The Identity of Architecture and the Architecture of Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arquitecto Y Humanista

50 Nuestros maestros Marcial Gutiérrez Camarena: Arquitecto y humanista Cecilia Gutiérrez Arriola Académica del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas de la UNAM igura predominante en el ámbito de la docencia de la arqui- el periodo virreinal. Su infancia transcurre en la ciudad de Tepic, tectura y la vida académica de la Escuela Nacional de Ar- adonde se muda la familia en busca de una mejor economía, en quitectura de los años cuarenta, a Marcial Gutiérrez tiempos en que el porfiriato agonizaba y estallaba la lucha arma- Camarena aún se le recuerda porque fue un hombre comprome- da. En noviembre de 1919, junto con su hermano Alberto, se tras- tido con su profesión y un universitario entregado a la transmi- ladó a la Ciudad de México, emprendiendo la dificil aventura de sión del conocimiento. dejar la tierra natal y trabajar para poder estudiar. Hizo el ba- Participe de una brillante y privilegiada generación que se chillerato en el Colegio Francés Morelos, de los Maristas, y en formó bajo la égida del padre del Movimiento Moderno y del 1923, ingresó a la Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes, en la vieja gran maestro que fue José Villagrán García, grupo que trascen- Academia de San Carlos, que ya estaba incorporada a la Uni- dió no sólo por el sino por la huella que marcó con sus propues- versidad Nacional, para estudiar la carrera de arquitectura, tas funcionalistas en la arquitectura mexicana. cuando la ciudad de México empezaba a vivir grandes momen- Nació en San Blas, Nayarit, en febrero de1898, cuando su pa- tos en la educación y la cultura, propiciados por el ministro Jo- dre trabajaba para la Casa de comercio Lanzagorta y fungía como sé Vasconcelos. -

Modernism Without Modernity: the Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940 Mauro F

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Management Papers Wharton Faculty Research 6-2004 Modernism Without Modernity: The Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940 Mauro F. Guillen University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/mgmt_papers Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, and the Management Sciences and Quantitative Methods Commons Recommended Citation Guillen, M. F. (2004). Modernism Without Modernity: The Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940. Latin American Research Review, 39 (2), 6-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/lar.2004.0032 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/mgmt_papers/279 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modernism Without Modernity: The Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940 Abstract : Why did machine-age modernist architecture diffuse to Latin America so quickly after its rise in Continental Europe during the 1910s and 1920s? Why was it a more successful movement in relatively backward Brazil and Mexico than in more affluent and industrialized Argentina? After reviewing the historical development of architectural modernism in these three countries, several explanations are tested against the comparative evidence. Standards of living, industrialization, sociopolitical upheaval, and the absence of working-class consumerism are found to be limited as explanations. As in Europe, Modernism -

Title: the Avant-Garde in the Architecture and Visual Arts of Post

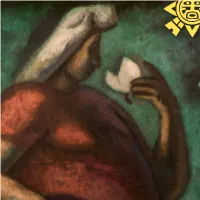

1 Title: The avant-garde in the architecture and visual arts of Post-Revolutionary Mexico Author: Fernando N. Winfield Architecture_media_politics_society. vol. 1, no.3. November 2012 Mexico City / Portrait of an Architect with the City as Background. Painting by Juan O´Gorman (1949). Museum of Modern Art, Mexico. Commenting on an exhibition of contemporary Mexican architecture in Rome in 1957, the polemic and highly influential Italian architectural critic and historian, Bruno Zevi, ridiculed Mexican modernism for combining Pre-Columbian motifs with modern architecture. He referred to it as ‘Mexican Grotesque.’1 Inherent in Zevi’s comments were an attitude towards modern architecture that defined it in primarily material terms; its principle role being one of “spatial and programmatic function.” Despite the weight of this Modernist tendency in the architectural circles of Post-Revolutionary Mexico, we suggest in this paper that Mexican modernism cannot be reduced to such “material” definitions. In the highly charged political context of Mexico in the first half of the twentieth century, modern architecture was perhaps above all else, a tool for propaganda. ARCHITECTURE_MEDIA_POLITICS_SOCIETY Vol. 1, no.3. November 2012 1 2 In this political atmosphere it was undesirable, indeed it was seen as impossible, to separate art, architecture and politics in a way that would be a direct reflection of Modern architecture’s European manifestations. Form was to follow function, but that function was to be communicative as well as spatial and programmatic. One consequence of this “political communicative function” in Mexico was the combination of the “mural tradition” with contemporary architectural design; what Zevi defined as “Mexican Grotesque.” In this paper, we will examine the political context of Post-Revolutionary Mexico and discuss what may be defined as its most iconic building; the Central Library at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico. -

