MCEA Comment on Hiawatha Campus Expansion Project.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microsoft Azure Essentials Azure Machine Learning

Azure Machine Learning Microsoft Azure Essentials Jeff Barnes Visit us today at microsoftpressstore.com • Hundreds of titles available – Books, eBooks, and online resources from industry experts • Free U.S. shipping • eBooks in multiple formats – Read on your computer, tablet, mobile device, or e-reader • Print & eBook Best Value Packs • eBook Deal of the Week – Save up to 60% on featured titles • Newsletter and special offers – Be the first to hear about new releases, specials, and more • Register your book – Get additional benefits Hear about it first. Get the latest news from Microsoft Press sent to your inbox. • New and upcoming books • Special offers • Free eBooks • How-to articles Sign up today at MicrosoftPressStore.com/Newsletters Wait, there’s more... Find more great content and resources in the Microsoft Press Guided Tours app. The Microsoft Press Guided Tours app provides insightful tours by Microsoft Press authors of new and evolving Microsoft technologies. • Share text, code, illustrations, videos, and links with peers and friends • Create and manage highlights and notes • View resources and download code samples • Tag resources as favorites or to read later • Watch explanatory videos • Copy complete code listings and scripts Download from Windows Store PUBLISHED BY Microsoft Press A division of Microsoft Corporation One Microsoft Way Redmond, Washington 98052-6399 Copyright © 2015 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved. No part of the contents of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-7356-9817-8 Microsoft Press books are available through booksellers and distributors worldwide. -

Data Localization Requirements Across Different Jurisdictions 70

The Localisation Gambit Unpacking Policy Measures for Sovereign Control of Data in India 19th March, 2019 By Arindrajit Basu, Elonnai Hickok, and Aditya Singh Chawla Edited by Pranav M Bidare, Vipul Kharbanda, and Amber Sinha Research Assistance Anjanaa Aravindan The Centre for Internet and Society, India Acknowledgements 2 Executive Summary 3 Introduction 9 Methodology 10 Defining and Conceptualizing Sovereign Control of Data 11 Mapping of Current Policy Measures for Localization of Data in India 13 The Draft Personal Data Protection Bill, 2018 13 Draft E-commerce Policy (s) 17 RBI Notification on ‘Storage of Payment System Data’ 19 Draft E-Pharmacy Regulations 20 FDI Policy 2017 20 National Telecom M2M Roadmap 21 Unified Access License for Telecom 21 Companies Act, 2013 and Rules 21 The IRDAI (Outsourcing of Activities by Indian Insurers) Regulations, 2017 22 Guidelines on Contractual Terms Related to Cloud Services 22 Reflecting on Objectives, Challenges and Implications of National Control of Data 24 Enabling Innovation and Economic Growth 24 Enhancing National Security and Law Enforcement Access 34 Law Enforcement Access 34 Protecting Against Foreign Surveillance 36 Threat to fibre-optic cables 37 Widening Tax Base 40 Data Sovereignty and India’s Trade Commitments 41 A Survey of Stakeholder Responses 48 Data Localisation Around the World 49 Conclusions and Recommended Approaches 61 Annexure I 70 Mapping Data Localization Requirements Across Different Jurisdictions 70 Annexure 2 75 A survey of stakeholder responses 75 1 Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank Pranav MB, Vipul Kharbanda, Amber Sinha, and Saumyaa Naidu for their invaluable edits and comments on the draft. -

