New Acquisitions 2008 African-American Masters Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bob Dylan: the 30 Th Anniversary Concert Celebration” Returning to PBS on THIRTEEN’S Great Performances in March

Press Contact: Harry Forbes, WNET 212-560-8027 or [email protected] Press materials; http://pressroom.pbs.org/ or http://www.thirteen.org/13pressroom/ Website: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/gperf/ Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/GreatPerformances Twitter: @GPerfPBS “Bob Dylan: The 30 th Anniversary Concert Celebration” Returning to PBS on THIRTEEN’s Great Performances in March A veritable Who’s Who of the music scene includes Eric Clapton, Stevie Wonder, Neil Young, Kris Kristofferson, Tom Petty, Tracy Chapman, George Harrison and others Great Performances presents a special encore of highlights from 1992’s star-studded concert tribute to the American pop music icon at New York City’s Madison Square Garden in Bob Dylan: The 30 th Anniversary Concert Celebration in March on PBS (check local listings). (In New York, THIRTEEN will air the concert on Friday, March 7 at 9 p.m.) Selling out 18,200 seats in a frantic, record-breaking 70 minutes, the concert gathered an amazing Who’s Who of performers to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the enigmatic singer- songwriter’s groundbreaking debut album from 1962, Bob Dylan . Taking viewers from front row center to back stage, the special captures all the excitement of this historic, once-in-a-lifetime concert as many of the greatest names in popular music—including The Band , Mary Chapin Carpenter , Roseanne Cash , Eric Clapton , Shawn Colvin , George Harrison , Richie Havens , Roger McGuinn , John Mellencamp , Tom Petty , Stevie Wonder , Eddie Vedder , Ron Wood , Neil Young , and more—pay homage to Dylan and the songs that made him a legend. -

CBA PTV Promo 1104

Respect #11 Format ADDITIONAL GIFT Personalized letter and form. Ms. Sample, please keep this as a NJN Special Gift Reply Form record of your extra gift. YES, I respect NJN’s unique commitment to television excellence and programming ➧ that reflects my interests and standards. Here’s my special contribution to prove it. ( ) $00 ( ) $000 ( ) Other $_____ The larger your gift, the ■ My check to NJN is enclosed. stronger we’ll be to face Charge my ■ ■ MC AMEX ■ VISA ■ Discover a future with increased Honored Member programming costs. Thank you. Account No. ______________________________ Ms. Jane A. Sample Exp. Date _______/___ Please correct name and address. Director of Membership Optional: Ms. Jane A. Sample My e-mail address is My gift amount ______________ Date sent ______________ 500 Elm Street ____________________. Yourtown, ST 12345 THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT! NJN, P.O. Box 777, Trenton, NJ 08625-0777 RESPECT. Linda Epps Director of Development Dear Ms. Sample: Respect is something we take very seriously here at NJN, especially when it comes to you and our other supporters. Respect for your intelligence, interests and valuable time is our number one priority when we make our programming decisions. We continue to broadcast all the NJN programs that you’ve come to rely on, programs that have demonstrated for many years our respect for your intelligence and taste. You can count on NJN as a vital source of information, ideas and points of view. We provide insights, not sound bites, so you can gain perspective on issues that affect you. Our programs promote understanding and civic participation -- and bring you exclusive “live” performances that can inspire and delight you. -

