The Failure of the Bush Administration to Ratify the Kyoto Protocol As a State Crime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Meantime, Thought You Might Enjoy the Ad That Provides a Bit More Truth in Advertising

Knutte, Caitlin From: Hendrickson, Cara Sent: Monday, March 21, 2016 8: 58 PM To: wendy Abrams Cc: Spillane, Ann M. Subject: Re: Exxon Document Thanks, Wendy. Best, Cara On Mar 21, 2016, at 6: 39 PM, wendy Abrams < wrote: I will forward this tomorrow. In the meantime, thought you might enjoy the ad that provides a bit more truth in advertising.. http:// youtu. be/ XhOezO s -Gs again, thank you for your time today. I cannot think of a more critical issue at a critical time; this could be a tipping point. Best, Wendy Begin forwarded message: From: " O' Neill, Christine M." < coneill2Alaw. pace. edu> Subject: Exxon Document Date: March 21, 2016 at 5: 45: 53 PM CDT To: Wendy Abrams < Hi Wendy, Bobby asked me to email the Exxon Mobil document that he sent to Eric Schneiderman. Unfortunately, it' s in my email archive folder and I can' t access it from home. Would it be okay if I sent to you tomorrow morning when I get to the office? Thanks, Christine Christine O' Neill Executive Assistant, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. Office: 914- 422- 4343 Cell: Knutte, Caitlin From: wendy abrams < Sent: Tuesday, March 22, 2016 9: 35 AM To: Spillane, Ann M.; Hendrickson, Cara Subject: Re: Madigan demands Peabody prove it has coal mine -closure money 1 Environment 1 thesouthern. com Attachments: ExxonMobilSchneidermanJan5FINAL. docx From Robert Kennedy. Jr. On Mar 22, 2016, at 8: 42 AM, Spillane, Ann M. < aspillane,ci atg. state. il. us> wrote: Thank you! And thank you for all of your time yesterday - that was really a helpful meeting. -

Open PDF File, 8.71 MB, for February 01, 2017 Appendix In

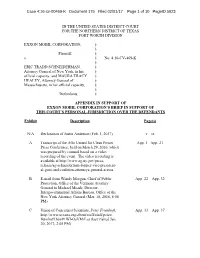

Case 4:16-cv-00469-K Document 175 Filed 02/01/17 Page 1 of 10 PageID 5923 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS FORT WORTH DIVISION EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION, § § Plaintiff, § v. § No. 4:16-CV-469-K § ERIC TRADD SCHNEIDERMAN, § Attorney General of New York, in his § official capacity, and MAURA TRACY § HEALEY, Attorney General of § Massachusetts, in her official capacity, § § Defendants. § APPENDIX IN SUPPORT OF EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION’S BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF THIS COURT’S PERSONAL JURISDICTION OVER THE DEFENDANTS Exhibit Description Page(s) N/A Declaration of Justin Anderson (Feb. 1, 2017) v – ix A Transcript of the AGs United for Clean Power App. 1 –App. 21 Press Conference, held on March 29, 2016, which was prepared by counsel based on a video recording of the event. The video recording is available at http://www.ag.ny.gov/press- release/ag-schneiderman-former-vice-president- al-gore-and-coalition-attorneys-general-across B E-mail from Wendy Morgan, Chief of Public App. 22 – App. 32 Protection, Office of the Vermont Attorney General to Michael Meade, Director, Intergovernmental Affairs Bureau, Office of the New York Attorney General (Mar. 18, 2016, 6:06 PM) C Union of Concerned Scientists, Peter Frumhoff, App. 33 – App. 37 http://www.ucsusa.org/about/staff/staff/peter- frumhoff.html#.WI-OaVMrLcs (last visited Jan. 20, 2017, 2:05 PM) Case 4:16-cv-00469-K Document 175 Filed 02/01/17 Page 2 of 10 PageID 5924 Exhibit Description Page(s) D Union of Concerned Scientists, Smoke, Mirrors & App. -