Revised Agenda Meeting Of

REVISED AGENDA MEETING OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY Thursday, December 13, 2018 Approximately 10 a.m. Ballroom B Student Center Southern Illinois University Carbondale Call to Order by Chair Pledge of Allegiance Roll Call Approval of Minutes of the Meetings Held September 12 and 13, 2018, and November 9, 2018 BOARD OF TRUSTEES ACTIVITIES A. Trustee Reports B. Committee Reports Executive Committee EXECUTIVE OFFICER REPORTS C. President, Southern Illinois University D. Chancellor, Southern Illinois University Carbondale E. Chancellor, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville F. Dean and Provost, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine PUBLIC COMMENTS AND QUESTIONS RECEIPT OF INFORMATION AND NOTICE ITEMS G. Report of Purchase Orders and Contracts, August, September and October 2018, SIUC H. Report of Purchase Orders and Contracts, August, September and October 2018, SIUE RATIFICATION OF PERSONNEL MATTERS I. Changes in Faculty-Administrative Payroll – SIUC J. Changes in Faculty-Administrative Payroll – SIUE ITEMS RECOMMENDED FOR APPROVAL BY THE PRESIDENT K. Approval of Change to 5 Policies of the Board A, Budgets and Article III, Section 3 of Board Bylaws L. Approval of Administrative Reorganization of Academic Units and the Use of the Reasonable and Moderate Extension Process of the Illinois Board of Higher Education, SIUC M. Approval of Purchase: Constituent Relations Management Software, Carbondale Campus, SIUC N. Project and Budget Approval and Award of Contract: Turf Replacement Saluki Stadium, Carbondale Campus, SIUC O. Approval of Purchase: Aircraft for Aviation Flight Program, SIUC P. Approval of Purchase: Electrical Supplies, Carbondale Campus, SIUC Q. Award of Contract: Medical Instruction Facility, Lobby Renovations, School of Medicine Campus, SIUC R. -

Supplies and Services Contracts, Dated July 2010

1. Caption Page of Pages SOLICITATION, OFFER, AND AWARD DOC Offender Management System 1 93 2. Contract Number 3. Solicitation Number 4. Type of Solicitation 5. Date Issued 6. Type of Market Sealed Bid (IFB) Open Sealed Proposals (RFP) 11/07/17 Set Aside Doc350609 Sole Source Open Market with Set-Aside Emergency CBE Designated Category 7. Issued By 8. Address Offer to: Office of Contracting and Procurement Office of Contracting and Procurement 441 - 4th Street, N.W., Suite 700 South 441 - 4th Street, N.W., Suite 700 South Washington, D.C. 20001 Washington, D.C. 20001 NOTE: In sealed bid solicitations “offer” or “offeror” means “bid or “bidder” SOLICITATION 9. Sealed offers in original and __1__ copies for furnishing the supplies or services in the Schedule will via electronic format via the on-line solicitation software __2:00 p.m. local time December 7, 2017 _ (Hour) (Date) CAUTION: Late submission, Modifications and Withdrawals: See 27 DCMR chapters 15 & 16 as applicable. All offers are subject to all terms & conditions contained in solicitation. 10. For Information A. Name B. Telephone C. E-mail Address Contact (Area Code) (Number) (Ext) Nicole Smith-McDermott 202 724.4587 [email protected] 11. Table of Contents (X) Section Description Page (X) Section Description Page No. No. PART I – THE SCHEDULE PART II – CONTRACT CLAUSES X A Solicitation/Contract Form 1 X I Contract Clauses 66 X B Supplies or Services and Price/Cost 2 PART III – LIST OF DOCUMENTS, EXHIBITS AND OTHER ATTACHMENTS X C Specifications/Work Statement 5 X J List of Attachments 76 X D Packaging and Marking 46 PART IV – REPRESENTATIONS AND INSTRUCTIONS X E Inspection and Acceptance 46 Representations, certification and other 77 X F Deliveries or Performance 47 X K statements of offerors X G Contract Administration Data 51 X L Instructions, conditions & notices to Offerors 78 X H Special Contract Requirements 58 X M Evaluation factors for award 88 12. -

Lutheran Campus Ministry of Illinois 1988 ----- ALC, AELC and LCA Merge to Form ELCA in 1988

