9-Sonali Mukherjee.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odisha District Gazetteers Nabarangpur

ODISHA DISTRICT GAZETTEERS NABARANGPUR GOPABANDHU ACADEMY OF ADMINISTRATION [GAZETTEERS UNIT] GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA ODISHA DISTRICT GAZETTEERS NABARANGPUR DR. TARADATT, IAS CHIEF EDITOR, GAZETTEERS & DIRECTOR GENERAL, TRAINING COORDINATION GOPABANDHU ACADEMY OF ADMINISTRATION [GAZETTEERS UNIT] GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA ii iii PREFACE The Gazetteer is an authoritative document that describes a District in all its hues–the economy, society, political and administrative setup, its history, geography, climate and natural phenomena, biodiversity and natural resource endowments. It highlights key developments over time in all such facets, whilst serving as a placeholder for the timelessness of its unique culture and ethos. It permits viewing a District beyond the prismatic image of a geographical or administrative unit, since the Gazetteer holistically captures its socio-cultural diversity, traditions, and practices, the creative contributions and industriousness of its people and luminaries, and builds on the economic, commercial and social interplay with the rest of the State and the country at large. The document which is a centrepiece of the District, is developed and brought out by the State administration with the cooperation and contributions of all concerned. Its purpose is to generate awareness, public consciousness, spirit of cooperation, pride in contribution to the development of a District, and to serve multifarious interests and address concerns of the people of a District and others in any way concerned. Historically, the ―Imperial Gazetteers‖ were prepared by Colonial administrators for the six Districts of the then Orissa, namely, Angul, Balasore, Cuttack, Koraput, Puri, and Sambalpur. After Independence, the Scheme for compilation of District Gazetteers devolved from the Central Sector to the State Sector in 1957. -

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT for the PROPOSED 7.0 MTPA BAILADILA IRON ORE MINE DEPOSIT NO.4 at BHANSI, NEAR BACHELI, SOUTH BASTAR DANTEWADA DISTRICT, CHHATTISGARH

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT for THE PROPOSED 7.0 MTPA BAILADILA IRON ORE MINE DEPOSIT NO.4 AT BHANSI, NEAR BACHELI, SOUTH BASTAR DANTEWADA DISTRICT, CHHATTISGARH EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Sponsor: NMDC Limited Hyderabad Prepared by : Vimta Labs Ltd. 142 IDA, Phase-II, Cherlapally Hyderabad–500 051 [email protected], www.vimta.com April, 2015 Environmental Impact Assessment for Proposed 7.0 MTPA Bailadila Iron Ore Mine Deposit No.4 at Bhansi, near Bacheli, South Bastar Dantewada District, Chhattisgarh Executive Summary 1.0 INTRODUCTION NMDC Limited a Navaratna company and Government of India Enterprise under administrative control of Ministry of Steel is operating iron ore mining projects at Bailadila range of hills since 1968. The iron ore produced from Bailadila mines is catering the iron ore requirement of major steel plants of Government and Private sector and also many pellet / sponge iron ore plants in C.G state and also outside the state. NMDC Limited proposes for Iron ore mining at Bailadila Deposit No.4 at Bhansi near Bacheli, South Bastar Dantewada district, Chhattisgarh with a production capacity of 7.0 MTPA. The mine lease area is 646.596 ha falls in Bailadila Reserve Forest land, Bacheli forest range, Dantewada forest division, Chhattisgarh. The iron ore mining project is proposed to be developed for meeting the iron ore requirement of upcoming Integrated Steel Plant of 3.0 MTPA capacity of NMDC Limited at Nagarnar, Bastar District, C.G. The iron ore requirement for the above steel plant would be 5 MTPA. In order to maintain continuous and assured supply of raw material i.e iron ore, development of iron ore mining project at Bailadila Deposit no: 4 is very much essentially required. -

Sukma, Chhattisgarh)

