Volume 61, Part I 2013 Agricultural History Review Volume 61 Part I 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 3 Formal Resolution

Appendix 3 Formal Resolution Council Taxes for the year ending 31 March 2022 1. The recommended council tax requirement for the Borough Council’s own purposes (and excluding Parish precepts) is £8,756,147 2. It be noted that the Section 151 Officer (Executive Director of Corporate Services) on 08 January 2021 calculated the Council Tax Base for 2021/22 for the whole Borough area as 66,627.2 (Item T in the formula in Section 31B of the Local Government Finance Act 1992) and, for dwellings in those parts of its area to which a Parish precept relates as per Appendix 2 (column 3). 3. That the following amounts be now calculated by the Council for the year 2021/22 in accordance with Sections 31 to 36 of the Local Government Finance Act 1992 and subsequent regulations: (a) £142,474,348.00 being the aggregate of the amounts which the Council estimates for the items set out in Section 31A(2) of the Act taking into account all precepts issued to it by Parish Councils. (b) £132,169,900.00 being the aggregate of the amounts which the Council estimates for the items set out in Section 31A(3) of the Act. (c) £10,304,448.00 being the amount by which the aggregate at 3(a) above exceeds the aggregate at 3(b) above, calculated by the Council in accordance with Section 31A(4) of the Act as its council tax requirement for the year. (Item R in the formula in Section 31B of the Act). (d) £154.66 being the amount at 3(c) above (Item R), all divided by Item T (2 above), calculated by the Council, in accordance with Section 31B(1) of the Act, as the basic amount of its Council Tax for the year (including Parish precepts). -

Landowner Deposits Register

Register of Landowner Deposits under Highways Act 1980 and Commons Act 2006 The first part of this register contains entries for all CA16 combined deposits received since 1st October 2013, and these all have scanned copies of the deposits attached. The second part of the register lists entries for deposits made before 1st October 2013, all made under section 31(6) of the Highways Act 1980. There are a large number of these, and the only details given here currently are the name of the land, the parish and the date of the deposit. We will be adding fuller details and scanned documents to these entries over time. List of deposits made - last update 12 January 2017 CA16 Combined Deposits Deposit Reference: 44 - Land at Froyle (The Mrs Bootle-Wilbrahams Will Trust) Link to Documents: http://documents.hants.gov.uk/countryside/Deposit44-Bootle-WilbrahamsTrustLand-Froyle-Scan.pdf Details of Depositor Details of Land Crispin Mahony of Savills on behalf of The Parish: Froyle Mrs Bootle-WilbrahamWill Trust, c/o Savills (UK) Froyle Jewry Chambers,44 Jewry Street, Winchester Alton Hampshire Hampshire SO23 8RW GU34 4DD Date of Statement: 14/11/2016 Grid Reference: 733.416 Deposit Reference: 98 - Tower Hill, Dummer Link to Documents: http://documents.hants.gov.uk/rightsofway/Deposit98-LandatTowerHill-Dummer-Scan.pdf Details of Depositor Details of Land Jamie Adams & Madeline Hutton Parish: Dummer 65 Elm Bank Gardens, Up Street Barnes, Dummer London Basingstoke SW13 0NX RG25 2AL Date of Statement: 27/08/2014 Grid Reference: 583. 458 Deposit Reference: -

The Distribution of the Romano-British Population in The

PAPERS AND PROCEEDINGS 119 THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE ROMANO - BRITISH POPULATION IN THE BASINGSTOKE AREA. By SHIMON APPLEBAUM, BXITT., D.PHIL. HE district round Basingstoke offers itself as the subject for a study of Romano-British . population development and. Tdistribution because Basingstoke Museum contains a singu larly complete collection of finds made in this area over a long period of years, and preserved by Mr. G. W. Willis. A number of the finds made are recorded by him and J. R. Ellaway in the Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club (Vol. XV, 245 ff.). The known sites in the district were considerably multiplied by the field-work of S. E. Winbolt, who recorded them in the Proceedings of the same Society.1 I must express my indebtedness to Mr. G. W. Willis, F.S.A., Hon. Curator of Basingstoke Museum, for his courtesy and assist ance in affording access to the collection for the purposes of this study, which is part of a broader work on the Romano-British rural system.2 The area from which the bulk of the collection comes is limited on the north by the edge of the London Clay between Kingsclere and Odiham ; its east boundary is approximately that, of the east limit of the Eastern Hampshire High Chalk Region' southward to Alton. The south boundary crosses that region through Wilvelrod, Brown Candover and Micheldever, with outlying sites to the south at Micheldever Wood and Lanham Down (between Bighton and Wield). The western limit, equally arbitrary, falls along the line from Micheldever through Overton to Kingsclere. -

