Economic Impact of HLF Projects Volume 1 – Main Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hospitality at the London Coliseum

Hospitality at the London Coliseum Feature 1 London Coliseum, home of English National Opera The London Coliseum was designed Whether you are planning a special by Frank Matcham in the early 20th celebration, an informal reception or Century with the ambition of being a daytime event, we have a variety of the largest and finest “people’s options tailored to your palace of entertainment”. requirements, with a truly bespoke finish. It became the home of English We look forward to working with you National Opera (then Sadler’s Wells to create your perfect event. Opera) in 1968 and is ideally located for corporate and private events in Get in touch with your dedicated the heart of London’s West End. Events Team today. Our historic Grade-II listed theatre email: [email protected] features a range of spaces perfect for call: +44 (0)20 7845 9479 daytime hire, as part of a performance package, and on non-performance evenings for your special event. With 2,359 seats, the London Coliseum is the largest theatre in London’s West End Ellis Room Royal Retiring Room A grand space in prime position Built for the Royal Family to enjoy, between the Stalls and Dress Circle. this grand room offers seclusion, privacy and a sense of grandeur. The Ellis Room, bathed in natural light and offering views over Showcasing Edwardian detail, with St. Martin’s Lane, is perfect for beautiful floor to ceiling mirrors, daytime meetings, canapé this period room has its own receptions and private dining. private washroom. One of our most popular spaces, the Recently fully furnished by Heals, Canapé reception Standing reception room has a piano as well artwork the Royal Retiring Room also celebrating the history of ENO and freautres dedicated access to the London Coliseum. -

![Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6681/theater-souvenir-programs-guide-1881-1979-256681.webp)

Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979]

Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979] RBC PN2037 .T54 1881 Choose which boxes you want to see, go to SearchWorks record, and page boxes electronically. BOX 1 1: An Illustrated Record by "The Sphere" of the Gilbert & Sullivan Operas 1939 (1939). Note: Operas: The Mikado; The Goldoliers; Iolanthe; Trial by Jury; The Pirates of Penzance; The Yeomen of the Guard; Patience; Princess Ida; Ruddigore; H.M.S. Pinafore; The Grand Duke; Utopia, Limited; The Sorcerer. 2: Glyndebourne Festival Opera (1960). Note: 26th Anniversary of the Glyndebourne Festival, operas: I Puritani; Falstaff; Der Rosenkavalier; Don Giovanni; La Cenerentola; Die Zauberflöte. 3: Parts I Have Played: Mr. Martin Harvey (1881-1909). Note: 30 Photographs and A Biographical Sketch. 4: Souvenir of The Christian King (Or Alfred of "Engle-Land"), by Wilson Barrett. Note: Photographs by W. & D. Downey. 5: Adelphi Theatre : Adelphi Theatre Souvenir of the 200th Performance of "Tina" (1916). 6: Comedy Theatre : Souvenir of "Sunday" (1904), by Thomas Raceward. 7: Daly's Theatre : The Lady of the Rose: Souvenir of Anniversary Perforamnce Feb. 21, 1923 (1923), by Frederick Lonsdale. Note: Musical theater. 8: Drury Lane Theatre : The Pageant of Drury Lane Theatre (1918), by Louis N. Parker. Note: In celebration of the 21 years of management by Arthur Collins. 9: Duke of York's Theatre : Souvenir of the 200th Performance of "The Admirable Crichton" (1902), by J.M. Barrie. Note: Oil paintings by Chas. A. Buchel, produced under the management of Charles Frohman. 10: Gaiety Theatre : The Orchid (1904), by James T. Tanner. Note: Managing Director, Mr. George Edwardes, musical comedy. -

