GC and CCO Risks and Safeguards: Ethics in Practice Marc E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here a Causal Relationship? Contemporary Economics, 9(1), 45–60

Bibliography on Corruption and Anticorruption Professor Matthew C. Stephenson Harvard Law School http://www.law.harvard.edu/faculty/mstephenson/ March 2021 Aaken, A., & Voigt, S. (2011). Do individual disclosure rules for parliamentarians improve government effectiveness? Economics of Governance, 12(4), 301–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-011-0100-8 Aaronson, S. A. (2011a). Does the WTO Help Member States Clean Up? Available at SSRN 1922190. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1922190 Aaronson, S. A. (2011b). Limited partnership: Business, government, civil society, and the public in the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). Public Administration and Development, 31(1), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.588 Aaronson, S. A., & Abouharb, M. R. (2014). Corruption, Conflicts of Interest and the WTO. In J.-B. Auby, E. Breen, & T. Perroud (Eds.), Corruption and conflicts of interest: A comparative law approach (pp. 183–197). Edward Elgar PubLtd. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebookbatch.GEN_batch:ELGAR01620140507 Abbas Drebee, H., & Azam Abdul-Razak, N. (2020). The Impact of Corruption on Agriculture Sector in Iraq: Econometrics Approach. IOP Conference Series. Earth and Environmental Science, 553(1), 12019-. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/553/1/012019 Abbink, K., Dasgupta, U., Gangadharan, L., & Jain, T. (2014). Letting the briber go free: An experiment on mitigating harassment bribes. JOURNAL OF PUBLIC ECONOMICS, 111(Journal Article), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.12.012 Abbink, Klaus. (2004). Staff rotation as an anti-corruption policy: An experimental study. European Journal of Political Economy, 20(4), 887–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2003.10.008 Abbink, Klaus. -

Starting a Hedge Fund in the Sophomore Year

FEATURING:FEATURING:THETHE FALL 2001 COUNTRY CREDIT RATINGSANDTHE WORLD’S BEST HOTELS SEPTEMBER 2001 BANKING ON DICK KOVACEVICH THE HARD FALL OF HOTCHKIS & WILEY MAKING SENSE OF THE ECB PLUS: IMF/WorldBank Special Report THE EDUCATION OF HORST KÖHLER CAVALLO’S BRINKMANSHIP CAN TOLEDO REVIVE PERU? THE RESURGENCE OF BRAZIL’S LEFT INCLUDING: MeetMeet The e-finance quarterly with: CAN CONSIDINE TAKE DTCC GLOBAL? WILLTHE RACE KenGriffinKenGriffin GOTO SWIFT? Just 32, he wants to run the world’s biggest and best hedge fund. He’s nearly there. COVER STORY en Griffin was desperate for a satellite dish, but unlike most 18-year-olds, he wasn’t looking to get an unlimited selection of TV channels. It was the fall of 1987, and the Harvard College sophomore urgently needed up-to-the-minute stock quotes. Why? Along with studying economics, he hap- pened to be running an investment fund out of his third-floor dorm room in the ivy-covered turn- of-the-century Cabot House. KTherein lay a problem. Harvard forbids students from operating their own businesses on campus. “There were issues,” recalls Julian Chang, former senior tutor of Cabot. But Griffin lobbied, and Cabot House decided that the month he turns 33. fund, a Florida partnership, was an off-campus activity. So Griffin’s interest in the market dates to 1986, when a negative Griffin put up his dish. “It was on the third floor, hanging out- Forbes magazine story on Home Shopping Network, the mass side his window,” says Chang. seller of inexpensive baubles, piqued his interest and inspired him Griffin got the feed just in time. -

