EMILY's LIST, ) ) Plaintiff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Entire Issue in Pdf Format

JILL JOHNSTON ON FAMILY VALUES MARGE PIERCY ON BEAUTY AS PAIN SPRING 1996 $3,95 • CANADA $4.50 THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY POLITICS Has it hijackedthe women's movement? WOMEN TO WATCH IN '96 NEW MUSIC: STARK RAVING RAD WHY ANNIE (OAKLEY) GOT HER GUN 7UU70 78532 The Word 9s Spreading... Qcaj filewsfrom a Women's Perspective Women's Jrom a Perspective Or Call /ibout getting yours At Home (516) 696-99O9 SPRING 1996 VOLUME V • NUMBER TWO ON IKE ISSUES THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY features 18 COVER STORY How Orgasm Politics Has Hi j acked the Women's Movement SHEILAJEFFREYS Why has the Big O seduced so many feminists—even Ms.—into a counterrevolution from within? 22 ELECTION'96 Running Scared KAY MILLS PAGE 26 In these anxious times, will women make a difference? Only if they're on the ballot. "Let the girls up front!" 26 POP CULTURE Where Feminism Rocks MARGARET R. SARACO From riot grrrls to Rasta reggae, political music in the '90s is raw and real. 30 SELF-DEFENSE Why Annie Got Her Gun CAROLYN GAGE Annie Oakley trusted bullets more than ballots. She knew what would stop another "he-wolf." 32 PROFILE The Hot Politics of Italy's Ice Maiden PEGGY SIMPSON At 32, Irene Pivetti is the youngest speaker of the Italian Parliament hi history. PAGE 32 36 ACTIVISM Diary of a Rape-Crisis Counselor KATHERINE EBAN FINKELSTEIN Italy's "femi Newtie" Volunteer work challenged her boundaries...and her love life. 40 PORTFOLIO Not Just Another Man on a Horse ARLENE RAVEN Personal twists on public art. -

Jolene Unsoeld PDF.Indd

JOLENE UNSOELD “Un-sold” www.sos.wa.gov/legacy who ARE we? | Washington’s Kaleidoscope Jolene addresses an anxious group of employees at Hoquiam Plywood Company in 1988 as the uncertainty over timber supplies intensifies. Kathy Quigg/The Daily World Introduction: “The Meddler” imber workers in her district were mad as hell over set- asides to protect the Northern Spotted Owl. Rush Lim- Tbaugh branded her a “feminazi.” Gun-control advocates called her a flip-flopper. It was the spring of 1994 and Con- gresswoman Jolene Unsoeld of Olympia was girding for the political fight of her life. CSPAN captured her in a bitter de- bate with abortion opponents. Dick Armey, Newt Gingrich’s sidekick, was standing tall in his armadillo-skin cowboy boots, railing against the “self-indulgent conduct” of women who had been “damned careless” with their bodies. As other Republi- cans piled on, Unsoeld’s neck reddened around her trademark pearl choker. Men just don’t get it, she shot back. “Reproductive health is at the very core of a woman’s existence. If you want to be brutally frank, what it compares with is if you had health- care plans that did not cover any illness related to testicles. I “Un-sold” 3 think the women of this country are being tolerant enough to allow you men to vote on this!” Julia Butler Hansen, one of Jolene’s predecessors repre- senting Washington’s complicated 3rd Congressional District, would have loved it. Brutally frank when provoked, Julia was married to a logger and could cuss like one. -