Mapledurwell & up Nately

Diary dates The Villager October October 2019 Volume 48 No 9 1 St Mary’s Holy Dusters, The community newsletter for Mapledurwell, Maple, 10am Up Nately, Newnham, Nately Scures & Greywell 6 Greywell Art Competition & Dear Residents Harvest Tea Party, Village I am seeking any information in relation to the below incidents, if you can assist please call me direct, as always all calls treated Hall, 4-5.30pm in strictest confidence. We have been experiencing an increase in burglary to outbuildings 11 Up Nately Coffee Morning, across the area, between midnight and 7 am on August 5th an outbuilding Eastrop Cottage, 10-12 was broken into at a property in Crown Lane, Newnham where a substantial amount of garden tools and equipment was stolen along with a blue Yamaha 16 Maple Tea Party, quad bike registration YJ07 YSW. On the same night two other premises were Crosswater Cottage, broken into at Herriard at 3.30 am. 3.30pm Between August 12th and 25th a further burglary to an outbuilding took place, this time at a property on the Greywell Road at Andwell when again a substantial amount of garden machinery etc. was stolen along with a black 17 Greywell Cafe, Village Hall, Polaris all-terrain vehicle registration BK65 GUE. 3-4pm Between September 9th and 12th a garage was broken into in Blackstocks Lane where two pedal cycles were stolen, also in Blackstocks Lane overnight of 17 Travels to Timbuktu, North September 24th 2019 a further garage was broken into a small 4x4 was stolen Warnborough Village Hall, which has since been recovered. -

Bicentenary Programme Celebrating the Life and Legacy of James Watt

Bicentenary programme celebrating the life and legacy of James Watt 2019 marks the 200th anniversary of the death of the steam engineer James Watt (1736-1819), one of the most important historic figures connected with Birmingham and the Midlands. Born in Greenock in Scotland in 1736, Watt moved to Birmingham in 1774 to enter into a partnership with the metalware manufacturer Matthew Boulton. The Boulton & Watt steam engine was to become, quite literally, one of the drivers of the Industrial Revolution in Britain and around the world. Although best known for his steam engine work, Watt was a man of many other talents. At the start of his career he worked as both a mathematical instrument maker and a civil engineer. In 1780 he invented the first reliable document copier. He was also a talented chemist who was jointly responsible for proving that water is a compound rather than an element. He was a member of the famous Lunar Portrait of James Watt by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1812 Society of Birmingham, along with other Photo by Birmingham Museums Trust leading thinkers such as Matthew Boulton, Erasmus Darwin, Joseph Priestley and The 2019 James Watt Bicentenary Josiah Wedgwood. commemorative programme is The Boulton & Watt steam engine business coordinated by the Lunar Society. was highly successful and Watt became a We are delighted to be able to offer wealthy man. In 1790 he built a new house, a wide-ranging programme of events Heathfield Hall in Handsworth (demolished and activities in partnership with a in 1927). host of other Birmingham organisations. Following his retirement in 1800 he continued to develop new inventions For more information about the in his workshop at Heathfield. -

