India Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abhyaas Newsboard... for the Quintessential Test Prep Student

November 5, 2019 Abhyaas Newsboard... For the quintessential test prep student Persons in News 1. On October 11, 2019, Forbes India Rich List 2019 was released by Forbes India in which Mukesh Ambani, aged 62, Chairman of Reliance Industries Ltd (RIL) held the top spot for the 12th consecutive year with a net worth of $51.4 billion. 2. Chairman and Managing Director of JSW Steel, Sajjan Jindal has been appointed as the Vice-Chairman of World Steel Association (Worldsteel). He is appointed for a period of one year. The association also elected YU Yong, Chairman, HBIS Group Co, as Chairman. Apart from this, the board also elected a 14-member Executive Committee. 3. As per the Appointments Committee of the Cabinet (ACC), Government of India(GoI), Pankaj Kumar (a 1987 batch Indian Administrative Service -IAS officer of Nagaland cadre) has been appointed as the new CEO (Chief Executive Officer) of the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI). He replaces Ajay Bhushan Pandey. 4. President Ram Nath Kovind has formally approved the appointment of Justice SA Bobde as the next Chief Justice of India. Justice Bobde will be sworn in as the 47th CJI a day after the retirement of current CJI Ranjan Gogoi. CJI Gogoi had himself recommended Justice Bobde’s name for the post. 5. The Central Government has appointed Girish Chandra Murmu as the first Lieutenant Governor of J&K UT and Radha Krishna Mathur as the first LG of Ladakh. The current J&K Governor Satya Pal Malik has been appointed as the new Governor of Goa. -

16 Subordinate Legislation 38.Pdf

""~38 "~-- COMMITTEE ON SUBORDINATE LEGISLATION (2018-2019) (SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA) THIRTY-EIGTH REPORT RULES/REGULATIONS GOVERNING THE SERVICE CONDITIONS OF DELHI, ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS CIVIL SERVICE AND CENTRAL SECRETARIAT SERVICE LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI JANUARY, 2019/PAUSHA, 1940 (Saka) I) .Q.QJl/!.!\/!ffTEE ON SUBORDJNATE LEG IS LA llON (2018-2019) (SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA) DRAFT THIRTY•EIGTH REPORT RULES/REGULATIONS GOVERNING THE SERVICE CONDITIONS OF DELHI, ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS CIVIL SERVICE AND CENTRAL SECRETARIAT SERVICE ~ 0 3 JAN? (PRESENTED TO LOK SABHA ON ~-· Janua:r9,li19) LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI JANUARY, 2019/PAUSHA, 1940 (Saka) Para No. Page No. COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITIEE ......................................... (iii) INTRODUCTION ....................................................................... (v) REPORT PART-I I. Introduction-Delhi, Andaman & Nicobar Islands Civil Service (DANICS) II. Central Secretariat Service (CSS) PART-II I. Observations/Recommendations 25-3.l. ANNEXURE Secretary, Ministry of Personnel, PG and Pensions, 0.0. No. 21/2/2015-CS-I (D) dated 31st July, 2015 33 P,PPENDICES 1. 2. Minutes of the Third Sitting (2016-17) c;if the Committee held on 23.11.2015. Extracts from the Minutes of the Third Sitting of the Committee (2018-2019) held on 20.12.2018. COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE ON SUBORDINATE LEGISLATION (16th LOK SABHA) (2018·2019) Shri Dilipkumar Mansukhlal Gandhi Chairperson Member~ 2. Shri Idris Ali 3. Shri Birendra Kumar Choudhary 4. Shri S. P. Muddahanumegowda 5. Shri Shyama Charan Gupta 6. Shri Jhina Hikaka 7. Shri Janardan Mishra 8. Shri Prem Das Rai 9. Shri Chandul Lal Sahu 10'. Shri Alok Sanjar 11. Shri Ram Prasad Sarmah 12. Adv. Narendra Keshav Sawaikar 13. -

Download Caruna Report

The Civil Services have risen to the summon of the Nation, echoed by the clarion call of the Hon’ble Prime Minister to build a silo-less culture of service. The creation of the unique collective-CARUNA, the Civil Services Associations Reach to Support in Natural Disasters is the embodiment of this new work culture, where transcending narrow service loyalties and surmounting a culture of seniority, this platform has evolved to be the first Flat Organization in recent civil service memory. The CARUNA Team representing 29 services of the Union of India is a befitting response to Sardar Patel’s advice when he said “you must cultivate an ‘esprit de corps’ without which a Service as such has little meaning”. The founder of modern civil services in India, Sardar Patel, invoked the spirit of sacrifice amongst civil servants by exhorting them … ‘not only will you be the administrators of areas allotted to you, but you will also be the servants of people’. The numerous activities of our CARUNA warriors, their help to citizens on ground, their assistance to colleagues battling the COVID-19 pandemic and their creative administrative solutions are a humble tribute at his great feet. The transformation of Civil Services into a virtuous weapon of high-minded devotion at this perilous hour, is a resolute rededication on the CIVIL SERVICES DAY, 21st April, 2020. We, the members of the Civil Services of India humbly place this document of service done during the past 21 days combatting the COVID-19 situation, at the altar of our true masters- the Citizens of India. -