Anti-Reflexivity: the American Conservative Movement's Success

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249726287 Anti-reflexivity: The American Conservative Movement's Success in Undermining Climate Science and Policy Article in Theory Culture & Society · May 2010 DOI: 10.1177/0263276409356001 CITATIONS READS 360 1,842 2 authors, including: Riley E. Dunlap Oklahoma State University - Stillwater 369 PUBLICATIONS 25,266 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Climate change: political polarization and organized denial View project Tracking changes in environmental worldview over time View project All content following this page was uploaded by Riley E. Dunlap on 30 March 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Theory, Culture & Society http://tcs.sagepub.com Anti-reflexivity: The American Conservative Movement’s Success in Undermining Climate Science and Policy Aaron M. McCright and Riley E. Dunlap Theory Culture Society 2010; 27; 100 DOI: 10.1177/0263276409356001 The online version of this article can be found at: http://tcs.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/27/2-3/100 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Theory, Culture & Society can be found at: Email Alerts: http://tcs.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://tcs.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://tcs.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/27/2-3/100 Downloaded from http://tcs.sagepub.com at OKLAHOMA STATE UNIV on May 25, 2010 100-133 TCS356001 McCright_Article 156 x 234mm 29/03/2010 16:06 Page 100 Anti-reflexivity The American Conservative Movement’s Success in Undermining Climate Science and Policy Aaron M. -

Strategic Plan of the US Climate Change Science Program (Final

A Report by the Climate Change Science Program and the Subcommittee on Global Change Research CLIMATE CHANGE SCIENCE PROGRAM and SUBCOMMITTEE ON GLOBAL CHANGE RESEARCH James R. Mahoney Aristides Patrinos Department of Commerce Department of Energy National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Jacqueline Schafer Director, Climate Change Science Program U.S. Agency for International Development Chair, Subcommittee on Global Change Research Michael Slimak Environmental Protection Agency Ghassem Asrar,Vice Chair National Aeronautics and Space Harlan Watson Administration Department of State Margaret S. Leinen,Vice Chair National Science Foundation EXECUTIVE OFFICE AND OTHER LIAISONS James Andrews Kathie L. Olsen Department of Defense Office of Science and Technology Policy Co-Chair, Committee on Environment and Mary Glackin Natural Resources National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration David Conover Department of Energy Charles (Chip) Groat Director, Climate Change Technology Program U.S. Geological Survey Philip Cooney William Hohenstein Council on Environmental Quality Department of Agriculture David Halpern Linda Lawson Office of Science and Technology Policy Department of Transportation Margaret R. McCalla Melinda Moore Office of the Federal Coordinator Department of Health and Human Services for Meteorology Patrick Neale Erin Wuchte Smithsonian Institution Office of Management and Budget This document was prepared in compliance with Section 515 of the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 2001 (Public Law 106-554) and information quality guidelines issued by the Department of Commerce and NOAA pursuant to Section 515 (<http://www.noaanews.noaa.gov/stories/iq.htm>). For purposes of compliance with Section 515, this climate change science research program is an “interpreted product,” as that term is used in NOAA guidelines. -

Monbiot.Com » Faced with This Crisis 08/02/13 11:14

Monbiot.com » Faced With This Crisis 08/02/13 11:14 Monbiot.com Tell people something they know already and they will thank you for it. Tell them something new and they will hate you for it. Faced With This Crisis Posted July 12, 2005 The G8 leaders refuse to accept that anything difficult needs to be done about climate change By George Monbiot. Published in the Guardian, 12th July 2005. One day we will look back on the effort to deny the effects of climate change as we now look back on the work of Trofim Lysenko. Lysenko was a Soviet agronomist who insisted that the entire canon of genetics was wrong. There was no limit to an organism’s ability to adapt to changing environments. If cultivated correctly, crops could do anything the Soviet leadership wanted them to do. Wheat, for example, if grown in the right conditions, could be made to produce rye. Because he was able to mobilise enthusiasm among the peasants for collectivisation, and could present Stalin with a Soviet scientific programme, Lysenko’s hogwash became state policy. He was made director of the Institute of Genetics and president of the Lenin Academy of Agricultural Sciences. He used his position to outlaw conventional genetics, strip its practititioners of their positions and have some of them arrested and even killed. Lysenkoism, which governed state science from the late 1930s until the early 1960s, helped to wreck Soviet agriculture. No one is yet being sent to the Guantanamo gulag for producing the wrong results. But the denial of climate science in the United States bears some of the marks of Lysenkoism. -

