Mexican Plays with Architecture and Colour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modernism Without Modernity: the Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940 Mauro F

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Management Papers Wharton Faculty Research 6-2004 Modernism Without Modernity: The Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940 Mauro F. Guillen University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/mgmt_papers Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, and the Management Sciences and Quantitative Methods Commons Recommended Citation Guillen, M. F. (2004). Modernism Without Modernity: The Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940. Latin American Research Review, 39 (2), 6-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/lar.2004.0032 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/mgmt_papers/279 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modernism Without Modernity: The Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940 Abstract : Why did machine-age modernist architecture diffuse to Latin America so quickly after its rise in Continental Europe during the 1910s and 1920s? Why was it a more successful movement in relatively backward Brazil and Mexico than in more affluent and industrialized Argentina? After reviewing the historical development of architectural modernism in these three countries, several explanations are tested against the comparative evidence. Standards of living, industrialization, sociopolitical upheaval, and the absence of working-class consumerism are found to be limited as explanations. As in Europe, Modernism -

A Cross-Cultural Study of Leisure Among Mexicans in the State of Guerrero, Mexico and Mexican Immigrants from Guerrero in the United States

A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY OF LEISURE AMONG MEXICANS IN THE STATE OF GUERRERO, MEXICO AND MEXICAN IMMIGRANTS FROM GUERRERO IN THE UNITED STATES BY JUAN C. ACEVEDO THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Recreation, Sport & Tourism in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2009 Urbana, Illinois Adviser: Professor Monika Stodolska ABSTRACT The goal of this study was to (a) Examine the existence and the understanding of the concept of leisure among Mexicans from the state of Guerrero, Mexico and among Mexican immigrants from Guerrero, residing in Chicago, IL with specific emphasis on age, gender, and marital status; (b) Identify forces that shape the experience of leisure among Mexicans from the state of Guerrero and among Mexican immigrants from the state of Guerrero, residing in Chicago, IL; and (c) Identify changes in the understanding of the concept and the meaning of leisure, and in leisure behavior among Mexicans from Guerrero caused by immigration to the United States. In order to collect data for this study, 14 interviews with adult residents of Chilpancingo, Guerrero, Mexico and 10 interviews with adult first generation immigrants from Guerrero to Chicago, Illinois were conducted in 2008 and 2009. The findings of the study revealed that the understanding and the meaning of leisure, tiempo libre, among this population was largely similar to the Western notion of leisure, as it was considered to be a subset of time, free from obligations and compulsory activities. Leisure was also considered a state of being where the individual is free to participate in the activity, desires to participate in the activity, and strives to obtain positive outcomes from participation. -

Title: the Avant-Garde in the Architecture and Visual Arts of Post

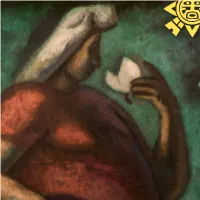

1 Title: The avant-garde in the architecture and visual arts of Post-Revolutionary Mexico Author: Fernando N. Winfield Architecture_media_politics_society. vol. 1, no.3. November 2012 Mexico City / Portrait of an Architect with the City as Background. Painting by Juan O´Gorman (1949). Museum of Modern Art, Mexico. Commenting on an exhibition of contemporary Mexican architecture in Rome in 1957, the polemic and highly influential Italian architectural critic and historian, Bruno Zevi, ridiculed Mexican modernism for combining Pre-Columbian motifs with modern architecture. He referred to it as ‘Mexican Grotesque.’1 Inherent in Zevi’s comments were an attitude towards modern architecture that defined it in primarily material terms; its principle role being one of “spatial and programmatic function.” Despite the weight of this Modernist tendency in the architectural circles of Post-Revolutionary Mexico, we suggest in this paper that Mexican modernism cannot be reduced to such “material” definitions. In the highly charged political context of Mexico in the first half of the twentieth century, modern architecture was perhaps above all else, a tool for propaganda. ARCHITECTURE_MEDIA_POLITICS_SOCIETY Vol. 1, no.3. November 2012 1 2 In this political atmosphere it was undesirable, indeed it was seen as impossible, to separate art, architecture and politics in a way that would be a direct reflection of Modern architecture’s European manifestations. Form was to follow function, but that function was to be communicative as well as spatial and programmatic. One consequence of this “political communicative function” in Mexico was the combination of the “mural tradition” with contemporary architectural design; what Zevi defined as “Mexican Grotesque.” In this paper, we will examine the political context of Post-Revolutionary Mexico and discuss what may be defined as its most iconic building; the Central Library at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico. -