1 Innovative initiatives undertaken at . Cashless Village Palnar (Dantewada) . Comprehensive Education Development (Sukma, Chhattisgarh) . Early detection and screening of breast cancer (Thrissur) . Farm Pond On Demand (Maharashtra) . Integrated Solid Waste Management and Generation of Power from Waste (Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh) . Rural Solid Waste Management (Tamil Nadu) . Solar Urja Lamps Project (Dungarpur) . Spectrum Harmonization and Carrier Aggregation . The Neem Project (Gujarat) . The WDS Project (Surguja, Chhattisgarh) Executive Summary Cashless Village Palnar (Dantewada) Background/ Initiatives Undertaken • Gram Panchayat Palnar, made first cashless panchayat of the state • All shops enabled with cashless mechanism through Ezetap PoS, Paytm, AEPS etc. • Free Wi-Fi hotspot created at the market place and shopkeepers asked to give 2-5% discounts on digital transactions • “Digital Army” has been created for awareness and promotion – using Digital band, caps and T-shirts to attract localities • Monitoring and communication was done through WhatsApp Groups • Functional high transaction Common Service Centers (CSC) have been established • Entire panchayat has been given training for using cashless transaction techniques • Order were issued by CEO-ZP, Dantewada for cashless payment mode implementation for MNREGS and all Social Security Schemes, amongst multiple efforts taken by district administration • GP Palnar to also facilitate cashless payments to surrounding panchayats Key Achievements/ Impact • Empowerment of village population by building confidence of villagers in digital transactions • Improvement in digital literacy levels of masses • Local festivals like communal marriage, traditional folk dance festivals, inter village sports tournament are gone cashless • 1062 transactions, amounting to Rs. 1.22 lakh, done in cashless ways 3 Innovation Background Palnar is a village located in Kuakonda Tehsil of Dakshin Bastar Dantewada district in Chhattisgarh. -

Socio-Economic Survey Report of Villages in Dantewada

SOCIO-ECONOMIC SURVEY & NEEDS ASSESSMENT STUDY IN ESSAR STEEL’S PROJECT VILLAGE Baseline Report of the villages located in three blocks of Dantewada in South Bastar Survey Team of Essar Foundation Deepak David Dr. Tej Prakash Pratik Sethe Socio-economic survey and Need assessment study Kirandul, Dist. Dantewada- Chhattisgarh TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1. ESSAR STEEL INDIA LIMITED, VIZAG OPERATIONS - BENEFICIATION PLANT 1.2. ESSAR FOUNDATION 1.3. PROJECT LOCATION 1.4. OBJECTIVE 1.5. METHODOLOGY 1.6. STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT CHAPTER 2 AREA PROFILE 2.1. DISTRICT PROFILE 2.2. PROFILE OF THE VILLAGES 2.2.1. Location and Layout 2.2.2. Settlement pattern 2.2.3. Population 2.2.4. Sex Ratio 2.2.5. Literacy 2.2.6. Occupation 2.2.7. Education 2.2.8. Health services 2.2.9. Electrification 2.2.10. Road and transportation 2.2.11. Communication facilities CHAPTER 3 FINDING OF THE HOUSEHOLD SURVEY 3.1. BACKGROUND 3.2. METHODOLOGY 3.3. SOCIO- ECONOMIC PROFILES OF THE VILLAGES ESSAR FOUNDATION Page 2 of 86 Socio-economic survey and Need assessment study Kirandul, Dist. Dantewada- Chhattisgarh 3.3.1. # of HH members; Average # of members in HH 3.3.2. Caste/ Tribe and sub-group 3.3.3. Age- Sex Distribution 3.3.4. Marital Status 3.3.5. Literacy Rate 3.3.6. Migration 3.3.7. Occupation pattern 3.3.8. Employment and income 3.3.9. Dependency Ratio 3.3.10. Participation in Public Program 3.3.11. Livestock Population 3.3.12. -

Residential Schools for Children in LWE-Affected Areas of Chhattisgarh

EDUCATION 2.3 Pota Cabins: Residential schools for children in LWE-affected areas of Chhattisgarh Pota Cabins is an innovative educational initiative for building schools with impermanent materials like bamboo and plywood in Chhattisgarh. The initiative has helped reduce the number of out-of-school children and improve enrolment and retention of children since its introduction in 2011. The number of out-of-school children in the 6-14 years age group reduced from 21,816 to 5,780 as the number of Pota Cabins rose from 17 to 43 within a year of the initiative. These residential schools help ensure continuity of education from primary to middle-class levels in Left Wing Extremism affected villages of Dantewada district, by providing children and their families a safe zone where they can continue their education in an environment free of fear and instability. Rationale Secondly, it would also draw children away from the remote and interior areas of villages that are more prone to Left Wing Extremists violence. As these schools are perceived The status of education in Dantewada district of Chhattisgarh as places where children can receive adequate food and was abysmal. As per a 2005 report, the literacy rate of the education, they are often referred to Potacabins locally, as state stood at 30.2% against the state average of 64.7%.1 ‘pota’ means ‘stomach’ in the local Gondi language. The development deficit in the Dakshin Bastar area, which includes Dantewada district, has been largely attributed to the remoteness of villages, lack of proper infrastructure Objectives such as roads and bridges, and weak penetration of communication technology. -