Case 4:06-Cv-07062-SBA Document 32 Filed 02/08/2007 Page 1 of 36

Case 4:06-cv-07062-SBA Document 32 Filed 02/08/2007 Page 1 of 36 1 Deborah A. Sivas (Calif. Bar No. 135446) Holly D. Gordon (Calif. Bar. No. 226888) 2 Craig H. Segall (Certified Law Student) Samuel Woodworth (Certified Law Student) 3 Edwin Dietrich (Certified Law Student) STANFORD ENVIRONMENTAL LAW CLINIC 4 Crown Quadrangle 5 559 Nathan Abbott Way Stanford, California 94305 6 Telephone: (650) 723-0325 Facsimile: (650) 723-4426 7 E-mail: [email protected] 8 Attorneys for Amici Curiae U.S. SENATOR JOHN F. KERRY and 9 U.S. REPRESENTATIVE JAY INSLEE 10 11 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 12 FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 13 OAKLAND DIVISION 14 CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY,) Case No. C 06-7062 (SBA) 15 a non-profit corporation; GREENPEACE, ) Inc., a non-profit corporation; and FRIENDS ) 16 OF THE EARTH, a non-profit corporation, ) ) DECLARATION OF RICK S. PILTZ 17 Plaintiffs, ) IN SUPPORT OF MEMORANDUM OF 18 ) AMICI CURIAE JOHN F. KERRY AND v. ) JAY INSLEE 19 ) DR. WILLIAM BRENNAN, in his official ) 20 capacity as Acting Director of the U.S. ) Climate Change Science Program; U.S. ) 21 CLIMATE CHANGE SCIENCE ) PROGRAM; JOHN MARBURGER III, ) 22 in his official capacity as Director of the ) Office of Science and Technology Policy ) 23 and Chairman of the Federal Coordinating ) Technology; OFFICE OF SCIENCE AND ) 24 TECHNOLOGY POLICY; and FEDERAL ) 25 COORDINATING COUNCIL ON ) SCIENCE, ENGINEERING, AND ) 26 TECHNOLOGY, ) ) 27 Defendants. ) ) 28 DECLARATION OF RICK S. PILTZ IN SUPPORT OF MEMORANDUM OF AMICI CURIAE JOHN F. KERRY AND JAY INSLEE – Case No. -

M Truth Or Co2nsequences

TRUTH OR CO2NSEQUENCES ajor fossil fuel companies have known the truth This timeline highlights information, alleged in lawsuits M for nearly 50 years: their oil, gas, and coal products against fossil fuel companies, that comes from key create greenhouse gas pollution that warms the industry documents and other sources. It illustrates what planet and changes our climate. They’ve known for the industry knew, when they knew it, and what they decades that the consequences could be “catastrophic” didn’t do to prevent the impacts that are now imposing and that only a narrow window of time existed to take real costs on people and communities around the country. action before the damage might not be reversible. They While the early warnings from the industry’s own have nevertheless engaged in a coordinated, multi-front scientists and experts often acknowledged the effort to conceal and contradict their own knowledge of uncertainties in their projections, those uncertainties were these threats, discredit the growing body of publicly typically about the timing and magnitude of the climate available scientific evidence, and persistently create doubt change impacts – not about whether those impacts would in the minds of customers, consumers, regulators, the occur or whether the industry’s oil, gas, and coal were the media, journalists, policymakers, and the general public primary cause. On those latter points, as these documents about the reality and consequences of climate change. show, they were quite certain. DATE DOCUMENT TEXT “SOURCES OF AIR POLLUTION – “The petroleum industry supplies the fuel used by the automobile, TRANSPORTATION,” PRESENTATION and thus has a sincere interest in the solution to the problem of AT THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE ON pollution from automobile exhaust. -