The Casa Cristo Gardens in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2001 Towards Establishing a Process for Preserving Historic Landscapes in Mexico: The aC sa Cristo Gardens in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico Marcela De Obaldia Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Landscape Architecture Commons Recommended Citation De Obaldia, Marcela, "Towards Establishing a Process for Preserving Historic Landscapes in Mexico: The asC a Cristo Gardens in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico" (2001). LSU Master's Theses. 2239. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2239 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOWARDS ESTABLISHING A PROCESS FOR PRESERVING HISTORIC LANDSCAPES IN MEXICO: THE CASA CRISTO GARDENS IN GUADALAJARA, JALISCO, MEXICO. A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Landscape Architecture in The Department of Landscape Architecture by Marcela De Obaldia B.Arch., Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara, 1998 May 2002 DEDICATION To my parents, Idalia and José, for encouraging me to be always better. To my family, for their support, love, and for having faith in me. To Alejandro, for his unconditional help, and commitment. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank all the people in the Department of Landscape Architecture for helping me to recognize the sensibility, kindness, and greatness behind a landscape, and the noble tasks that a landscape architect has in shaping them. -

Many Faces of Mexico. INSTITUTION Resource Center of the Americas, Minneapolis, MN

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 392 686 ( SO 025 807 AUTHOR Ruiz, Octavio Madigan; And Others TITLE Many Faces of Mexico. INSTITUTION Resource Center of the Americas, Minneapolis, MN. REPORT NO ISBN-0-9617743-6-3 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 358p. AVAILABLE FROM ResourceCenter of The Americas, 317 17th Avenue Southeast, Minneapolis, MN 55414-2077 ($49.95; quantity discount up to 30%). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher)(052) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC15 Plus Postage. .DESCRIPTORS Cross Cultural Studies; Foreign Countries; *Latin American Culture; *Latin American History; *Latin Americans; *Mexicans; *Multicultural Education; Social Studies; United States History; Western Civilization IDENTIFIERS *Mexico ABSTRACT This resource book braids together the cultural, political and economic realities which together shape Mexican history. The guiding question for the book is that of: "What do we need to know about Mexico's past in order to understand its present and future?" To address the question, the interdisciplinary resource book addresses key themes including: (1) land and resources;(2) borders and boundaries;(3) migration;(4) basic needs and economic issues;(5) social organization and political participation; (6) popular culture and belief systems; and (7) perspective. The book is divided into five units with lessons for each unit. Units are: (1) "Mexico: Its Place in The Americas"; (2) "Pre-contact to the Spanish Invasion of 1521";(3) "Colonialism to Indeperience 1521-1810";(4) "Mexican/American War to the Revolution: 1810-1920"; and (5) "Revolutionary Mexico through the Present Day." Numerous handouts are include(' with a number of primary and secondary source materials from books and periodicals. -

Death and the Invisible Hand: Contemporary Mexican Art, 1988-Present,” in Progress

DEATH AND THE INVISIBLE HAND: CONTEMPORARY MEXICAN ART, 1988-PRESENT by Mónica Rocío Salazar APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ___________________________________________ Charles Hatfield, Co-Chair ___________________________________________ Charissa N. Terranova, Co-Chair ___________________________________________ Mark Rosen ___________________________________________ Shilyh Warren ___________________________________________ Roberto Tejada Copyright 2016 Mónica Salazar All Rights Reserved A mi papá. DEATH AND THE INVISIBLE HAND: CONTEMPORARY MEXICAN ART, 1988-PRESENT by MÓNICA ROCÍO SALAZAR, BS, MA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES – AESTHETIC STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS December 2016 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Research and writing of this dissertation was undertaken with the support of the Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History. I thank Mrs. O’Donnell for her generosity and Dr. Richard Brettell for his kind support. I am especially grateful to Dr. Charles Hatfield and Dr. Charissa Terranova, co- chairs of this dissertation, for their guidance and encouragement. I thank Dr. Mark Rosen, Dr. Shilyh Warren, and Dr. Roberto Tejada for their time and commitment to this project. I also want to thank Dr. Adam Herring for his helpful advice. I am grateful for the advice and stimulating conversations with other UT Dallas professors—Dr. Luis Martín, Dr. Dianne Goode, Dr. Fernando Rodríguez Miaja—as well as enriching discussions with fellow PhD students—Lori Gerard, Debbie Dewitte, Elpida Vouitis, and Mindy MacVay—that benefited this project. I also thank Dr. Shilyh Warren and Dr. Beatriz Balanta for creating the Affective Theory Cluster, which introduced me to affect theory and helped me shape my argument in chapter 4. -