History of Lutheran Campus Ministry in the U.S.A. 1907 ---- University of Wisconsin, Madison is first campus ministry agency. Dr. Harry Gold is called as “student Pastor” 1922 ---- Lutheran Student Association of America (LSAA) is formed 1928 ---- Gamma Delta – the student organization for the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod is formed. 1945 ---- World War II ends – veterans return and swell the ranks of campus ministry. National Lutheran Council (NLC) composed of 8 national Lutheran church bodies: AELC - ALC - Augustana - ELC - FLC – Suomi - UELC - ULCA 1946 ---- Commission for Student Service formed under NLC 1952 ---- “CSS” becomes “Division for Student Services” 1956 ---- “DSS” becomes “Division for College and University Work” 1960 ---- ALC merger occurred 1962 ---- LCA merger occurred (now two national bodies in NLC) 1964 ---- Joint LSAA and Gamma Delta Conference calls for the merger of the ALC, LCA and LCMS 1967 ---- Lutheran Council in the USA (LCUSA) succeeds the NLC and Includes Missouri Synod but National Lutheran Campus Ministry (NLCM) an agency of the ALC and LA was extra-conciliar from 1967-1969 1969 ---- NLCM becomes a “program unit” of LCUSA’s “Division for Educational Services” Lutheran Student Movement-USA is formed - a merger of LSAA and Gamma Delta. 1975 ---- “DES” becomes LCUSA’s “Division for Campus Ministry and Educational Services” 1982 ---- “DCMES” becomes LCUSA’s “Division for Campus Ministry” 1985 ----- LSM-USA becomes the first Lutheran “Reconciled in Christ” organization. Gamma Delta withdraws and become Lutheran -

* * * D R a F T * * * 1.0 Purpose of And

North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study * * * D R A F T * * * 1.0 Purpose of and Need for Action The North Lake Shore Drive (NLSD) study corridor extends approximately seven miles from Grand Avenue to Hollywood Avenue. See Exhibits 1 and 2 in Appendix A. The corridor is comprised of the eight-lane “Outer Drive“ boulevard and the parallel two to four-lane “Inner Drive” local access roadway that is variously named North Lake Shore Drive, Sheridan Road and Marine Drive. The Outer Drive is designated as US 41 from the south study limit to Foster Avenue, where the US route designation continues west on Foster. The Outer Drive between Foster Avenue and the northern terminus at Hollywood Avenue is an unmarked State route. The Outer Drive is on the National Highway System which consists of roadways that are important to the nation’s economy, defense and mobility. North Lake Shore Drive is located primarily within Lincoln Park which is a 1,200-acre regional park dating back to 1860 that is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Since its inception, NLSD has been a heavily used transportation artery in the lakefront corridor and it has evolved into an important multi- modal facility. It is a major north-south corridor through the city as it provides regional connectivity between the north and south suburbs as well as a link to the central business district. Today, the corridor carries as many as 161,000 cars per day as well as 970 Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) buses with 69,000 passengers per day along the Inner and/or the Outer Drives as shown on Exhibits 3 and 4 in Appendix A. -

YGH 50Th Anniversary Exhibit Booklet

The world is a fascinating place. Over the last 50 years we have had the honor and good fortune to build rich relationships and partner with colleagues and clients in the Northwest and over 40 countries around the globe. Here’s to 50 years of captivating, challenging, award-winning and just plain fun projects. 64 70 80 BUILDING A UNIQUE PRACTICE GROWTH & CHANGE Campbell Yost Grube “As in nature, the aesthetic qualities in architecture are derived from the way things work.” CAMPBELL YOST GRUBE ARCHITECTS YOST GRUBE HALL ARCHITECTS 90 2000 EVOLUTION & POSSIBILITY “Projects in the developing world have taught us to focus on the essential...” “... to produce architecture of excellence in service to our clients and society.” YGH ARCHITECTURE “From the Northwest, across the U.S. and to the Sudan...It’s been quite an adventure.” -Joachim Grube Building a Unique Practice Consider this: 50 years ago there were no computers. A GPS system was a well-worn map that folded 60 nicely in your back pocket. The level of communication we take for granted today didn’t exist. That didn’t make it any less exciting to be a small, young architecture fi rm hungry to make a difference. The fi rm’s focus on creative “problem seeking” led to signifi cant projects for the State of Oregon and the Oregon Board of Higher Education, as well as a national building program and work overseas. 70 60 -70’s Portland State University Campus Master Plans YGH developed three major campus plans for Portland State University from 1970 to 1985. -

