Unit 9 Indian National Congress Formation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 43 Electoral Statistics

CHAPTER 43 ELECTORAL STATISTICS 43.1 India is a constitutional democracy with a parliamentary system of government, and at the heart of the system is a commitment to hold regular, free and fair elections. These elections determine the composition of the Government, the membership of the two houses of parliament, the state and union territory legislative assemblies, and the Presidency and vice-presidency. Elections are conducted according to the constitutional provisions, supplemented by laws made by Parliament. The major laws are Representation of the People Act, 1950, which mainly deals with the preparation and revision of electoral rolls, the Representation of the People Act, 1951 which deals, in detail, with all aspects of conduct of elections and post election disputes. 43.2 The Election Commission of India is an autonomous, quasi-judiciary constitutional body of India. Its mission is to conduct free and fair elections in India. It was established on 25 January, 1950 under Article 324 of the Constitution of India. Since establishment of Election Commission of India, free and fair elections have been held at regular intervals as per the principles enshrined in the Constitution, Electoral Laws and System. The Constitution of India has vested in the Election Commission of India the superintendence, direction and control of the entire process for conduct of elections to Parliament and Legislature of every State and to the offices of President and Vice- President of India. The Election Commission is headed by the Chief Election Commissioner and other Election Commissioners. There was just one Chief Election Commissioner till October, 1989. In 1989, two Election Commissioners were appointed, but were removed again in January 1990. -

India's Domestic Political Setting

Updated July 12, 2021 India’s Domestic Political Setting Overview The BJP and Congress are India’s only genuinely national India, the world’s most populous democracy, is, according parties. In previous recent national elections they together to its Constitution, a “sovereign, socialist, secular, won roughly half of all votes cast, but in 2019 the BJP democratic republic” where the bulk of executive power boosted its share to nearly 38% of the estimated 600 million rests with the prime minister and his Council of Ministers votes cast (to Congress’s 20%; turnout was a record 67%). (the Indian president is a ceremonial chief of state with The influence of regional and caste-based (and often limited executive powers). Since its 1947 independence, “family-run”) parties—although blunted by two most of India’s 14 prime ministers have come from the consecutive BJP majority victories—remains a crucial country’s Hindi-speaking northern regions, and all but 3 variable in Indian politics. Such parties now hold one-third have been upper-caste Hindus. The 543-seat Lok Sabha of all Lok Sabha seats. In 2019, more than 8,000 candidates (House of the People) is the locus of national power, with and hundreds of parties vied for parliament seats; 33 of directly elected representatives from each of the country’s those parties won at least one seat. The seven parties listed 28 states and 8 union territories. The president has the below account for 84% of Lok Sabha seats. The BJP’s power to dissolve this body. A smaller upper house of a economic reform agenda can be impeded in the Rajya maximum 250 seats, the Rajya Sabha (Council of States), Sabha, where opposition parties can align to block certain may review, but not veto, revenue legislation, and has no nonrevenue legislation (see Figure 1). -

Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014

WID.world WORKING PAPER N° 2019/05 Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014 Abhijit Banerjee Amory Gethin Thomas Piketty March 2019 Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014 Abhijit Banerjee, Amory Gethin, Thomas Piketty* January 16, 2019 Abstract This paper combines surveys, election results and social spending data to document the long-run evolution of political cleavages in India. From a dominant- party system featuring the Indian National Congress as the main actor of the mediation of political conflicts, Indian politics have gradually come to include a number of smaller regionalist parties and, more recently, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). These changes coincide with the rise of religious divisions and the persistence of strong caste-based cleavages, while education, income and occupation play little role (controlling for caste) in determining voters’ choices. We find no evidence that India’s new party system has been associated with changes in social policy. While BJP-led states are generally characterized by a smaller social sector, switching to a party representing upper castes or upper classes has no significant effect on social spending. We interpret this as evidence that voters seem to be less driven by straightforward economic interests than by sectarian interests and cultural priorities. In India, as in many Western democracies, political conflicts have become increasingly focused on identity and religious-ethnic conflicts -