Human Rights in India Unit-4

UNIT-4 Human Rights in India – Constitutional Provisions / Guarantees HUMAN RIGHTS IN INDIA REPUBLIC OF INDIA This article is part of a series on the politics and government of India 1. Union Government • Constitution of India • Fundamental rights Executive: • President • Vice President • Prime Minister • Union Council of Ministers • Cabinet Secretary of India • Civil Services of India Parliament: • RajyaSabha • LokSabha • The Chairman • The Speaker Judiciary: • Supreme Court of India • Chief Justice of India • High Courts • District Courts 2. Elections • Election Commission • Chief Election Commissioner 3. Political parties • National parties • State parties 4. National coalitions: • National Democratic Alliance (NDA) • United Progressive Alliance (UPA) 5. State Govt. and Local Govt. • Governor • Chief minister State level • Vidhan Sabha • Vidhan Parishad Local Governments: • Divisional commissioner • District Magistrate • Zilla Panchayats • Mandal or Taluk Panchayats • Gram Panchayats • Urban bodies • Municipal Corporations • Municipal Councils • Nagar Panchayats DEFNITION : Human rights in India is an issue complicated by the country's large size & population, widespread poverty, lack of proper education & its diverse culture, even though being the world's largest sovereign, secular, democratic republic. The Constitution of India provides for Fundamental rights, which include freedom of religion. Clauses also provide for freedom of speech, as well as separation of executive and judiciary and freedom of movement within the country and abroad. The country also has an independent judiciary and well as bodies to look into issues of human rights. The 2016 report of Human Rights Watch accepts the above-mentioned faculties but goes to state that India has "serious human rights concerns. Civil society groups face harassment and government critics face intimidation and lawsuits. -

"Failure Will Never Overtake Me If My Determination to Succeed Is

04 ,2019 Important Days in October 1 October - International Coffee Day 2 October - Gandhi Jayanti 3 October - German Unity Day 4 October - World Animal Welfare Day 5 October - World Teachers' Day 6 October - German-American Day 8 October - Indian Air Force Day 9 October - World Postal Day 10 October - World Mental Health Day 11 October - International Girl Child Day 1. Mongolian joint military training exercise Nomadic Elephant-XIV to be held at Bakloh Himachal Pradesh. Mongolian joint military training, Exercise Nomadic Elephant-XIV, being conducted over a period of 14 days, will commence from 05 Oct 2019. The exercise will be conducted from 05 Oct 19 to 18 Oct 19 at Bakloh. The Mongolian Army is being represented by officers and troops of the elite 084 Air Borne Special Task Battalion while Indian Army is being represented by a contingent of a battalion of RAJPUTANA RIFLES. Nomadic Elephant-XIV aims to train troops in counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism operations under the United Nations mandate. It aims to enhance defence co-operation and military relations between the two countries. The exercise will provide a platform to share the experiences and best practices of the two countries and gain mutually during the joint training. Foot Notes: About Himachal Pradesh 1. Governor: Bandaru Dattatreya 2. Capital: Shimla 3. Chief Minister: Jai Ram Thakur 2. Ben Stokes Wins PCA Players' Player of Year Award Ben Stokes voted Players Player of the Year at the Professional Cricketers Association awards. Stokes played a starring role in England's first 50-over World Cup triumph culminating in his dynamic man-of-the-match display in their dramatic final win against New Zealand in July. -

Surendra Nath Commitee Report -2003

Department o f Personnel & Training Shri AX. Agarwal Former Secretory, Dept. o f Personnel & I Truinina Lt. Cen (Retd.) Surinder Nath Former Chairman, Additional Secretary, Dr. Prodipto Ghosh Department o f Economic Affairs THE SYSTEM OF PERFORMANCE APPRMSAL, PROMOTION, EMPANELIEWT AND PlACEMiENT REPORT OF THE GROUP CONSTITUTED TO REVIEW Contents Acknowledgements .I.................................. 6 Executive Summary ................................... 7 I . Introduction & Methodology ...................... 25 Part I . Performance Appraisal ...................... 29 2 . The Present System .............................. 30 3 . Strengths and Weaknesses of the Current System of Performance Appraisal .. ..........33 4 . Objectives of Performance Appraisal ............. 36 5 . Other recommendations relating to performance appraisal ............................... 56 6 . Redesigning the PAR Format and Personal Dossier . 71 Part I1 - Promotions, Empanelment & Placements ...... 77 7 . The current system............................... 78 8 . Weaknesses of the current system ................ 82 9 . Recommendations relating to Promotions .......... 85 10 . Recommendations relating to Empanelment and Placements in the Government of India ........... 95 Part Ill . Annexures ...................................... 103 List of those whom the Group met .................... 110 Gist of suggestions received ........................ 112 List of Organizations/Agencies whose performance appraisal systems were studied............................................. -