The Casa Cristo Gardens in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2001 Towards Establishing a Process for Preserving Historic Landscapes in Mexico: The aC sa Cristo Gardens in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico Marcela De Obaldia Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Landscape Architecture Commons Recommended Citation De Obaldia, Marcela, "Towards Establishing a Process for Preserving Historic Landscapes in Mexico: The asC a Cristo Gardens in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico" (2001). LSU Master's Theses. 2239. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2239 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOWARDS ESTABLISHING A PROCESS FOR PRESERVING HISTORIC LANDSCAPES IN MEXICO: THE CASA CRISTO GARDENS IN GUADALAJARA, JALISCO, MEXICO. A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Landscape Architecture in The Department of Landscape Architecture by Marcela De Obaldia B.Arch., Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara, 1998 May 2002 DEDICATION To my parents, Idalia and José, for encouraging me to be always better. To my family, for their support, love, and for having faith in me. To Alejandro, for his unconditional help, and commitment. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank all the people in the Department of Landscape Architecture for helping me to recognize the sensibility, kindness, and greatness behind a landscape, and the noble tasks that a landscape architect has in shaping them. -

Death and the Invisible Hand: Contemporary Mexican Art, 1988-Present,” in Progress

DEATH AND THE INVISIBLE HAND: CONTEMPORARY MEXICAN ART, 1988-PRESENT by Mónica Rocío Salazar APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ___________________________________________ Charles Hatfield, Co-Chair ___________________________________________ Charissa N. Terranova, Co-Chair ___________________________________________ Mark Rosen ___________________________________________ Shilyh Warren ___________________________________________ Roberto Tejada Copyright 2016 Mónica Salazar All Rights Reserved A mi papá. DEATH AND THE INVISIBLE HAND: CONTEMPORARY MEXICAN ART, 1988-PRESENT by MÓNICA ROCÍO SALAZAR, BS, MA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES – AESTHETIC STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS December 2016 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Research and writing of this dissertation was undertaken with the support of the Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History. I thank Mrs. O’Donnell for her generosity and Dr. Richard Brettell for his kind support. I am especially grateful to Dr. Charles Hatfield and Dr. Charissa Terranova, co- chairs of this dissertation, for their guidance and encouragement. I thank Dr. Mark Rosen, Dr. Shilyh Warren, and Dr. Roberto Tejada for their time and commitment to this project. I also want to thank Dr. Adam Herring for his helpful advice. I am grateful for the advice and stimulating conversations with other UT Dallas professors—Dr. Luis Martín, Dr. Dianne Goode, Dr. Fernando Rodríguez Miaja—as well as enriching discussions with fellow PhD students—Lori Gerard, Debbie Dewitte, Elpida Vouitis, and Mindy MacVay—that benefited this project. I also thank Dr. Shilyh Warren and Dr. Beatriz Balanta for creating the Affective Theory Cluster, which introduced me to affect theory and helped me shape my argument in chapter 4. -

Final-Spanish-Language-Catalog.Pdf

NARRACIÓN TALLADA: LOS HERMANOS CHÁVEZ MORADO 14 de septiembre de 2017 – 3 de junio de 2017 Anne Rowe Página anterior Detalle de La gran tehuana, José Chávez Morado. Foto Lance Gerber, 2016 Esta página Detalle de Tehuana, Tomás Chávez Morado. Foto Lance Gerber, 2016 Índice de contenido Texto, diseño y todas las imágenes © The Annenberg Foundation Trust at Sunnylands 2017 En muchos casos, las imágenes han sido suministradas por los propietarios Los Annenberg y México Embajador David J. Lane página 6 o custodios de la obra. Es posible que las obras de arte individuales que aparecen aquí estén protegidas por derechos de autor en los Estados Unidos Una fuente para Sunnylands páginas 8 – 17 de América o en cualquier otro lugar, y no puedan ser reproducidas de ninguna manera sin el permiso de los titulares de los derechos. El arquitecto Pedro Ramírez Vázquez páginas 18 – 20 Para reproducir las imágenes contenidas en esta publicación, The Annenberg Los hermanos y su obra páginas 21 – 27 Foundation Trust at Sunnylands obtuvo, cuando fue posible, la autorización de los titulares de los derechos. En algunos casos, el Fideicomiso no pudo ubicar al titular de los derechos, a pesar de los esfuerzos de buena fe realizados. El José Chávez Morado páginas 28 – 31 Fideicomiso solicita que cualquier información de contacto referente a tales titulares de los derechos le sea remitida con el fin de contactarlos para futuras Tomás Chávez Morado páginas 32 – 35 ediciones. Publicado por primera vez en 2017 por The Annenberg Foundation Trust at Sunnylands, 37977 Bob Hope Drive, Rancho Mirage, CA 92270, Museo José y Tomás Chávez Morado página 36 Estados Unidos de América. -