Political Parties in India

A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE www.amkresourceinfo.com Political Parties in India India has very diverse multi party political system. There are three types of political parties in Indiai.e. national parties (7), state recognized party (48) and unrecognized parties (1706). All the political parties which wish to contest local, state or national elections are required to be registered by the Election Commission of India (ECI). A recognized party enjoys privileges like reserved party symbol, free broadcast time on state run television and radio in the favour of party. Election commission asks to these national parties regarding the date of elections and receives inputs for the conduct of free and fair polls National Party: A registered party is recognised as a National Party only if it fulfils any one of the following three conditions: 1. If a party wins 2% of seats in the Lok Sabha (as of 2014, 11 seats) from at least 3 different States. 2. At a General Election to Lok Sabha or Legislative Assembly, the party polls 6% of votes in four States in addition to 4 Lok Sabha seats. 3. A party is recognised as a State Party in four or more States. The Indian political parties are categorized into two main types. National level parties and state level parties. National parties are political parties which, participate in different elections all over India. For example, Indian National Congress, Bhartiya Janata Party, Bahujan Samaj Party, Samajwadi Party, Communist Party of India, Communist Party of India (Marxist) and some other parties. State parties or regional parties are political parties which, participate in different elections but only within one 1 www.amkresourceinfo.com A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE state. -

LIST of RECOGNISED NATIONAL PARTIES (As on 11.01.2017)

LIST OF RECOGNISED NATIONAL PARTIES (as on 11.01.2017) Sl. Name of the Name of President/ Address No. Party General secretary 1. Bahujan Samaj Ms. Mayawati, Ms. Mayawati, Party President President Bahujan Samaj Party 4, Gurudwara Rakabganj Road, New Delhi –110001. 2. Bharatiya Janata Shri Amit Anilchandra Shri Amit Anilchandra Shah, Party Shah, President President Bharatiya Janata Party 11, Ashoka Road, New Delhi – 110001 3. Communist Party Shri S. Sudhakar Reddy, Shri S. Sudhakar Reddy, of India General Secretary General Secretary, Communist Party of India Ajoy Bhawan, Kotla Marg, New Delhi – 110002. 4. Communist Party Shri Sitaram Yechury, Shri Sitaram Yechury, of General Secretary General Secretary India (Marxist) Communist Party of India (Marxist) ,A.K.Gopalan Bhawan,27-29, Bhai Vir Singh Marg (Gole Market), New Delhi - 110001 5. Indian National Smt. Sonia Gandhi, Smt. Sonia Gandhi, Congress President President Indian National Congress 24,Akbar Road, New Delhi – 110011 6. Nationalist Shri Sharad Pawar, Shri Sharad Pawar, Congress Party President President Nationalist Congress Party 10, Bishambhar Das Marg, New Delhi-110001. 7. All India Ms. Mamta Banerjee, All India Trinamool Congress, Trinamool Chairperson 30-B, Harish Chatterjee Street, Congress Kolkata-700026 (West Bengal). LIST OF STATE PARTIES (as on 11.01.2017) S. No. Name of the Name of President/ Address party General Secretary 1. All India Anna The General Secretary- No. 41, Kothanda Raman Dravida Munnetra in-charge Street, Chennai-600021, Kazhagam (Tamil Nadu). (Puratchi Thalaivi Amma), 2. All India Anna The General Secretary- No.5, Fourth Street, Dravida Munnetra in-charge Venkatesware Nagar, Kazhagam (Amma), Karpagam Gardens, Adayar, Chennai-600020, (Tamil Nadu). -