Arriving on Campus – Directions/Ground Transportation, Parking, Accomodations

ARRIVING ON CAMPUS – DIRECTIONS/GROUND TRANSPORTATION, PARKING, ACCOMODATIONS Please visit the University of Pennsylvania's website for general directions on how to reach campus by car, train, or plane- http://www.admissions.upenn.edu/visiting/directions.php. College Hall, per the directions on this link, is next to Houston Hall, where the fair is being held. More detailed directions to Houston Hall (use drop down menu on top right): http://www.vpul.upenn.edu/perelmanquad/direction-parking.php Area Map: http://www.vpul.upenn.edu/perelmanquad/assets/attend/perelman-area- map-2012.pdf DIRECTIONS: The University of Pennsylvania campus is located in an area of West Philadelphia known as University City. See below for a map of the area. From the Philadelphia International Airport: SEPTA Airport Express Train The Airport Express Train (R1 line) leaves 4 minutes after every half hour from the 30th Street Station. The fare is $5.50 and the ride takes about 20 minutes. Fares and schedules are available at http://www.septa.com The train also makes a stop at the University City Station on Penn’s campus. Cars, Taxis and Limousines at the Airport A metered taxicab costs about $25-$30 including tip and the ride takes about 20 minutes. The Inn at Penn and the Sheraton also offer airport shuttle service, inquire at the front desk. Amtrak or SEPTA trains 30th Street Station: all Amtrak Northeast Corridor trains & SEPTA Regional trains stop here. * From campus you can walk to the station in about 15 minutes. * A metered cab costs about $5 including tip and the ride takes about 5 minutes. -

Historic Properties Identification Report

Section 106 Historic Properties Identification Report North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study E. Grand Avenue to W. Hollywood Avenue Job No. P-88-004-07 MFT Section No. 07-B6151-00-PV Cook County, Illinois Prepared For: Illinois Department of Transportation Chicago Department of Transportation Prepared By: Quigg Engineering, Inc. Julia S. Bachrach Jean A. Follett Lisa Napoles Elizabeth A. Patterson Adam G. Rubin Christine Whims Matthew M. Wicklund Civiltech Engineering, Inc. Jennifer Hyman March 2021 North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... v 1.0 Introduction and Description of Undertaking .............................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Overview ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 NLSD Area of Potential Effects (NLSD APE) ................................................................................... 1 2.0 Historic Resource Survey Methodologies ..................................................................................... 3 2.1 Lincoln Park and the National Register of Historic Places ............................................................ 3 2.2 Historic Properties in APE Contiguous to Lincoln Park/NLSD ....................................................... 4 3.0 Historic Context Statements ........................................................................................................ -

Image- and Point Cloud-Based Detection of Damage in Robotic And

IMAGE- AND POINT CLOUD-BASED DETECTION OF DAMAGE IN ROBOTIC AND VIRTUAL ENVIRONMENTS By CALVIN DOBRIN A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Science Graduate Program in Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Written under the direction of Aaron Mazzeo And approved by _________________________________ _________________________________ _________________________________ _________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2021 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS IMAGE- AND POINT CLOUD-BASED DETECTION OF DAMAGE IN ROBOTIC AND VIRTUAL ENVIRONMENTS By CALVIN DOBRIN Thesis Director: Aaron D. Mazzeo Repair procedures are vital to maintain the integrity of long-term structures such as bridges, roads, and space habitats. To reduce the burden of manual inspection and repair of long- term environments, the proposed solution is an autonomous repair system used for damage detection and damage repair with very little human intervention. The primary purpose of this thesis is to lay the groundwork for the introductory steps related to detection of damage and creation of a virtual map for navigation in this system. It covers the process of initial detection of damage on a structure, confirmation of damage with detailed red-green-blue-depth (RGB-D) scanning, and development of a virtual map of the structure for navigation and localization of important features. We begin by reviewing numerous damage detection methods and establishing a case for optical 2D stereo imaging and 3D scanning. We performed image-processing and point cloud-processing methods to isolate damage in image and point cloud data. The potential of automating operation and data processing without human intervention is also discussed. -

FPL Florida Power & Light Company FPSC Florida Public Service Commission FPUC Florida Public Utilities Company FRCC Florida Reliability Coordinating Council F.S

