White Picket Fence” Around Human Cognition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bloomsbury Scientists Ii Iii

i Bloomsbury Scientists ii iii Bloomsbury Scientists Science and Art in the Wake of Darwin Michael Boulter iv First published in 2017 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.ucl.ac.uk/ ucl- press Text © Michael Boulter, 2017 Images courtesy of Michael Boulter, 2017 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Non-derivative 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Michael Boulter, Bloomsbury Scientists. London, UCL Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787350045 Further details about Creative Commons licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 006- 9 (hbk) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 005- 2 (pbk) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 004- 5 (PDF) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 007- 6 (epub) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 008- 3 (mobi) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 009- 0 (html) DOI: https:// doi.org/ 10.14324/ 111.9781787350045 v In memory of W. G. Chaloner FRS, 1928– 2016, lecturer in palaeobotany at UCL, 1956– 72 vi vii Acknowledgements My old writing style was strongly controlled by the measured precision of my scientific discipline, evolutionary biology. It was a habit that I tried to break while working on this project, with its speculations and opinions, let alone dubious data. But my old practices of scientific rigour intentionally stopped personalities and feeling showing through. -

Transformations of Lamarckism Vienna Series in Theoretical Biology Gerd B

Transformations of Lamarckism Vienna Series in Theoretical Biology Gerd B. M ü ller, G ü nter P. Wagner, and Werner Callebaut, editors The Evolution of Cognition , edited by Cecilia Heyes and Ludwig Huber, 2000 Origination of Organismal Form: Beyond the Gene in Development and Evolutionary Biology , edited by Gerd B. M ü ller and Stuart A. Newman, 2003 Environment, Development, and Evolution: Toward a Synthesis , edited by Brian K. Hall, Roy D. Pearson, and Gerd B. M ü ller, 2004 Evolution of Communication Systems: A Comparative Approach , edited by D. Kimbrough Oller and Ulrike Griebel, 2004 Modularity: Understanding the Development and Evolution of Natural Complex Systems , edited by Werner Callebaut and Diego Rasskin-Gutman, 2005 Compositional Evolution: The Impact of Sex, Symbiosis, and Modularity on the Gradualist Framework of Evolution , by Richard A. Watson, 2006 Biological Emergences: Evolution by Natural Experiment , by Robert G. B. Reid, 2007 Modeling Biology: Structure, Behaviors, Evolution , edited by Manfred D. Laubichler and Gerd B. M ü ller, 2007 Evolution of Communicative Flexibility: Complexity, Creativity, and Adaptability in Human and Animal Communication , edited by Kimbrough D. Oller and Ulrike Griebel, 2008 Functions in Biological and Artifi cial Worlds: Comparative Philosophical Perspectives , edited by Ulrich Krohs and Peter Kroes, 2009 Cognitive Biology: Evolutionary and Developmental Perspectives on Mind, Brain, and Behavior , edited by Luca Tommasi, Mary A. Peterson, and Lynn Nadel, 2009 Innovation in Cultural Systems: Contributions from Evolutionary Anthropology , edited by Michael J. O ’ Brien and Stephen J. Shennan, 2010 The Major Transitions in Evolution Revisited , edited by Brett Calcott and Kim Sterelny, 2011 Transformations of Lamarckism: From Subtle Fluids to Molecular Biology , edited by Snait B. -

King's Research Portal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by King's Research Portal King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1016/j.shpsc.2017.07.002 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Manias, C. (2017). Progress in Life’s History: Linking Darwinism and Palaeontology in Britain, 1860-1914. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2017.07.002 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Illuminating Our World: an Essay on the Unraveling of the Species Problem, with Assistance from a Barnacle and a Goose

Humanities 2012, 1, 145–165; doi:10.3390/h1030145 OPEN ACCESS humanities ISSN 2076-0787 www.mdpi.com/journal/humanities Article Illuminating our World: An Essay on the Unraveling of the Species Problem, with Assistance from a Barnacle and a Goose John Buckeridge * and Rob Watts Earth & Oceanic Systems Group, RMIT University, Melbourne, GPO Box 2476, Australia * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-399-252-009. Received: 18 July 2012; in revised form: 27 September 2012 / Accepted: 8 October 2012 / Published: 15 October 2012 Abstract: In order to plan for the future, we must understand the past. This paper investigates the manner in which both naturalists and the wider community view one of the most intriguing of all questions: what makes a species special? Consideration is given to the essentialist view—a rigid perspective and ancient, Aristotelian perspective—that all organisms are fixed in form and nature. In the middle of the 19th century, Charles Darwin changed this by showing that species are indeed mutable, even humans. Advances in genetics have reinforced the unbroken continuum between taxa, a feature long understood by palaeontologists; but irrespective of this, we have persisted in utilizing the ‗species concept‘—a mechanism employed primarily to understand and to manipulate the world around us. The vehicles used to illustrate this journey in perception are the barnacle goose (a bird), and the goose barnacle (a crustacean). The journey of these two has been entwined since antiquity—in folklore, religion, diet and even science. Keywords: species concept; organic evolution; history of biology; goose barnacles; barnacle geese; Aristotle; Charles Darwin; Linnaeus 1. -