Bailadila Iron Ore Deposit-4 • Reg Ref: Regulation 30 of the SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015; Security 10: NMDC

~ ~ it -{fr f{:t ~~s NMDC Limited (1JRn ~ i6'l \RPI) (A GOVT. OF INDIA ENTERPRISE) ~ ~<t>~14'"'\~C'1~4 : ·~ ~· . 10- 3-311~. ~ ~. 11ffiTEl ~. ~~c:~x~1=~1"""C: - 500 028. Regd. Office: 'Khanij Bhavan' 10-3-311/A, Castle Hills, Masab Tank, Hyderabad - 500 028. NMDC ~~~I Corporate Identity Number: L 13100TG1958 GOI 001674 No. 18( 1J/2021 - Sectt 6th July 2021 1. The BSE Limited 2. National Stock Exchange of India Ltd., Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers, Dalal Exchange Plaza, C-1 , Block G, Street, Mumbai- 400001 Bandra Kurla Complex, Sandra (E), Mumbai - 400 051 3. The Calcutta Stock Exchange Limited, 7, Lyons Range, Kolkata - 700001 Dear Sir I Madam, Sub: Letter of Intent (LOI) for grant of Mining Lease • Bailadila Iron Ore Deposit-4 • Reg Ref: Regulation 30 of the SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015; Security 10: NMDC The Mineral Resource Department, Government of Chhattisgarh vide letter dated 261h June 2021 has issued Letter of Intent (LOI) for Bailadila Iron Ore Mine, Deposit-4, South Bastar, Dantewada District in favour of NMDC-CMDC Limited (NCL). Raipur, a JV Company of NMDC Limited (holding 513 equity share capital) along with CMDC (Chhattisgarh Mineral Development Corporation) (holding 493 equity share capital) , for iron ore mining over 646.596 Ha.in Dantewada Forest Division, Chhattisgarh. Bailadila Iron Ore Deposit-4 is located north of Deposit-5 on the western flank of the Bailadila range of hills, lying at a distance of about l 35 kms towards south-west of Jagdalpur. It is a big and homogeneous iron ore deposit having onsite Reserve of approximately l 07 MT with an average grade of Fe of 65.39 3 . -

Chhattisgarh)

STATE REVIEWS Indian Minerals Yearbook 2016 (Part- I) 55th Edition STATE REVIEWS (Chhattisgarh) (FINAL RELEASE) GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF MINES INDIAN BUREAU OF MINES Indira Bhavan, Civil Lines, NAGPUR – 440 001 PHONE/FAX NO. (0712) 2565471 PBX : (0712) 2562649, 2560544, 2560648 E-MAIL : [email protected] Website: www.ibm.gov.in February, 2018 11-1 STATE REVIEWS CHHATTISGARH sand in Durg, Jashpur, Raigarh, Raipur & Rajnandgaon districts; and tin in Bastar & Mineral Resources Dantewada districts (Table - 1 ). The reserves/ Chhattisgarh is the sole producer of tin resources of coal are furnished in Table - 2. concentrates and moulding sand. It is one of the Exploration & Development leading producers of coal, dolomite, bauxite and The details of exploration activities conducted iron ore. The State accounts for about 36% tin by GSI, NMDC and State DGM during 2015-16 are ore, 22% iron ore (hematite), 11% dolomite and furnished in Table - 3. 4% each Diamond & marble resources of the country. Important mineral occurrences in the Production State are bauxite in Bastar, Bilaspur, Dantewada, The total estimated value of mineral produc- Jashpur, Kanker, Kawardha (Kabirdham), Korba, tion (excludes atomic mineral) in Chhattisgarh at Raigarh & Sarguja districts; china clay in Durg & ` 21,149 crore in 2015-16, decreased by about Rajnandgaon districts; coal in Koria, Korba, 11% as compared to that in the previous year. Raigarh & Sarguja districts; dolomite in Bastar, The State is ranked fourth in the country and Bilaspur, Durg, Janjgir-Champa, Raigarh & Raipur accounted for about 7% of the total value of min- districts; and iron ore (hematite) in Bastar district, eral production. -

