Broken Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Starting a Hedge Fund in the Sophomore Year

FEATURING:FEATURING:THETHE FALL 2001 COUNTRY CREDIT RATINGSANDTHE WORLD’S BEST HOTELS SEPTEMBER 2001 BANKING ON DICK KOVACEVICH THE HARD FALL OF HOTCHKIS & WILEY MAKING SENSE OF THE ECB PLUS: IMF/WorldBank Special Report THE EDUCATION OF HORST KÖHLER CAVALLO’S BRINKMANSHIP CAN TOLEDO REVIVE PERU? THE RESURGENCE OF BRAZIL’S LEFT INCLUDING: MeetMeet The e-finance quarterly with: CAN CONSIDINE TAKE DTCC GLOBAL? WILLTHE RACE KenGriffinKenGriffin GOTO SWIFT? Just 32, he wants to run the world’s biggest and best hedge fund. He’s nearly there. COVER STORY en Griffin was desperate for a satellite dish, but unlike most 18-year-olds, he wasn’t looking to get an unlimited selection of TV channels. It was the fall of 1987, and the Harvard College sophomore urgently needed up-to-the-minute stock quotes. Why? Along with studying economics, he hap- pened to be running an investment fund out of his third-floor dorm room in the ivy-covered turn- of-the-century Cabot House. KTherein lay a problem. Harvard forbids students from operating their own businesses on campus. “There were issues,” recalls Julian Chang, former senior tutor of Cabot. But Griffin lobbied, and Cabot House decided that the month he turns 33. fund, a Florida partnership, was an off-campus activity. So Griffin’s interest in the market dates to 1986, when a negative Griffin put up his dish. “It was on the third floor, hanging out- Forbes magazine story on Home Shopping Network, the mass side his window,” says Chang. seller of inexpensive baubles, piqued his interest and inspired him Griffin got the feed just in time. -

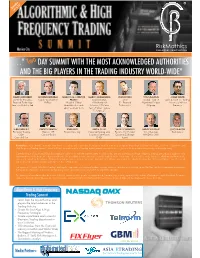

International Algorithmic and High Frequency Trading Summit

TH NovemberTH & 15 14 Mexico City WWW.RISKMATHICS.COM …” Two DAY SUMMIT WITH THE MOST ACKNOWLEDGED AUTHORITIES AND THE BIG PLAYERS IN THE TRADING INDUSTRY WORLD-WIDE” DAVID LEINWEBER GEORGE KLEDARAS MARCOS M. LÓPEZ DE MARCO AVELLANEDA DAN ROSEN YOUNG KANG JORGE NEVID Center for Innovative Founder & Chairman PRADO Courant Institute CEO Global Head of Sales & Electronic Trading Financial Technology FixFlyer Head of Global of Mathematical R2 Financial Algorithmic Products Acciones y Valores Lawrence Berkeley Lab Quantitative Research Sciences, NYU and Technologies Citigroup Banamex Tudor Investment Corp. Senior Partner, Finance Concepts LLC SEBASTIÁN REY CARLOS RAMÍREZ JOHN HULL KARLA SILLER VASSILIS VERGOTIS SANDY FRUCHER JULIO BEATON Electronic Trading Banorte - IXE Toronto University National Banking and Executive Vice President Vice Chairman TradeStation GBM Casa de Bolsa Securities Commission European Exchange NASDAQ OMX Casa de Bolsa CNBV (Eurex) RiskMathics, aware that the most important factor to develop and consolidate the financial markets is training and promoting a high level financial culture, will host: “Algorithmic and High Frequency Trading Summit”, which will have the participation of leading market practitioners who have key roles in the financial industry locally and internationally. Currently the use of Automated/Black-Box trading in combination with the extreme speed in which orders are sent and executed (High Frequency Trading) are without a doubt the most important trends in the financial industry world-wide. The possibility to have direct access to the markets and to send burst orders in milliseconds, has been a fundamental factor in the exponential growth in the number of transactions that we have seen in recent years. -