Seminar on Sharing of Good Practices on Migration Governance 1

Seminar on Sharing of Good Practices on Migration Governance 1 Seminar on Sharing of Good Practices on Migration Governance Minutes of the seminar 10 July 2019 New Delhi, India This seminar was funded by the European Union (EU) through EU-India Cooperation and Dialogue on Migration and Mobility project (CDMM) and the Government of India (GoI). The project is implemented by International Labour Organization (ILO) and International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), with India Centre for Migration as local partner. This consultation report was produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the International Labour Organization (ILO) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union and Government of India. The responsibility for opinions expressed rests solely with the presenters, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the ILO of the opinions expressed in them. Licensed to the European Union under conditions. Executive Summary .................................................................................................5 I: Inaugural Session ...........................................................................................6 II: Launch of the Integration Handbook for Indian Diaspora in Italy and Students Checklist .......................................10 III: Setting The Context ......................................................................................12 IV. Regular Migration & Well-Managed Mobility ............................................16 -

Envoy Excellency Magazine in Association with Embassy of India, Berne, Switzerland

Contents Message from Ambassador of India to Switzerland, The Holy See and Liechtenstein ............................................................4 Message from Ambassador of Switzerland to India ..............................................................................................................6 Interview with Minister of State for Tourism (IC) and Minister for Electronics and Information Technology, Govt. of India .... 10 Interview with Ambassador of India to Switzerland ............................................................................................................14 Country Profile – Switzerland & India ................................................................................................................................17 India- Switzerland Friendship Treaty, 1948 .........................................................................................................................22 India-Switzerland 70 year of Friendship (1948-2018) .........................................................................................................25 India-Switzerland High Level Visits ....................................................................................................................................30 India - Switzerland Cultural Exchange ................................................................................................................................32 Indian Diaspora in Switzerland ...........................................................................................................................................35 -

The Indian Civil Service and Indian Foreign Policy, 1923–1961

THE INDIAN CIVIL SERVICE AND INDIAN FOREIGN POLICY, 1923–1961 Amit Das Gupta First published 2021 ISBN: 978-1-138-06424-9 (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-003-11884-8 (ebk) 1 INTRODUCTION (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) 1 INTRODUCTION Jawaharlal Nehru left a strong imprint on global affairs. Charismatic, handsome and a brilliant orator and writer, he led the largest decolonised country, setting examples with state-driven industrialisation and efforts to establish a new style in foreign affairs. He gave those a face and a voice who, until the end of the Second World War, had been denied looking after their own affairs and having a say in international politics. As Nehru was a towering figure at home and abroad, the years between 1947 and 1964 are rightfully termed the Nehruvian era. Accordingly, books on Indian foreign policy mostly start with the assumption that Nehru was its main or even sole architect. It appears to be self-evident that a country’s first prime min- ister would set everything on the right track, all the more so as Nehru was considered a foreign affairs expert even before India attained independence. Nevertheless, foreign policy never is a one-man show. Apart from Nehru’s main advisor, V. K. Krishna Menon, ministers like Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel or G. B. Pant exercised a certain influence. At least equally important was the support and the counsel of officers of India’s Foreign Service (IFS), who ena- bled Nehru to pursue his goals in the international arena. The vast majority of them were neither mere tools to implement decisions nor men or women of Nehru’s making. -

Seminar on Sharing of Good Practices on Migration Governance Silver Oak Hall, India Habitat Centre, Lodi Road New Delhi, India 10 July 2019 Agenda