Theosophy and the Origins of the Indian National Congress

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title Theosophy and the Origins of the Indian National Congress Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/73b4862g Journal International Journal of Hindu Studies, 7 Author Bevir, Mark Publication Date 2003 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THEOSOPHY AND THE ORIGINS OF THE INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS By Mark Bevir Department of Political Science University of California, Berkeley Berkeley CA 94720 USA [E-mail: [email protected]] ABSTRACT A study of the role of theosophy in the formation of the Indian National Congress enhances our understanding of the relationship between neo-Hinduism and political nationalism. Theosophy, and neo-Hinduism more generally, provided western-educated Hindus with a discourse within which to develop their political aspirations in a way that met western notions of legitimacy. It gave them confidence in themselves, experience of organisation, and clear intellectual commitments, and it brought them together with liberal Britons within an all-India framework. It provided the background against which A. O. Hume worked with younger nationalists to found the Congress. KEYWORDS: Blavatsky, Hinduism, A. O. Hume, India, nationalism, theosophy. 2 REFERENCES CITED Archives of the Theosophical Society, Theosophical Society, Adyar, Madras. Banerjea, Surendranath. 1925. A Nation in the Making: Being the Reminiscences of Fifty Years of Public Life . London: H. Milford. Bharati, A. 1970. "The Hindu Renaissance and Its Apologetic Patterns". In Journal of Asian Studies 29: 267-88. Blavatsky, H.P. 1888. The Secret Doctrine: The Synthesis of Science, Religion and Philosophy . 2 Vols. London: Theosophical Publishing House. ------ 1972. -

Mohandas Gandhi and the Indian Independence Movement

Teacher Overview Objectives: Mohandas Gandhi and the Indian Independence Movement NYS Social Studies Framework Alignment: Key Idea Conceptual Content Specification Objectives Understanding 10.7 DECOLONIZATION 10.7a Independence Students will explore 1. Describe the political, AND NATIONALISM movements in India and Gandhi’s nonviolent social, and economic (1900–2000): Nationalism Indochina developed in nationalist movement and situation in the early 1900s and decolonization response to European nationalist efforts led by the in India. movements employed a control. Muslim League aimed at variety of methods, the masses that resulted in 2. Describe who Mohandas including nonviolent a British-partitioned Gandhi was and what he resistance and armed subcontinent. believed, and identify what struggle. Tensions and actions he took. conflicts often continued after independence as new 3. Explain how India gained challenges arose. its independence from (Standards: 2, 3, 4, 5; Great Britain. Themes: TCC, GEO, SOC, GOV, CIV,) 4. Explain the effects of the Partition of India on the people of India and Pakistan. A Note About the Section on the Partition of India Please make use of the Stanford History Education Group’s materials on the India Partition to engage students in an investigation of primary sources to answer the question: Was the Partition of India a good plan given what people knew at the time? What was the historical context of the Indian Independence Movement? Objective: Describe the political, social, and economic situation in the early 1900s in India. Introduction Directions: Examine the images below and write down what you recall about each Indian history topic. 1556-1605 1658-1707 Akbar the Great Aurangzeb Source Source 1, Source 2 1. -

List of Contesting Candidates Election to the House of the People/Legislative Assembly from the 131-Kal

FORM 7A [See rule 10(1)] List of Contesting Candidates Election to the House of the People/Legislative Assembly From the 131-Kalyanpur (SC) Assembly Constituency Serial Symbol Name of candidate Address of candidate Party Affiliation Numer Allotted 1 2 3 4 5 (i) Candidates of recognised National and State Political Parties Vill.-Saidpur Jahid 1 Abhay Kumar Post-Rupauli, Bahujan Samaj Party Elephant Distt.-Samastipur Vill.-Mantri Jee Tola Shaharbanni, P.o- 2 Prince Raj Shaharbanni, Lok Jan Shakti Party Bungalow P.S.-Alauli, Distt.-Khagaria Vill.-Chakmahi Mujari, P.o.-Sripur Gahar, 3 Maheshwar Hazari Janta Dal (United) Arrow P.S.-Khanpur, Distt.-Samastipur Mohalla-Amirganj, Nationalist Congress 4 Renu Raj Ward No.-04, Clock Party P.S.+P.O.+Disst.-Samastipur (ii) Candidates of registered Political Parties (other than recognised National and State Political Parties) Communist Party of Vill.-Chakdindayal Sari, India Flag with 5 Jibachh Paswan Post-Sari, (Marxist-Leninist) Three Stars Distt.-Samastipur (Liberation) Vill-Mahamada, Gas 6 Nathuni Paswan P.o.-Pusa, Aap Aur Hum Cylinder Distt.-Samastipur Vill.-Hanshanpur Kirat, Post-Muktapur, P.S.- 7 Rajkishor Paswan Bahujan Mukti Party Cot Kalyanpur, Distt.-Samastipur Vill.-Morshand, Ram Prasad Post-Birauli RI, 8 Hind Congress Party Candles Paswan P.S.-Pusa, Distt.-Samastipur Vill.-Musepur, 9 Ram Balak Paswan Post-Nawranj, Shiv Sena Almirah Distt.-Samastipur Vill.-Kudhwa, Post-Kudhwa Barheta, Jharkhand Mukti Air- 10 Vishuni Paswan P.S.-Chakmnehsi, Morcha Conditioner Distt.-Samastipur Vill.+P.o.-Kishanpur -

