Using Charter Damages to Provide Meaningful Redress and Promote State Accountability: a Re-Examination of the Omar Khadr Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada's G8 Plans

Plans for the 2010 G8 Muskoka Summit: June 25-26, 2010 Jenilee Guebert Director of Research, G8 Research Group, with Robin Lennox and other members of the G8 Research Group June 7, 2010 Plans for the 2010 G8 Muskoka Summit: June 25-26, Ministerial Meetings 31 2010 1 G7 Finance Ministers 31 Abbreviations and Acronyms 2 G20 Finance Ministers 37 Preface 2 G8 Foreign Ministers 37 Introduction: Canada’s 2010 G8 2 G8 Development Ministers 41 Agenda: The Policy Summit 3 Civil Society 43 Priority Themes 3 Celebrity Diplomacy 43 World Economy 5 Activities 44 Climate Change 6 Nongovernmental Organizations 46 Biodiversity 6 Canada’s G8 Team 48 Energy 7 Participating Leaders 48 Iran 8 G8 Leaders 48 North Korea 9 Canada 48 Nonproliferation 10 France 48 Fragile and Vulnerable States 11 United States 49 Africa 12 United Kingdom 49 Economy 13 Russia 49 Development 13 Germany 49 Peace Support 14 Japan 50 Health 15 Italy 50 Crime 20 Appendices 50 Terrorism 20 Appendix A: Commitments Due in 2010 50 Outreach and Expansion 21 Appendix B: Facts About Deerhurst 56 Accountability Mechanism 22 Preparations 22 Process: The Physical Summit 23 Site: Location Reaction 26 Security 28 Economic Benefits and Costs 29 Benefits 29 Costs 31 Abbreviations and Acronyms AU African Union CCS carbon capture and storage CEIF Clean Energy Investment Framework CSLF Carbon Sequestration Leadership Forum DAC Development Assistance Committee (of the Organisation for Economic Co- operation and Development) FATF Financial Action Task Force HAP Heiligendamm L’Aquila Process HIPC heavily -

Government Turns the Other Way As Judges Make Findings About Torture and Other Abuse

USA SEE NO EVIL GOVERNMENT TURNS THE OTHER WAY AS JUDGES MAKE FINDINGS ABOUT TORTURE AND OTHER ABUSE Amnesty International Publications First published in February 2011 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2011 Index: AMR 51/005/2011 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.2 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 Judges point to human rights violations, executive turns away ........................................... 4 Absence -

Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan

Fall 08 September 2012 Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians From US Drone Practices in Pakistan International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic Stanford Law School Global Justice Clinic http://livingunderdrones.org/ NYU School of Law Cover Photo: Roof of the home of Faheem Qureshi, a then 14-year old victim of a January 23, 2009 drone strike (the first during President Obama’s administration), in Zeraki, North Waziristan, Pakistan. Photo supplied by Faheem Qureshi to our research team. Suggested Citation: INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION CLINIC (STANFORD LAW SCHOOL) AND GLOBAL JUSTICE CLINIC (NYU SCHOOL OF LAW), LIVING UNDER DRONES: DEATH, INJURY, AND TRAUMA TO CIVILIANS FROM US DRONE PRACTICES IN PAKISTAN (September, 2012) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I ABOUT THE AUTHORS III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS V INTRODUCTION 1 METHODOLOGY 2 CHALLENGES 4 CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 7 DRONES: AN OVERVIEW 8 DRONES AND TARGETED KILLING AS A RESPONSE TO 9/11 10 PRESIDENT OBAMA’S ESCALATION OF THE DRONE PROGRAM 12 “PERSONALITY STRIKES” AND SO-CALLED “SIGNATURE STRIKES” 12 WHO MAKES THE CALL? 13 PAKISTAN’S DIVIDED ROLE 15 CONFLICT, ARMED NON-STATE GROUPS, AND MILITARY FORCES IN NORTHWEST PAKISTAN 17 UNDERSTANDING THE TARGET: FATA IN CONTEXT 20 PASHTUN CULTURE AND SOCIAL NORMS 22 GOVERNANCE 23 ECONOMY AND HOUSEHOLDS 25 ACCESSING FATA 26 CHAPTER 2: NUMBERS 29 TERMINOLOGY 30 UNDERREPORTING OF CIVILIAN CASUALTIES BY US GOVERNMENT SOURCES 32 CONFLICTING MEDIA REPORTS 35 OTHER CONSIDERATIONS -

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord .......................................................................... -

