The Representation of Blackness in Megamind Character of Tom Mcgrath’S Megamind Diannita Rachmawati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shrek4 Manual.Pdf

Important Health Warning About Playing Video Games Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including fl ashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents should watch for or ask their children about the above symptoms— children and teenagers are more likely than adults to experience these seizures. The risk of photosensitive epileptic seizures may be reduced by taking the following precautions: Sit farther from the screen; use a smaller screen; play in a well-lit room; and do not play when you are drowsy or fatigued. If you or any of your relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. ESRB Game Ratings The Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) ratings are designed to provide consumers, especially parents, with concise, impartial guidance about the age- appropriateness and content of computer and video games. This information can help consumers make informed purchase decisions about which games they deem suitable for their children and families. -

SHREK the MUSICAL Official Broadway Study Guide CONTENTS

WRITTEN BY MARK PALMER DIRECTOR OF LEARNING, CREATIVE AND MEDIA WIldERN SCHOOL, SOUTHAMPTON WITH AddITIONAL MATERIAL BY MICHAEL NAYLOR AND SUE MACCIA FROM SHREK THE MUSICAL OFFICIAL BROADWAY STUDY GUIDE CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 Welcome to the SHREK THE MUSICAL Education Pack! A SHREK CHRONOLOGY 4 A timeline of the development of Shrek from book to film to musical. SynoPsis 5 A summary of the events of SHREK THE MUSICAL. Production 6 Interviews with members of the creative team of SHREK THE MUSICAL. Fairy Tales 8 An opportunity for students to explore the genre of Fairy Tales. Feelings 9 Exploring some of the hang-ups of characters in SHREK THE MUSICAL. let your Freak flag fly 10 Opportunities for students to consider the themes and characters in SHREK THE MUSICAL. One-UPmanshiP 11 Activities that explore the idea of exaggerated claims and counter-claims. PoWer 12 Activities that encourage students to be able to argue both sides of a controversial topic. CamPaign 13 Exploring the concept of campaigning and the elements that make a campaign successful. Categories 14 Activities that explore the segregation of different groups of people. Difference 15 Exploring and celebrating differences in the classroom. Protest 16 Looking at historical protesters and the way that they made their voices heard. AccePtance 17 Learning to accept ourselves and each other as we are. FURTHER INFORMATION 18 Books, CD’s, DVD’s and web links to help in your teaching of SHREK THE MUSICAL. ResourceS 19 Photocopiable resources repeated here. INTRODUCTION Welcome to the Education Pack for SHREK THE MUSICAL! Increasingly movies are inspiring West End and Broadway shows, and the Shrek series, based on the William Steig book, already has four feature films, two Christmas specials, a Halloween special and 4D special, in theme parks around the world under its belt. -

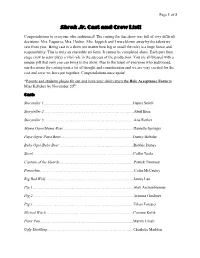

Shrek Jr. Cast and Crew List!

Page 1 of 3 Shrek Jr. Cast and Crew List! Congratulations to everyone who auditioned! The casting for this show was full of very difficult decisions. Mrs. Esquerra, Mrs. Hosker, Mrs. Joppich and I were blown away by the talent we saw from you. Being cast in a show (no matter how big or small the role) is a huge honor and responsibility. This is truly an ensemble art form. It cannot be completed alone. Each part from stage crew to actor plays a vital role in the success of the production. You are all blessed with a unique gift that only you can bring to the show. Due to the talent of everyone who auditioned, our decisions for casting took a lot of thought and consideration and we are very excited for the cast and crew we have put together. Congratulations once again! *Parents and students please fill out and have your child return the Role Acceptance Form to Miss Kelleher by November 20th. Cast: Storyteller 1……………………………………………………….…..Hanna Smith Storyteller 2………………………………………………………...….Abril Brea Storyteller 3……………………………..……………………..………Ana Rother Mama Ogre/Mama Bear………………………….………………...…Danielle Springer Papa Ogre/ Papa Bear……………………………………………..…Danny Boboltz Baby Ogre/Baby Bear ………………………………...…….………...Robbie Dubay Shrek…………………………………………………………….....….Collin Toole Captain of the Guards………………………………………….…...…Patrick Twomey Pinocchio……………………………………………………………....Colin McCauley Big Bad Wolf………………………………………………….….…....James Lau Pig 1……………………………………………………………….......Alex Aschenbrenner Pig 2…………………………………………………………….…......Arianna Gardiner Pig 3………………………………………………………….......……Ethan -

