages. -

Mid-Century Studio Apartment Inventory Form

Historic Property Inventory Report Location Field Site No. DAHP No. Historic Name: Studio Apartment Common Name: Property Address: 1102 6th Ave W, Spokane, WA 99204 Comments: Tax No./Parcel No. 35192.4306 Plat/Block/Lot Acreage .3 Supplemental Map(s) Township/Range/EW Section 1/4 Sec 1/4 1/4 Sec County Quadrangle T25R43E 19 Spokane SPOKANE NW Coordinate Reference Easting: 2397394 Northing: 859823 Projection: Washington State Plane South Datum: HARN (feet) Thursday, May 28, 2015 Page 1 of 10 Historic Property Inventory Report Identification Survey Name: Spokane Mid-Century Studio Apartment Date Recorded: 02/10/2015 Field Recorder: Emily Vance Owner's Name: Sixco, LLC Owner Address: 10223 S Hangman Valley Road City: Spokane State: Washington Zip: 99224 Classification:Building Resource Status: Comments: Survey/Inventory Within a District? No Contributing? National Register: Local District: National Register District/Thematic Nomination Name: Eligibility Status: Not Determined - SHPO Determination Date: 1/1/0001 Determination Comments: Description Historic Use: Domestic - Multiple Family House Current Use: Commerce/Trade - Organizational Plan: Rectangle Stories: 3 Structural System: Concrete - Reinforced Concrete Changes to Plan: Intact Changes to Interior: Intact Changes to Original Cladding: Moderate Changes to Windows: Intact Changes to Other: Other (specify): Style: Cladding: Roof Type: Roof Material: Modern - Miesian Concrete - Poured Flat with Parapet Asphalt / Composition - Modern - International Veneer - Vinyl Siding Built Up Style -

HOUSING TYPE EXAMPLES Los Gatos General Plan 2040 GPAC

HOUSING TYPE EXAMPLES Los Gatos General Plan 2040 GPAC EXHIBIT 5 Town of Los Gatos | General Plan Advisory Committee Accessory Dwelling Units Accessory dwelling units (ADUs) are an additional dwelling unit to a primary residence. They are known by many names: granny flats, in-law units, backyard cottages, secondary units, and more. ADUs are an innovative, affordable, effective option for adding much- needed housing. ADUs can be detached and newly constructed units, converted garages or basements, or built above a garage or workshop. New Laws to Streamline ADU Construction Over the past few years, the California legislature has made efforts to streamline ADU construction. This includes: • Making ADU approval a ministerial action, • Mandating that local governments approve ADU building permit requests if the ADU meets certain standards, • Allowing ADUs to be built in all zoning districts that allow single-family uses, • Reducing or eliminating ADU parking requirements, and • Reducing ADU utility-related fee requirements. 2 Housing Type Examples | August 2019 Tiny Homes The tiny-house movement is an architectural and social movement that promotes living simply, financial prudence, and safe, shared community experiences. Tiny homes are generally defined as residential structures under 400 sq. ft. They can built on permanent foundations or trailers. Duplexes A duplex has two dwelling units attached to one another with separate entrances for each. This includes two-story houses with a complete apartment on each floor and side-by-side apartments on a single lot that share a common wall. 3 Town of Los Gatos | General Plan Advisory Committee Triplexes and Fourplexes A triplex has three dwelling units attached to one another with separate entrances for each, while a fourplex has four dwelling units. -

Well Presented Studio Apartment in One Of

WELL PRES ENTED STUDIO APARTMENT IN ONE OF ISLINGTON'S PREMIER TERRACES. 14A, HIGHBURY PLACE, HIGHBURY, ISLINGTON, LONDON, N5 1QP Furnished, £275 pw (£1,191.67 pcm) + £285 inc VAT tenancy paperwork fee and other charges apply.* Available from 05/05/2019 WELL PRESENTED STUDIO APART MENT IN ONE OF ISLINGTON'S PREMIER TERRAC ES. 14A HIGH BURY PLACE, HIGHBURY, ISLINGTON, LONDON, N5 1QP £275 pw (£1,191.67 pcm) Furnished • 1 Bathrooms • Beautiful location • Studio apartment • Communal gardens • Neutrally decorated • Overlooking Highbury Fields • EPC Rating = C • Council Tax = C S ituation Highbury is a residential suburb in the London Borough of Islington. The area has traditionally had a very friendly, mixed demographic, from music producers to bankers, comedians and journalists to lawyers and politicians. Within a short walk of Highbury & Islington Station is the open space of Highbury Fields surrounded by impressive Georgian and Victorian architecture, popular in the summer months with outdoor public tennis and netball courts and a small indoor fitness centre and pool. Highbury Barn is a small parade of independent award winning local shops and amenities, including Godfrey's butchers and Highbury Vintners. Housing stock in the area is largely Victorian and Georgian, ranging from the grand villas of Highbury Hill and the huge flat fronted town houses of Highbury Place to the pretty, tree lines streets east of Petherton Road and north of Highbury Fields. Description Set on the ground floor of an impressive terrace house on Highbury Place this studio apartment is well presented and has direct access to the communal garden. Neutrally decorated with a sofa and separate bed, the kitchen is open plan and there is a separate shower room.