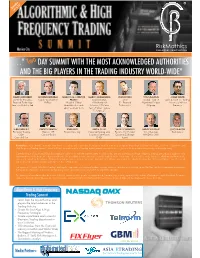

International Algorithmic and High Frequency Trading Summit

TH NovemberTH & 15 14 Mexico City WWW.RISKMATHICS.COM …” Two DAY SUMMIT WITH THE MOST ACKNOWLEDGED AUTHORITIES AND THE BIG PLAYERS IN THE TRADING INDUSTRY WORLD-WIDE” DAVID LEINWEBER GEORGE KLEDARAS MARCOS M. LÓPEZ DE MARCO AVELLANEDA DAN ROSEN YOUNG KANG JORGE NEVID Center for Innovative Founder & Chairman PRADO Courant Institute CEO Global Head of Sales & Electronic Trading Financial Technology FixFlyer Head of Global of Mathematical R2 Financial Algorithmic Products Acciones y Valores Lawrence Berkeley Lab Quantitative Research Sciences, NYU and Technologies Citigroup Banamex Tudor Investment Corp. Senior Partner, Finance Concepts LLC SEBASTIÁN REY CARLOS RAMÍREZ JOHN HULL KARLA SILLER VASSILIS VERGOTIS SANDY FRUCHER JULIO BEATON Electronic Trading Banorte - IXE Toronto University National Banking and Executive Vice President Vice Chairman TradeStation GBM Casa de Bolsa Securities Commission European Exchange NASDAQ OMX Casa de Bolsa CNBV (Eurex) RiskMathics, aware that the most important factor to develop and consolidate the financial markets is training and promoting a high level financial culture, will host: “Algorithmic and High Frequency Trading Summit”, which will have the participation of leading market practitioners who have key roles in the financial industry locally and internationally. Currently the use of Automated/Black-Box trading in combination with the extreme speed in which orders are sent and executed (High Frequency Trading) are without a doubt the most important trends in the financial industry world-wide. The possibility to have direct access to the markets and to send burst orders in milliseconds, has been a fundamental factor in the exponential growth in the number of transactions that we have seen in recent years. -

Regulation of Dietary Supplements Hearing

S. HRG. 108–997 REGULATION OF DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 28, 2003 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 20–196 PDF WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 11:04 May 24, 2016 Jkt 075679 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\DOCS\20196.TXT JACKIE SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona, Chairman TED STEVENS, Alaska ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina, CONRAD BURNS, Montana Ranking TRENT LOTT, Mississippi DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas JOHN B. BREAUX, Louisiana GORDON SMITH, Oregon BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota PETER G. FITZGERALD, Illinois RON WYDEN, Oregon JOHN ENSIGN, Nevada BARBARA BOXER, California GEORGE ALLEN, Virginia BILL NELSON, Florida JOHN E. SUNUNU, New Hampshire MARIA CANTWELL, Washington FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey JEANNE BUMPUS, Republican Staff Director and General Counsel ROBERT W. CHAMBERLIN, Republican Chief Counsel KEVIN D. KAYES, Democratic Staff Director and Chief Counsel GREGG ELIAS, Democratic General Counsel (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 11:04 May 24, 2016 Jkt 075679 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\GPO\DOCS\20196.TXT JACKIE C O N T E N T S Page Hearing held on October 28, 2003 ......................................................................... -

Reggie Huff, Et Al Vs. Firstenergy Corp., Et Al

Case: 5:12-cv-02583-SL Doc #: 31 Filed: 09/17/13 1 of 41. PageID #: <pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF OHIO EASTERN DIVISION REGGIE HUFF, et al., ) CASE NO. 5:12CV2583 ) PLAINTIFFS, ) JUDGE SARA LIOI ) vs. ) ) MEMORANDUM OPINION ) ) FIRSTENERGY CORP., et al., ) ) DEFENDANTS. ) On October 16, 2012, plaintiffs, Reggie Huff and Lisa Huff, filed a pro se complaint in this Court alleging: violations of the federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (“federal RICO”), 18 U.S.C. §§ 1962(b), (c), and (d); violations of Ohio’s “corrupt activity” law (“Ohio RICO”), Ohio Rev. Code § 2923.32;1 conspiracy under federal and Ohio law; and violations of their civil rights under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 (Doc. No. 1, Complaint). Plaintiffs originally named eleven defendants (not counting John Doe defendants), including corporate entities, private individuals, and current and former Ohio Supreme Court justices. The complaint further alleged a vast conspiracy to deprive plaintiffs of their right to a fair disposition of a personal injury action in state court. The allegations in the 43-page complaint are confusing, rambling, and, at times, inflammatory. Although much thought and attention appears to have gone into its 1 Ohio Rev. Code § 2923.34 provides individuals with a civil cause of action for violations of § 2923.32, which is otherwise a criminal statute. Case: 5:12-cv-02583-SL Doc #: 31 Filed: 09/17/13 2 of 41. PageID #: <pageID> preparation, the complaint is ultimately held together by a string of conclusory allegations.2 These allegations were immediately met with a motion to dismiss (Doc. -

SENATE—Wednesday, March 21, 2012

March 21, 2012 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 158, Pt. 3 3753 SENATE—Wednesday, March 21, 2012 The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was SCHEDULE The uninsured people show up at hos- called to order by the Honorable Mr. REID. Madam President, fol- pitals. They are not pushed away; they KIRSTEN E. GILLIBRAND, a Senator from lowing leader remarks the Senate will are invited in. They receive the treat- the State of New York. be in a period of morning business for ment. Then they can’t pay for it. 1 hour, with the majority controlling It turns out that 63 percent of the PRAYER the first half and the Republicans con- medical care given to uninsured people The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- trolling the final half. in America isn’t paid for—not by them. fered the following prayer: Following morning business the Sen- It turns out the rest of us pay for it. Let us pray. ate will resume consideration of the Everyone else in America who has O God, who loves us without ceasing, capital formation bill. At approxi- health insurance has to pick up the we turn our thoughts toward You. Re- mately 10:40 this morning, there will be cost for those who did not accept their main with our Senators today so that a cloture vote on the IPO bill. personal responsibility to buy health for no single instance they will be un- insurance. f aware of Your providential power. So, so what? What difference does We thank You for Your infinite love RESERVATION OF LEADER TIME that make? It makes a difference. -