In March, 2002 the Dreamworks

TM The animated feature and the making of by Kate McCallum n March, 2002 the DreamWorks ani- freed from the stress of New York life. mated films as Space Jam and Cool World. mated feature Shrek broke ground by When those plotting penguins sabotage His television work includes directing on I receiving the first official Oscar® for the ship, Alex, Marty, Melman and Gloria The Ren & Stimpy Show, as well as other the newly created Best Animated Feature find themselves washed ashore on the exotic projects for Nickelodeon. Adding their tal- Film category. Now, from DreamWorks island of Madagascar. Now these native New ents to the film were writers Mark Burton Animation SKG comes the new, com- Yorkers have to figure out how to survive in and Billy Frolick. Burton is a U.K.-based puter-animated comedy Madagascar. the wild and discover the true meaning of comedy writer with a varied TV and film Alex the Lion (voiced by Ben Stiller) is the phrase “It’s a jungle out there.” career on both sides of the Atlantic. He has the king of the urban jungle as the main Madagascar was directed by Eric Darnell written extensively for many British comedy attraction at New York’s Central Park Zoo. and Tom McGrath, who are also two of shows, including Clive Anderson Talks Back, He and his best friends Marty the Zebra the writers on this film. Darnell joined Jack Dee’s Happy Hour, Never Mind The (Chris Rock), Melman the Giraffe (David PDI’s (now PDI/DreamWorks Animation) Buzzcocks, 2DTV, Have I Got News For You Schwimmer) and Gloria the Hippo (Jada Character Animation Group in 1991 and and Spitting Image. -

ALPHABETICAL LIST of Dvds and Vts 9/6/2011 DVD a Mighty Heart

ALPHABETICAL LIST OF DVDs AND VTs 9/6/2011 DVD A Mighty Heart: Story of Daniel Pearl A Nurse I am – Documentary and educational film about nurses A Single Man –with Colin Firth and Julianne Moore (R) Abe and the Amazing Promise: a lesson in Patience (VeggieTales) Akeelah and the Bee August Rush - with Freddie Highmore, Keri Russell, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Terrence Howard, Robin Williams Australia - with Hugh Jackman, Nicole Kidman Aviator (story of Howard Hughes - with Leonardo DiCaprio Because of Winn-Dixie Beethoven - with Charles Grodin, Bonnie Hunt Big Red Black Beauty Cats & Dogs Changeling - with Angelina Jolie Charlie and the Chocolate Factory - with Johnny Depp Charlie Wilson’s War - with Tom Hanks, Julie Roerts, Phil Seymour Hoffman Charlotte’s Web Chicago Chocolat - with Juliette Binoche, Judi Dench, Alfred Molina, Lena Olin & Johnny Depp Christmas Blessing - with Neal Patrick Harris Close Encounters of the Third Kind – with Richard Dreyfuss Date Night – with Steve Carell and Tina Fey (PG-13) Dear John – with Channing Tatum and Amanda Seyfried (PG-13) Doctor Zhivago Dune Duplicity - with Julia Roberts and Clive Owen Enchanted Evita Finding Nemo Finding Neverland Fireproof – with Kirk Cameron on Erin Bethea (PG) Five People You Meet in Heaven Fluke Girl With a Pearl Earring – with Colin Firth, Scarlett Johannson, Tom Wilkinson Grand Torino (with Clint Eastwood) Green Zone – with Matt Damon (R) Happy Feet Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Hildalgo with Viggo Mortensen (PG13) Holiday, The – with Cameron Diaz, Kate Winslet, -