June Program Guide

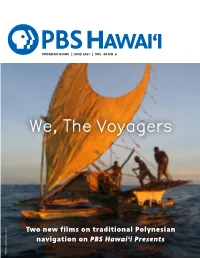

PROGRAM GUIDE | JUNE 2021 | VOL. 40 NO. 6 Two new films on traditional Polynesian navigation on PBS Hawai‘i Presents Wade Fairley, copyright Vaka Taumako Project Taumako copyright Vaka Fairley, Wade A Long Story That Informed, Influenced STATEWIDE BOARD OF DIRECTORS and Inspired Chair The show’s eloquent description Joanne Lo Grimes nearly says it all… Vice Chair Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox Jason Haruki features engaging conversations with Secretary some of the most intriguing people in Joy Miura Koerte Hawai‘i and across the world. Guests Treasurer share personal stories, experiences Kent Tsukamoto and values that have helped shape who they are. Muriel Anderson What it does not express is the As we continue to tell stories of Susan Bendon magical presence Leslie brought to Hawai‘i’s rich history, our content Jodi Endo Chai will mirror and reflect our diverse James E. Duffy Jr. each conversation and the priceless communities, past, present and Matthew Emerson collection of diverse voices and Jason Fujimoto untold stories she captured over the future. We are in the process of AJ Halagao years. Former guest Hoala Greevy, redefining some of our current Ian Kitajima Founder and CEO of Paubox, Inc., programs like Nā Mele: Traditions in Noelani Kalipi may have said it best, “Leslie was Hawaiian Song and INSIGHTS ON PBS Kamani Kuala‘au HAWAI‘I, and soon we will announce Theresia McMurdo brilliant to bring all of these pieces Bettina Mehnert of Hawai‘i history together to live the name and concept of a new series. Ryan Kaipo Nobriga forever in one amazing library. -

FINAL Production Bios American Masters James Beard

Press Contact: Donna Williams, WNET, 212.560.8030, [email protected] Press Materials: http://pbs.org/pressroom or http://thirteen.org/pressroom Websites: http://pbs.org/americanmasters, http://facebook.com/americanmasters, @PBSAmerMasters , http://pbsamericanmasters.tumblr.com, http://youtube.com/AmericanMastersPBS , http://instagram.com/pbsamericanmasters , #AmericanMastersPBS American Masters – James Beard: America’s First Foodie Premieres nationwide Friday, May 19, 9-10 p.m. on PBS (check local listings) Production Bios Beth Federici Producer and Director , American Masters – James Beard: America’s First Foodie Beth Federici is an award-winning documentary filmmaker and television producer. Most recently, she co-directed and produced the feature documentary Space, Land and Time: Underground Adventures with Ant Farm , for which she was awarded the 2010 Cine Golden Eagle Award. Her credits also include the documentary Neither Here Nor There (co- director/producer/editor), which was awarded the Best of the Heartland award at the Kansas City Film Festival and was broadcast on Missouri PBS; and the award-winning concert film Bauhaus Gotham . In addition to her work as a filmmaker, Federici is also a dedicated media educator, teaching media literacy theory and media production skills to students all over the country. She currently works as an independent producer, editor and educator in Portland, Oregon. Kathleen Squires Co- Producer , American Masters – James Beard: America’s First Foodie Kathleen’s 25-year career has spanned book, blog, newsprint and glossy, with hundreds of published works ranging from restaurant reviews to travel features to award-winning cookbooks. Kathleen’s work appears in The Wall Street Journal , Details , Saveur , Cooking Light , Fodors.com , Zagat.com , National Geographic Traveler , The New York Daily News , The New York Post and Time Out New York , among many other publications. -

Master of Arts in American Studies

A Message from the Director of the M.A. in American Studies 29 A Message from the Director The graduate program in American Studies at Fairfield University is an interdisci- plinary course of study drawing upon the expertise of full-time faculty members . They represent nine departments and programs including Black Studies, English, History, Philosophy, Politics, Sociology, Religious Studies, Women’s Studies, and Visual and Performing Arts . The American Studies program focuses on the cultural and intellectual life of the United States and is dedicated to providing a compre- hensive and critical understanding of the American experience . Students design a curriculum to meet their specific needs in consultation with an MASTER OF ARTS academic advisor . They may focus on a traditional discipline or explore a par- ticular topic . America is a culture of cultures, and our offerings are inclusive and IN respectful of the enormous diversity in the American people and their experience . To undertake the formidable task of developing a better understanding and appre- ciation of the complexities in the American experience, we employ the consider- AMERICAN STUDIES able resources of our University community while also encouraging students to avail themselves of the resources in the surrounding New York metropolitan region . In response to the personal and professional time constraints of our student population, classes normally take place in the late afternoon, evening, and occasionally on weekends . To facilitate a supportive mentor-learning environ- ment, all courses are offered in a seminar format . The graduate students in our program include professionals seek- ing intellectual and cultural enrichment, educators enhancing their professional development, full-time parents pre- paring to re-enter the marketplace, and others planning to pursue further professional studies or academic degrees . -