Final-Spanish-Language-Catalog.Pdf

NARRACIÓN TALLADA: LOS HERMANOS CHÁVEZ MORADO 14 de septiembre de 2017 – 3 de junio de 2017 Anne Rowe Página anterior Detalle de La gran tehuana, José Chávez Morado. Foto Lance Gerber, 2016 Esta página Detalle de Tehuana, Tomás Chávez Morado. Foto Lance Gerber, 2016 Índice de contenido Texto, diseño y todas las imágenes © The Annenberg Foundation Trust at Sunnylands 2017 En muchos casos, las imágenes han sido suministradas por los propietarios Los Annenberg y México Embajador David J. Lane página 6 o custodios de la obra. Es posible que las obras de arte individuales que aparecen aquí estén protegidas por derechos de autor en los Estados Unidos Una fuente para Sunnylands páginas 8 – 17 de América o en cualquier otro lugar, y no puedan ser reproducidas de ninguna manera sin el permiso de los titulares de los derechos. El arquitecto Pedro Ramírez Vázquez páginas 18 – 20 Para reproducir las imágenes contenidas en esta publicación, The Annenberg Los hermanos y su obra páginas 21 – 27 Foundation Trust at Sunnylands obtuvo, cuando fue posible, la autorización de los titulares de los derechos. En algunos casos, el Fideicomiso no pudo ubicar al titular de los derechos, a pesar de los esfuerzos de buena fe realizados. El José Chávez Morado páginas 28 – 31 Fideicomiso solicita que cualquier información de contacto referente a tales titulares de los derechos le sea remitida con el fin de contactarlos para futuras Tomás Chávez Morado páginas 32 – 35 ediciones. Publicado por primera vez en 2017 por The Annenberg Foundation Trust at Sunnylands, 37977 Bob Hope Drive, Rancho Mirage, CA 92270, Museo José y Tomás Chávez Morado página 36 Estados Unidos de América. -

COCKTAILS MARGARITAS BOTTLE BEER the CHINA POBLANO COCKTAIL EXPERIENCE SPARKLING WINE WHITE WINE RED WINE ALCOHOL FREE COFFEE &A

COCKTAILS THE CHINA POBLANO COCKTAIL EXPERIENCE Mexican Mimosa $14 Featuring four of our unique cocktails inspired Cava, fresh fruit juice (daily selection) by Mexico and China $32 per person Colombe $16 Milagro tequila, St. Germain, grapefruit, cinnamon, SPARKLING WINE soda water Perelada, NV Brut Reserva, Spain $48/$12 Mexican Gin & Tonic $17 Gruet, NV Brut Rosé, New Mexico $56/$14 Bombay Sapphire gin, epazote, cilantro, orange peel, Roederer Estate, NV Brut Rosé, California $66 CHINA coriander seeds, Q Tonic Espuma de Piedra, NV Blanc de Blancs, Mexico $78 Oaxacan Old Fashioned $16 Del Maguey Vida mezcal, agave nectar, amaro Montenegro, orange bitters WHITE WINE Pacific Tea $15 Kentia, 2016 Galicia Albariño, Spain $48/$12 Cazadores Reposado tequila, jasmine green tea, Casa Magoni, 2017 Valle de Guadalupe Chardonnay, Chinese 5-spice blend, Negra Modelo beer Mexico $48/$12 Jade Garden $14 Graff, 2014 Mosel Riesling Spatlese, Germany $40/$10 Cilantro-infused Milagro tequila, szechuan peppercorn, lime, makrut Long Meadow Ranch, 2015 Napa Valley Sauvignon Blanc, California $50 La Vida $15 William Fèvre, 2015 Champs Royaux Chablis, France $70 Cazadores Reposado tequila, Bigallet China-China, agave, serrano, spiced hibiscus tea, lavender bitters RED WINE Ma $15 Old Overholt rye whiskey, star anise, ginger, yuzu Beronia, 2015 Rioja Crianza Tempranillo, Spain $48/$12 Mezcal Negroni $16 Honoro Vera, 2016 Calatayud Garnacha, Spain $40/$10 Del Maguey Vida mezcal, Campari, Aperol, Yzaguirre Rojo Ensamble, 2014 Valle de Guadalupe Red Blend, Mexico -

The Architecture of the Mexican Revolution

In Search of New Forms The Architecture of the Mexican Revolution Diana Paulina Pérez Palacios* The old Medical Center collapsed in the 1985 earthquake; it was later replaced by the Twentyfirst Century Specialties Center. he culmination of the Mexican Revolution would would promote nationalist values and foster develop- bring with it a program for national construction. ment. This would only be achieved through a program TThe development of this nation, reemerging from for advancing in three priority areas: education, hous- the world’s first twentieth-century revolutionary move- ing, and health. ment, centered on creating a political apparatus that When I say that the nation was just beginning to build itself, I literally mean that the government made *Art critic; [email protected]. a priority of erecting buildings that would not only sup- Photos by Gabriel González (Mercury). ply the services needed to fulfill its political program, 62 but that they would also represent, in and of them- selves, the ideals of the Mexican Revolution. The culmination In the 1920s, after the armed movement ended, of the Mexican Revolution considerable concern existed for the Department of would bring with it a program Health to be forged as a strong institution for society. for national construction. This meant it would undertake great works: the Popo- tla Health Farm; the department’s head offices; and the Tuberculosis Hospital, located in the southern part ects and residential estates such as Satellite City and of Mexico City. In the 1940s and 1950s, more spaces the Pedregal de San Angel area would be built when, for health care were created, such as the Gea González toward the middle of the twentieth century, architects and La Raza Hospitals and the Medical Center. -