List of Women Contesting Candidates.Xlsx

List of Women Contesting Candidates DISTRICT CandIdate Age of the AC_NO AC_NAME Name of the Woman Candidate Name of the Party PartyS ymbol NAME Sl. No. Candidate NORTH WEST 1 NERELA 11 SHAMIM Peace Party Ceiling Fan 65 NORTH WEST 6 RITHALA 9 LEELAWATI DEVI Independent Iron 38 NORTH WEST 7 BAWANA 1 KAVITA Nationalist Congress Party Clock 35 NORTH WEST 8 MUNDKA 10 MEENU Bhartiya Janta Dal (Integrated) Hat 28 NORTH WEST 8 MUNDKA 12 RENU BHARTI Rashtravadi Janata Party Auto- Rickshaw 33 NORTH WEST 8 MUNDKA 18 REETA Independent Pressure Cooker 32 NORTH WEST 10 SULTANPUR MAJRA 3 SUSHILA KUMARI Bharatiya Janata Party Lotus 36 NORTH EAST 63 SEEMA PURI 6 DEEP MALA National Lokmat Party Iron 48 NORTH EAST 65 SEELAMPUR 4 NAZRIN NAAZ Peace Party Ceiling Fan 36 NORTH EAST 66 GHONDA 5 KIRAN SINGH Indian Justice Party Television 36 NORTH EAST 67 BABARPUR 5 KESAR Rashtriya Janmorcha Scissors 34 NORTH EAST 67 BABARPUR 10 MAHNAAZ ALAM Independent Table 27 NORTH EAST 67 BABARPUR 11 MS. SHAGUFTA RANI Independent Battery Torch 26 NORTH EAST 68 GOKALPUR 10 SATYENDRI PAL SINGH Samajwadi Party Bicycle 29 NORTH EAST 69 MUSTAFABAD 7 DEVKI MAURYA Loktantrik Samajwadi Party Candles 43 SOUTH 49 SANGAM VIHAR 9 RAMA WATI Rashtriya Manav samman Party Gas Stove 35 SOUTH 49 SANGAM VIHAR 10 RITA GILL Indian Justice Party Television 44 SOUTH 49 SANGAM VIHAR 13 KALPANA JHA Independent Electric Pole 41 SOUTH 51 KALKAJI 8 SUMAN YADAV Samajwadi Party Slate 36 SOUTH 52 TUGHLAKABAD 10 REKHA SINGH Independent Envelope 43 SOUTH 53 BADARPUR 5 CHAMPA DEVI Janata Dal (United) Arrow -

Vital Stats Profile of the 17Th Bihar Legislative Assembly

Vital Stats Profile of the 17th Bihar Legislative Assembly The results of the elections to the 17th Bihar Legislative Assembly were declared today. There are 243 assembly seats in the state. In this context, we analyse data on the profile of the incoming Members of Legislative Assembly (MLAs) and compare it with the previous Assembly. NDA has the majority with 125 seats; RJD is again the single largest party with 75 seats Political Party 2020 2015 Political Party 2020 2015 Rashtriya Janata Dal 75 80 Vikassheel Insaan Party 4 0 Bharatiya Janata Party 74 53 Communist Party of India 2 0 Janata Dal (United) 43 71 Communist Party of India (Marxist) 2 0 Indian National Congress 19 27 Independent 1 4 Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) 12 3 Lok Jan Shakti Party 1 2 (Liberation) All India Majlis-E-Ittehadul Muslimeen 5 0 Bahujan Samaj Party 1 0 Hindustani Awam Morcha (Secular) 4 1 Rashtriya Lok Samata Party 0 2 Number of young MLAs reduces; women’s representation remains similar Gender Profile Age Profile 60% 53% 48% 250 215 217 200 40% 33% 27% 150 20% 16%14% 100 4% 5% 50 28 26 0% 0 25-40 41-55 56-70 Above 70 2015 2020 2015 2020 Male Female 62% of the MLAs have at least a bachelors degree 60% Education Profile 38% 38% 40% 40% 40% 20% 15% 13% 7% 9% 0% Upto Higher Secondary Graduate Post Graduate Doctorate 2015 2020 Sources: Election Commission of India (results.eci.gov.in); Bihar Assembly Website (vidhansabha.bih.nic.in/Knowyourmla.html); Candidate Affidavits uploaded on ECI; PRS. -