James Watt 2019 National Lottery Heritage Fund Evaluation CONTENTS

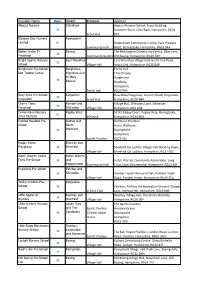

PMP Consultants Limited Phone: 0121 585 6340 E-mail: [email protected] Business Development Manager Web : www.pmpconsultants.co.uk James Watt 2019 National Lottery Heritage Fund Evaluation CONTENTS Page Executive Summary 4 1. Chapter One Introduction 9 Project staffing 12 Project Management and Delivery 12 2. Chapter Two - Anticipated Outputs and Outcomes The Evaluation Process 25 Anticipated Outputs 27 Anticipated Outcomes 28 Methodology 30 3. Chapter Three - Evaluation Outcomes for Heritage 36 Heritage will be better interpreted and explained 38 Heritage will be in better condition 46 Heritage will be better identified and recorded 48 4. Chapter Four - Outcomes for People People will have learnt about heritage 54 People will have developed skills 70 People will have changed attitudes and behaviours 74 People will have had an enjoyable experience 78 People will have volunteered time 82 5. Chapter Five - Outcomes for Communities More people will have engaged with heritage 88 Local economies will have been boosted 92 Communities will be a better place to live, work or visit 94 6. Chapter Six - Review - Learning and Legacies Project Learning 99 Critical Success Factors 100 Recommendations 102 2 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Purpose of this document What happened? This document is the final report of an in-depth evaluation study which To commemorate, celebrate and explore the life of James Watt and his global has been conducted throughout the duration of the James Watt 2019 legacy, over 100 different activities and events have taken place across Birmingham, project. The objectives of this report are to carry out an independent all part of The James Watt 2019 programme. -

Provider Name WARD Premises Address Scout Hut Abacus Nursery

Provider Name Open WARD Premises Address Abacus Nursery Chineham Abacus Nursery School, Scout Building, 38 Hanmore Road, Chineham, Hampshire, RG24 Scout Hut 8PJ Blossom Day Nursery Rooksdown Limited 51 Rooksdown Community Centre, Park Prewett Community Hall Road, Basingstoke, Hampshire, RG24 9XA Bolton Under 5's Basing The Beddington Community Centre, Riley Lane, 38 Preschool Community BuildingOld Basing, Hampshire, RG24 7DH Bright Sparks Nursery East Woodhay East Woodhay Village Hall, Heath End Road, 38 School Village Hall Heath End, Hampshire, RG20 0AP Burghclere Pre-School Burghclere, Portal Hall and Toddler Group Highclere and Church Lane St Mary Burghclere 38 Bourne Newbury Hampshire Portal Hall RG20 9HX Busy Bees Pre-School - Kingsclere Busy Bees Playgroup, Strokins Road, Kingsclere, 38 Kingsclere Scout Hut Hampshire, RG20 5RH Cherry Trees Pamber and Village Hall, Whistlers Lane, Silchester, 38 Preschool Silchester Village Hall Hampshire, RG7 2NE Cornerstone Nursery Popley West 52-53 Abbey Court, Popley Way, Basingstoke, 51 (Miss Muffett) BD lease Hampshire, RG24 9DX Cuckoo Meadow Pre- Oakley and Rathbone Pavillion school North North Waltham 38 Waltham Basingstoke Hampshire Sports Pavilion RG25 2BL Happy Faces Bramley and Playgroup 38 Sherfield Sherfield On Loddon Village Hall, Reading Road, Village Hall Sherfield-On-Loddon, Hampshire, RG27 0EZ Hatch Warren Under Hatch Warren Fives Pre-School 38 and Hatch Warren Community Association, Long Beggarwood Community Hall Cross Lane, Basingstoke, Hampshire, RG22 4XF Impstone Pre-school -

Parish and Path No

Definitive Statements for the Parish of: Mapledurwell and Up Nately ................................................................................................ 1 Marchwood .......................................................................................................................... 6 Martin................................................................................................................................... 9 Mattingley .......................................................................................................................... 14 Medstead ........................................................................................................................... 19 Melchet Park and Plaitford ................................................................................................. 24 Micheldever ....................................................................................................................... 26 Michelmersh and Timsbury ................................................................................................ 32 Milford-on-Sea ................................................................................................................... 35 Minstead ............................................................................................................................ 40 Monk Sherborne ................................................................................................................ 42 Monxton ............................................................................................................................ -

