Chapter Five South Australia and Federation Professor Peter Howell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Release

MEDIA RELEASE 7 February 2017 Premier awards Tennyson Medal at SACE Merit Ceremony The Premier of South Australia, the Hon. Jay Weatherill MP, awarded the prestigious Tennyson Medal for excellence in English Studies to 2016 Year 12 graduate, Ashleigh Jones at the SACE Merit Ceremony at Government House today. The ceremony, in its twenty-ninth year, saw 996 students awarded with 1302 subject merits for outstanding achievement in SACE Stage 2 subjects. Subject merits are awarded to students who gain an overall subject grade of A+ and demonstrate exceptional achievement in that subject. As part of the Merit Ceremony, His Excellency the Hon. Hieu Van Le AC, the Governor of South Australia, presented the following awards: Governor of South Australia Commendation for outstanding overall achievement in the SACE (twenty-five recipients in 2016) Governor of South Australia Commendation — Aboriginal Student SACE Award for the Aboriginal student with the highest overall achievement in the SACE Governor of South Australia Commendation – Excellence in Modified SACE Award for the student with an identified intellectual disability who demonstrates outstanding achievement exclusively through SACE modified subjects. The Tennyson Medal dates back to 1901 when the former Governor of South Australia, Lord Tennyson, established the Tennyson Medal to encourage the study of English literature. The long list of recipients includes the late John Bannon AO, 39th Premier of South Australia, who was awarded the medal in 1961. For her Year 12 English Studies, Ashleigh studied works by Henrik Ibsen (A Doll’s House), Zhang Yimou who directed Raise the Red Lantern, and Tennessee Williams (The Glass Menagerie). -

Abortion, Homosexuality and the Slippery Slope: Legislating ‘Moral’ Behaviour in South Australia

Abortion, Homosexuality and the Slippery Slope: Legislating ‘Moral’ Behaviour in South Australia Clare Parker BMusSt, BA(Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Discipline of History, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Adelaide. August 2013 ii Contents Contents ii Abstract iv Declaration vi Acknowledgements vii List of Abbreviations ix List of Figures x A Note on Terms xi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: ‘The Practice of Sound Morality’ 21 Policing Abortion and Homosexuality 24 Public Conversation 36 The Wowser State 44 Chapter 2: A Path to Abortion Law Reform 56 The 1930s: Doctors, Court Cases and Activism 57 World War II 65 The Effects of Thalidomide 70 Reform in Britain: A Seven Month Catalyst for South Australia 79 Chapter 3: The Abortion Debates 87 The Medical Profession 90 The Churches 94 Activism 102 Public Opinion and the Media 112 The Parliamentary Debates 118 Voting Patterns 129 iii Chapter 4: A Path to Homosexual Law Reform 139 Professional Publications and Prohibited Literature 140 Homosexual Visibility in Australia 150 The Death of Dr Duncan 160 Chapter 5: The Homosexuality Debates 166 Activism 167 The Churches and the Medical Profession 179 The Media and Public Opinion 185 The Parliamentary Debates 190 1973 to 1975 206 Conclusion 211 Moral Law Reform and the Public Interest 211 Progressive Reform in South Australia 220 The Slippery Slope 230 Bibliography 232 iv Abstract This thesis examines the circumstances that permitted South Australia’s pioneering legalisation of abortion and male homosexual acts in 1969 and 1972. It asks how and why, at that time in South Australian history, the state’s parliament was willing and able to relax controls over behaviours that were traditionally considered immoral. -

Justice Richard O'connor and Federation Richard Edward O

1 By Patrick O’Sullivan Justice Richard O’Connor and Federation Richard Edward O’Connor was born 4 August 1854 in Glebe, New South Wales, to Richard O’Connor and Mary-Anne O’Connor, née Harnett (Rutledge 1988). The third son in the family (Rutledge 1988) to a highly accomplished father, Australian-born in a young country of – particularly Irish – immigrants, a country struggling to forge itself an identity, he felt driven to achieve. Contemporaries noted his personable nature and disarming geniality (Rutledge 1988) like his lifelong friend Edmund Barton and, again like Barton, O’Connor was to go on to be a key player in the Federation of the Australian colonies, particularly the drafting of the Constitution and the establishment of the High Court of Australia. Richard O’Connor Snr, his father, was a devout Roman Catholic who contributed greatly to the growth of Church and public facilities in Australia, principally in the Sydney area (Jeckeln 1974). Educated, cultured, and trained in multiple instruments (Jeckeln 1974), O’Connor placed great emphasis on learning in a young man’s life and this is reflected in the years his son spent attaining a rounded and varied education; under Catholic instruction at St Mary’s College, Lyndhurst for six years, before completing his higher education at the non- denominational Sydney Grammar School in 1867 where young Richard O’Connor met and befriended Edmund Barton (Rutledge 1988). He went on to study at the University of Sydney, attaining a Bachelor of Arts in 1871 and Master of Arts in 1873, residing at St John’s College (of which his father was a founding fellow) during this period. -

Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention

The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention* Geoffrey Bolton dmund Barton first entered my life at the Port Hotel, Derby on the evening of Saturday, E13 September 1952. As a very young postgraduate I was spending three months in the Kimberley district of Western Australia researching the history of the pastoral industry. Being at a loose end that evening I went to the bar to see if I could find some old-timer with an interesting store of yarns. I soon found my old-timer. He was a leathery, weather-beaten station cook, seventy-three years of age; Russel Ward would have been proud of him. I sipped my beer, and he drained his creme-de-menthe from five-ounce glasses, and presently he said: ‘Do you know what was the greatest moment of my life?’ ‘No’, I said, ‘but I’d like to hear’; I expected to hear some epic of droving, or possibly an anecdote of Gallipoli or the Somme. But he answered: ‘When I was eighteen years old I was kitchen-boy at Petty’s Hotel in Sydney when the federal convention was on. And every evening Edmund Barton would bring some of the delegates around to have dinner and talk about things. I seen them all: Deakin, Reid, Forrest, I seen them all. But the prince of them all was Edmund Barton.’ It struck me then as remarkable that such an archetypal bushie, should be so admiring of an essentially urban, middle-class lawyer such as Barton. -

The Making of White Australia

The making of White Australia: Ruling class agendas, 1876-1888 Philip Gavin Griffiths A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University December 2006 I declare that the material contained in this thesis is entirely my own work, except where due and accurate acknowledgement of another source has been made. Philip Gavin Griffiths Page v Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations xiii Abstract xv Chapter 1 Introduction 1 A review of the literature 4 A ruling class policy? 27 Methodology 35 Summary of thesis argument 41 Organisation of the thesis 47 A note on words and comparisons 50 Chapter 2 Class analysis and colonial Australia 53 Marxism and class analysis 54 An Australian ruling class? 61 Challenges to Marxism 76 A Marxist theory of racism 87 Chapter 3 Chinese people as a strategic threat 97 Gold as a lever for colonisation 105 The Queensland anti-Chinese laws of 1876-77 110 The ‘dangers’ of a relatively unsettled colonial settler state 126 The Queensland ruling class galvanised behind restrictive legislation 131 Conclusion 135 Page vi Chapter 4 The spectre of slavery, or, who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 137 The political economy of anti-slavery 142 Indentured labour: The new slavery? 149 The controversy over Pacific Islander ‘slavery’ 152 A racially-divided working class: The real spectre of slavery 166 Chinese people as carriers of slavery 171 The ruling class dilemma: Who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 176 A divided continent? Parkes proposes to unite the south 183 Conclusion -

Sixteen Years of Labor Government in South Australia, 2002-2018

AUSTRALASIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW Parliament in the Periphery: Sixteen Years of Labor Government in South Australia, 2002-2018* Mark Dean Research Associate, Australian Industrial Transformation Institute, Flinders University of South Australia * Double-blind reviewed article. Abstract This article examines the sixteen years of Labor government in South Australia from 2002 to 2018. With reference to industry policy and strategy in the context of deindustrialisation, it analyses the impact and implications of policy choices made under Premiers Mike Rann and Jay Weatherill in attempts to progress South Australia beyond its growing status as a ‘rustbelt state’. Previous research has shown how, despite half of Labor’s term in office as a minority government and Rann’s apparent disregard for the Parliament, the executive’s ‘third way’ brand of policymaking was a powerful force in shaping the State’s development. This article approaches this contention from a new perspective to suggest that although this approach produced innovative policy outcomes, these were a vehicle for neo-liberal transformations to the State’s institutions. In strategically avoiding much legislative scrutiny, the Rann and Weatherill governments’ brand of policymaking was arguably unable to produce a coordinated response to South Australia’s deindustrialisation in a State historically shaped by more interventionist government and a clear role for the legislature. In undermining public services and hollowing out policy, the Rann and Wethearill governments reflected the path dependency of responses to earlier neo-liberal reforms, further entrenching neo-liberal responses to social and economic crisis and aiding a smooth transition to Liberal government in 2018. INTRODUCTION For sixteen years, from March 2002 to March 2018, South Australia was governed by the Labor Party. -

Introduction to Volume 1 the Senators, the Senate and Australia, 1901–1929 by Harry Evans, Clerk of the Senate 1988–2009