The Final Transfer of Power in India, 1937-1947: a Closer Look

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 12-2011 The inF al Transfer of Power in India, 1937-1947: A Closer Look Sidhartha Samanta University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian History Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Samanta, Sidhartha, "The inF al Transfer of Power in India, 1937-1947: A Closer Look" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 258. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/258 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE FINAL TRANSFER OF POWER IN INDIA, 1937-1947: A CLOSER LOOK THE FINAL TRANSFER OF POWER IN INDIA, 1937-1947: A CLOSER LOOK A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Sidhartha Samanta Utkal University Bachelor of Science in Physics, 1989 Utkal University Master of Science in Physics, 1991 University of Arkansas Master of Science in Computer Science, 2007 December 2011 University of Arkansas Abstract The long freedom struggle in India culminated in a victory when in 1947 the country gained its independence from one hundred fifty years of British rule. The irony of this largely non-violent struggle led by Mahatma Gandhi was that it ended in the most violent and bloodiest partition of the country which claimed the lives of two million civilians and uprooted countless millions in what became the largest forced migration of people the world has ever witnessed. -

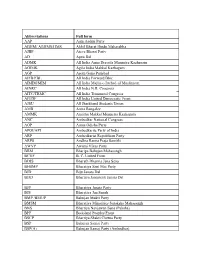

Abbreviations Full Form AAP Aam Aadmi Party ABHM

Abbreviations Full form AAP Aam Aadmi Party ABHM/ ABHMS/HMS Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha AJBP Ajeya Bharat Party AD Apna Dal ADMK All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam AGIMK Agila India Makkal Kazhagam AGP Asom Gana Parishad AIFB/FBL All India Forward Bloc AIMIM/MIM All India Majlis-e-Ittehad-ul Muslimeen AINRC All India N.R. Congress AITC/TRMC All India Trinamool Congress AIUDF All India United Democratic Front AJSU All Jharkhand Students Union AMB Amra Bangalee AMMK Anaithu Makkal Munnetra Kazhagam ANC Ambedkar National Congress AOP Aama Odisha Party APOI/API Ambedkarite Party of India ARP Ambedkarist Republican Party ARPS Andhra Rastra Praja Samithi AWVP Awami Vikas Party BBM Bharipa Bahujan Mahasangh BCUF B. C. United Front BDJS Bharath Dharma Jana Sena BHSMP Bharatiya Sant Mat Party BJD Biju Janata Dal BJJD Bhartiya Jantantrik Janata Dal BJP Bharatiya Janata Party BJS Bharatiya Jan Sangh BMP /BMUP Bahujan Mukti Party BMSM Bharatiya Minorities Suraksha Mahasangh BNS Bhartiya Navjawan Sena (Paksha) BPF Bodoland Peoples Front BSCP Bhartiya Shakti Chetna Party BSP Bahujan Samaj Party BSP(A) Bahujan Samaj Party (Ambedkar) BVA Bahujan Vikas Aaghadi BVM Bharat Vikas Morcha CMP/CMP (J) Communist Marxist party Cong(S) Congress (Secular) CPI Communist Party of India CPI(ML) Red Star Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Red Star CPIML (L) Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist) Liberation CPM Communist Party of India (Marxist) DABP Dalita Bahujana Party DJP Delhi Janta Party DMDK Desiya Murpokku Dravida Kazhagam DMK Dravida Munnetra