15 October 2019 India

15 October 2019 India: Attacks and harassment of human rights defenders working on indigenous and marginalized people's rights On 5 October 2019, Soni Sori was arrested by the Dantewada Police under Preventive Sections 151, 107 and 116 of the Indian Code of Criminal Procedure. The arrest is believed to be linked to the human rights defender’s public campaign for the rights of persons languishing in jails in the State. Soni Sori was charged with “failing to obtain the necessary permission to organise a demonstration”. She was released on bail by the local court that same day. On 16 September 2019, the Chhattisgarh police filed a First Information Report (FIR) against Soni Sori and human rights defender Bela Bhatia. This FIR is believed to be a reprisal against the two human rights defenders for their participation in a protest and their filing of a complaint in the Kirandul police station demanding that an FIR be lodged against the police and security forces for the killings of human rights defenders, Podiya Sori and Lacchu Mandavi. Soni Sori is a human rights defender who advocates for the rights of indigenous people in India, with a focus on women's rights. She works in Chhattisgarh, where the long-term conflict between Maoists and government security forces has greatly affected the indigenous people in the area. Alongside other human rights defenders, she has uncovered human rights violations committed by both sides of the conflict. In 2018, Soni Sori was the regional winner of the Front Line Defenders Award for human rights defenders at risk. -

Sustainable Agriculture – a New Partnership Paradigm in Dantewada Harsh Jaiswal, TERI University 1

Sustainable Agriculture – A New Partnership Paradigm in Dantewada Harsh Jaiswal, TERI University 1. Heralding Green Revolution in Independent India Upon breaking the shackles of colonisation in 1947, India was plagued with starvation and famine in several parts of the country. As a young independent nation, agricultural production wasn’t sufficient for the growing population. Several causes have been attributed to this glaring gap between supply and demand. Lack of modernisation in the agriculture sector and the prevalence of primitive methods of farming were attributed as the major cause. In the early 1960s, the Green Revolution (henceforth, GR) was pedestaled as the saviour of India’s farmers and food deficient people. This involved the use of chemical fertilizers, irrigation infrastructure, and high yielding variety (HYVs). GR promised to tackle chronic food deficit by increasing yield and making the country self-sufficient in food grain production. These developments were supported with institutional interventions like Minimum Support Price (MSP) protocol, subsidies on chemical fertilizers, improvement in rural infrastructure, and so on. 1.1 Contestations on Green Revolution However, the critical appraisal on GR highlights some of the major problems in the technical interventions with serious environmental and economic consequences. “However the assumption of nature as a source of scarcity, and technology as a source of abundance, leads to the creation of technologies which create new scarcities in nature through ecological destruction. The reduction in the availability of fertile land and genetic diversity of crops as a result of the Green Revolution practices indicates that at the ecological level , the Green Revolution produced scarcity, not abundance” (Shiva, 1991) Evidence suggests that the Indian states of Punjab, Haryana, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, and Andhra Pradesh are currently reaping the repercussions of GR. -

MAT Ilial for FOREST FLORA of MADHYA PRADESH

MAT ilIAL FOR FOREST FLORA OF MADHYA PRADESH st. or t =.4—e 11" • " S. F. R. I Bulletin No. 28 MATERIAL FOR FOREST FLORA OF MADHYA PRADESH Dr. R.K. Pandey Forest Botanist AND Dr. J. L. Shrivastava Herbarium Keeper MADHYA PRADESH, STATE FOREST RESEARCH INSTITUTE JABALPUR 1996 CONTENTS Pg.No. Introduction 3 Statistical Analysis of Flora 8 List of species with information 14 Bibliography 164 Index 169 3 MATERIAL FOR FOREST FLORA OF MADHYA PRADESH INTRODUCTION Madhya Pradesh is the largest State in the Indian Union. Its geographical area is 443.4 thousand sq km which is nearly 13.5% of the geographical area of the country. It is centrally located and occupied the heart of the country. The state is bordered by seven states viz. Utter Pradesh, Bihar, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh, Maharastra, Gujarat and Rajasthan. (Map 1) Madhya Pradesh is situated in the centre between lattitude 170-48'N to 280-52' N and between longitudes 740-0' E to 840-24' E. Undulating topography characterized by low hills, narrow valleys, well defined plateau and plains is the general physiography of the tract which separates the fertile Gangetic plains of Utter Pradesh in the north from the broad table land of Deccan in the south. The elevation varies from over 61 m to 1438m above mean see level. The major protion of the Catchments of many important rivers like the Narmada, the Mahanadi, the Tapti, Wainganga, the Son, the Chan hal and the Manvi lie in Madhya Pradesh. The forests occupy an area of 155.414 sq km which comes to about 35% of the total land area of the state and about 22% at the total forest area of the country, these forests are not evenly distributed in the state. -