Interrogation, Detention, and Torture DEBORAH N

Finding Effective Constraints on Executive Power: Interrogation, Detention, and Torture DEBORAH N. PEARLSTEIN* INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................1255 I. EXECUTIVE POLICY AND PRACTICE: COERCIVE INTERROGATION AND T O RTU RE ....................................................................................................1257 A. Vague or Unlawful Guidance................................................................ 1259 B. Inaction .................................................................................................1268 C. Resources, Training, and a Plan........................................................... 1271 II. ExECuTrVE LIMITs: FINDING CONSTRAINTS THAT WORK ...........................1273 A. The ProfessionalM ilitary...................................................................... 1274 B. The Public Oversight Organizationsof Civil Society ............................1279 C. Activist Federal Courts .........................................................................1288 CONCLUSION ........................................................................................................1295 INTRODUCTION While the courts continue to debate the limits of inherent executive power under the Federal Constitution, the past several years have taught us important lessons about how and to what extent constitutional and sub-constitutional constraints may effectively check the broadest assertions of executive power. Following the publication -

REAL PROPERTY REPORTS Fifth Series/Cinqui`Eme S´Erie Recueil De Jurisprudence En Droit Immobilier VOLUME 52 (Cited 52 R.P.R

REAL PROPERTY REPORTS Fifth Series/Cinqui`eme s´erie Recueil de jurisprudence en droit immobilier VOLUME 52 (Cited 52 R.P.R. (5th)) EDITORS-IN-CHIEF/REDACTEURS´ EN CHEF Jeffrey W. Lem, B.COMM., LL.B., LL.M. John Mascarin, M.A., LL.B. Director of Titles for the Province of Ontario Aird & Berlis LLP Toronto, Ontario Toronto, Ontario QUEBEC EDITOR/REDACTEUR´ POUR LE QUEBEC´ Fredric Carsley, B.A., B.C.L., LL.B. De Grandpr´e Chait LLP/s.e.n.c.r.l. Montr´eal, Qu´ebec ASSOCIATE EDITORS/REDACTEURS´ ADJOINTS Reuben M. Rosenblatt, Q.C., LSM Bruce Ziff, B.A., LL.B., M.LITT. Minden Gross LLP Faculty of Law, University of Alberta Toronto, Ontario Edmonton, Alberta Paul De Francesca, B.A.A., LL.B. Craig R. Carter, B.SC., LL.B., LL.M. De Francesca Law Office Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP Toronto, Ontario Toronto, Ontario CARSWELL EDITORIAL STAFF/REDACTION´ DE CARSWELL Cheryl L. McPherson, B.A.(HONS.) Director, Primary Content Operations Sarah Bourne, B.A., LL.B. Product Development Manager Julia Fischer, B.A.(HONS.), LL.B. Nicole Ross, B.A., LL.B. Supervisor, Legal Writing Supervisor, Legal Writing Andrea Andrulis, B.A., LL.B., LL.M. Eden Nameri, B.A., LL.B. Senior Legal Writer Senior Legal Writer Martin-Fran¸cois Parent, LL.B., LL.M., Jackie Bowman DEA (PARIS II) Senior Content Editor Bilingual Legal Writer REAL PROPERTY REPORTS, a national series of annotated topical law re- Recueil de jurisprudence en droit immobilier, une s´erie nationale de ports, is published 12 times per year. -

2009 FC 405 Vancouver, British Columbia, April 23, 2009 PRESENT

Date: 20090423 Docket: T-1228-08 Citation: 2009 FC 405 Vancouver, British Columbia, April 23, 2009 PRESENT: The Honourable Mr. Justice O'Reilly BETWEEN: OMAR AHMED KHADR Applicant and THE PRIME MINISTER OF CANADA, THE MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS, THE DIRECTOR OF THE CANADIAN SECURITY INTELLIGENCE SERVICE, AND THE COMMISSIONER OF THE ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE Respondents REASONS FOR JUDGMENT AND JUDGMENT [1] Mr. Omar Khadr, a Canadian citizen, was arrested in Afghanistan in July 2002 when he was 15 years old. He is alleged to have thrown a grenade that caused the death of a U.S. soldier. He has been imprisoned at Guantánamo Bay since October 2002 awaiting trial on serious charges: murder, conspiracy and support of terrorism. Page: 2 [2] Mr. Khadr challenges the refusal of the Canadian Government to seek his repatriation to Canada. He claims that his rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (sections 6, 7 and 12) have been infringed and seeks a remedy under s. 24(1) of the Charter. More particularly, Mr. Khadr asks me to quash the decision of the respondents not to seek his return to Canada and order the respondents to request the United States Government to repatriate him. Mr. Khadr also asks me to overturn the respondents’ decision on the grounds that it was unreasonable and taken in bad faith. Finally, Mr. Khadr seeks further disclosure of documents in the respondents’ possession. [3] I am satisfied, in the special circumstances of this case, that Mr. Khadr’s rights under s. 7 of the Charter have been infringed. -