Evidence from Illegal Insider Trading Tips

Journal of Financial Economics 125 (2017) 26–47 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Financial Economics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jfec Information networks: Evidence from illegal insider trading R tips Kenneth R. Ahern Marshall School of Business, University of Southern California, 701 Exposition Boulevard, Ste. 231, Los Angeles, CA 90089-1422, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: This paper exploits a novel hand-collected data set to provide a comprehensive analysis Received 20 April 2015 of the social relationships that underlie illegal insider trading networks. I find that in- Revised 15 February 2016 side information flows through strong social ties based on family, friends, and geographic Accepted 15 March 2016 proximity. On average, inside tips originate from corporate executives and reach buy-side Available online 11 May 2017 investors after three links in the network. Inside traders earn prodigious returns of 35% JEL Classification: over 21 days, with more central traders earning greater returns, as information conveyed D83 through social networks improves price efficiency. More broadly, this paper provides some D85 of the only direct evidence of person-to-person communication among investors. G14 ©2017 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. K42 Z13 Keywords: Illegal insider trading Information networks Social networks 1. Introduction cation between investors ( Stein, 2008; Han and Yang, 2013; Andrei and Cujean, 2015 ). The predictions of these mod- Though it is well established that new information els suggest that the diffusion of information over social moves stock prices, it is less certain how information networks is crucial for many financial outcomes, such as spreads among investors. -

March 25, 2015 Financial Stability Oversight Council

March 25, 2015 Submitted via electronic filing: www.regulations.gov Financial Stability Oversight Council Attention: Patrick Pinschmidt, Deputy Assistant Secretary 1500 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20220 Re: Notice Seeking Comment on Asset Management Products and Activities (FSOC 2014-0001) Dear Financial Stability Oversight Council: BlackRock, Inc. (together with its affiliates, “BlackRock”)1 appreciates the opportunity to respond to the Financial Stability Oversight Council (“Council”) Notice Seeking Comment on Asset Management Products and Activities (“Request for Comment”). BlackRock supports efforts to promote resilient and transparent financial markets, which are in the best interests of all market participants. We are encouraged by the Council’s focus on assessing asset management products and activities, particularly given our view that asset managers do not present systemic risk at the company level, and focusing on individual entities will not address the products and activities that could pose risk to the system as a whole. We have been actively engaged in the dialogue around many of the issues raised in the Request for Comment. We have written extensively on many of these issues (see the list of our relevant publications in Appendix A). Our papers seek to provide information to policy makers and other interested parties about asset management issues. In aggregate, these papers provide background information and data on a variety of topics, such as exchange traded funds (“ETFs”), securities lending, fund structures, and liquidity risk management. In these papers, we also provide recommendations for improving the financial ecosystem for all market participants. All of these papers are available on our website (http://www.blackrock.com/corporate/en-us/news-and- insights/public-policy). -

Rajat Gupta's Trial: the Case for Civil Charges

http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/jurisprudence/2012/05/rajat_gupta_s_trial_the_case_for_civil_charges_against_him_.html Rajat Gupta’s trial: The case for civil charges against him. By Harlan J. Protass | Posted Friday, May 18, 2012, at 8:00 AM ET | Posted Friday, May 18, 2012, at 8:00 AM ET Slate.com Take Their Money and Run The government should fine the hell out of Rajat Gupta instead of criminally prosecuting him. Rajat Gupta, former Goldman Sachs board member, leaves a Manhattan court after surrendering to federal authorities Oct. 26, 2011 in New York City Photograph by Spencer Platt/Getty Images. On Monday, former McKinsey & Company chief executive Rajat Gupta goes on trial for insider trading. Gupta is accused of sharing secrets about Goldman Sachs and Proctor & Gamble with Raj Rajaratnam, the former chief of hedge fund giant Galleon Group, who was convicted in October 2011 of the same crime. Gupta and Rajaratnam are the biggest names in the government’s 3-year-old crackdown on illegal trading on Wall Street. So far, prosecutors have convicted or elicited guilty pleas from more than 60 traders, hedge fund managers, and other professionals. Federal authorities said in February that they are investigating an additional 240 people for trading on inside information. About one half have been identified as “targets,” meaning that government agents believe they committed crimes and are building cases against them. Officials are so serious about their efforts that they even produced a public service announcement about fraud in the public markets. It features Michael Douglas, the Academy Award winning actor who played corrupt financier Gordon Gekko in the 1987 hit film Wall Street. -