Theaters 3 & 4 the Grand Lodge on Peak 7

The Grand Lodge on Peak 7 Theaters 3 & 4 NOTE: 3D option is only available in theater 3 Note: Theater reservations are for 2 hours 45 minutes. Movie durations highlighted in Orange are 2 hours 20 minutes or more. Note: Movies with durations highlighted in red are only viewable during the 9PM start time, due to their excess length Title: Genre: Rating: Lead Actor: Director: Year: Type: Duration: (Mins.) The Avengers: Age of Ultron 3D Action PG-13 Robert Downey Jr. Joss Whedon 2015 3D 141 Born to be Wild 3D Family G Morgan Freeman David Lickley 2011 3D 40 Captain America : The Winter Soldier 3D Action PG-13 Chris Evans Anthony Russo/ Jay Russo 2014 3D 136 The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader 3D Adventure PG Georgie Henley Michael Apted 2010 3D 113 Cirque Du Soleil: Worlds Away 3D Fantasy PG Erica Linz Andrew Adamson 2012 3D 91 Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2 3D Animation PG Ana Faris Cody Cameron 2013 3D 95 Despicable Me 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2010 3D 95 Despicable Me 2 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2013 3D 98 Finding Nemo 3D Animation G Ellen DeGeneres Andrew Stanton 2003 3D 100 Gravity 3D Drama PG-13 Sandra Bullock Alfonso Cuaron 2013 3D 91 Hercules 3D Action PG-13 Dwayne Johnson Brett Ratner 2014 3D 97 Hotel Transylvania Animation PG Adam Sandler Genndy Tartakovsky 2012 3D 91 Ice Age: Continetal Drift 3D Animation PG Ray Romano Steve Martino 2012 3D 88 I, Frankenstein 3D Action PG-13 Aaron Eckhart Stuart Beattie 2014 3D 92 Imax Under the Sea 3D Documentary G Jim Carrey Howard Hall -

Madagascar: a Crate Adventure Opens at Universal Studios Singapore® on 16 May 2011

p r e s s r e l e a s e Madagascar: A Crate Adventure Opens at Universal Studios Singapore® on 16 May 2011 SINGAPORE – 09 MAY 2011 – Universal Studios Singapore, the world-class theme park within Resorts World Sentosa, the first integrated resort destination in Singapore, today announced that guests can soon join the famous escapees from the New York Zoo when Madagascar: A Crate Adventure debuts on 16 May. This new theme park attraction is inspired by DreamWorks Animation SKG, Inc.’s (Nasdaq: DWA) Madagascar film series, one of the most successful animated movie franchises of all time. Among the longest rides in Universal Studios Singapore, Madagascar: A Crate Adventure is a nine-minute indoor flume ride that takes guests on a river boat adventure with Alex the Lion, Marty the Zebra, Melman the Giraffe and Gloria the Hippo. The Central Park “Zoosters” join forces with the eccentric leader of the local lemurs, King Julien – and Universal Studios Singapore guests – to help defeat the dreaded Foosa. Aided by the technically-savvy and hilarious Penguins, the heroes and guests together defeat the Foosa at the rim of a bubbling volcanic cauldron. Along the way, they encounter a giant alligator, wild- eyed spiders and more. Mr. Jeffrey Katzenberg, Chief Executive Officer of DreamWorks Animation, said: “Madagascar: A Crate Adventure is the primary attraction built within the first-ever theme park zone dedicated exclusively to all things related to and inspired by our Madagascar movie series. We are excited about the way in which it allows people to interact with DreamWorks Animation’s unique characters and worlds in a memorable family experience.” Mr. -