The Architecture of the Mexican Revolution

In Search of New Forms The Architecture of the Mexican Revolution Diana Paulina Pérez Palacios* The old Medical Center collapsed in the 1985 earthquake; it was later replaced by the Twentyfirst Century Specialties Center. he culmination of the Mexican Revolution would would promote nationalist values and foster develop- bring with it a program for national construction. ment. This would only be achieved through a program TThe development of this nation, reemerging from for advancing in three priority areas: education, hous- the world’s first twentieth-century revolutionary move- ing, and health. ment, centered on creating a political apparatus that When I say that the nation was just beginning to build itself, I literally mean that the government made *Art critic; [email protected]. a priority of erecting buildings that would not only sup- Photos by Gabriel González (Mercury). ply the services needed to fulfill its political program, 62 but that they would also represent, in and of them- selves, the ideals of the Mexican Revolution. The culmination In the 1920s, after the armed movement ended, of the Mexican Revolution considerable concern existed for the Department of would bring with it a program Health to be forged as a strong institution for society. for national construction. This meant it would undertake great works: the Popo- tla Health Farm; the department’s head offices; and the Tuberculosis Hospital, located in the southern part ects and residential estates such as Satellite City and of Mexico City. In the 1940s and 1950s, more spaces the Pedregal de San Angel area would be built when, for health care were created, such as the Gea González toward the middle of the twentieth century, architects and La Raza Hospitals and the Medical Center. -

Claustro De La Merced: a Re-Evaluation of Mudéjar Style in Colonial Mexico

Claustro de la Merced: A Re-Evaluation of Mudéjar Style in Colonial Mexico Mariana Gómez Fosado The term Mudéjar art or Mudejarismo was coined primarily to a type of wooden ceiling ornamentation known in 1859 by Spanish historian, José Amador de los Ríos. as artesonados, recalling the use of muqarnas and Seljuk Mudéjar art has its origins in the Iberian Peninsula, pres- wooden ceilings in Islamic architecture. ent day Spain and Portugal, a product of the convivencia, Nonetheless, recent scholarship has drawn attention or coexistence of the Abrahamic religions throughout the to the fact that the categorization of these buildings as later medieval period. Scholars describe Mudéjar art as a Mudéjar was primarily based on formal analysis, typical “uniquely Iberian artistic hybrid” in which Islamic motifs of twentieth-century scholarship. According to art histo- were assimilated and incorporated into Christian and Jewish rian María Judith Feliciano, for instance, this has led to works of art.1 Mudéjar art primarily included architecture, an anachronistic analysis of Mudejarismo, as well as as- but was also displayed in ceramics, textiles, and wood sessments that only considered the views of the Spanish carving among others. The most emblematic features of viceroyalty, undervaluing the expression of contemporary Mudéjar are mainly considered in the decoration of archi- ideals of local indigenous populations.4 Scholars also state tectural exteriors and interior spaces, in which bright colors that scholarship is in “need of critical analyses -

Archivo Is a Space Dedicated to Collecting, Exhibiting and Rethinking Design in Its Various Forms

About Archivo Diseño y Arquitectura Archivo is a space dedicated to collecting, exhibiting and rethinking design in its various forms. We are interested in exploring the meaning and potential of design in Mexico, as both a cultural signifier and a source of everyday innovation, with an enormous transformative power. Through a unique research collection open to the public as well as a rich, diverse program of exhibitions and activities, Archivo has estab- lished itself as a pioneering space and a fundamental reference for local architecture and design communities. Founded in 2012 by architect Fernando Romero and his wife Soumaya Slim, Archivo holds a design research collection consisting of over 1,500 design objects that cover a broad spectrum, from everyday objects of Mexican popular culture to limited editions and international design icons of the XXth and XXIst centuries. More than a simple design archive, Archivo functions as an exhibition space, a meeting place, a cultural laboratory, a forum for exchange and debate, and a key element for building knowledge and a critical approach to Mexi- can design. Archivo seeks to reaffirm the importance of design in everyday life, as an area of inquiry that integrates technical, productive, cultural and creative processes. Archivo offers a space for learning and also for critical confrontation, and is a pioneering institution in the field of design and architecture curating and research in Mexico. Archivo also wants to establish itself as a global reference for innovative approaches to the culture and practice of design. Architecture Archivo Collection Archivo is housed in a remarkable mid-century modern house built Archivo houses a design collection of over 1500 objects ranging from by artist and architect Arturo Chávez Paz, neighbouring Luis the first decades of the XXth century to the most recent innovations Barragán's own UNESCO World Heritage house and studio, in the and tendencies in design. -