Hedge Fund and Private Equity Fund: Structures, Regulation and Criminal Risks

Hedge Fund and Private Equity Fund: Structures, Regulation and Criminal Risks Duff & Phelps, LLC Ann Gittleman, Managing Director Norman Harrison, Managing Director Speakers Ann Gittleman is a managing director Norman Harrison is a managing for the Disputes and Investigations director at Duff & Phelps based in practice. She focuses on providing expert Washington, D.C. As a former corporate forensic and dispute assistance in fraud attorney, investment banker and and internal investigations, white collar investment fund principal, he has a wide investigations and compliance reviews. range of experience at the intersection of She is experienced in accounting and regulation and the capital markets. Mr. auditor malpractice matters, and related Harrison advises clients in post-closing Generally Accepted Accounting Principles disputes, securities enforcement and (GAAP) and Generally Accepted Auditing financial fraud investigations, and fiduciary Standards (GAAS) guidance and duty and corporate governance matters. damages. She has worked on U.S. He also consults with investment funds regulatory investigations involving the and their portfolio companies on Securities and Exchange Commission operations, risk management, due (SEC) and the Department of Justice diligence and compliance issues, and (DOJ). advises institutional fund investors in reviewing potential private equity and Furthermore, she has a background in forensic accounting, asset tracing, hedge fund sub-advisors commercial disputes, commercial damages, and lost profits analysis. Ann works on bankruptcy investigations, as a financial advisor in U.S. Norman has conducted numerous internal investigations in matters arising bankruptcies, purchase price and post-acquisition disputes, and Foreign from federal investigations, shareholder allegations, media exposés and Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) reviews. other circumstances. -

Shearman & Sterling's White Collar Group Named a Law360 Practice

Portfolio Media. Inc. | 860 Broadway, 6th Floor | New York, NY 10003 | www.law360.com Phone: +1 646 783 7100 | Fax: +1 646 783 7161 | [email protected] White Collar Group Of The Year: Shearman & Sterling By Dietrich Knauth Law360, New York (January 21, 2014, 7:41 PM ET) -- Shearman & Sterling LLP secured two acquittals in the prosecution of price-fixing in the liquid crystal display flat-screen industry and is engaged in a closely watched appeal that could affect the way hedge fund executives are prosecuted under insider trading laws, earning the firm a place among Law360's White Collar Practice Groups of 2013. With more than 60 litigators who regularly handle white collar cases, the firm is able to offer its clients top-notch defenses in a broad range of areas including price-fixing, insider trading, stock market manipulation and Foreign Corrupt Practices Act violations, according to Adam Hakki, global head of the firm’s litigation group. Shearman & Sterling has built a team of experienced litigators and backs up its courtroom skills by leveraging its international presence and expertise in the financial industry, Hakki said. Hakki, who guided Galleon Group through the landmark insider trading case that sent Galleon founder Raj Rajaratnam to prison and involved unprecedented use of wiretaps, said the firm's frequent representation of financial companies and hedge funds gives it an edge when those companies find themselves tangled in criminal investigations. “We live and breathe in that space, and we think it makes a big difference because we aren't learning on the job when we take on a white collar matter,” Hakki said. -

Honest Services Fraud in the Private Sector I-1

Honest Services Fraud in the Private Sector I-1 Honest Services Fraud in the Private Sector Raymond Banoun Catherine Razzano Rajal Patel Lex Urban1 Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft LLP Washington, D.C. Honest services fraud, also known as the “in- standards and requirements for such a prosecution tangible rights” theory of mail and wire fraud, has against a public official have been better defined been the subject of controversy both before and than those involving persons in the private sector. after the Supreme Court’s decision in McNally v. This is understandable as the justification for ap- United States, 483 U.S. 350 (1987). Prior to Mc- plying section 1346 to public officials is evident; Nally, the mail and wire fraud statutes proscribed a violation of honest services by a public official schemes to defraud others of tangible property or through corruption or self-dealing that breaches financial interests, and of the intangible right to “the essence of the political contract.” See United honest services. In the 1970’s and early 1980’s, States v. Jain, 93 F.3d 436, 441 (8th Cir. 1996). prosecutors regularly relied on 18 U.S.C. §§1341 Although Congress may have intended to apply and 1343 to charge public officials or private sec- section 1346 to the private sector, its failure to tor employees for devising such schemes to com- specifically state that intent has left prosecutors mit fraud where either the U.S. mail or interstate with the discretion and ability to criminalize con- wires were used. The McNally decision ended duct in private industry that may not otherwise be this practice by holding that these statutory provi- illegal.