Transportation

TRANSPORTATION POLICY BRIEFING THE HILL TIMES, APRIL 6, 2015 TRANSPORT MINISTER LISA RAITT NDP MP HOANG MAI Pilot behaviour seen in Germanwings crash Railway safety: a disconcerting lack of ‘would not happen in Canada’: Raitt regulatory oversight CONSERVATIVE MP LARRY MILLER LAC-MÉGANTIC Miller says House Transport Committee’s Getting the big picture right: regulating rail report will help strengthen transportation transportation of crude oil after safety in Canada Lac-Mégantic disaster LIBERAL MP DAVID MCGUINTY AIR TAXIS Canadians continue to be deeply concerned Government needs to support smaller about rail safety, and rightly so. airports as TSB investigates air taxis LASER STRIKES RAIL SAFETY Transport Canada data indicates rates of laser Opposition supporting rail safety bill to boost strikes continue to rise ministerial oversight, shipper liability ASIA TRADE Grain competing with other products in western rail as Asian trade prioritized 20 THE HILL TIMES, MONDAY, APRIL 6, 2015 TRANSPORTATION POLICY BRIEFING Q&A LISA RAITT Pilot behavior seen in Germanwings crash ‘would not happen in Canada’: Raitt BY RACHEL AIELLO to market. So if we’re signing all timistic that it’ll go through and I these free trade agreements, we am grateful for the support of the ransport Minister Lisa Raitt need to make sure the entire sup- opposition.” Tsays she’s confi dent the ply chain is ready to go and fi ring current annual medical checks and that’s what he’s doing. The new Railway Safety Manage- for Canadian pilots are enough “So for me, day-to-day, it’s ment System (SMS) regulations to ensure the safety of all aboard about safety, but the bigger picture came into effect April 1. -

The War in Yemen: 2011-2018: the Elusive Road to Peace

Working Paper 18-1 By Sonal Marwah and Tom Clark The War in Yemen: 2011-2018 The elusive road to peace November 2018 The War in Yemen: 2011-2018 The elusive road to peace By Sonal Marwah and Tom Clark Working Paper 18-1 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publications Data The War in Yemen: 2011-2018: The elusive road to peace ISBN 978-1-927802-24-3 © 2018 Project Ploughshares First published November 2018 Please direct enquires to: Project Ploughshares 140 Westmount Road North Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G6 Canada Telephone: 519-888-6541 Email: [email protected] Editing: Wendy Stocker Design and layout: Tasneem Jamal Table of Contents Glossary of Terms i List of Figures ii Acronyms and Abbreviations iii Acknowledgements v Executive Summary 1 Introduction 2 Background 4 Participants in the Conflict 6 Major local actors 6 Foreign and regional actors 7 Major arms suppliers 7 Summary of the Conflict (2011-2018) 8 Civil strife breaks out (January 2011 to March 2015) 8 The internationalization of conflict (2015) 10 An influx of weapons and more human-rights abuses (2016) 10 A humanitarian catastrophe (2017- June 2018) 13 The Scale of the Forgotten War 16 Battle-related deaths 17 Forcibly displaced persons 17 Conflict and food insecurity 22 Infrastructural collapse 23 Arming Saudi Arabia 24 Prospects for Peace 26 Regulation of Arms Exports 30 The Path Ahead and the UN 32 Conclusion 33 Authors 34 Endnotes 35 Photo Credits 41 Glossary of Terms Arms Trade Treaty: A multilateral treaty, which entered into force in December 2014, that establishes -

No Torture. No Exceptions

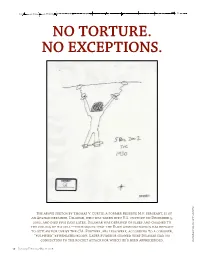

NO TORTURE. NO EXCEPTIONS. The above sketch by Thomas V. Curtis, a former Reserve M.P. sergeant, is of New York Times an Afghan detainee, Dilawar, who was taken into U.S. custody on December 5, 2002, and died five days later. Dilawar was deprived of sleep and chained to the ceiling of his cell—techniques that the Bush administration has refused to outlaw for use by the CIA. Further, his legs were, according to a coroner, “pulpified” by repeated blows. Later evidence showed that Dilawar had no connection to the rocket attack for which he’d been apprehended. A sketch by Thomas Curtis, V. a Reserve M.P./The 16 January/February/March 2008 Introduction n most issues of the Washington Monthly, we favor ar- long-term psychological effects also haunt patients—panic ticles that we hope will launch a debate. In this issue attacks, depression, and symptoms of post-traumatic-stress Iwe seek to end one. The unifying message of the ar- disorder. It has long been prosecuted as a crime of war. In our ticles that follow is, simply, Stop. In the wake of Septem- view, it still should be. ber 11, the United States became a nation that practiced Ideally, the election in November would put an end to torture. Astonishingly—despite the repudiation of tor- this debate, but we fear it won’t. John McCain, who for so ture by experts and the revelations of Guantanamo and long was one of the leading Republican opponents of the Abu Ghraib—we remain one. As we go to press, President White House’s policy on torture, voted in February against George W. -