Electronic Call Market Trading Nicholas Economides and Robert A

VOLUME 21 NUMBER 3 SPRING 1995 Electronic Call Market Trading Nicholas Economides and Robert A. Schwartz Hidden Limit Orders on the NYSE Thomas H.Mclnish and Robert A. Wood Benchmark Orthogonality Properties David E. Tierney and Jgery K Bailey - Equity Style ClassXcations Jon A. Christophmon "'Equity Style Classi6ications": Comment Charles A. Trzn'nka Corporate Governance: There's Danger in New Orthodoxies Bevis Longstreth Industry and Country EfZ'ects in International Stock Returns StmL. Heston and K. Ceert Routuenhont Currency Risk in International Portfolios: How Satisfying is Optimal Hedging? Grant W Gardner and Thieny Wuilloud Fundamental Analysis, Stock Prices, and the Demise of Miniscribe Corporation Philip D. Drake and John W Peavy, LLI Market Timing Can Work in the Real World Glen A. Lmm,Jt., and Gregory D. Wozniak "Market Timing Can Work in the Real World": Comment Joe Brocato and ER. Chandy Testing PSR Filters with the Stochastic Dominance Approach Tung Liang Liao and Peter Shyan-Rong Chou Diverfication Benefits for Investors in Real Estate Susan Hudson- Wonand Bernard L. Elbaum A PUBLICATION OF INSTITUTIONAL INVESTOR, INC. Electronic Call Market Trading Let competition increase @n'ency. Nicholas Economides and Robert A. Schwartz ince Toronto became the first stock exchange to computerize its execution system in 1977, electronic trading has been instituted in Tokyo S(1 982), Paris (1986), Australia (1990), Germany (1991). Israel (1991), Mexico (1993). Switzerland (1995), and elsewhere around the globe. Quite likely, by the year 2000, floor trading will be totally eliminat- ed in Europe, predominantly in favor of electronic con- tinuous markets. Some of the new electronic systems are call mar- kets, however, including the Tel Aviv StockExchange, the Paris Bourse (for thinner issues), and the Bolsa Mexicana's intermediate market. -

Evidence from Illegal Insider Trading Tips

Journal of Financial Economics 125 (2017) 26–47 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Financial Economics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jfec Information networks: Evidence from illegal insider trading R tips Kenneth R. Ahern Marshall School of Business, University of Southern California, 701 Exposition Boulevard, Ste. 231, Los Angeles, CA 90089-1422, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: This paper exploits a novel hand-collected data set to provide a comprehensive analysis Received 20 April 2015 of the social relationships that underlie illegal insider trading networks. I find that in- Revised 15 February 2016 side information flows through strong social ties based on family, friends, and geographic Accepted 15 March 2016 proximity. On average, inside tips originate from corporate executives and reach buy-side Available online 11 May 2017 investors after three links in the network. Inside traders earn prodigious returns of 35% JEL Classification: over 21 days, with more central traders earning greater returns, as information conveyed D83 through social networks improves price efficiency. More broadly, this paper provides some D85 of the only direct evidence of person-to-person communication among investors. G14 ©2017 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. K42 Z13 Keywords: Illegal insider trading Information networks Social networks 1. Introduction cation between investors ( Stein, 2008; Han and Yang, 2013; Andrei and Cujean, 2015 ). The predictions of these mod- Though it is well established that new information els suggest that the diffusion of information over social moves stock prices, it is less certain how information networks is crucial for many financial outcomes, such as spreads among investors. -

New Approach to the Regulation of Trading Across Securities Markets, A

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VoLuME 71 DECEMBER 1996 - NUM-BER 6 A NEW APPROACH TO THE REGULATION OF TRADING ACROSS SECURITIES MARKETS YAKOV AMImHU* HAIM IVIENDELSON** In this Article, ProfessorsAmihud and Mendelson propose that a securities issuer should have the exclusive right to determine in which markets its securities will be traded, in contrast to the current regulatoryscheme under which markets may uni- laterally enable trading in securities without issuer consent Professors Amihud and Mendelson demonstrate that the tradingregime of a security affects its liquidity, and consequently its value, and that multinmarket tradingby some securitiesholders may produce negative externalities that harm securities holders collectively. Under the current scheme; some markets compete for orderflow from individuals by low- eringstandards, thereby creatingthe need for regulatoryoversight. A rule requiring issuer consent would protect the liquidity interests of issuers and of securitieshold- ers as a group. ProfessorsAmihud and Mendelson addresstie treatment of deriva- tive securities under their scheme, proposing a fair use test that would balance the issuer's liquidity interest against the public's right to use price information freely. The authors suggest that under their proposed rule, markets will compete to attract securities issuers by implementing and enforcing value-maximizing trading rules, thereby providing a market-based solution to market regulation. * Professor and Yamaichi Faculty Fellow, Stern School of Business, New York Univer- sity. B.S.S., 1969, Hebrew University, M.B.A., 1973, New York University, Ph.D., 1975. New York University. ** The James Irvin Miller Professor, Stanford Business School, Stanford University. B.Sc., 1972, Hebrew University, M.Sc., 1977, Tel Aviv University; Ph.D., 1979, Tel Aviv University. -