In the Meantime, Thought You Might Enjoy the Ad That Provides a Bit More Truth in Advertising

Knutte, Caitlin From: Hendrickson, Cara Sent: Monday, March 21, 2016 8: 58 PM To: wendy Abrams Cc: Spillane, Ann M. Subject: Re: Exxon Document Thanks, Wendy. Best, Cara On Mar 21, 2016, at 6: 39 PM, wendy Abrams < wrote: I will forward this tomorrow. In the meantime, thought you might enjoy the ad that provides a bit more truth in advertising.. http:// youtu. be/ XhOezO s -Gs again, thank you for your time today. I cannot think of a more critical issue at a critical time; this could be a tipping point. Best, Wendy Begin forwarded message: From: " O' Neill, Christine M." < coneill2Alaw. pace. edu> Subject: Exxon Document Date: March 21, 2016 at 5: 45: 53 PM CDT To: Wendy Abrams < Hi Wendy, Bobby asked me to email the Exxon Mobil document that he sent to Eric Schneiderman. Unfortunately, it' s in my email archive folder and I can' t access it from home. Would it be okay if I sent to you tomorrow morning when I get to the office? Thanks, Christine Christine O' Neill Executive Assistant, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. Office: 914- 422- 4343 Cell: Knutte, Caitlin From: wendy abrams < Sent: Tuesday, March 22, 2016 9: 35 AM To: Spillane, Ann M.; Hendrickson, Cara Subject: Re: Madigan demands Peabody prove it has coal mine -closure money 1 Environment 1 thesouthern. com Attachments: ExxonMobilSchneidermanJan5FINAL. docx From Robert Kennedy. Jr. On Mar 22, 2016, at 8: 42 AM, Spillane, Ann M. < aspillane,ci atg. state. il. us> wrote: Thank you! And thank you for all of your time yesterday - that was really a helpful meeting. -

Smoke, Mirrors & Hot

Smoke, Mirrors & Hot Air How ExxonMobil Uses Big Tobacco’s Tactics to Manufacture Uncertainty on Climate Science Union of Concerned Scientists January 2007 © 2007 Union of Concerned Scientists All rights reserved The Union of Concerned Scientists is the leading science-based nonprofit working for a healthy environment and a safer world. UCS combines independent scientific research and citizen action to develop innovative, practical solutions and secure responsible changes in government policy, corporate practices, and consumer choices. Union of Concerned Scientists Two Brattle Square Cambridge, MA 02238-9105 Phone: 617-547-5552 Fax: 617-864-9405 Email: [email protected] Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 Background: The Facts about ExxonMobil 4 The Origins of a Strategy 6 ExxonMobil’s Disinformation Campaign 9 Putting the Brakes on ExxonMobil’s Disinformation Campaign 25 Appendices A. The Scientific Consensus on Global Warming 29 B. Groups and Individuals Associated with ExxonMobil’s Disinformation Campaign 31 C. Key Internal Documents 37 • 1998 "Global Climate Science Team" memo 38 • APCO memo to Philip Morris regarding the creation of TASCC 44 • Dobriansky talking points 49 • Randy Randol's February 6, 2001, fax to the Bush team calling for Watson's dismissal 51 • Sample mark up of Draft Strategic Plan for the Climate Change Science Program by Philip Cooney 56 • Email from Mryon Ebell, Competitive Enterprise Institute, to Phil Cooney 57 Endnotes 58 Acknowledgments Seth Shulman was the lead investigator and primary author of this report. Kate Abend and Alden Meyer contributed the final chapter. Kate Abend, Brenda Ekwurzel, Monica La, Katherine Moxhet, Suzanne Shaw, and Anita Spiess assisted with research, fact checking, and editing. -

