Cinematic Narratives: Transatlantic Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Schulhoffs Flammen

ERWIN SCHULHOFF Zur Wiederentdeckung seiner Oper „Flammen“ Kloster-Sex, Nekrophilie, alles eins Schulhoffs "Flammen". Entdeckung im "Don Juan"-Zyklus des Theaters an der Wien. Am Anfang war das Ich. Dann das Es. Und das Überich erst, lieber Himmel, da hat sich die Menschheit etwas eingebrockt, als sie alle Dämme brechen ließ und den Kaiser wie den Lieben Gott gute Männer sein ließen. Nichts klärt uns über die Befindlichkeit der Sigmund- Freud-Generation besser auf als die Kunst der Ära zwischen 1900 und 1933, ehe die Politik - wie zuvor schon in der sowjetischen Diktatur - auch in 9. August 2006 SINKOTHEK Deutschland die ästhetischen Koordinatensysteme diktierte. Beobachtet man in Zeiten, wie die unsre eine ist, die diversen sexuellen, religiösen und sonstigen Wirrnisse, von denen die damalige Menschheit offenbar fasziniert war, fühlt man sich, wie man im Kabarett so schön sang, "apres". Sex im Kloster, Nekrophilie, alles eins. Tabus kennen wir nicht mehr; jedenfalls nicht in dieser Hinsicht. Das Interesse an einem Werk wie "Flammen", gedichtet von Max Brod frei nach Karel Josef Benes, komponiert von dem 1942 von den Nationalsozialisten ermordeten Erwin Schulhoff, ist denn auch vorrangig musikhistorischer Natur. Es gab 9. August 2006 SINKOTHEK mehr zwischen Schönberg und Lehar als unsere Schulweisheit sich träumen lässt. Erwin Schulhoff war ein Meister im Sammeln unterschiedlichster Elemente aus den Musterkatalogen des Im- wie des Expressionismus. Er hatte auch ein Herz für die heraufdämmernde Neue Sachlichkeit, ohne deshalb Allvater Wagner zu verleugnen. Seine "Flammen", exzellent instrumentiert mit allem Klingklang von Harfe, Glocke und Celesta, das jeglichen alterierten Nonenakkord wie ein Feuerwerk schillern und glitzern lässt, tönen mehr nach Schreker als nach Hindemith - auch wenn das einleitende Flötensolo beinahe den keusch-distanzierten Ton der "Cardillac"- Musik atmet. -

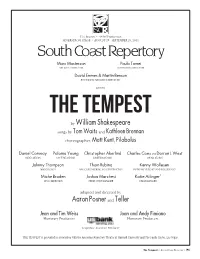

By William Shakespeare Aaron Posner and Teller

51st Season • 483rd Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / AUGUST 29 - SEPTEMBER 28, 2014 Marc Masterson Paula Tomei ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR David Emmes & Martin Benson FOUNDING ARTISTIC DIRECTORS presents THE TEMPEST by William Shakespeare songs by Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan choreographer, Matt Kent, Pilobolus Daniel Conway Paloma Young Christopher Akerlind Charles Coes AND Darron L West SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN Johnny Thompson Thom Rubino Kenny Wollesen MAGIC DESIGN MAGIC ENGINEERING AND CONSTRUCTION INSTRUMENT DESIGN AND WOLLESONICS Miche Braden Joshua Marchesi Katie Ailinger* MUSIC DIRECTION PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER adapted and directed by Aaron Posner and Teller Jean and Tim Weiss Joan and Andy Fimiano Honorary Producers Honorary Producers Corporate Associate Producer THE TEMPEST is presented in association with the American Repertory Theater at Harvard University and The Smith Center, Las Vegas. The Tempest • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY • P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS Prospero, a magician, a father and the true Duke of Milan ............................ Tom Nelis* Miranda, his daughter .......................................................................... Charlotte Graham* Ariel, his spirit servant .................................................................................... Nate Dendy* Caliban, his adopted slave .............................. Zachary Eisenstat*, Manelich Minniefee* Antonio, Prospero’s brother, the usurping Duke of Milan ......................... Louis Butelli* Gonzala, -