Mexican Plays with Architecture and Colour

LESZEK MALUGA* MeXiCAn plays WITH ARCHITECTURE AND COLOUR MekSYkAńSkie zabawy ArCHiTekTUrą i koLoreM A b s t r a c t Colour plays a significant role in Mexican culture. Our study deals with four areas of using colour in a spatial composition on an architectural and urban scale. These are murals, i.e. monumental painting in the structure of architectural objects, colour- ful traditional and modern architecture, ornamental forms and structures, and current trends in the revalorisation of historical cities. Keywords: Mexican architecture, spatial composition, colour in architecture Streszczenie W kulturze Meksyku dużą rolę odgrywa kolor. W opracowaniu ukazano cztery ob- szary zastosowania koloru w kompozycji przestrzennej w skali architektonicznej i ur- banistycznej. Są to murale, czyli monumentalne malarstwo w strukturze obiektów architektonicznych, barwna architektura tradycyjna i nowoczesna, formy i struktury dekoracyjne oraz aktualne tendencje w rewaloryzacji miast zabytkowych. Słowa kluczowe: architektura meksykańska, kompozycja przestrzenna, kolor w architekturze * Assoc. Prof. Ph.D. D.Sc. Arch. Leszek Maluga, Department of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture, Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Technology. 123 1. Games with space Constructing is a necessity for some people, for others it is a pleasure – a play with space, material, colour, an intellectual, artistic, aesthetic game. This play, however, should first of all bring pleasure to all those for whom – in the author’s intention – it is created. This ought to involve much greater engagement on the part of the author than a merely dispassionate discharge of professional duties. reversing the order, we must state that if architecture may give pleasure, apart from satisfying basic functional needs, then it should be a sort of a game or play with space. -

Capítulo V Las Nuevas Ideas

CAPÍTULO V LAS NUEVAS IDEAS 316 5.1 La sombra del Movimiento Moderno Tras la caída de los caudillos, el nuevo régimen institucional ve en el modelo racionalista una respuesta a la imagen de progreso y contemporaneidad buscada. El nuevo modelo además -con sus propuestas metodologicas-, es idóneo para atacar necesidades masivas, así el naciente racionalismo encuentra en el Estado mexicano a un gran aliado. El nuevo Estado, con los intelectuales e industriales de su lado, impulsa a la arquitectura racionalista y va a ser en la propia capital -eje de las decisiones-, donde aparecen las primeras manifestaciones de ese nuevo orden; en la periferia hay reticencia y el Tolteca, núm. 1. 1929. Portada. revival tienen continuidad y sólo más adelante se sumaran a la modernidad. La revista Tolteca persigue los mismos fines que su antecesora Cemento aunque prescinde de datos de carácter técnico y no profundiza en sus discursos. Con ello, su radio de difusión es mayor. Aparece en 1929 y muestra en su primer portada1 elementos de carácter futurista, la idea del maquinismo y la fuerza del hombre son conceptos que van ganando adeptos, acorde con las manifestaciones industriales que están apareciendo en esos momentos en México. Destaca en su primer número el llamado Palacio de Policía y Bomberos en la ciudad Edificio para policías y bomberos. capital, realizado por los arquitectos Guillermo Zárraga y 1928. Vicente Mendiola. Fuente: González Gortázar, Fernando. La Vicente Mendiola, edificio de sofisticada geometría arquitectura mexicana del siglo XX, CONACULTA, México, 1994, p. tendiente a la verticalidad. 39. Pero no sólo las grandes construcciones son 1 Tolteca (México D. -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS influence in the construction of the modern TheCarioca School and the Paulista School. architectonic discourse through the exhibi- Comas, guest curator to the exhibition, writes tions Latin American Architecture since 1945 about the similarities and differences of the (1955) and Brazil Builds (1943) setting the two groups of architects and planners that current exhibition at the same level of its pre- shaped Brazil into its modern suit. He intel- decessors, announcing the making of ongoing ligently analyzes them through architectural historiography: “An exhibition and publica- elements and purposes that lets the text tion that function as an ongoing laboratory disseminate and weave both schools inside for constructing new histories” (p. 15). the concepts. Foundation, rule, continuity, Barry Bergdoll’s “Learning from Latin divergence, balance and extension are the America: Public Space, Housing and Land- methods to evolution within the time-frame scape” excels by far the other texts in the of the life span of the modern architects and book. His last exhibition inside the institution their buildings. Latin America in Construction: had to amalgamate his academic DNa with The last individual essay is by Jorge Architecture 1955 - 1980 the precise coordinating skills that require Francisco Liernur, also guest curator, who the heavy machinery of professional research addresses a more contextual piece of writing. Edited by Barry Bergdoll, teams in more than ten countries in Latin He searches for a correlation between Carlos Eduardo Comas, America. It is a grand-finale that sets the bar architecture and new general conditions of Jorge Francisco Liernur, Patricio del Real high in terms of ambition, inventiveness and modernization.