2007 Annual Report

2007 Annual Report As a celebration of the creative spirit that drives everything we do at DreamWorks Animation, we held an artwork contest in 2007 in which we invited all employees to submit a design to be featured in the Annual Report. Every submission celebrated the unique and fulfilling process of working on an animated film at the Company. Rhion Magee, Consumer Products, created the winning submission. Dear Fellow Shareholders, I am pleased to report that 2007 was our most successful year since we took DreamWorks Animation public in 2004, thanks in large part to the blockbuster success of Shrek the Third and the Shrek franchise as a whole. In addition to boasting the best domestic opening in the history of animated film, Shrek the Third became the second highest grossing film of 2007 in the U.S. and the fourth best performing animated movie of all time. Even in a challenging home video market, Shrek the Third has risen above the competition and performed well. In 2007, we advanced our mission to successfully expand the Shrek brand with Shrek the Halls, our first made-for-television special. Over 21 million people throughout the U.S. watched the program this past holiday season on ABC. Additionally, Shrek made his first appearance at the annual Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade as the official 2007 Ambassador for the event. In December, we will take our brand expansion one step further by bringing Shrek the Musical to the Broadway Theatre in New York City. We are very excited about this tremendous opportunity to further extend one of the most successful franchises in Hollywood history. -

Irradiance Caching at Dreamworks

Global Illumination Across Industries Ray Tracing vs. Point-Based GI for Animated Films Eric Tabellion [email protected] Introduction • Global Illumination (GI) usage at DreamWorks Animation – Bounce lighting – Ambient occlusion – HDR Environment map lighting (IBL) – Used on many films since “Shrek 2” • Used in a variety of shots • Various characters, props and environments • Global Illumination system – Using Ray Tracing and Irradiance Caching (IC) • [Tabellion and Lamorlette 2004] • [Krivanek et al. 2008] – Using point-based GI • [Christensen 2008] Direct Lighting Only Direct + Indirect Lighting Example: “How To Train Your Dragon ” Example: “How To Train Your Dragon ” Example: “Shrek Forever After” GI in Animated Film Production • Requirements: – High Quality • No noise, buzzing or popping – Artistic control • Offer physically correct starting point • Let the user tweak shaders further – Good shader integration – Speedy interaction • Add bounce cards to control lighting • Apply localized filters to GI – Scene complexity • Scene complexity is unbounded (more or less tuned) GI in Animated Film Production • Multi-department Impact: – Modelling & Animation • Geometry with bad contact / penetrations – Surfacing • Account for GI as a lighting scenario • Define bouncing characteristics – FX • Effects do illuminate and occlude – Lighting • GI not always intuitive – Light is coming from everywhere • GI produces simpler lighting rigs • Propagates well to other shots / sequences Ray-Tracing-Based GI System Overview • Micropolygon Deep Frame Buffer Renderer -

HP Converged Infrastructure Solutions Help Dreamworks Animation

HP Converged Infrastructure solutions help DreamWorks Animation create great films and blaze a path toward Instant-On Studio turns to HP technology to deliver more than 60 percent greater throughput and help break new ground faster than ever. “DreamWorks utilize about 5 percent of its rendering capacity from the cloud. In 2011, we intend to move more than 50 percent of our rendering capacity into the cloud.” Ed Leonard, CTO, DreamWorks Animation SKG Objective Popcorn, please Boost rendering throughput while minimizing It is one of life’s most universal pleasures: enter a power consumption and streamlining data center movie theatre, sit back in a comfortable chair, watch a requirements screen, and be swept away. DreamWorks Animation SKG delivered this an Approach unprecedented three times in 2010. Out of tens of Onsite testing showed that HP server blades, thousands of titles released in over 100 years of storage, networking, and cloud services would cinema, two DreamWorks Animation movies (Shrek boost efficiency and defer power capacity 2 and Shrek the Third) are among the top 25 all-time upgrade. highest-grossing films.* There are plans at DreamWorks Animation IT improvements to set more records—and the studio • More than 60% greater rendering throughput needs more acceleration from • More than 30% higher performance per watt technology. • Minimized server administration through remote “We hire people who have management unbounded imaginations,” • Service-level agreements in backup and archiving explains Ed Leonard, met or exceeded CTO, -

Antz Bee Movie El Dorado Flushed Away Kung Fu Panda How to Train Your Dragon Madagascar Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa Monsters Vs