Transcript By: Federal News Service Washington, D.C

CAMPAIGN FINANCE INSTITUTE CAMPAIGN FINANCE REFORM FORUM FRIDAY, JANUARY 14, 2005 NATIONAL PRESS CLUB WASHINGTON, D.C. PANEL TWO PARTICIPANTS: ELLEN MALCOLM, FOUNDER AND PRESIDENT, EMILY’S LIST MICHAEL J. MALBIN, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, CAMPAIGN FINANCE INSTITUTE STEPHEN WEISSMAN, ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR, CAMPAIGN FINANCE INSTITUTE, POLICY MIKE RUSSELL SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, CREATIVE RESPONSE CONCEPTS Transcript by: Federal News Service Washington, D.C. MICHAEL MALBIN: Please take your seats again. The second panel today will be about the effects of BCRA on interest groups and advocacy organizations. That section of the book will include a chapter by Clyde Wilcox from Georgetown University that will trace former soft money donors to see whether their funds have reentered the system. And just to let you know -- because this relates to a comment that was made during the past session -- the data have not been completely analyzed but seem to be showing that many of the soft money donors did not participate this time. We’ll report those complete results as they become available. Other chapters will look at the effects of BCRA on ongoing interest groups and advocacy organizations, which can operate politically through a large number of forms. For example, they can form a federal political action committee, or PAC; they can encourage members to contribute as individuals to candidates; they can contribute money from their corporate treasuries to a political party’s – they can still contribute money from the treasury to a political party’s convention committee or to an inaugural committee; they can contribute to a nonprofit issue advocacy organization or trade association that, for tax buffs, would be one that is organized under 501(c)(4), (5), or (6) under the Internal Revenue Code, or they can support a kind of political committee that has become known as a 527 committee, named after that section of the Internal Revenue Code for political committees. -

1992-93 1993-94

1992-93 1993-94 Institute of Politics John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University PROCEEDINGS Institute of Politics 1992-93 1993-94 John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University FOREWORD The Institute of Politics participates in the democratic process through the many and varied programs it sponsors: a program for fellows, a program for undergraduate and graduate students, training programs for elected officials, conferences and seminars and a public events series of speakers and panel discussions in the Foriun of Public Affairs of the John F. Kermedy School of Government. The program for fellows brings individuals from the world of politics and the media to the Institute for a semester of reassessment and personal enrichment. The program for students encourages them to become involved in the practical aspects of politics and affords them an opportunity to participate in both planning and implementing Institute programs. This edition oi Proceedings, the fourteenth, covers academic years 1992-93 and 1993- 94. The Readings section provides a glimpse at some of the actors involved and some of the political issues—domestic and international—discussed at the Institute during these twenty-four months. The Programs section presents a roster of Institute activities and includes details of many aspects of the student program: study groups and twice- weekly suppers, Heffernan visiting fellows, summer internships and research grants, the quarterly magazine Harvard Political Review, awards for undergraduate political writing, political debates, brown bag lunches, and numerous special projects. Also provided is information on the program for fellows, conferences and seminars, and a list of events held in the Foriun. -

A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The

WOMEN SPEAKERS IN AMERICA: IS ANYONE LISTENING? A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By Christine K. Jahnke, B.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. March 26, 2012 WOMEN SPEAKERS IN AMERICA: IS ANYONE LISTENING? Christine K. Jahnke, B.A. Mentor: Susan Deller Ross, J.D. ABSTRACT Women comprise a majority of the population in the United States but remain a minority voice. The male voice dominates in the corridors of power, drowning out women in corporate boardrooms, the halls of Congress, and the news media. Thus, women lack an equal say in important decision making and agenda setting. Women who have attempted to exercise the right of free speech have often been ignored, silenced, and/or maligned. This raises a question: To what extent is the lack of an equal public voice a significant factor in preventing women from obtaining more equitable levels of leadership? This thesis will explore how women have fared in their struggle to be heard, the contributions made by women speakers, and the necessity of including a female perspective in the public dialogue. This examination of women speakers begins with an overview of how the right to free speech was denied long before – and long after – our nation was founded. It will look at the cultural expectation of silence that prevented women from playing a role in public life in colonial America up until the mid 1800’s. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the origmal or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter free, vdnle others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversety affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b%inning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographicaUy in this copy. ISgher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for aity photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & HowcQ Ln&nnabon Company 300 Noith Zed) Road, Ann Arbor NQ 4S106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 PERFORMING POLITICS: A THEATRE-BASED ANALYSIS OF THE 1996 NATIONAL NOMINATING CONVENTIONS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by John Brooks Lawton m , A.B., M.A. -

The Forgotten Few: Campaign Finance Reform and Its Impact on Minority and Female Candidates, 22 B.C