Indian Society of Engineering Geology

Indian Society of Engineering Geology Indian National Group of International Association of Engineering Geology and the Environment www.isegindia.org List of all Titles of Papers, Abstracts, Speeches, etc. (Published since the Society’s inception in 1965) November 2012 NOIDA Inaugural Edition (All Publications till November 2012) November 2012 For Reprints, write to: [email protected] (Handling Charges may apply) Compiled and Published By: Yogendra Deva Secretary, ISEG With assistance from: Dr Sushant Paikarai, Former Geologist, GSI Mugdha Patwardhan, ICCS Ltd. Ravi Kumar, ICCS Ltd. CONTENTS S.No. Theme Journal of ISEG Proceedings Engineering Special 4th IAEG Geology Publication Congress Page No. 1. Buildings 1 46 - 2. Construction Material 1 46 72 3. Dams 3 46 72 4. Drilling 9 52 73 5. Geophysics 9 52 73 6. Landslide 10 53 73 7. Mapping/ Logging 15 56 74 8. Miscellaneous 16 57 75 9. Powerhouse 28 64 85 10. Seismicity 30 66 85 11. Slopes 31 68 87 12. Speech/ Address 34 68 - 13. Testing 35 69 87 14. Tunnel 37 69 88 15. Underground Space 41 - - 16. Water Resources 42 71 - Notes: 1. Paper Titles under Themes have been arranged by Paper ID. 2. Search for Paper by Project Name, Author, Location, etc. is possible using standard PDF tools (Visit www.isegindia.org for PDF version). Journal of Engineering Geology BUILDINGS S.No.1/ Paper ID.JEGN.1: “Excessive settlement of a building founded on piles on a River bank”. ISEG Jour. Engg. Geol. Vol.1, No.1, Year 1966. Author(s): Brahma, S.P. S.No.2/ Paper ID.JEGN.209: “Geotechnical and ecologial parameters in the selection of buildings sites in hilly region”. -

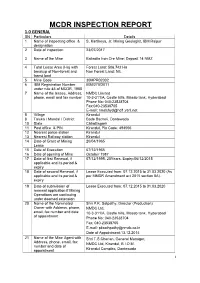

MCDR INSPECTION REPORT 1.0 GENERAL SN Particulars Details 1 Name of Inspecting Office & S

MCDR INSPECTION REPORT 1.0 GENERAL SN Particulars Details 1 Name of inspecting office & S. Kartikeya, Jr. Mining Geologist, IBM Raipur designation 2 Date of inspection 23/07/2017 3 Name of the Mine Bailadila Iron Ore Mine; Deposit 14 NMZ 4 Total Lease Area (Ha) with Forest Land: 506.742 Ha breakup of Non-forest and Non Forest Land: NIL forest land 5 Mine Code 30MPR02002 6 IBM Registration Number IBM/270/2011 under rule 45 of MCDR, 1988 7 Name of the lessee, Address, NMDC Limited phone, email and fax number 10-3-311/A, Castle hills, Masab tank, Hyderabad Phone No: 040-23538704 Fax:040-23538705 E-mail: [email protected] 8 Village Kirandul 8 Taluka / Mandal / District Bade Bacheli, Dantewada 10 State Chhattisgarh 11 Post office & PIN Kirandul, Pin Code: 494556 12 Nearest police station Kirandul 13 Nearest Railway station Kirandul 14 Date of Grant of Mining 20/04/1965 Lease 15 Date of Execution 07/12/1965 16 Date of opening of Mine October 1987 17 Date of first Renewal, if 07/12/1995, 20Years, Expiry-06/12/2015 applicable and its period & expiry 18 Date of second Renewal, if Lease Executed from: 07.12.2015 to 31.03.2020 (As applicable and its period & per MMDR Amendment act 2015 section 8A). expiry 19 Date of submission of Lease Executed from: 07.12.2015 to 31.03.2020 renewal application if Mining Operations are continuing under deemed extension 20 Name of the Nominated Shri P.K. Satpathy, Director (Production) Owner with Address, phone, NMDC Ltd, email, fax number and date 10-3-311/A, Castle hills, Masab tank, Hyderabad of appointment Phone No: 040-23538704 Fax: 040-23538705 E-mail: [email protected] Date of Appointment:13.12.2014 21 Name of the Mine Agent with Shri T.S.Cherian, General Manager, Address, phone, email, fax NMDC Ltd, Kirandul, B.I.O.M.