Loyola University New Orleans Study Abroad

For further information contact: University of East London International Office Tel: +44 (0)20 8223 3333 Email: [email protected] Visit: uel.ac.uk/international Docklands Campus University Way London E16 2RD uel.ac.uk/international Study Abroad uel.ac.uk/international Contents Page 1 Contents Page 2 – 3 Welcome Page 4 – 5 Life in London Page 6 – 9 Docklands Campus Page 10 – 11 Docklands Page 12 – 15 Stratford Campus Page 16 – 17 Stratford Page 18 – 19 London Map Page 20 – 21 Life at UEL Page 23 Study Abroad Options Page 25 – 27 Academic School Profiles Page 28 – 29 Practicalities Page 30 – 31 Accommodation Page 32 Module Choices ©2011 University of East London Welcome This is an exciting time for UEL, and especially for our students. With 2012 on the horizon there is an unprecedented buzz about East London. Alongside a major regeneration programme for the region, UEL has also been transformed. Our £170 million campus development programme has brought a range of new facilities, from 24/7 multimedia libraries and state-of-the-art clinics,to purpose-built student accommodation and, for 2011, a major new sports complex. That is why I am passionate about our potential to deliver outstanding opportunities to all of our students. Opportunities for learning, for achieving, and for building the basis for your future career success. With our unique location, our record of excellence in teaching and research, the dynamism and diversity provided by our multinational student community and our outstanding graduate employment record, UEL is a university with energy and vision. I hope you’ll like what you see in this guide and that you will want to become part of our thriving community. -

Download Booklet

MONTEVERDI © Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library ???????????? Claudio Monteverdi (1567 – 1643) The Coronation of Poppea Dramma musicale in a Prologue and two acts Libretto by Giovanni Francesco Busenello, English translation by Geoffrey Dunn Prologue Fortune Barbara Walker soprano Virtue Shirley Chapman soprano Love Elizabeth Gale soprano Opera Ottone, most noble lord Tom McDonnell baritone Poppea, most noble lady, mistress of Nero, Janet Baker mezzo-soprano raised by him to the seat of empire Nero, Roman emperor Robert Ferguson tenor Ottavia, reigning empress, repudiated by Nero Katherine Pring mezzo-soprano Drusilla, lady of the court, in love with Ottone Barbara Walker soprano Seneca, philosopher, preceptor to Nero Clifford Grant bass Arnalta, aged nurse and confidante of Poppea Anne Collins mezzo-soprano Lucano, poet, intimate of Nero, nephew of Seneca Emile Belcourt tenor Valletto, page of the empress John Brecknock tenor Damigella, lady-in-waiting to the empress Iris Saunders soprano Liberto, Captain of the praetorian guard Norman Welsby baritone First soldier Robin Donald tenor Second soldier John Delaney tenor Lictor, officer of imperial justice Anthony Davey bass Pallas Athene, goddess of wisdom Shirley Chapman soprano Chorus of Sadler’s Wells Opera Orchestra of Sadler’s Wells Opera Raymond Leppard 3 compact disc one Time Page Act I 1 Sinfonia 2:55 p. 30 Prologue 2 ‘Virtue, go hide yourself away’ 7:16 p. 30 Fortune, Virtue, Love Scene 1 3 ‘Again I’m drawn here’ 8:32 p. 31 Ottone, Soldier 2, Soldier 1 4 ‘My lord, do not go yet!’ 9:54 p. 32 Poppea, Nero Scene 2 5 ‘At last my hopes have ended’ 6:38 p. -

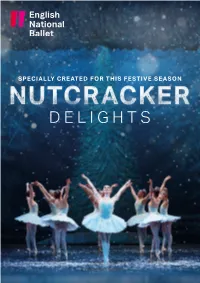

Nutcracker Delights

SPECIALLY CREATED FOR THIS FESTIVE SEASON DELIGHTS I A word from Tamara Rojo Welcome to Nutcracker Delights. I am And, finally, thank you to each of you joining us delighted that we are back on stage at the here for this festive celebration. We are so very This programme was designed for English London Coliseum and that we are once again happy to be able to share this space with you National Ballet’s planned season of Nutcracker able to share our work, live in performance, with again. I hope that you enjoy the performance. President Delights at the London Coliseum from you all. 17 December 2020 — 3 January 2021. Dame Beryl Grey DBE The extraordinary circumstances of 2020 have Chair As London moved into Tier 4 COVID-19 changed the way all of us work and live, and restrictions with the subsequent cancellation Sir Roger Carr I believe more strongly than ever in the power of all scheduled performances of Nutcracker Artistic Director of the arts to provide inspiration, shared Delights, the Company decided to film and Tamara Rojo CBE experience, hope, and solace. Tamara Rojo CBE share online, for free, a recording of this Artistic Director What a pleasure to mark our return to live specially adapted production as a gift to our Executive Director English National Ballet performance by continuing a Christmas fans at the close of our 70th Anniversary year. Patrick Harrison tradition we have held dear for 70 years. We have performed a version of Nutcracker Chief Operating Officer After a year that has been so difficult for so every year since the Company was founded, Grace Chan many, I am thrilled that we are able to bring and were determined to continue this much- Music Director some festive magic back to the stage. -