March 25, 2015 Financial Stability Oversight Council

March 25, 2015 Submitted via electronic filing: www.regulations.gov Financial Stability Oversight Council Attention: Patrick Pinschmidt, Deputy Assistant Secretary 1500 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20220 Re: Notice Seeking Comment on Asset Management Products and Activities (FSOC 2014-0001) Dear Financial Stability Oversight Council: BlackRock, Inc. (together with its affiliates, “BlackRock”)1 appreciates the opportunity to respond to the Financial Stability Oversight Council (“Council”) Notice Seeking Comment on Asset Management Products and Activities (“Request for Comment”). BlackRock supports efforts to promote resilient and transparent financial markets, which are in the best interests of all market participants. We are encouraged by the Council’s focus on assessing asset management products and activities, particularly given our view that asset managers do not present systemic risk at the company level, and focusing on individual entities will not address the products and activities that could pose risk to the system as a whole. We have been actively engaged in the dialogue around many of the issues raised in the Request for Comment. We have written extensively on many of these issues (see the list of our relevant publications in Appendix A). Our papers seek to provide information to policy makers and other interested parties about asset management issues. In aggregate, these papers provide background information and data on a variety of topics, such as exchange traded funds (“ETFs”), securities lending, fund structures, and liquidity risk management. In these papers, we also provide recommendations for improving the financial ecosystem for all market participants. All of these papers are available on our website (http://www.blackrock.com/corporate/en-us/news-and- insights/public-policy). -

Rajat Gupta's Trial: the Case for Civil Charges

http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/jurisprudence/2012/05/rajat_gupta_s_trial_the_case_for_civil_charges_against_him_.html Rajat Gupta’s trial: The case for civil charges against him. By Harlan J. Protass | Posted Friday, May 18, 2012, at 8:00 AM ET | Posted Friday, May 18, 2012, at 8:00 AM ET Slate.com Take Their Money and Run The government should fine the hell out of Rajat Gupta instead of criminally prosecuting him. Rajat Gupta, former Goldman Sachs board member, leaves a Manhattan court after surrendering to federal authorities Oct. 26, 2011 in New York City Photograph by Spencer Platt/Getty Images. On Monday, former McKinsey & Company chief executive Rajat Gupta goes on trial for insider trading. Gupta is accused of sharing secrets about Goldman Sachs and Proctor & Gamble with Raj Rajaratnam, the former chief of hedge fund giant Galleon Group, who was convicted in October 2011 of the same crime. Gupta and Rajaratnam are the biggest names in the government’s 3-year-old crackdown on illegal trading on Wall Street. So far, prosecutors have convicted or elicited guilty pleas from more than 60 traders, hedge fund managers, and other professionals. Federal authorities said in February that they are investigating an additional 240 people for trading on inside information. About one half have been identified as “targets,” meaning that government agents believe they committed crimes and are building cases against them. Officials are so serious about their efforts that they even produced a public service announcement about fraud in the public markets. It features Michael Douglas, the Academy Award winning actor who played corrupt financier Gordon Gekko in the 1987 hit film Wall Street. -

Hedge Fund and Private Equity Fund: Structures, Regulation and Criminal Risks

Hedge Fund and Private Equity Fund: Structures, Regulation and Criminal Risks Duff & Phelps, LLC Ann Gittleman, Managing Director Norman Harrison, Managing Director Speakers Ann Gittleman is a managing director Norman Harrison is a managing for the Disputes and Investigations director at Duff & Phelps based in practice. She focuses on providing expert Washington, D.C. As a former corporate forensic and dispute assistance in fraud attorney, investment banker and and internal investigations, white collar investment fund principal, he has a wide investigations and compliance reviews. range of experience at the intersection of She is experienced in accounting and regulation and the capital markets. Mr. auditor malpractice matters, and related Harrison advises clients in post-closing Generally Accepted Accounting Principles disputes, securities enforcement and (GAAP) and Generally Accepted Auditing financial fraud investigations, and fiduciary Standards (GAAS) guidance and duty and corporate governance matters. damages. She has worked on U.S. He also consults with investment funds regulatory investigations involving the and their portfolio companies on Securities and Exchange Commission operations, risk management, due (SEC) and the Department of Justice diligence and compliance issues, and (DOJ). advises institutional fund investors in reviewing potential private equity and Furthermore, she has a background in forensic accounting, asset tracing, hedge fund sub-advisors commercial disputes, commercial damages, and lost profits analysis. Ann works on bankruptcy investigations, as a financial advisor in U.S. Norman has conducted numerous internal investigations in matters arising bankruptcies, purchase price and post-acquisition disputes, and Foreign from federal investigations, shareholder allegations, media exposés and Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) reviews. other circumstances. -