India –EU Common Agenda on Migration and Mobility India-EU Cooperation and Dialogue on Migration and Mobility Project Seminar on Sharing of Good Practices on Migration Governance Silver Oak Hall, India Habitat Centre, Lodi Road New Delhi, India 10 July 2019 Agenda 10:00 -10:30 Registration/Coffee 10:30: 11:20 Opening Remarks: Sh. Vinod K Jacob, Joint Secretary, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India Mr. Tomasz Kozlowski, Ambassador of the European Union to India and Inaugural Address: Ms. Paraskevi Michou, Director General, DG- Home Affairs, European Commission and Sh. Sanjiv Arora, Secretary CPV & OIA Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India Launch of Handbook for Integration of Indians in Italy and Student Checklist 11:20 -11:45 Tea 11:45 -12:15 Setting the context Presentation on India-EU migration flows and trends and migration and mobility dialogues –Dr. Meera Sethi and Dr. Deoblina Kundu, Associate Professor, NIUA Presentation on future trends of migration affecting India and EU - Dr. TLS Bhaskar, Chief Administrative Officer, India Centre for Migration Overview of Various Dimensions of India-EU Migration, Dr. Rupa Chanda, Professor, Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore India-EU technical project - Ms. Seeta Sharma, Technical Officer ILO, Mr. Naozad Hodiwala, Project Manager ICMPD Local Partner Implementing Partner Implementing Partner India –EU Common Agenda on Migration and Mobility India-EU Cooperation and Dialogue on Migration and Mobility Project 12:15 -13:30 Session 1: Regular migration & Well-Managed Mobility Moderator: Dr. Gulshan Sachdeva, Professor Jawahalal Nehru University Speakers: Perspectives from the EU EU legal migration as part of comprehensive migration policy – Ms. -

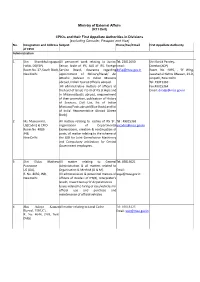

(RTI Cell) Cpios and Their First Appellate Authorities in Divisions

Ministry of External Affairs (RTI Cell) CPIOs and their First Appellate Authorities in Divisions [excluding Consular, Passport and Visa] No. Designation and Address Subject Phone/Fax/Email First Appellate Authority of CPIO Administration 1. Shri Shambhulingappa All personnel work relating to Junior, Tel: 23011650 Shri Kartik Pandey, Hakki, DS(FSP) Senior, Scale of IFS, JAG of IFS, Foreign Email: Director(ADP) Room No. 37, South Block, Service Board, clearance regarding [email protected] Room. No. 4095, , ‘B’ Wing, New Delhi appointment of Military/Naval/ Air Jawaharlal Nehru Bhawan, 23-D, Attache /Adviser in Indian Missions Janpath, New Delhi abroad, Indian Tourist Officers abroad. Tel: 49015363 All administrative matters of officers at Fax:49015364 the level of Grade I to IV of IFS at Hqrs and Email: [email protected] in Missions/posts abroad, empanelment of their promotion, publication of History of Services, Civil List, list of Indian Missions/Posts abroad (Blue Book) and list of India’ Representative Abroad (Green Book). 2 Ms. Manusmriti, All matters relating to cadres of IFS 'B' , Tel : 49015368 US(Cadre) & CPIO organisation of Departmental [email protected] Room No. 4086 Examinations, creation & continuation of JNB, posts, all matter relating to the scheme of New Delhi the GOI for Joint Consultative Machinery and Compulsory arbitration for Central Government employees. 3 Shri Eldos Mathew All matter relating to General Tel: 49016621 Punnoose Administration & all matters related to US (GA), Organisation & Method (O & M). Email:- R. No. 4050, JNB, All administrative & personnel matters of [email protected] New Delhi officers of Grade-I of IFS(B), Interpreter’s Grade, Inward Group ‘A’ deputationists. -

Questioning the Role of the Indian Administrative Service in National Integration

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal Free-Standing Articles | 2008 Questioning the Role of the Indian Administrative Service in National Integration Dalal Benbabaali Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/samaj/633 DOI: 10.4000/samaj.633 ISSN: 1960-6060 Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic reference Dalal Benbabaali, “Questioning the Role of the Indian Administrative Service in National Integration”, South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal [Online], Free-Standing Articles, Online since 05 September 2008, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/633 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/samaj.633 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal Benbabaali, Dalal (2008) ‘Questioning the Role of the Indian Administrative Service in National Integration’, South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, URL : http://samaj.revues.org/document 633.html. To quote a passage, use paragraph (§). Questioning the Role of the Indian Administrative Service in National Integration Dalal Benbabaali Abstract. After Independence, the Indian Administrative Service was expected to promote national integration, from a social as well as a spatial point of view. Yet, despite the reservation policy, this elite body lacks representativeness. The partisanship of IAS officers along caste, religious and ethnic lines has further reduced their efficiency as a binding force of the nation. Being an All- India Service, the IAS encourages the spatial mobility of its members, which is not always welcome by officers posted in far-off states or in disturbed areas. In these places, the vacancy of postings in the higher administration is a sign of desertion that is contrary to the IAS mission of territorial integration.