Appendix 11 Basingstoke and Deane Borough Council Parish

Appendix 11 Basingstoke and Deane Borough Council Parish Requirements 2014/15 Council Council Tax Element Tax for Parish Purposes Parish/Area Precept Base (*) at Band D (**) £ £ (1) (2) (3) (4) Ashford Hill with Headley 19,000.00 599.3 31.70 Ashmansworth 3,000.00 106.4 28.20 Baughurst 38,500.00 1,015.3 37.92 Bramley 65,000.00 1,590.8 40.86 Burghclere 9,600.00 554.0 17.33 Candovers 3,000.00 101.2 29.64 Chineham 36,800.00 3,072.7 11.98 Cliddesden 5,850.00 231.1 25.31 Dummer 6,500.00 219.5 29.61 East Woodhay 25,165.00 1,301.7 19.33 Ecchinswell, Sydmonton and Bishops Green 11,299.00 421.4 26.81 Ellisfield 5,521.00 145.2 38.02 Hannington 3,312.00 184.6 17.94 Highclere 13,466.00 741.7 18.16 Hurstbourne Priors 7,000.00 177.9 39.35 Kingsclere 40,735.00 1,284.2 31.72 Laverstoke and Freefolk 10,000.00 166.7 59.99 Mapledurwell and Up Nately 6,562.00 276.6 23.72 Monk Sherborne 9,450.00 179.8 52.56 Mortimer West End 7,400.00 180.2 41.07 Newnham 6,122.00 237.1 25.82 Newtown 3,500.00 131.3 26.66 North Waltham 10,100.00 384.2 26.29 Oakley and Deane 76,695.00 2,240.9 34.23 Old Basing and Lychpit 129,574.00 3,079.0 42.08 Overton 66,570.00 1,707.9 38.98 Pamber 25,500.00 1,160.3 21.98 Preston Candover and Nutley 7,000.00 239.2 29.26 Rooksdown 19,600.00 1,358.8 14.42 Sherborne St John 22,700.00 521.5 43.53 Sherfield-on-Loddon 75,000.00 1,514.3 49.53 Silchester 14,821.00 417.7 35.48 St Mary Bourne 19,572.00 578.9 33.81 Stratfield Saye 2,750.00 136.9 20.09 Tadley 186,466.00 4,004.5 46.56 Upton Grey 14,000.00 343.5 40.76 Whitchurch 75,000.00 1,846.4 40.62 Wootton -

Parish and Settlement Groupsm

Q1. Which village, town or part of a town do you consider as your "local area"? East of Basingstoke (generic) Where more than one of the following is mentioned: Old Basing Bramley Chineham Lychpit Mapledurwell Nately Scures Newnham Sherfield on loddon Bramley Chineham Sherfield park Taylor’s farm Lychpit Newnham Old Basing Sherfield on loddon Eastern parishes Mapledurwell Nately Scures Scures hill Up Nately Basingstoke town Basingstoke North East Marnel park Norden Oakridge Popley South View Basingstoke North West Rooksdown Winklebury Basingstoke Central Berg estate Brookvale Cranbourne Down Grange Eastrop Fairfields Kings Furlong Riverdene South Ham Basingstoke West Buckskin Clarke estate Kempshott Manydown Pack Lane Roman road Worting Basingstoke South Black Dam Brighton Hill Viables Basingstoke South West Beggarwood Hatch Warren Oakley and Deane Oakley Harrow Way Deane Newfound Burghclere Highclere Kingsclere Woolton Hill Northern western parishes Ashford Hill and Headley Ashmansworth Ball Hill Bishops Green Burghclere East Woodhay Ecchinswell Headley Hannington Penwood North eastern parishes (exc Bramley/Sherfield on Loddon) Hartley Wespall Stratfield Saye Stratfield Turgis Ellisfield South east parishes (excl. Ellisfield) Axford, Nutley, Preston Candover Bradley Cliddesden Dummer Fairleigh wallop Herriard Nutley Preston Candover Tunworth Upton Grey Weston Patrick Tadley Northern parishes (exc Tadley) Baughurst Silchester Charter Alley Little London Newtown Pamber End Pamber Green Pamber Heath Ramsdell Wolverton common North of Basingstoke Sherborne St John Monk Sherborne Wootton St Lawrence Overton Southern parishes North Waltham Steventon Whitchurch South West parishes Hurstborne Priors Laverstoke St Mary Bourne Stoke Other Other Basingstoke & Deane Andover Burghfield Hook Eversley Fleet Micheldever Newbury Odiham Winchester . -

