Sos Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NPWS Pocket Guide 3E (South Coast)

SOUTH COAST 60 – South Coast Murramurang National Park. Photo: D Finnegan/OEH South Coast – 61 PARK LOCATIONS 142 140 144 WOLLONGONG 147 132 125 133 157 129 NOWRA 146 151 145 136 135 CANBERRA 156 131 148 ACT 128 153 154 134 137 BATEMANS BAY 139 141 COOMA 150 143 159 127 149 130 158 SYDNEY EDEN 113840 126 NORTH 152 Please note: This map should be used as VIC a basic guide and is not guaranteed to be 155 free from error or omission. 62 – South Coast 125 Barren Grounds Nature Reserve 145 Jerrawangala National Park 126 Ben Boyd National Park 146 Jervis Bay National Park 127 Biamanga National Park 147 Macquarie Pass National Park 128 Bimberamala National Park 148 Meroo National Park 129 Bomaderry Creek Regional Park 149 Mimosa Rocks National Park 130 Bournda National Park 150 Montague Island Nature Reserve 131 Budawang National Park 151 Morton National Park 132 Budderoo National Park 152 Mount Imlay National Park 133 Cambewarra Range Nature Reserve 153 Murramarang Aboriginal Area 134 Clyde River National Park 154 Murramarang National Park 135 Conjola National Park 155 Nadgee Nature Reserve 136 Corramy Regional Park 156 Narrawallee Creek Nature Reserve 137 Cullendulla Creek Nature Reserve 157 Seven Mile Beach National Park 138 Davidson Whaling Station Historic Site 158 South East Forests National Park 139 Deua National Park 159 Wadbilliga National Park 140 Dharawal National Park 141 Eurobodalla National Park 142 Garawarra State Conservation Area 143 Gulaga National Park 144 Illawarra Escarpment State Conservation Area Murramarang National Park. Photo: D Finnegan/OEH South Coast – 63 BARREN GROUNDS BIAMANGA NATIONAL PARK NATURE RESERVE 13,692ha 2,090ha Mumbulla Mountain, at the upper reaches of the Murrah River, is sacred to the Yuin people. -

Australasian Bat Society Newsletter

The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter Number 21 November 2003 ABS Website: http://abs.ausbats.org.au ABS Listserver: [email protected] ISSN 1448-5877 The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter, Number 21, Nov 2003 – Instructions for Contributors – The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter will accept contributions under one of the following two sections: Research Papers, and all other articles or notes. There are two deadlines each year: 31 st March for the April issue, and 31 st October for the November issue. The Editor reserves the right to hold over contributions for subsequent issues of the Newsletter , and meeting the deadline is not a guarantee of immediate publication. Opinions expressed in contributions to the Newsletter are the responsibility of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Australasian Bat Society, its Executive or members. For consistency, the following guidelines should be followed: • Emailed electronic copy of manuscripts or articles, sent as an attachment, is the preferred method of submission. Manuscripts can also be sent on 3½” floppy disk preferably in IBM format. Faxed and hard copy manuscripts will be accepted but reluctantly! Please send all submissions to the Newsletter Editor at the email or postal address below. • Electronic copy should be in 11 point Arial font, left and right justified with 16 mm left and right margins. Please use Microsoft Word; any version is acceptable. • Manuscripts should be submitted in clear, concise English and free from typographical and spelling errors. Please leave two spaces after each sentence. • Research Papers should include: Title; Names and addresses of authors; Abstract (approx. -