YOU ARE CORDIALLY INVITED TO THE OPENING RECEPTION FOR an exhibition of visual development and production artwork from DreamWorks DreamWorlds Animation’s feature films. PLEASE JOIN DREAMWORKS ANIMATION ARTISTS AND EXECUTIVES, ART CENTER PRESIDENT LORNE BUCHMAN, ART CENTER TRUSTEE ALYCE WILLIAMSON, ILLUSTRATION DEPARTMENT CHAIR ANN FIELD AND WILLIAMSON GALLERY DIRECTOR STEPHEN NOWLIN FOR THE OPENING OF DreamWorlds, a behind-the-scenes look at the artistry and imagination of animated filmmaking. THURSDAY, MARCH 4, 2010 7–8 PM PANEL DISCUSSION Ahmanson Auditorium 8–9 PM WILLIAMSON GALLERY RECEPTION Panel Discussion: Kathy Altieri DreamWorks Production Designer for the soon-to-be-released How to Train Your Dragon (March 26, 2010), Art Center alumna, ILLU ’81 Kendal Cronkhite DreamWorks Production Designer, Madagascar films, Art Center alumnus, ILLU ’87 Sam Michlap DreamWorks Visual Development Artist and DreamWorlds co-curator Alyce de Roulet Williamson Gallery Art Center College of Design | 1700 Lida Street | Pasadena, CA 91103 (Once on campus, please follow the signs for parking information.) featuring artwork from: ANTZ BEE MOVIE EL DORADO FLUSHED AWAY KUNG FU PANDA HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON MADAGASCAR MADAGASCAR: ESCAPE 2 AFRICA MONSTERS VS. ALIENS OVER THE HEDGE PRINCE OF EGYPT SHARK TALE SHREK SHREK 2 SHREK THE THIRD SINBAD SPIRIT: STALLION OF THE CIMARRON EXHIBITION DATES: MARCH 5 – MAY 9, 2010 DreamWorlds has been made possible through the support of DreamWorks Animation, Williamson Gallery Patrons and the Pasadena Art Alliance. Art Center extends a special thanks to all DreamWorks staff who have contributed to the exhibition’s development — in particular Angela Lepito, Sam Michlap, Brian Smith and Beverly Herman, without whose expertise, patience and commitment this project would never have been realized.. -

Hi Guess the Movie 2016 Answers

33. Argo 75. The Dark Knight 117. Mary Poppins 34. Resident Evil 76. The Matrix 118. Scoob Doo* 35. Up 77. Wall-E 119. Tarzan 36. The Smurfs 78. Amelie 120. Top Gun 37. Gladiator 79. Sin City 121. Tron Hi Guess The Movie 2016 38. Taken 80. The Incredibles 122. Blood Diamond Answers 39. Aladdin 81. Les Miserables 123. Yogi Bear - Man Zhang 40. Ghost Rider 82. Machete 124. The Help 41. G.I. Joe 83. Psycho 125. Spirited Away Main Game 42. Blade 84. Kill Bill 126. Puss in Boots 1. Cars 43. Madagascar 85. Mega Mind 127. Hulk 2. Iron Man 44. The Hobbit 86. Wreck It Ralph 128. The Shining 3. King Kong 45. X-Men 87. Shutter Island 129. The Deer Hunter 4. E.T. 46. Toy Story 88. Green Lantern 130. The Dictator 5. The Godfather 47. Braveheart 89. Hell Boy 131. The Graduate 6. Fury 48. The Simpsons 90. Rocky 132. The Karate Kid 7. Harry Potter 49. Troy 91. Jaws 133. The Sixth Sense 8. The Lion King 50. Tomb Raider 92. Casper 134. The Wolverine 9. Spider-Man 51. The Iron Lady 93. Borat 135. The Great Escape 10. Ice Age 52. Bambi 94. Bruce Almighty 136. The Mask of Zorro 11. Transformers 53. Austen Powers 95. Tangled 137. The Pianist 12. Planes 54. Cinderella 96. Fantastic Four 138. The Terminal 13. Scream 55. Jurassic Park 97. The Green Mile 139. Flight 14. Brave 56. Star Wars 98. V for Vendetta 140. Identity 15. Ted 57. Spongebob 99. Snow White 141.