Boston College Third World Law Journal Volume 22 | Issue 1 Article 4 1-1-2002 The orF gotten Few: Campaign Finance Reform and Its Impact on Minority and Female Candidates Jason P. Conti Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/twlj Part of the Election Law Commons Recommended Citation Jason P. Conti, The Forgotten Few: Campaign Finance Reform and Its Impact on Minority and Female Candidates, 22 B.C. Third World L.J. 99 (2002), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/twlj/vol22/ iss1/4 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Third World Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORGOTTEN FEW: CAMPAIGN FINANCE REFORM AND ITS IMPACT ON MINORITY AND FEMALE CANDIDATES JASON P. CONTI* Abstract: Campaign finance reform attracts intense political, academic, and media attention. The debate swirling around the McCain-Feingold legislation in 2001 is evidence of the power of the issue. Despite the intensity of the spotlight, commentators and politicians often overlook an important element of any proposed reform: diversity. This Note explores campaign finance reform from an under-explored angle: the impact proposed reforms would have on minority and female candidates. This Note explores the woefully inadequate diversity of representation in elective office and critiques numerous proposals for change from the perspective of a prospective minority or female candidate. This Note concludes that in order for the diversity of those holding elective office to better reflect the diversity of the nation as a whole, reformers must take the concerns of minority and female candidates into account and must institute publicly funded campaigns. -

The Politics of Endorsing Hillary Clinton in the 2008 Democratic Presidential Primary

Primary Feminism: The Politics of Endorsing Hillary Clinton in the 2008 Democratic Presidential Primary By Kayla Calkin B.A. 2007, Wellesley College A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts August 31, 2011 Thesis Directed by Cynthia Harrison Associate Professor of History, Women’s Studies, and Public Policy © Copyright 2011 by Kayla Calkin All rights reserved ii Dedication The author wishes to dedicate this thesis to her campaign host mother, friend, advisor, and heroine Sandra Gillis. iii Acknowledgements The author wishes to acknowledge the help she received while writing this paper. Thanks to all the women I interviewed who gave up their time to speak with me. Thanks to Professor Reverby for lending a second ear to this paper, and for four years of help at Wellesley. Thanks to Professor Harrison for a year of emails, questions, drafts and advice. Thanks to The George Washington University for providing with me the GTA Fellowship. And finally thanks to my parents for raising a feminist daughter! iv Abstract of Thesis Primary Feminism: The Politics of Endorsing Hillary Clinton in the 2008 Democratic Presidential Primary This thesis examines five feminist organizations involved in the 2008 Democratic Presidential Primary including the National Organization for Women (NOW), the National Women’s Political Caucus (NWPC), Women’s Campaign Forum (WCF), Emily’s List, and NARAL. Did these feminist organizations endorse in the primary elections? Whom did they endorse and why? What were their goals and how did they come to their decisions? What was the reaction from the press? Public? Their members? Did they succeed in the aims of their endorsement? This thesis includes first a look at the theories surrounding women’s voting patterns. -

Assembling, Amplifying, and Ascending Recent Trends Among Women in Congress, 1977–2006

Assembling, Amplifying, and Ascending recent trends among women in congress, 1977–2006 The fourth wave of women to enter Congress–from 1977 to 2006– was by far the largest and most diverse group. These 134 women accounted for more than half (58 percent) of all the women who have served in the history of Congress. In the House, the women formed a Congresswomen’s Caucus (later called the Congressional Caucus for Women’s Issues), to publicize legislative initiatives that were important to women. By honing their message and by cultivating political action groups to support female candidates, women became more powerful. Most important, as the numbers of Congresswomen increased and their legislative inter- ests expanded, women accrued the seniority and influence to advance into the ranks of leadership. Despite such achievements, women in Congress historically account for a only a small fraction—about 2 percent—of the approximately 12,000 individuals who have served in the U.S. Congress since 1789, although recent trends suggest that the presence of women in Congress will continue to increase. Based on gains principally in the House of Representatives, each of the 13 Congresses since 1981 has had a record number of women Members. (From left) Marilyn Lloyd, Tennessee; Martha Keys, Kansas; Patricia Schroeder, Colorado; Margaret Heckler, Massachusetts; Virginia Smith, Nebraska; Helen Meyner, New Jersey; and Marjorie Holt, Maryland, in 1978 in the Congresswomen’s Suite in the Capitol—now known as the Lindy Claiborne Boggs Congressional Reading Room. Schroeder and Heckler co-chaired the Congresswomen’s Caucus, which met here in its early years. -