Underpinnings of Fire Management for Biodiversity Conservation in Reserves A

Underpinnings of fire management for biodiversity conservation in reserves A. Malcolm Gill Fire and adaptive management report no. 73 Underpinnings of fire management for biodiversity conservation in reserves Fire and adaptive management report no. 73 A. Malcolm Gill CSIRO Plant Industry, GPO Box 1600, Canberra, ACT 2601 Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200 Bushfire Cooperative Research Centre, Albert St, East Melbourne, Vic 3002 Underpinnings of fire management for biodiversity conservation in reserves Published by the Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment Melbourne, November 2008 © The State of Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment 2008 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne. Printed by Stream Solutions Printed on 100% Recycled paper ISBN: 978-1-74208-868-6 (print); ISBN: 978-1-74208-869-3 (online) For more information contact the DSE Customer Service Centre 136 186 Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Cover photograph: Malcolm Gill Acknowledgements This contribution was initially inspired by senior officers of the Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) – especially Mike Leonard. His encouragement, and that of Gary Morgan and Dr Kevin Tolhurst (University of Melbourne, Victoria), is greatly appreciated. -

Annual Report 2001-2002 (PDF

2001 2002 Annual report NSW national Parks & Wildlife service Published by NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service PO Box 1967, Hurstville 2220 Copyright © National Parks and Wildlife Service 2002 ISSN 0158-0965 Coordinator: Christine Sultana Editor: Catherine Munro Design and layout: Harley & Jones design Printed by: Agency Printing Front cover photos (from top left): Sturt National Park (G Robertson/NPWS); Bouddi National Park (J Winter/NPWS); Banksias, Gibraltar Range National Park Copies of this report are available from the National Parks Centre, (P Green/NPWS); Launch of Backyard Buddies program (NPWS); Pacific black duck 102 George St, The Rocks, Sydney, phone 1300 361 967; or (P Green); Beyers Cottage, Hill End Historic Site (G Ashley/NPWS). NPWS Mail Order, PO Box 1967, Hurstville 2220, phone: 9585 6533. Back cover photos (from left): Python tree, Gossia bidwillii (P Green); Repatriation of Aboriginal remains, La Perouse (C Bento/Australian Museum); This report can also be downloaded from the NPWS website: Rainforest, Nightcap National Park (P Green/NPWS); Northern banjo frog (J Little). www.npws.nsw.gov.au Inside front cover: Sturt National Park (G Robertson/NPWS). Annual report 2001-2002 NPWS mission G Robertson/NPWS NSW national Parks & Wildlife service 2 Contents Director-General’s foreword 6 3Conservation management 43 Working with Aboriginal communities 44 Overview Joint management of national parks 44 Mission statement 8 Aboriginal heritage 46 Role and functions 8 Outside the reserve system 47 Customers, partners and stakeholders -

Sydney Gateway

Sydney Gateway State Significant Infrastructure Scoping Report BLANK PAGE Sydney Gateway road project State Significant Infrastructure Scoping Report Roads and Maritime Services | November 2018 Prepared by the Gateway to Sydney Joint Venture (WSP Australia Pty Limited and GHD Pty Ltd) and Roads and Maritime Services Copyright: The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of NSW Roads and Maritime Services. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of NSW Roads and Maritime Services constitutes an infringement of copyright. Document controls Approval and authorisation Title Sydney Gateway road project State Significant Infrastructure Scoping Report Accepted on behalf of NSW Fraser Leishman, Roads and Maritime Services Project Director, Sydney Gateway by: Signed: Dated: 16-11-18 Executive summary Overview Sydney Gateway is part of a NSW and Australian Government initiative to improve road and freight rail transport through the important economic gateways of Sydney Airport and Port Botany. Sydney Gateway is comprised of two projects: · Sydney Gateway road project (the project) · Port Botany Rail Duplication – to duplicate a three kilometre section of the Port Botany freight rail line. NSW Roads and Maritime Services (Roads and Maritime) and Sydney Airport Corporation Limited propose to build the Sydney Gateway road project, to provide new direct high capacity road connections linking the Sydney motorway network with Sydney Kingsford Smith Airport (Sydney Airport). The location of Sydney Gateway, including the project, is shown on Figure 1.1. Roads and Maritime has formed the view that the project is likely to significantly affect the environment. On this basis, the project is declared to be State significant infrastructure under Division 5.2 of the NSW Environmental Planning & Assessment Act 1979 (EP&A Act), and needs approval from the NSW Minister for Planning. -