London Theatre and Theatre Breaks

LONDON THEATRE AND THEATRE BREAKS Simon Harding Theatre Breaks London London Theatre and Theatre Breaks Copyright © 2012 by Simon Harding. Contents Introduction 1. London Theatres 2. London Shows 3. London Theatre Tickets 4. Theatre Ticket Prices 5. Some Interesting Bits of Knowledge 6. Top tricks for Having a Better Time AND Saving Money 7. Getting To London 8. Getting Around London 9. Theatre Breaks - Staying Over Night 10. Pre-Theatre Dinner 11. What's On in London Now 12. Taking the Family to the Theatre 13. Anything Else 14. 2014 Theatre Break Draw Introduction How do you make sure that your trip to London’s Theatreland is the best that you could hope for? London boasts a greater array of theatre than anywhere else in the world. From the world famous musicals in the West End to the public funded theatres of the Southbank and the Royal Opera House, via the pubs and clubs of the fringe theatre scene: offering everything from burlesque to Shakespeare – and sometimes burlesque Shakespeare! On any given night, thousands of actors are entertaining hundreds of thousands of visitors and residents, in hundreds of venues. Some are one-night stands, others have been going for ten, twenty, even sixty years! Whatever may come and go, for eight performances a week, fifty-two weeks a year, London’s theatres collectively play host to the greatest show on earth! Such a bewildering array of world-class events causes its own problems. At 7:15 every night, everyone wants to pay their bill at the restaurant, at 10:30 every night everyone wants a taxi, and at 10:30 on a Sunday morning everyone expects their breakfast! So how do you make sure that your trip to London’s Theatreland is the best that you could hope for? Read On! 1 # London Theatres The West End is traditionally the heartland of London’s private sector theatres. -

ENO What's on 2017/18 Season

What’s On in 2017/18 Family feuds, lascivious lovers, breathtaking betrayals, devastating deaths and flocks of frolicking fairies. 1 Welcome to English National Opera ENO’s 2017/18 Season embraces a bold mixture of the old and new. Our audiences will have the opportunity to enjoy a whole raft of extraordinary opera, from the masterpieces of Handel and Mozart to the contemporary works of Philip Glass and Nico Muhly. We open in September with the first of our two major Verdi highlights this season: a striking new interpretation of his masterpiece Aida . We are delighted to welcome back conductor Keri-Lynn Wilson and director Phelim McDermott, who will also return later in the season to revive his iconic production of Philip Glass’s Satyagraha . It is absolutely imperative that ENO continues to develop innovative new work, and so we are thrilled to give the world premiere of Marnie , Nico Muhly’s fresh take on Winston Graham’s modern classic. Directed by Tony Award-winner Michael Mayer, this production will be the first conducted by Martyn Brabbins since his appointment as ENO Music Director in 2016. Following the success of last season’s The Pirates of Penzance , Cal McCrystal’s new production of Iolanthe will further strengthen ENO’s reputation as the premier home for the works of Gilbert and Sullivan. Moving from the hilarious to the heartbreaking, our final new production of the 2017/18 Season is a sweepingly romantic, sumptuous interpretation of La traviata from Artistic Director Daniel Kramer. For decades, ENO has enjoyed a very special relationship with the music of both Handel and Britten, and we are therefore excited to welcome back both Richard Jones’s Olivier Award-winning Rodelinda , and Robert Carsen’s magical A Midsummer Night’s Dream , and to stage a new production of The Turn of the Screw in collaboration with Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre. -