2018-2019 President Jeffrey S. Leon, Lsm and His Wife

2018-2019 PRESIDENT JEFFREY S. LEON, LSM AND HIS WIFE, CAROL BEST, CALL TWO PLACES HOME – TORONTO, ONTARIO AND SCOTTSDALE, ARIZONA. ISSUE 88 | FALL | 2018 ISSUE 88 | FALL American College of Trial Lawyers JOURNAL CONTENTS Chancellor-Founder Hon. Emil Gumpert FEATURES (1895-1982) 23711 OFFICERS Letter from the Editor President’s Perspective Profile: 2018-2019 President Missouri Fellow Samuel H. Franklin President Jeffrey S. Leon, LSM Rights The Wrongs Jeffrey S. Leon, LSM President-Elect Douglas R. Young Treasurer Rodney Acker Secretary 15 17 21 27 Bartholomew J. Dalton Immediate Past President Book Review: A The Thalidomide Saga Justice Jackson & the Fellows Share War BOARD OF REGENTS “Practical Treatise” in Canada Nuremberg Trials Stories RODNEY ACKER THOMAS M. HAYES, III Dallas, Texas Monroe, Louisiana 29 45 RITCHIE E. BERGER PAUL J. HICKEY Fellows’ Other Lives Tribute to Past Burlington, Vermont Cheyenne, Wyoming President Jimmy Morris SUSAN S. BREWER JEFFREY S. LEON, LSM Morgantown, West Virginia Toronto, Ontario BARTHOLOMEW J. DALTON MARTIN F. MURPHY Wilmington, Delaware Boston, Massachusetts JOHN A. DAY WILLIAM J. MURPHY COLLEGE MEETINGS Brentwood, Tennessee Baltimore, Maryland RICHARD H. DEANE, JR. DANIEL E. REIDY 31 35 37 40 Atlanta, Georgia Chicago, Illinois Region 6 Meeting Region 13 Meeting Region 12 Meeting Texas Fellows MONA T. DUCKETT, Q.C. STEPHEN G. SCHWARZ Recap Recap Recap Annual Luncheon Edmonton, Alberta Rochester, New York KATHLEEN FLYNN PETERSON ROBERT K. WARFORD Minneapolis, Minnesota San Bernardino, California SAMUEL H. FRANKLIN ROBERT E. WELSH, JR. Birmingham, Alabama Philadelphia, Pennsylvania SUSAN J. HARRIMAN DOUGLAS R. YOUNG San Francisco, California San Francisco, California FELLOWS IN ACTION EDITORIAL BOARD Stephen M. -

The Al Qaeda Network a New Framework for Defining the Enemy

THE AL QAEDA NETWORK A NEW FRAMEWORK FOR DEFINING THE ENEMY KATHERINE ZIMMERMAN SEPTEMBER 2013 THE AL QAEDA NETWORK A NEW FRAMEWORK FOR DEFINING THE ENEMY KATHERINE ZIMMERMAN SEPTEMBER 2013 A REPORT BY AEI’S CRITICAL THREATS PROJECT ABOUT US About the Author Katherine Zimmerman is a senior analyst and the al Qaeda and Associated Movements Team Lead for the Ameri- can Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project. Her work has focused on al Qaeda’s affiliates in the Gulf of Aden region and associated movements in western and northern Africa. She specializes in the Yemen-based group, al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and al Qaeda’s affiliate in Somalia, al Shabaab. Zimmerman has testified in front of Congress and briefed Members and congressional staff, as well as members of the defense community. She has written analyses of U.S. national security interests related to the threat from the al Qaeda network for the Weekly Standard, National Review Online, and the Huffington Post, among others. Acknowledgments The ideas presented in this paper have been developed and refined over the course of many conversations with the research teams at the Institute for the Study of War and the American Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project. The valuable insights and understandings of regional groups provided by these teams directly contributed to the final product, and I am very grateful to them for sharing their expertise with me. I would also like to express my deep gratitude to Dr. Kimberly Kagan and Jessica Lewis for dedicating their time to helping refine my intellectual under- standing of networks and to Danielle Pletka, whose full support and effort helped shape the final product.