The Impact of the European Rabbit (Oryctolagus Cuniculus L.) on Diversity of Vascular Plants in Semi-Arid Woodlands

The impact of the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus L.) on diversity of vascular plants in semi-arid woodlands NSW Department of Land and Water Conservation The impact of the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus L.) on diversity of vascular plants in semi-arid woodlands A consultancy report for WEST 2000Plus Prepared by: David Eldridge NSW Department of Land and Water Conservation The impact of the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus L.) on diversity of vascular plants in semi-arid woodlands report Acknowledgments I am grateful to the following people for their hard work and assistance with field data collection: James Val, Scott Jaensch, Ron Rees, Sharee Bradford, Daryl Laird and Peter Connellan. James Val and Bruce Cooper provided comments on an earlier draft. Special thanks are due to Ron Rees (WEST 2000Plus) who has worked tirelessly to promote rabbit control in the Western Division. Published by: Centre for Natural Resources New South Wales Department of Land and Water Conservation Parramatta March 2002 ? NSW Government ISBN 0 000 0000 0 ISSN 0000 0000 CNR2002.006 NSW Department of Land and Water Conservation ii The impact of the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus L.) on diversity of vascular plants in semi-arid woodlands report Contents Page Executive Summary.....................................................................................................................v Terms of Reference ..........................................................................................................v 1. Background......................................................................................................................1 -

NPWS Annual Report 2000-2001 (PDF

Annual report 2000-2001 NPWS mission NSW national Parks & Wildlife service 2 Contents Director-General’s foreword 6 3 Conservation management 43 Working with Aboriginal communities 44 Overview 8 Joint management of national parks 44 Mission statement 8 Performance and future directions 45 Role and functions 8 Outside the reserve system 46 Partners and stakeholders 8 Voluntary conservation agreements 46 Legal basis 8 Biodiversity conservation programs 46 Organisational structure 8 Wildlife management 47 Lands managed for conservation 8 Performance and future directions 48 Organisational chart 10 Ecologically sustainable management Key result areas 12 of NPWS operations 48 Threatened species conservation 48 1 Conservation assessment 13 Southern Regional Forest Agreement 49 NSW Biodiversity Strategy 14 Caring for the environment 49 Regional assessments 14 Waste management 49 Wilderness assessment 16 Performance and future directions 50 Assessment of vacant Crown land in north-east New South Wales 19 Managing our built assets 51 Vegetation surveys and mapping 19 Buildings 51 Wetland and river system survey and research 21 Roads and other access 51 Native fauna surveys and research 22 Other park infrastructure 52 Threat management research 26 Thredbo Coronial Inquiry 53 Cultural heritage research 28 Performance and future directions 54 Conservation research and assessment tools 29 Managing site use in protected areas 54 Performance and future directions 30 Performance and future directions 54 Contributing to communities 55 2 Conservation planning -