OPERA PERFORMANCES – WHAT / WHERE / WHEN 1972 to 2019

GRAHAM CLARK OPERA PERFORMANCES – WHAT / WHERE / WHEN 1972 to 2019 AUSTRIAN / GERMAN BEETHOVEN Fidelio Jacquino Glasgow - Theatre Royal - Scottish Opera 1977 7 Edinburgh - King's Theatre - Scottish Opera 1977 2 9 BERG Lulu Maler, Schwarzer Mann Paris - Théâtre du Châtelet - Orchestre National de France 1991 6 6 BERG Lulu Prinz, KaMMerdiener, Marquis Salzburg - Salzburger Festspiele - Staatskapelle Berlin 1995 / 99 8 New York - Lincoln Center - The Metropolitan Opera 2001 / 10 8 Berlin - Staatsoper iM Schiller Theater - Deutsche Staatsoper Berlin 2015 4 20 BERG Wozzeck HauptMann Paris - Salle Pleyel - Orchestre PhilharMonique de Radio France - Radio France 1989 1 New York - Lincoln Center - The Metropolitan Opera 1989 / 90 / 97 / 2001 / 05 / 06 18 Paris - Théâtre du Châtelet - Orchestre de Paris 1992 / 93 / 98 11 Berlin - Staatsoper Unter den Linden - Deutsche Staatsoper Berlin 1994 / 97 / 99 12 Chicago - Civic Opera House - Lyric Opera of Chicago 1994 8 Madrid - Teatro de la Zarzuela - Orquesta Sinfónica de Madrid 1994 5 YokohaMa - Kanagawa KenMin Hall - Deutsche Staatsoper Berlin 1997 2 London - Royal Festival Hall - PhilharMonia Orchestra London 1998 1 Milan - Teatro alla Scala 2000 5 London - Royal Opera House Covent Garden - The Royal Opera 2002 / 06 11 BirMinghaM - HippodroMe - Welsh National Opera 2009 1 Bristol - HippodroMe - Welsh National Opera 2009 1 Oxford - apollo Theatre - Welsh National Opera 2009 1 SouthaMpton - Mayflower Theatre - Welsh National Opera 2009 1 StockholM - Kungliga Operan - Royal Swedish Opera 2010 / 11 5 -

Welcome to London!

Welcome to London We are proud to be hosting the 2017 HBA European Leadership Summit in the unique and dazzling city of London. London is a 21st century city nurturing creativity and at the forefront of change and innovation. We invite you to join us in the Summit and explore London’s hidden wonders. Interesting facts about London • Biggest city in Europe • Once named “Londinium” it was established as a civilian town by the Romans around 43 AD • Globally it was the first city to have an underground railway • Has less rainfall annually than either Rome or Bordeaux • London is the home for over 100 theatres, including 50 in the West end. • Home to the iconic Houses of Parliament Arts • Tate Modern – For the modern art enthusiasts • The National Gallery – Displays a collection of over 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900. • The Guildhall Art Gallery – Ideal for those interested in Our recommendations… Victorian art. • The Royal Opera House – In the centre of London’s Covent ✓ Just a stones-throw from the HBA European Leadership Garden, here you can find world-class opera, theatre, dance Summit venue, Gibson Hall is the impressively tall Heron and classical music. Tower. Head to the 38th floor to have a cocktail or bite to eat • London Coliseum – London’s largest theatre at Sushi Samba and admire the breath-taking views of the city at night. Alternatively grab the lift for two further floors and Food spoil yourself with brunch at Duck & Waffle. If you are able to • Borough Market – London’s most renowned street food and stay for the weekend, Brick Lane is another must to visit – drink market. -