Introduction to volume 1 The Senators, the Senate and Australia, 1901–1929 By Harry Evans, Clerk of the Senate 1988–2009 Biography may or may not be the key to history, but the biographies of those who served in institutions of government can throw great light on the workings of those institutions. These biographies of Australia’s senators are offered not only because they deal with interesting people, but because they inform an assessment of the Senate as an institution. They also provide insights into the history and identity of Australia. This first volume contains the biographies of senators who completed their service in the Senate in the period 1901 to 1929. This cut-off point involves some inconveniences, one being that it excludes senators who served in that period but who completed their service later. One such senator, George Pearce of Western Australia, was prominent and influential in the period covered but continued to be prominent and influential afterwards, and he is conspicuous by his absence from this volume. A cut-off has to be set, however, and the one chosen has considerable countervailing advantages. The period selected includes the formative years of the Senate, with the addition of a period of its operation as a going concern. The historian would readily see it as a rational first era to select. The historian would also see the era selected as falling naturally into three sub-eras, approximately corresponding to the first three decades of the twentieth century. The first of those decades would probably be called by our historian, in search of a neatly summarising title, The Founders’ Senate, 1901–1910. -

Who's That with Abrahams

barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008/09 Who’s that with Abrahams KC? Rediscovering Rhetoric Justice Richard O’Connor rediscovered Bullfry in Shanghai | CONTENTS | 2 President’s column 6 Editor’s note 7 Letters to the editor 8 Opinion Access to court information The costs circus 12 Recent developments 24 Features 75 Legal history The Hon Justice Foster The criminal jurisdiction of the Federal The Kyeema air disaster The Hon Justice Macfarlan Court NSW Law Almanacs online The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina The Hon Justice Ward Saving St James Church 40 Addresses His Honour Judge Michael King SC Justice Richard Edward O’Connor Rediscovering Rhetoric 104 Personalia The current state of the profession His Honour Judge Storkey VC 106 Obituaries Refl ections on the Federal Court 90 Crossword by Rapunzel Matthew Bracks 55 Practice 91 Retirements 107 Book reviews The Keble Advocacy Course 95 Appointments 113 Muse Before the duty judge in Equity Chief Justice French Calderbank offers The Hon Justice Nye Perram Bullfry in Shanghai Appearing in the Commercial List The Hon Justice Jagot 115 Bar sports barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008-09 Bar News Editorial Committee Cover the New South Wales Bar Andrew Bell SC (editor) Leonard Abrahams KC and Clark Gable. Association. Keith Chapple SC Photo: Courtesy of Anthony Abrahams. Contributions are welcome and Gregory Nell SC should be addressed to the editor, Design and production Arthur Moses SC Andrew Bell SC Jeremy Stoljar SC Weavers Design Group Eleventh Floor Chris O’Donnell www.weavers.com.au Wentworth Chambers Duncan Graham Carol Webster Advertising 180 Phillip Street, Richard Beasley To advertise in Bar News visit Sydney 2000. -

Annual Report 2004-2005

Annual Report 2004/2005 Governing partners Supported by Contents Report from the Chair of Trustees 4 Summary of Activities: “There is still much to be done” 6 Foundation Year in Review 10 Trustees’ Report 22 • Statement of Financial Performance 23 • Statement of Financial Position 24 • Statement of Cash Flows 25 • Notes to the Financial Statements 26 • Declaration by Trustees 35 • Independent Audit Report 36 Trustees, Board and Staff 38 Our supporters 40 The Annual Report Published March 2006 By the Don Dunstan Foundation Level 3, 10 Pulteney Street The University of Adelaide, SA 5005 http://www.dunstan.org.au ABN 71 448 549 600 Don Dunstan Foundation Annual Report 2004/2005 Page 2/40 Don Dunstan Foundation Values • Respect for fundamental human rights • Celebration of cultural and ethnic diversity • Freedom of individuals to control their lives • Just distribution of global wealth • Respect for indigenous people and protection of their rights • Democratic and inclusive forms of governance Strategic Directions • Facilitate a productive exchange between academic researchers and Government policy makers • Invigorate policy debate and responses • Consolidate and expand the Foundation’s links with the wider community • Support Chapter activities • Build and maintain the long-term viability of the Foundation Don Dunstan Foundation Annual Report 2004/2005 Page 3/40 REPORT FROM THE CHAIR The financial year 2004/2005 has been extremely productive with the Foundation continuing its drive to implement its Strategic Directions and Strategic Business Plan. The Foundation has provided an array of targeted events, pursued key projects of community benefit, enhanced its infrastructure and promoted its contribution to the wider South Australian Community. -