Matters of National Environmental Significance Report

Gold Coast Quarry EIS ATTACHMENT D SITE ACCESS PLANS September 2013 Cardno Chenoweth 99 Gold Coast Quarry EIS ATTACHMENT E SITE TOPOGRAPHY September 2013 Cardno Chenoweth 99 Pacific Motorway 176 176 RP899491 RP899491 N 6889750 m E 539000 m E 539250 m E 539500 m E 539750 m E 540000 m E 540250 m E 540500 m E 540750 m E 541000 m E 541250 m E 541500 m N 6889750 m 903 905 SP210678 SP245339 144 905 WD4736 SP245339 N 6889500 m N 6889500 m Old Coach Road 22 SP238363 N 6889250 m N 6889250 m N 6889000 m N 6889000 m 103 105 5 SP127528 SP144215 RP162129 Barden Ridge Road 103 SP127528 Chesterfield Drive N 6888750 m N 6888750 m 1 RP106195 4 RP162129 RP853810 RP162129 927 6 4 5 SP220598 RP853810 3 RP854351 RP162129 2 N 6888500 m 5 N 6888500 m RP803474 SP105668 12 WD6568 SP105668 7 11 1 SP187063 105 2 3 F:\Jobs\1400\1454 Cardno Boral_Tallebudgera GCQ\000 Generic\Drawings\1454_017 Topography_aerial.dwg 15 SP144215 RP812114 RP803474 RP903701 1 Tallebudgera Creek Road 3 RP148506 FILE NAME: 13 RP803474 SP105668 901 RP907357 2 3 RP803474 SP187063 RP164840 6 N 6888250 m N 6888250 m 14 SP105668 600 SP251058 3 JOB SUB #: 901 1 SP145343 RP205290 RP148504 2 27 Samuel Drive 104 RP811199 RP190638 RP180320 2 8 October 2012 30 2 RP180320 SP150481 N 6888000 m RP838498 31 N 6888000 m RP180321 E 539000 m E 539250 m E 539500 m E 539750 m E 540000 m E 540250 m E 540500 m E 540750 m E 541000 m E 541250 m E 541500 m CREATED: REV DESCRIPTION DATE BY Legend: PROJECT: TITLE: Site Boundary Tallebudgera Figure 13 - Aerial Photo and Topography Photography: Nearmap. -

South Coast Shorebird Recovery Newsletter

SOUTH COAST SHOREBIRD RECOVERY NEWSLETTER 2008/09 Season This Season in Shorebirds species has declined especially in Victoria. Our 28 breeding pairs fledged at least 7 chicks. We will con- The shorebird breeding season kicked off in August tinue to monitor this species in southern NSW. The with Hooded Plover’s nesting first in the South Coast endangered Hooded Plovers had one of their best sea- Region (SCR). The ex Shorebird Recovery Coordina- sons yet with 14 chicks fledged from the 16 breeding tors, Mike and Jill, found this early nest on Racecourse pairs. Furthermore we had our first signs of recruit- Beach in Ulladulla. Soon after this discovery Jodie ment early in the season with 4 young adults present in started work again at the local NPWS office and the SCR, presumed last seasons fledglings returning. ‘Hoodie’ nests were popping up everywhere. Down on Two paired up and even nested together. Exciting! the Far South Coast (FSCR) Amy’s ‘Hoodies’ were late starters with the first nest not found til late September, Pied Oystercatchers nested in most estuaries along the but she was very busy anyway with all the nesting Pied south coast. A total of 38 breeding pairs incubated 90 Oystercatchers. The FSCR holds 70% of our Pied eggs, hatched 46 chicks and fledged 22. Overall a good breeding pairs. Then it was October and the Little result but breeding success was reduced compared with Terns started arriving. The intense summer nesting previous seasons. The Sooty Oystercatchers, nested on frenzy really began. Meanwhile the Sooty Oyster- all eight offshore islands as with previous years. -

Vegetation and Floristics of Ironbark Nature Reserve & Bornhardtia

Vegetation and Floristics of Ironbark Nature Reserve & Bornhardtia Voluntary Conservation Area Dr John T. Hunter (aka Thomas D. McGann) August 2002 © J.T.Hunter 2002 75 Kendall Rd, Invergowrie NSW, 2350 Ph. & Fax: (02) 6775 2452 Email: [email protected] A Report to the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service i Vegetation of Ironbark & Bornhardtia Summary The vegetation of Ironbark Nature Reserve and the Bornhardtia Voluntary Conservation Area is described and mapped (scale 1:25 000). Eleven communities are defined based on classification (Kulczynski association) with further sub-assemblages described. These eleven communities were mapped based on ground truthing, air photo interpretation and landform. One community is listed as Endangered on state and federal acts (TSC & EPB&C Acts), three are considered here to be vulnerable and all others are considered to be poorly or inadequately reserved across their range. Most communities are of woodland and open forest structure. The communities show considerable variation and intergrade along common boundaries and in particular on intermediate soil types. Drainage, Easting, Soil Depth, Physiography and protection from the North were the major correlative influences on community distribution, however Northing and Rock Type were also strongly correlated. A total of 477 vascular plant taxa were found from 93 families and 269 genera. At least 39 species are considered of significance, 30 are of regional significance and a further nine are of state or national significance. Two species are listed on the TSC Act, one as Endangered and one as Vulnerable nine are RoTAP listed species or are listed under this criteria in other publications. -