The Politics and Culture of Climate Change: US Actors and Global Implications

Chapter 6 The Politics and Culture of Climate Change: US Actors and Global Implications Charles Waugh Abstract Despite the scientific consensus on global warming, many people in the USA,—both ordinary citizens and elected leaders alike—remain skeptical of the need to act, and in fact remain skeptical of the idea that humans are contributing to global warming at all. Thus, environmental justice arguments based on United States carbon emissions and the disproportionate impact of rising temperatures and rising sea levels on tropical developing nations such as Vietnam frequently fall on deaf ears. This chapter explores the political and cultural construction of this deafness, seeking a better understanding of how and why so many Americans refuse to act to address global warming. The two main sources of this deafness that this chapter address are (1) the politics of carbon-intensive energy producers such as the coal and oil industries, demonstrating the ways in which those industries have distorted the debate over global warming, have found eager allies in political candidates willing to accept large campaign contributions, and—with the help of other industries such as automobile manufacturing and home construction—have encouraged the second main source of denial: (2) a culture of aggrandized individualism that places greater value on personal identity construction than on the national and global common good. Once these sources are established, the chapter recommends strategies for using narrative to overcome cultural and political resistance to climate change miti- gation that may be effective not only in the United States, but in Vietnam as well. Keywords Climate change • Culture • Individualism • Narrative Since the election of Barack Obama in the United States, much has been made by the American news media of the new green economy, with the president himself calling for an investment in renewable energy and climate change mitigation strategies that he believes will have the twofold effect of resuscitating the American C. -

Creates a Legal Pleading

EXHIBIT A Truth or CO2nsequences AJOR FOSSIL FUEL COMPANIES have known the This timeline highlights information, alleged in the Mtruth for nearly 50 years: their oil, gas, and coal Complaints filed by San Mateo County, Marin County, and products create greenhouse gas pollution that warms Imperial Beach, that comes from key industry documents the planet and changes our climate. They’ve known for and other sources. It illustrates what the industry knew, decades that the consequences could be catastrophic and when they knew it, and what they didn’t do to prevent the that only a narrow window of time existed to take action impacts that are now imposing real costs on people and before the damage might not be reversible. They have communities around the country. While the early warnings nevertheless engaged in a coordinated, multi-front effort from the industry’s own scientists and experts often to conceal and contradict their own knowledge of these acknowledged the uncertainties in their projections, those threats, discredit the growing body of publicly available uncertainties were typically about the timing and magnitude scientific evidence, and persistently create doubt in the of the climate change impacts – not about whether those minds of customers, consumers, regulators, the media, impacts would occur or whether the industry’s oil, gas, journalists, teachers, and the general public about the and coal were the primary cause. On those latter points, reality and consequences of climate change. as these documents show, they were quite certain. DATE DOCUMENT TEXT President Lyndon Johnson’s Science Advisory Committee finds that “[P]ollutants have altered on a global scale the carbon “RESTORING THE QUALITY OF dioxide content of the air” and “[M]an is unwittingly conducting OUR ENVIRONMENT,” REPORT OF a vast geophysical experiment” by burning fossil fuels that are NOV. -

Primary Documents

An Exercise in Scientific Integrity: Uncovering the Truth Using Primary Documents Investigations into alleged encroachments on scientific integrity typically begin either with leaked documents or information provided by whistleblowers (employees who report misconduct such as fraud, safety violations, or corruption). The next phase of investigation, depending on the issue, involves writing letters to and conducting interviews with the relevant people, and obtaining all the documentation available. Frequently, requests for additional agency documentation are filed under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). This process can take anywhere from months to years to complete, and court orders are sometimes needed to force an agency to release information. Media coverage can also be a vital tool in pressuring reticent agencies to acknowledge misconduct. The following real-life examples are meant to recreate the experience of a researcher looking into federal scientific integrity issues. Excerpts from primary documents are provided along with some background facts, allowing you to draw your own conclusions. For each example, write a short essay explaining the issue at hand, what you are able to surmise from the information provided to you, and whether or not scientific integrity was compromised. Your argument should be reasonable and supported with evidence. I. Edits to Climate Documents In the spring of 2005, Rick Piltz, a senior associate with the Climate Change Science Program (CCSP, a federal agency responsible for integrating the climate change research of 13 federal agencies), announced his resignation. Among his reasons, Piltz alleged that Philip Cooney, then chief of staff of the White House Council on Environmental Quality, inappropriately edited CCSP scientific documents.