Liste Dvd Consult

titre réalisateur année durée cote Amour est à réinventer (L') * 2003 1 h 46 C 52 Animated soviet propaganda . 1 , Les impérialistes américains * 1933-2006 1 h 46 C 58 Animated soviet propaganda . 2 , Les barbares facistes * 1941-2006 2 h 16 C 56 Animated soviet propaganda . 3 , Les requins capitalistes * 1925-2006 1 h 54 C 59 Animated soviet propaganda . 4 , Vers un avenir brillant, le communisme * 1924-2006 1 h 54 C 57 Animatix : une sélection des meilleurs courts-métrages d'animation française. * 2004 57 min. C 60 Animatrix * 2003 1 h 29 C 62 Anime story * 1990-2002 3 h C 61 Au cœur de la nuit = Dead of night * 1945 1 h 44 C 499 Autour du père : 3 courts métrages * 2003-2004 1 h 40 C 99 Avant-garde 1927-1937, surréalisme et expérimentation dans le cinéma belge * 1927-1937 1 h 30 C 100 (dvd 1&2) Best of 2002 * 2002 1 h 12 C 208 Caméra stylo. Vol. 1 * 2001-2005 2 h 25 C 322 Cinéma différent = Different cinema . 1 * 2005 1 h 30 C 461 Cinéma documentaire (Le) * 2003 2 h 58 C 462 Documentaire animé (Le). 1, C'est la politique qui fait l'histoire : 9 films * 2003-2012 1 h 26 C 2982 Du court au long. Vol. 1 * 1973-1986 1 h 52 C 693 Fellini au travail * 1960-1975 3 h 20 C 786 (dvd 1&2) Filmer le monde : les prix du Festival Jean Rouch. 01 * 1947-1984 2 h 40 C 3176 Filmer le monde : les prix du Festival Jean Rouch. -

Carlos Castaneda – a Separate Reality

“A Separate Reality: Further Conversations with don Juan” - ©1971 by Carlos Castaneda Contents • Introduction • Part One: The Preliminaries of 'Seeing' o Chapter 1. o Chapter 2. o Chapter 3. o Chapter 4. o Chapter 5. o Chapter 6. o Chapter 7. • Part Two: The Task of 'Seeing' o Chapter 8. o Chapter 9. o Chapter 10. o Chapter 11. o Chapter 12. o Chapter 13. o Chapter 14. o Chapter 15. o Chapter 16. o Chapter 17. • Epilogue Introduction Ten years ago I had the fortune of meeting a Yaqui Indian from northwestern Mexico. I call him "don Juan." In Spanish, don is an appellative used to denote respect. I made don Juan's acquaintance under the most fortuitous circumstances. I had been sitting with Bill, a friend of mine, in a bus depot in a border town in Arizona. We were very quiet. In the late afternoon, the summer heat seemed unbearable. Suddenly he leaned over and tapped me on the shoulder. "There's the man I told you about," he said in a low voice. He nodded casually toward the entrance. An old man had just walked in. "What did you tell me about him?" I asked. "He's the Indian that knows about peyote. Remember?" I remembered that Bill and I had once driven all day looking for the house of an "eccentric" Mexican Indian who lived in the area. We did not find the man's house and I had the feeling that the Indians whom we had asked for directions had deliberately misled us. Bill had told me that the man was a "yerbero," a person who gathers and sells medicinal herbs, and that he knew a great deal about the hallucinogenic cactus, peyote. -

The White Possession of Detroit in Jim Jarmusch’S Only Lovers Left Alive Matthew J