Shearman & Sterling's White Collar Group Named a Law360 Practice

Portfolio Media. Inc. | 860 Broadway, 6th Floor | New York, NY 10003 | www.law360.com Phone: +1 646 783 7100 | Fax: +1 646 783 7161 | [email protected] White Collar Group Of The Year: Shearman & Sterling By Dietrich Knauth Law360, New York (January 21, 2014, 7:41 PM ET) -- Shearman & Sterling LLP secured two acquittals in the prosecution of price-fixing in the liquid crystal display flat-screen industry and is engaged in a closely watched appeal that could affect the way hedge fund executives are prosecuted under insider trading laws, earning the firm a place among Law360's White Collar Practice Groups of 2013. With more than 60 litigators who regularly handle white collar cases, the firm is able to offer its clients top-notch defenses in a broad range of areas including price-fixing, insider trading, stock market manipulation and Foreign Corrupt Practices Act violations, according to Adam Hakki, global head of the firm’s litigation group. Shearman & Sterling has built a team of experienced litigators and backs up its courtroom skills by leveraging its international presence and expertise in the financial industry, Hakki said. Hakki, who guided Galleon Group through the landmark insider trading case that sent Galleon founder Raj Rajaratnam to prison and involved unprecedented use of wiretaps, said the firm's frequent representation of financial companies and hedge funds gives it an edge when those companies find themselves tangled in criminal investigations. “We live and breathe in that space, and we think it makes a big difference because we aren't learning on the job when we take on a white collar matter,” Hakki said. -

Market Mechanics: a Guide to U.S

BRCM CDWC CEFT CEPH CHIR CHKP CHTR CIEN CMCSK CMVT CNXT COST CPWR CSCO CTAS CTXS CYTC DELL Market Mechanics: A Guide to U.S. Stock Markets release 1.2 Although the inner workings of the stock market are fas- cinating, few introductory texts have the space to describe them in detail. Furthermore, the U.S. stock markets have been chang- ing so rapidly in recent years that many books have not yet caught up with the changes. This quick note provides an up-to- date view of how the U.S. stock markets work today. This note will teach you about: • The functions of a stock market; • Stock markets in the United States, including Nasdaq JAMES J. ANGEL, Ph.D. and the NYSE; Associate Professor of Finance • The difference between limit and market orders; McDonough School of Business • How stock trades take place; and Georgetown University • Lots of other interesting tidbits about the stock market that you wanted to know, but were afraid to ask. Market Mechanics: A Guide to U.S. Stock Markets DISH EBAY ERICY ERTS ESRX FISV FLEX GENZ GILD GMST HGSI ICOS IDPH IDTI IMCL IMNX INTC INTU ITWO What a Stock Market Does most productive opportunities are. These signals channel The stock market provides a mechanism where people capital to the areas that investors think are most produc- who want to own shares of stock can buy them from peo- tive. Finally, the financial markets provide important risk- ple who already own those shares. This mechanism not management tools by letting investors diversify their only matches buyer and seller, but it also provides a way investments and transfer risk from those less able to toler- for the buyer and seller to agree mutually on the price. -

Hedge Funds for Investors

Chapter 6 Individual Factors: Moral Philosophies and Values Frauds of the Century Ponzi vs. Pyramid Schemes Ponzi scheme: A type of white-collar crime that occurs when a criminal—often of high repute— takes money from new investors to pay earnings for existing investors. The money is never actually invested and, when the scheme finally collapses, newer investors usually lose their investments. Ponzi vs. Pyramid Schemes Ponzi scheme: This type of fraud is highly detrimental to society Huge financial impact Displaces consumer trust in business. Despite the high-profile cases like Bernard Madoff, Tom Petters, and R. Allen Stanford, Ponzi schemes continue to be used in any industry that includes investing. Ponzi vs. Pyramid Schemes Pyramid scheme: Offers an opportunity for an individual to make money that requires effort. Usually this is in the form of an investment, business, or product opportunity This type of fraud is highly detrimental to society. The first person recruited then sells or recruits more people, and a type of financial reward is given to those who recruit the next participant. Ponzi vs. Pyramid Schemes Pyramid scheme: The key aspect of a pyramid scheme is that people pay for getting involved. Each new individual or investor joins in what is believed to be a legitimate opportunity to get a return, which is how the fraudster gets money. Unlike a legitimate organization, pyramid schemes either do not sell a product, or the investment is almost worthless. All income comes from new people enrolling. Ponzi vs. Pyramid Schemes Pyramid scheme: Direct selling businesses that employ a multilevel marketing compensation system are often accused of being pyramid schemes because of similarities in business structure, although multilevel marketing is a compensation method that involves selling a legitimate product. -

Hedge Funds and Systemic Risk

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Hedge Funds and Systemic Risk Lloyd Dixon, Noreen Clancy, Krishna B. Kumar C O R P O R A T I O N The research described in this report was supported by a contribution by Christopher D.