KCET, Los Angeles Membership Renewal Campaign Kcetr020

KCET, Los Angeles Membership Renewal Campaign KCETr020 GOALS: Pledge Rate: 16% Average Gift: $68 Credit Card Rate: 40% CONTACT INFORMATION: KCET 2900 West Alameda Ave. Burbank, CA 91505-4267 (747) 201-5238 [email protected] CAMPAIGN NOTES: During this campaign, you will be calling members in their renewal cycle and inviting them to renew their membership support for KCET. ABOUT KCET: On-air, online, and in the community, KCET plays a vital role in the cultural and educational enrichment of Southern and Central California. In addition to broadcasting the finest programs from around the world, KCET produces and distributes award-winning local programs that explore the people, places and topics that are relevant to our region. Whether it is through our broadcast, via cable, over digital platforms and devices, or from our extensive community outreach and education programs, KCET consistently delivers inspiring global content that informs, educates and enlightens millions of individuals in Southern and Central California. KCET is a content channel of the Public Media Group of Southern California, formed by the 2018 merger of KCETLink and PBS SoCal. BROADCAST AREA Nearly two million viewers watch KCET in the average month in 11 Counties across Southern California: from as far north as San Luis Obispo, as far south to San Diego and as far east to the Nevada / Arizona border. CALIFORNIA PBS STATIONS AT-HOME LEARNING COVID-19 RAPID RESPONSE INITIATIVE As leaders in learning and as community partners, California’s PBS stations are here to help our state navigate this uncharted journey of At-Home Learning with you. -

A Finding Aid to the Charles Henry Alston Papers, 1924-1980, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Charles Henry Alston Papers, 1924-1980, in the Archives of American Art Jayna M. Hanson Funding for the digitization of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art August 2008 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Biographical Information, 1924-1977........................................................ 5 Series 2: Correspondence, 1931-1977.................................................................... 6 Series 3: Commission and Teaching Files, 1947-1976........................................... -

Extra Credit

Artist: Charles Alston Title: Family No. 1 Date of Work:1955 Dimensions 21 3⁄4 x 16 1⁄4 in. / 55.2 x 41.3 cm Charles Alston (1907 - 77), painter, sculptor, muralist and teacher of art, was born in North Carolina. This important artist has had a brilliant career studded with prizes and recognition of his varied talents. He received his Bachelor of Arts and Master of Arts degrees from Columbia University where he held a Dow Fellowship in 1931 and was Rosenwald Fellow in Painting (1939 - 41). He did further graduate work at New York University and studied art at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and the New York art Students League, where he has been an instructor since 1950. He was an Associate Professor of Art at the University of the City of New York. Alston has exhibited in the principal museums of the US and many of them count his works in their permanent collections, as do a number of important art collectors. His murals may be found in such institutions as the Museum of National History in NY, Harlem Hospital in LA, The City College of New York and Abraham Lincoln High School in Brooklyn. His work encompasses many styles, from pure abstraction to almost pure realism. In the latter form, we may note the influence of African sculpture. His work is always strong and highly individualistic; warm with rich color, sharp in blacks and clear whites, or soft and compassionate in texture and color. It is, in fact, so varied that it cannot be categorized, but it is always masterly. -

African American Art Holbrook Lauren South Dakota State University

The Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 6 Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume Article 3 6: 2008 2008 Documented Struggles and Triumph: African American Art Holbrook Lauren South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/jur Part of the African American Studies Commons, Art and Design Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Lauren, Holbrook (2008) "Documented Struggles and Triumph: African American Art," The Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 6, Article 3. Available at: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/jur/vol6/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in The ourJ nal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GS019 JUR08_GS JUR text 11/18/09 8:53 AM Page 7 DOCUMENTED STRUGGLES AND TRIUMPH: AFRICAN AMERICAN ART 7 Documented Struggles and Triumph: African American Art (winner of a 2008 SDSU Schultz-Werth Award) Author: Holbrook Lauren Faculty Sponsor: Dr. Leda Cempellin Department: Visual Arts “I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. -