1 ‘Your Wilderness’: The White Possession of Detroit in Jim Jarmusch’s Only Lovers Left Alive Matthew J. Irwin American Studies, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico ([email protected]) Abstract After a decade of accelerated disinvestment and depopulation, Detroit (re)appeared in the national imaginary as “urban frontier” open for (re)settlement by (mostly white) creative entrepreneurs. Recently, scholars have begun to address the ways in which this frontier rhetoric underscores a settler colonial discourse of erasure for the purpose of land acquisition and (re)development. The post-industrial landscape assumes a veil of wildness and abandon that arouses settler colonial desire for land through a narrative of white return that relies not just on a notion black criminality or ineptitude, but also more fundamentally on an assumption of deferred white possession. Though this work has productively described the settler colonial conditions of racialized (re)development in the Motor City, it has remained tied to a binary of black/white relations. It has ignored, therefore, white possession as a process that mythologizes and absorbs Indigenous history and delegitimizes Indigenous people. In this paper I read Jim Jarmusch’s 2014 vampire film Only Lovers Left Alive as a “landscape of monstrosity” that inadvertently and momentarily recovers Indigenous and African American presence in moments of erasure and absence. Where the film centers on a white vampire elite and suggests a “zombie” white working class, the Detroit landscape recovers African Americans through their invisibility (as ghosts) and Native Americans through savage or regressed nature (as werewolves). More broadly, I argue that Only Lovers Left Alive actively participates in an ideological process of (re)settlement that disguises land speculation (and its inherently disruptive cycles of uneven development) in a renewed frontier mythology. -

AF Yo Bill Murray 051016.Indd

Primera edición, noviembre 2016 © Marta Jiménez © Ilustraciones: sus autores © Diseño de cubierta e ilustraciones en Momentos Murray: Pedro Peinado © Diseño de colección: Pedro Peinado www.pedropeinado.com Edición de Antonio de Egipto y Marga Suárez www.estonoesuntipo.com Bandaàparte Editores www.bandaaparteeditores.com ISBN 978-84-944086-8-7 Depósito Legal CO-1591-2016 Este libro está bajo Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento – NoComercial – SinObraDerivada (by-nc-nd): No se permite un uso comercial de la obra original ni la generación de obras derivadas. +info: www.es.creativecommons.org Impresión: Gráficas La Paz. www.graficaslapaz.com El papel empleado para la impresión de este libro proviene de bosques gestionados de manera sostenible, desde el punto de vista medioambiental, económico y social. Impreso en España A mi padre y a mi madre, que no recuerdan dónde han visto a Bill Murray RZA: Tú eres Bill Murray. Bill Murray: Lo sé, pero no se lo digas a nadie. GZA: ¿Qué quieres decir con que no lo cuente, Bill Murray? La gente vendrá, te verá, eres Bill Murray, es obvio, a menos que uses un disfraz o algo. Bill Murray: Estoy disfrazado. GZA: Maldición, eso es terrible, amigo. (Coffee and Cigarettes. Jim Jarmusch, 2004) THE EVERYDAY MAN por Javier del Pino Un humorista muy conocido suele decir que hay dos tipos de có- micos: los que tienen gracia y los que tienen que trabajar para tener gracia. Lo dice con resignación, porque pertenece a la segunda cate- goría. Nada le hubiera gustado más que haber nacido con las carac- terísticas indescriptibles que definen a ese minúsculo grupo de per- sonas que, en un universo tan multitudinario, tienen la pintoresca virtud de expresar sentimientos o provocar reacciones sin decir nada y sin hacer nada. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

Friday 14 February 2020, London. BFI Southbank's TILDA SWINTON

Friday 14 February 2020, London. BFI Southbank’s TILDA SWINTON season, programmed in partnership with the performer and filmmaker herself, will run from 1 – 18 March 2020, celebrating the extraordinary, convention-defying career of one of cinema’s finest and most deft chameleons. The BFI today announce that a number of Swinton’s closest collaborators will join her on stage during the season to speak about their work together including Wes Anderson (Isle of Dogs, The French Dispatch, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Moonrise Kingdom), Bong Joon-ho (Snowpiercer, Okja), Sally Potter (Orlando) and Joanna Hogg (The Souvenir, Caprice). Also announced today is Tilda Swinton’s Film Equipment (28 February – 26 April) a free exhibit to accompany the season which has been curated in close collaboration with BFI and Swinton’s personal archive. Alongside a programme of feature film screenings, shorts and personal favourites, the season will include Tilda Swinton in Conversation with host Mark Kermode on 3 March, during which Swinton will look back on her wide- reaching career as a performer across independent and Hollywood cinema, as well as producer, director and general ally of maverick free spirits everywhere. On the same evening will be Tilda Swinton and Wes Anderson on stage: A Magical Tour of Cinema – a unique chance to hear from two of the most fervent disciples of the church of make believe, as Swinton and Anderson take to the BFI stage to discuss their many collaborations and their film passions. The event will offer a glimpse into their intimate partnership as the two long-time co-conspirators and voracious cinephiles select and explore personal favourite gems from throughout cinema’s history. -