The Politics of Listlessness: the Democrats Since 1981

The Politics of Listlessness: The Democrats since 1981 October 8, 2019 Chapter 9 of Daniel Schlozman and Sam Rosenfeld, The Hollow Parties In September 1981, a hundred leading Democratic elected officials from across a beleaguered party convened for a Democratic National Strategy Council, aiming to formulate Democrats’ response to Reaganism. Alan Cranston of California, the Senate Democratic Whip, chaired “A Conversation among Democrats.” The questions prepared for that session could be repeated, nearly verbatim, after every electoral setback for Democrats down through 2016. They portend the paths followed, and also the paths left untrod, in the decades since. “If our party is a coalition, unlike the Republicans who tend to represent a single group, what are the common denominators, transcending regional differences and local interests, which make us a National Party?... The Republicans cannot, and will not, represent the needs and hopes of middle and lower income Americans, as we are committed to do. Yet numbers of these Americans voted Republican in 1978 and 1980. How have we failed to make clear that the Democratic Party represents the true interests of these and other Americans among our true constituencies?... To endure, a Party must look to the future as well as stay true to its past. What problems have we as a Party failed to face up to? Where will the next two decades take us and what are the principle (sic.) new challenges that we must address?”1 Incipient in each question is the goal of a party that would bring together its many constituencies in shared vision and common purpose—but also the recognition of the forces that would militate against that goal. -

This Isn't Your Mom's Tupperware Party

THIS ISN’T YOUR MOM’S TUPPERWARE PARTY: HOW EMILY’S LIST CHANGED THE AMERICAN POLITICAL LANDSCAPE By JAMIE PAMELIA PIMLOTT A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2007 1 © 2007 Jamie Pamelia Pimlott 2 For Pamie: tee hee, llama, emu, snort! 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In no way would this dissertation have been completed without the support and love of a great number of people. First I’d like to thank my chair, Lawrence C. Dodd. Without his support and belief in me from Day One I would not have continued with my studies. I will always cherish the time spent with him talking about scholarship, politics, and life. Little did I know that having him as an advisor would be such a wonderful intellectual experience. I only hope that one day I will be able to offer the same kind of support and intellectual stimulation to my own students. I would also like to thank Leslie Anderson, who pulled me aside one day in after class in 2002 and said, “Why aren’t you in the Ph.D. program?” Dan Smith’s support and advice became critical early on in my search of the dissertation topic—I first began researching EMILY’s List in his Campaign Finance course. He also provided a wonderful sounding board as I struggled to find a job in D.C. and work through the juggernaut of campaign finance legislation. During a discussion over a topic for an Independent study course, Lynn Leverty, one of my first graduate school teachers (during Grad School Part I) said to me, “This topic is dissertation material!” From those first few courses—the Field Seminar and APD—and throughout this project Beth Rosenson provided an excellent blend of criticism and encouragement. -

George Soros, a Key Donor Who Pledged $10 Million in Soft Money to ACT As

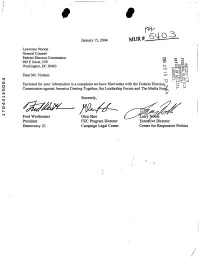

-- I .. I 8 I January 15, ‘2004 Lawrence Norton General Counsel Federal Election Commission ul-d ca 999 E Street, NW J=- Washington, DC 20463 Dear Mr. Norton:. 9 Enclosed for your information is a complaint we have filed today with the Federal Election r.3 Commission against America Coming Together, the Leadership Forum and The Media Fur$, c Sincerely, Fred Wertheimer Glen Shor President FEC Program Director Democracy 21 Campaign Legal Center Center for Responsive Politics / I BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION Democracy 21 1825 I Street, NW, Suite 400 Washington, DC 20006 202-429-2008 % :. .. Campaign Legal Center . A- d 1101 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 330 cn .Washington,DC 20036 202-736-2200 Center for Responsive Politics 1101 14'" Street, NW, Suite 1030 . Washington, DC 20005 202-857-0044 V. America Coming Together 888 16th Street, NW Washington, DC 20006 202-974-8360 The Leadership Forum 4123 South 36thStreet Arlington, Virginia 22206 \ The Media Fund 1120 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 1100 Washington, DC 20036 202-974-8320 COMPLAINT 2 1. In March, 2002, Congress enacted the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (BCRA) in order to stop the injection of soft money into federal elections. The relevant provisions of BCRA were upheld by the Supreme Court in McConneZZ v. FEC,540 U.S. (slip op. December 10,2003). 2. Since the enactment of BCRA, a number of party and political operatives, and former soft money donors, have been engaged in efforts to circumvent BCRA by planning and implementing new schemes to use soft money to influence the 2004 presidential and congressional elections.