MFA Boston, Acquisition of Works from Axelrod Collection, Press Release, P

MFA Boston, Acquisition of Works from Axelrod Collection, Press Release, p. 1 Contact: Karen Frascona 617.369.3442 [email protected] MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON, ACQUIRES WORKS BY AFRICAN AMERICAN ARTISTS FROM JOHN AXELROD COLLECTION MFA Marks One-Year Anniversary of Art of the Americas Wing with Display including Works by John Biggers, Eldzier Cortor, and Archibald Motley Jr. BOSTON, MA (November 3, 2011)—Sixty-seven works by African American artists have recently been acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), from collector John Axelrod, an MFA Honorary Overseer and long-time supporter of the Museum. The purchase has enhanced the MFA’s American holdings, transforming it into one of the leading repositories for paintings and sculpture by African American artists. The Museum’s collection will now include works by almost every major African American artist working during the past century and a half. Seven of the works are now displayed in the Art of the Cocktails, about 1926, Archibald Motley Americas Wing, in time for its one-year anniversary this month. This acquisition furthers the Museum’s commitment to showcasing the great multicultural artistry found throughout the Americas. It was made possible with the support of Axelrod and the MFA’s Frank B. Bemis Fund and Charles H. Bayley Fund. Axelrod has also donated his extensive research library of books about African American artists to the Museum, as well as funds to support scholarship. ―This is a proud moment for the MFA. When we opened the Art of the Americas Wing last year, our goal was to reflect the diverse interests and backgrounds of all of our visitors. -

KCET Curriculum-Related Programming 3/16/20–3/20/20

KCET Curriculum-Related Programming 3/16/20–3/20/20 GRADES 9–12 TIME MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY 9 :00 AM The Woman The Woman Masterpiece: American Masters: Margaret Mitchell* in White in White American Masters: Little Women Part Two* Part Three 9 :30 AM Part Two* Louisa May Alcott* ELA ELA ELA ELA 10:00 AM ELA The Woman in The Woman The Woman Masterpiece: White in White in White Little Women Part One* Part Three* Part Five* 10:30 AM Part Three* Masterpiece: ELA ELA ELA ELA Little Women 11:00 AM Part One* African Americans: African Americans: African Americans: African Americans: ELA The Black Atlantic The Age of Slavery Into the Fire Making a Way Out Part Two Part Three 11:30 AM Part One of No Way Part Four Social Studies Social Studies Social Studies 8 Days to the Social Studies 12:00 PM Moon and Back* Latino Americans: Latino Americans: Latino Americans: Latino Americans: Foreigners in Their Empire of Dreams War and Peace Part The New Latinos Social Studie s Three* Part Four* 1 2:30 PM Own Land Part One* Part Two* Social Studies Social Studies Social Studies Social Studies 1 :00 PM Big Pacific: Big Pacific: Big Pacific: Big Pacific: Voracious Passionate A Year in Space* Mysterious Violent 1 :30 PM Part Three* Part Four* Part One* Part Two* Science Science Science Science Science 2:00 PM OVA NOVA: NOVA: NOVA: NOVA: N : Mars* Jupiter* Saturn* Ice Worlds* 2:30 PM Inner Worlds* Science Science Sc i en ce Science Science 3 :00 PM *Shows designated with asterisks are available to stream on the PBS Video and PBS KIDS Apps Access educational resources aligned with these PBS programs by visiting: kcet.org/athomelearning To stream these and other PBS programs, download the PBS Video and PBS KIDS Apps. -

Jacob Lawrence a Biography Timeline

Jacob Lawrence Timeline a biography Jacob Lawrence, born on September 7, 1917, in Atlantic City, New The easel division required that artists submit two paintings every six weeks, which gave Jersey, first moved to Easton, Pennsylvania at the age of two and Lawrence free time to research and create two series of paintings on Frederick Douglass and Harriet 1910 then relocated to Philadelphia in 1924 after his parents separated. Tubman. People began to talk about his work and both The Life of Frederick Douglass (1939) and The Lawrence’s mother, unable to find a steady job, moved to New York Life of Harriet Tubman (1940) were exhibited at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., for the 75th where she believed there would be more economic opportunity. anniversary of the Thirteenth Amendment. Lawrence and his siblings stayed in Philadelphia, moving between In 1940 Lawrence began research for a huge project called The Migration of the Negro. All 60 foster homes until 1930, when they rejoined their mother in New panels were completed in 1941 with the assistance of artist Gwendolyn Knight (the two artists married 1917 Jacob Lawrence York. The city was exciting for young Lawrence, who loved to later that year). was an instant success, and Downtown Gallery exhibited it, The Migration of the Negro is born on September 7 in observe the constant activity in his Harlem neighborhood. In the subsequently making Lawrence the first African American artist to be represented by a major New York Atlantic City, New Jersey 1930s, almost 35,000 African Americans lived within five square commercial gallery.