Applauding the Cultural Scene

23_748706 ch15.qxp 1/30/06 8:54 PM Page 289 Chapter 15 Applauding the Cultural Scene In This Chapter ᮣ Getting the inside scoop on London’s theater and performing arts scene ᮣ Going to the symphony, listening to chamber music, and hitting rock concerts ᮣ Seeing opera and dance performances ᮣ Finding out what’s on and getting tickets ondon is a mecca of the performing arts, offering world-class the- Later, a symphony orchestra, rock concerts, operas, modern dance, and classical ballets. In a city renowned for its theater scene, you can enjoy every kind of play or musical. Or take your pick from the city’s own Royal Opera, Royal Ballet, English National Opera, or London Symphony Orchestra. This chapter gives you the information that you need to plan your trip to include the performing arts. Getting the Inside Scoop In the United States, people think of New York City as the theater and performing arts capital. But from a global perspective, London may hold that title, based on the number of offerings and the quality of the per- formances. Of course, London didn’t attain this stature overnight. The city has been building its theatrical reputation since the Elizabethan era, when Shakespeare, Marlowe, and others were staging their plays in a SouthCOPYRIGHTED Bank theater district. A strong musical MATERIAL tradition has been in place since the 18th century. The performing arts scene, in general, helps to give London such a buzz for residents and visitors alike. Major British stars with international screen reputations regularly perform in the West End, although you’re just as likely to see a show starring someone that you’ve never heard of but who’s well known in England. -

Unusual Back in 1983, Little Did We Know Just How Unusual Some of Them Would Be

engineered solutions consultancy design fabrication installation maintenance and inspection Christmas Lights, Regent Street, London Challenging. Weird. Wonderful. Off the Wall. “Alan Jacobi and his team share a fondness for These words could be used to describe many of the projects we have been involved working on the occasional with over the last 30+ years. When we called ourselves Unusual back in 1983, little did we know just how unusual some of them would be. Needless to say, we've grown to suit crazy idea in the name of our name – at any given time we may be creating dare devil feats for prime time TV art. We have a rapport with shows, refurbishing the flying system of a century old theatre, devising solutions which Unusual and we trust the enable museums to hang unique artworks or rigging the opening and closing team implicitly – why would ceremonies of the biggest sporting events in the world. We've got our fingers in lots of we work with anyone else?” pies – entertainment, engineering, museums and galleries – as well as numerous one-off Michael Morris, projects or 'significant others', some of which are featured in this brochure. Enjoy! Co-Director, Artangel © Matthew Andrews 2016 Photo: Manuel Harlan London's Burning Festival Go Further Shanghai Chickenshed Half A Sixpence Rio 2016 www.unusual.co.uk [email protected] 01604 830083 ENTERTAINMENT Bat Out Of Hell The Musical We love theatre – it's in our blood and nothing gets us more excited than being involved with the latest “Once again, Unusual Rigging big scale musical, play or even ballet. -

London Guide Was Updated by 1L Section Entertainment 12 Representatives Ladun Omideyi, Meghan Ingrisano, and Jessica Levin in 2011

Table of Contents A very special thanks to all of the 1L Section Reps who researched and wrote this Introduction 1 Cheap Living Guides. Even in the midst of exams, the Auction, Ames, and everything Housing 2 else that consumes 1L year, they made time to make sure that their classmates get the Transportation 6 most out of their public interest summer internship experience. Have a wonderful Other Necessities 8 summer! Dining 10 - Kirsten Bermingham, OPIA Assistant Director for Administration Shopping 11 *The London Guide was updated by 1L section Entertainment 12 representatives Ladun Omideyi, Meghan Ingrisano, and Jessica Levin in 2011. Charity Fort and Congratulations! You’ve gotten a great Elizabeth Nehrling updated the Guide in 2013 public interest internship. You’re ready for the challenges and rewards of your job, but are you ready to move to, navigate, and enjoy a new city on a modest salary? It can be difficult to live cheaply in some of the world’s most expensive (and exciting) cities, so OPIA and the 1L Public Interest Section Representatives have put together a guide to give you a few tips on how to get by (and have fun) on a public interest salary. We’ll tell you how to find safe, inexpensive housing, get around in the city, eat out or in, hang out, and explore the city’s cultural offerings. In compiling these guides, we relied on numerous sources: our own experiences, law school career service offices, newspapers, the Internet, and especially Harvard Law School students. The information in Cheap Living is meant to be helpful, not authoritative.