Part 1 Plant Communities of the NSW Western Plains

383 New South Wales Vegetation Classification and Assessment: Part 1 Plant communities of the NSW Western Plains J.S. Benson*, C.B. Allen*, C. Togher** and J. Lemmon*** *Science and Public Programs, Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust, Sydney, NSW 2000, AUSTRALIA. ** GIS Section NSW Department of Environment & Conservation, PO Box 1967 Hurstville, NSW 2220; ***Environment & Development Department, Wollongong City Council, Locked Bag 8821, South Coast Mail Centre, NSW 2521. Corresponding author email: [email protected] Abstract: For the Western Plains of New South Wales, 213 plant communities are classified and described and their protected area and threat status assessed. The communities are listed on the NSW Vegetation Classification and Assessment database (NSWVCA). The full description of the communities is placed on an accompanying CD together with a read-only version of the NSWVCA database. The NSW Western Plains is 45.5 million hectares in size and covers 57% of NSW. The vegetation descriptions are based on over 250 published and unpublished vegetation surveys and maps produced over the last 50 years (listed in a bibliography), rapid field checks and the expert knowledge on the vegetation. The 213 communities occur over eight Australian bioregions and eight NSW Catchment Management Authority areas. As of December 2005, 3.7% of the Western Plains was protected in 83 protected areas comprising 62 public conservation reserves and 21 secure property agreements. Only one of the eight bioregions has greater than 10% of its area represented in protected areas. 31 or 15% of the communities are not recorded from protected areas. 136 or 64% have less than 5% of their pre-European extent in protected areas. -

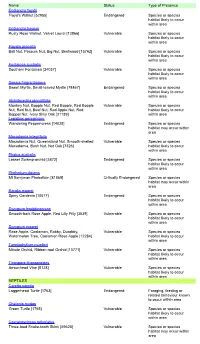

Name Status Type of Presence Floyd's Walnut

Name Status Type of Presence Endiandra floydii Floyd's Walnut [52955] Endangered Species or species habitat likely to occur within area Endiandra hayesii Rusty Rose Walnut, Velvet Laurel [13866] Vulnerable Species or species habitat likely to occur within area Floydia praealta Ball Nut, Possum Nut, Big Nut, Beefwood [15762] Vulnerable Species or species habitat likely to occur within area Fontainea australis Southern Fontainea [24037] Vulnerable Species or species habitat likely to occur within area Gossia fragrantissima Sweet Myrtle, Small-leaved Myrtle [78867] Endangered Species or species habitat likely to occur within area Hicksbeachia pinnatifolia Monkey Nut, Bopple Nut, Red Bopple, Red Bopple Vulnerable Species or species Nut, Red Nut, Beef Nut, Red Apple Nut, Red habitat likely to occur Boppel Nut, Ivory Silky Oak [21189] within area Lepidium peregrinum Wandering Pepper-cress [14035] Endangered Species or species habitat may occur within area Macadamia integrifolia Macadamia Nut, Queensland Nut, Smooth-shelled Vulnerable Species or species Macadamia, Bush Nut, Nut Oak [7326] habitat likely to occur within area Phaius australis Lesser Swamp-orchid [5872] Endangered Species or species habitat likely to occur within area Phebalium distans Mt Berryman Phebalium [81869] Critically Endangered Species or species habitat may occur within area Randia moorei Spiny Gardenia [10577] Endangered Species or species habitat likely to occur within area Syzygium hodgkinsoniae Smooth-bark Rose Apple, Red Lilly Pilly [3539] Vulnerable Species or species