I. Meeting Packet State of Florida Public Service Commission INTERNAL AFFAIRS AGENDA Tuesday, November 29, 2016 Following Special Commission Agenda Room 105 - Gerald L. Gunter Building 1. “Update from the Federal Communications Commission” by The Honorable Mignon Clyburn, FCC Commissioner 2. Draft Review of the 2016 Telecommunications Regulatory Assessment Fee Report (Attachment 1) 3. Draft Review of the 2016 Annual Report on Activities Pursuant to the Florida Energy Efficiency and Conservation Act (Attachment 2) 4. Draft Review of the 2016 Lifeline Report to the Legislature (Attachment 3) 5. Draft Review of the 2016 Ten-Year Site Plans for Florida’s Electric Utilities (Attachment 4) 6. General Counsel’s Report 7. Executive Director’s Report 8. Other Matters BB/ks OUTSIDE PERSONS WISHING TO ADDRESS THE COMMISSION ON ANY OF THE AGENDAED ITEMS SHOULD CONTACT THE OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR AT (850) 413-6463. Attachment 1 REPORT ON THE EFFORTS OF THE FLORIDA PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION TO REDUCE THE REGULATORY ASSESSMENT FEE FOR TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMPANIES As of December 2016 REPORT ON THE EFFORTS OF THE FLORIDA PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION TO REDUCE THE REGULATORY ASSESSMENT FEE FOR TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMPANIES As of December 2016 Office of Telecommunications Introduction During the 2011 Legislative Session, House Bill CS/CS/HB 1231, the “Regulatory Reform Act” (Act), was passed and signed into law by the Governor, effective July 1, 2011. Under the Act, the Legislature eliminated most of the Florida Public Service Commission’s (FPSC’s or Commission’s) retail oversight authority for the telecommunications wireline companies, yet maintained the FPSC’s authority over wholesale intercarrier issues. -

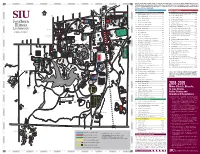

Parking Meter, 15-Minute Space Or Loading Zone from 7 A.M

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R Students, faculty and staff must display a current decal to park a vehicle or bicycle on campus, including metered spaces, 15-minute spaces and loading zones. Vehicles with a green overnight East or green overnight West or yellow commuter decal STUDIO 102 ARTS BUILDING may not use any parking meter, 15-minute space or loading zone from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday. Do not back 1 BLOCK NORTH 1 1 into spaces. All meters must be paid. Blue Decal Parking Lots Red Decal Parking Lots HESTER STREET no. description grid location no. description grid location WASHINGTON SQUARE COMPLEX 3 East Grand Avenue/Washington Street ..............O-5 RAINBOW'S END ALLEY 1 West of Lawson Hall ............................................... J-5 N RESTRICTED MARION STREET 2 THOMPSON STREET 94 70 2 6A North of Morris Library .......................................... L-5 RESERVED RESTRICTED 2 East of Anthony Hall ...............................................O-6 STOKER STREET POPLAR STREET 7 North of Pulliam Hall ............................................... L-3 86 RESERVED RESERVED RAWLINGS STREET RAWLINGS 6 North of Morris Library .......................................... L-5 LINCOLN DRIVE RAILROAD CENTRAL ILLINOIS WASHINGTON SQ. PATIENT RESTRICTED STUDENT PARKING 11 North of Travel Service ......................................... N-8 0421 FOREST AVENUE FOREST AVENUE NUE RECREATION 113 7 North of Pulliam Hall ............................................... L-3 MILL STREET SOUTH NORMAL AVENUE JAMES STREET CENTER STATE ST 14 West of University Park Commons .......................P-6 7 AFROTC VE NORTHWEST A 3 ANNEX C LO 3 9 Northwest of Pulliam Hall ......................................K-3 SOUTH OAKLAND AVENUE 0417 C KTO W ER D RIVE 5 21 RESERVED 18 South of Arena ......................................................M-13 LINCOLN DRIVE 9 19 HEALTH 10 Southeast of Anthony Hall ...................................