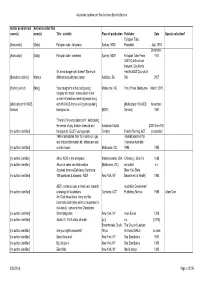

Books at 2016 05 05 for Website.Xlsx

Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives Book Collection Author or editor last Author or editor first name(s) name(s) Title : sub-title Place of publication Publisher Date Special collection? Fallopian Tube [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : fallopiana Sydney, NSW Pamphlet July, 1974 December, [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : madness Sydney, NSW Fallopian Tube Press 1974 GLBTIQ with cancer Network, Gay Men's It's a real bugger isn't it dear? Stories of Health (AIDS Council of [Beresford (editor)] Marcus different sexuality and cancer Adelaide, SA SA) 2007 [Hutton] (editor) [Marg] Your daughter's at the door [poetry] Melbourne, VIC Panic Press, Melbourne March, 1975 Inequity and hope : a discussion of the current information needs of people living [Multicultural HIV/AIDS with HIV/AIDS from non-English speaking [Multicultural HIV/AIDS November, Service] backgrounds [NSW] Service] 1997 "There's 2 in every classroom" : Addressing the needs of gay, lesbian, bisexual and Australian Capital [2001 from 100 [no author identified] transgender (GLBT) young people Territory Family Planning, ACT yr calendar] 1995 International Year for Tolerance : gay International Year for and lesbian information kit : milestones and Tolerance Australia [no author identified] current issues Melbourne, VIC 1995 1995 [no author identified] About AIDS in the workplace Massachusetts, USA Channing L Bete Co 1988 [no author identified] Abuse in same sex relationships [Melbourne, VIC] not stated n.d. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome : [New York State [no author identified] 100 questions & answers : AIDS New York, NY Department of Health] 1985 AIDS : a time to care, a time to act, towards Australian Government [no author identified] a strategy for Australians Canberra, ACT Publishing Service 1988 Adam Carr And God bless Uncle Harry and his roommate Jack (who we're not supposed to talk about) : cartoons from Christopher [no author identified] Street Magazine New York, NY Avon Books 1978 [no author identified] Apollo 75 : Pix & story, all male [s.l.] s.n. -

Votes for Women ©

1 VOTES FOR WOMEN © Condensed for the Women & Politics website by Dr Helen Jones from her book In her own name: a history of women in South Australia revised edition (Adelaide, Wakefield Press, 1994). On a hot December morning in 1894, a week before Christmas, the South Australian House of Assembly voted on the third reading of the Constitution Amendment Bill: ‘The Ayes were sonorous and cheery, the Noes despondent like muffled bells’. When the result was announced, thirty-one in favour and fourteen against, the House resounded to loud cheering as South Australia’s Parliament acknowledged its decision to give votes to women. The legislation made South Australia one of the first places in the world to admit women to the parliamentary suffrage; it was alone in giving them the right to stand for Parliament. Its passage caused elation, rejoicing and relief among those who had laboured to achieve it, for the Act opened the way for women’s political equality and their fuller participation in public life. Before this Act, one level of rights and responsibilities existed for men, another for women. These were determined under the Constitution of 1855-56, which allowed eligible men over twenty-one years to vote and to stand for election for the House of Assembly. Men over thirty years with further residential and property qualifications were eligible to vote and stand for election to the Legislative Council. The masculine gender only, or the word ‘person’, assumed to be male, was used in the Constitution. Women could neither vote nor stand for Parliament. -

The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other Accounts of Constitution-Makers, Constitutions and Citizenship

The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other accounts of constitution-makers, constitutions and citizenship This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2005 Geoffrey Trenorden BA Honours (Murdoch) Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………………….. Geoffrey Trenorden ii Abstract As argued throughout this thesis, in his personification of the federal story, if not immediately in his formulation of its paternity, Deakin’s unpublished memoirs anticipated the way that federation became codified in public memory. The long and tortuous process of federation was rendered intelligible by turning it into a narrative set around a series of key events. For coherence and dramatic momentum the narrative dwelt on the activities of, and words of, several notable figures. To explain the complex issues at stake it relied on memorable metaphors, images and descriptions. Analyses of class, citizenship, or the industrial confrontations of the 1890s, are given little or no coverage in Deakinite accounts. Collectively, these accounts are told in the words of the victors, presented in the images of the victors, clothed in the prejudices and predilections of the victors, while the losers are largely excluded. Those who spoke out against or doubted the suitability of the constitution, for whatever reason, have largely been removed from the dominant accounts of constitution-making. More often than not they have been ‘character assassinated’ or held up to public ridicule by Alfred Deakin, the master narrator of the Conventions and federation movement and by his latter-day disciples.