An Examination of Stylistic Elements in Richard Strauss's Wind Chamber Music Works and Selected Tone Poems Galit Kaunitz

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 An Examination of Stylistic Elements in Richard Strauss's Wind Chamber Music Works and Selected Tone Poems Galit Kaunitz Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC AN EXAMINATION OF STYLISTIC ELEMENTS IN RICHARD STRAUSS’S WIND CHAMBER MUSIC WORKS AND SELECTED TONE POEMS By GALIT KAUNITZ A treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Galit Kaunitz defended this treatise on March 12, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Eric Ohlsson Professor Directing Treatise Richard Clary University Representative Jeffrey Keesecker Committee Member Deborah Bish Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii This treatise is dedicated to my parents, who have given me unlimited love and support. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee members for their patience and guidance throughout this process, and Eric Ohlsson for being my mentor and teacher for the past three years. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ vi Abstract -

The Hell Scene and Theatricality in Man and Superman

233 The Amphitheatre and Ann’s Theatre: The Hell Scene and Theatricality in Man and Superman Yumiko Isobe Synopsis: Although George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman (1903) is one of his most important dramatic works, it has seldom been staged. This is because, in terms of content and direction, there are technical issues that make it difficult to stage. In particular, Act Three features a dream in Hell, where four dead characters hold a lengthy philosophical symposium, has been considered independent of the main plot of John Tanner and Ann Whitefield. Tanner’s dream emphatically asserts its theatricality by the scenery, the amphitheatre in the Spanish desert where Tanner dozes off. The scene’s geography, which has not received adequate attention, indicates the significance of the dream as a theatre for the protagonist’s destiny with Ann. At the same time, it suggests that the whole plot stands out as a play by Ann, to which Tanner is a “subject.” The comedy thus succeeds in expressing the playwright’s philosophy of the Superman through the play-within-a- play and metatheatre. Introduction Hell in the third act of Man and Superman: A Comedy and a Philosophy (1903) by George Bernard Shaw turns into a philosophical symposium, as the subtitle of the play suggests, and this intermediate part is responsible for the difficulties associated with the staging of the play. The scene, called “the Hell scene” or “Don Juan in Hell,” has been cut out of performances of the whole play, and even performed separately; however, the interlude by itself has attracted considerable attention, not only from stage managers and actors, but also from critics, provoking a range of multi-layered examinations. -

Magisterarbeit / Master's Thesis

MAGISTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Magisterarbeit / Title of the Master‘s Thesis MUSIK IST STENOGRAPHIE DER GEFÜHLE. Ein Versuch der Untersuchung der durch Musik und musikalischer Untermalung hervorgerufenen bzw. gestützten emotionalen Kommunikation in Filmen verfasst von / submitted by Katharina Köhle, bakk. phil. angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2019 / Vienna 2019 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / UA 066 841 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Publizistik- und Kommunikationswissenschaft degree programme as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Fritz (Friedrich) Hausjell INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1. EINFÜHRUNG _____________________________________________ S. 4 2. THEMENGRUNDLAGEN _____________________________________ S. 6 2.1. FILM ..................................................................................................................... S. 6 2.1.1. Definition ............................................................................................... S. 6 2.1.2. Historischer Abriss ................................................................................. S. 14 2.1.3. Filmtheorie .............................................................................................. S. 18 2.2. MUSIK .................................................................................................................