RELIGIOUS HISTORY Parochial Organisation Early References to the Parochial Organisation for Nately Scures Are Obscure. in the 12

RELIGIOUS HISTORY Parochial Organisation Early references to the parochial organisation for Nately Scures are obscure. In the 12th century the first identifiable holder of ecclesiastical office in the parish was simply denoted as a cleric.1 From the 14th century Nately Scures is known to have been served by a rector. From the 17th century onwards the rector of Nately Scures was frequently assisted by a curate. Many rectors of Nately Scures combined their living with other ecclesiastical offices. During the 1920s the church’s financial position was becoming increasingly untenable and a possible amalgamation with several neighbouring parishes was mooted. Despite opposition to the proposal, in 1935 Nately Scures lost its independence.2 Although this lasted 21 years, further reorganisations or amalgamations occurred in 1956 and culminated in June 2008 in the formation of the North Downs benefice, with its eight parishes and 12 churches. Glebe and Tithes The size of the glebe is not known but in 1662 the rector, the Revd John Palmer, cultivated 1 ½ a. of wheat and 1 ¼ a. of oats on it.3 In the early 19th century curates of Nately Scures were permitted to reside on the glebe.4 It was probably not the most extravagant of settings as Richard Carleton cited the unfitness of the glebe house as the reason for his non residency in the parish in 18365, 18386 and 1845.7 The reason for this may have been the fact that Nately Scures is a relatively small parish with small population. In 1841 £128 was due to the church in rent from the parish.8 The Religious Census of 1851 recorded that net worth of the tithes was £170 and the glebe was worth £15. -

Mapledurwell & up Nately

The community newsletter for Mapledurwell, Up Nately, The Villager Newnham, Nately Scures & December 2020/January 2021 Volume 49 No 11 Greywell The Villager would like to thank all contributors and distributors and wish you all a happy festive season CHRISTMAS SERVICES IN THE FIVE VILLLAGES Please join us for any of these special Christmas services Christmas Eve 4.30pm Up Nately Outdoor Crib Service 11.30pm Nately Scures/ Newnham Midnight Communion (Booking Required and venue will be confirmed once we have an idea of numbers.) Christmas Day 9.30am Up Nately Christmas Day Communion 9.30m Mapledurwell Christmas Day Family Service 10.45am Newnham Christmas Day Communion 10.45am Greywell Christmas Day Family Service (Booking Required for all Services) Wishing you all a very Happy Christmas and a peaceful New Year CONFUSED BY YOUR COMPUTER? TROUBLED BY YOUR TELEVISION SET? GREYWELL HILL ESTATE RUNNING LOGS SLOW VIRUS SPYWARE Seasoned hardwood logs (oak, ash, beech, birch et al) NO BLUE INTERNET SCREEN Cut when dry in the summer and stored in a barn Delivered in wire cage (to be returned) approximate capacity On site visits include Prices from 1 cubic metre (35 cu ft) £125 Desktop, Laptop, Ipad, Printers £45 on site Covers the first Repair, Service & Support Hour or Virus / Spyware removal Problems with Email, Printer, Internet access (fixed) Very full trailer approximate capacity 3 cu m (105 cu ft) £250 Regular maintenance keeps your computer clean and fast Tel: Office 01256 703565 or Nigel 07973 715361 Prices from On site visits for £45 + Parts TV, Audio & Video Repair 1st Hour Villager Contact Details TV Tuning and Setup Prices from Supply and Install Freeview receivers £35 Editor: Stephanie Webb 07717 403610 - [email protected]; Advice and Support.