Mexico and M Is for Me!

M is for Mexico and M is for Me! Exploring the similarities and differences shared with the children of Mexico MEXICO ME! Mary Schafer Tooker Avenue School West Babylon, NY M is for Mexico, M is for Me! Exploring the similarities and differences shared with the children of Mexico West Babylon Union Free School District, West Babylon, NY—Tooker Avenue School Designer: Mary Schafer Subjects: Social Studies and English Time frame: 3–4 weeks of 1 ESL unit/day (36 minutes in NY) Grade: 3, 4 English Language Learners Key Concepts NY State Social Studies Standard 3: Geography. Geography can be divided into six essential elements which can be used to analyze important historic, geographic, economic, and environmental questions and issues. These six elements include: the world in spatial terms, places and regions, physical settings, human systems, environment and society, and the use of geography. NY State English Language Arts/English as a Second Language (ESL) Standards 1. Students will read, write, listen, and speak for information and understanding. 2. Students will read, write, listen, and speak for literary response and expression. 5. Students will read, write, listen, and speak for cultural understanding. (ESL) NY State Math, Science, and Technology Standard 2: Students will access, generate, process, and transfer information using appropriate technologies. Schafer – M is for Mexico/Me p. 2 of 2 Understandings: • Students will understand that communities around the world all have distinct characteristics. • Students will understand that even though communities may have different characteristics and values, they can also share similarities. • Students will understand that history shapes current culture. -

Mexico and the People: Revolutionary Printmaking and the Taller De Gráfica Opularp

Schmucker Art Catalogs Schmucker Art Gallery Fall 2020 Mexico and the People: Revolutionary Printmaking and the Taller De Gráfica opularP Carolyn Hauk Gettysburg College Joy Zanghi Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/artcatalogs Part of the Book and Paper Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Latina/o Studies Commons, and the Printmaking Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Recommended Citation Hauk, Carolyn and Zanghi, Joy, "Mexico and the People: Revolutionary Printmaking and the Taller De Gráfica opularP " (2020). Schmucker Art Catalogs. 35. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/artcatalogs/35 This open access art catalog is brought to you by The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The Cupola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mexico and the People: Revolutionary Printmaking and the Taller De Gráfica Popular Description During its most turbulent and formative years of the twentieth century, Mexico witnessed decades of political frustration, a major revolution, and two World Wars. By the late 1900s, it emerged as a modernized nation, thrust into an ever-growing global sphere. The revolutionary voices of Mexico’s people that echoed through time took root in the arts and emerged as a collective force to bring about a new self- awareness and change for their nation. Mexico’s most distinguished artists set out to challenge an overpowered government, propagate social-political advancement, and reimagine a stronger, unified national identity. Following in the footsteps of political printmaker José Guadalupe Posada and the work of the Stridentist Movement, artists Leopoldo Méndez and Pablo O’Higgins were among the founders who established two major art collectives in the 1930s: Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios (LEAR) and El Taller de Gráfica opularP (TGP). -

Mexico's American/America's Mexican: Cross- Border Flows of Nationalism and Culture Between the United States and Mexico Brian D

History Publications History 2013 Mexico's American/America's Mexican: Cross- border Flows of Nationalism and Culture between the United States and Mexico Brian D. Behnken Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/history_pubs Part of the Cultural History Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Latin American History Commons, and the United States History Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ history_pubs/99. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mexico's American/America's Mexican: Cross-border Flows of Nationalism and Culture between the United States and Mexico Abstract In 2006, immigrant rights protests hit almost every major city in the United States. Propelled by a wave of anti-immigrant sentiment and proposed immigration legislation that developed out of the 2004 presidential election, Latino/a activists demanded an end to the biased, and often racist, immigration reform debate, a debate that characterized immigrants as violent criminals who wantonly broke American law. Individuals of all ethnicities and nationalities, but mainly Latinos, participated in massive demonstrations to oppose the legislation and debate. In the Southwest, in cities such as Los Angeles, Phoenix, Dallas, and El Paso, Mexican Americans showed by force of numbers that they opposed this debate.