A Short History of Our Department

LONDON’S GLOBAL UNIVERSITY Research Department of Genetics, Evolution and Environment A short history of our department The department was formed during the recent reorganisation of the Faculty of Life Sciences that brought together scientists with shared interests in biology, genetics, environmental and evolutionary biology who had previously been scattered among a variety of distinct departments. It traces its origins to the now extinct Department of Comparative Anatomy, founded in 1826, and the first in Britain to offer a Zoology degree. It also incorporates the Galton Laboratory, the first institution in the world to study human genetics as a science and previously named Departments of Biology, Botany, Genetics & Biometry, Microbiology and Zoology. Some great figures of the past have been associated with the Department - whose main building stands on the site of Charles Darwin's home, on Gower Street. They include Robert Grant (who taught Darwin in Edinburgh and whose extraordinary collection of animal specimens are now held in the Grant Museum), Sir Francis Galton (Darwin's cousin, and the founder of the modern study of human genetics and - less creditably - of eugenics, whose legacy helped establish the Galton Laboratory). Its early members included Karl Pearson and R A Fisher (jointly the founders of modern statistical science), J B S Haldane (the eccentric genius who worked on submarine escape methods and helped to place the theory of evolution on a mathematical basis), and F R Weldon, who carried out the earliest experimental studies on natural selection in action. Later, the Nobel Prize winner, Sir Peter Medawar, who worked out the genetics of tissue recognition and was central to the development of organ transplantation. -

History of Genetics Book Collection Catalogue

History of Genetics Book Collection Catalogue Below is a list of the History of Genetics Book Collection held at the John Innes Centre, Norwich, UK. For all enquires please contact Mike Ambrose [email protected] +44(0)1603 450630 Collection List Symposium der Deutschen Gesellschaft fur Hygiene und Mikrobiologie Stuttgart Gustav Fischer 1978 A69516944 BOOK-HG HG œ.00 15/10/1996 5th international congress on tropical agriculture 28-31 July 1930 Brussels Imprimerie Industrielle et Finangiere 1930 A6645004483 œ.00 30/3/1994 7th International Chromosome Conference Oxford Oxford 1980 A32887511 BOOK-HG HG œ.00 20/2/1991 7th International Chromosome Conference Oxford Oxford 1980 A44688257 BOOK-HG HG œ.00 26/6/1992 17th international agricultural congress 1937 1937 A6646004482 œ.00 30/3/1994 19th century science a selection of original texts 155111165910402 œ14.95 13/2/2001 150 years of the State Nikitsky Botanical Garden bollection of scientific papers. vol.37 Moscow "Kolos" 1964 A41781244 BOOK-HG HG œ.00 15/10/1996 Haldane John Burdon Sanderson 1892-1964 A banned broadcast and other essays London Chatto and Windus 1946 A10697655 BOOK-HG HG œ.00 15/10/1996 Matsuura Hajime A bibliographical monograph on plant genetics (genic analysis) 1900-1929 Sapporo Hokkaido Imperial University 1933 A47059786 BOOK-HG HG œ.00 15/10/1996 Hoppe Alfred John A bibliography of the writings of Samuel Butler (author of "erewhon") and of writings about him with some letters from Samuel Butler to the Rev. F. G. Fleay, now first published London The Bookman's Journal -

The Darwinian Revolution: Rethinking Its Meaning and Significance

The Darwinian revolution: Rethinking its meaning and significance Michael Ruse1 Department of Philosophy, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306 The Darwinian revolution is generally taken to be one of the key (a perhaps undeserved) reputation of a 3-h sermon by a Pres- events in the history of Western science. In recent years, however, byterian minister on a wet Sunday in Scotland. the very notion of a scientific revolution has come under attack, Against this, however, one can point out that the history of and in the specific case of Charles Darwin and his Origin of Species science as a professional discipline is little more than 50 years old there are serious questions about the nature of the change (if there and that you have to start somewhere. In the case of Darwin, was such) and the specifically Darwinian input. This article consid- even 30 years ago there was no real synthesis. The tragedy would ers these issues by addressing these questions: Was there a have been if historians of science had stopped there and gone no Darwinian revolution? That is, was there a revolution at all? Was further. But this is clearly not true. In the past 30 years or more, there a Darwinian revolution? That is, what was the specific staying just with the history of evolutionary thinking, there has contribution of Charles Darwin? Was there a Darwinian revolu- been a huge amount of work on people before and after Darwin, tion? That is, what was the conceptual nature of what occurred on and on his contemporaries like Thomas Henry Huxley [for and around the publication of the Origin? I argue that there was instance, Desmond (4)]. -

AMNH Digital Library

#,<s^ s'jji"^ / b V«<r '^n iti«s '^v^ k-^ \ »^*i>s>«4lk>j itnw jL-»>' f'TOMi v»- ^oaSW ' fe'3*'*>«l. Voyage through the heart of the Highlands. Discover a seldom-seen Scotland. There's the Scotland mostpeople get to see and there's the Scotlandfew get to see. Now you can experience the authentic Highlands exclusively with Lindblad Expeditions on a unique journey by ship and rail. Heart of the Highlands traverses Scotland in yacht style via lakes, lochs and the scenic Caledonian Canal — from the North Sea to the Atlantic. As the name implies, you travel through the hauntingly dramatic region of rolling hOs, vast sweeps of moorland, lochs and stately castles that means "Scotland" for most connoisseurs. The yacht-scale of the deluxe 54-guest Lord of the G/^/zy navigates the many size-limiting lochs Scotland is famous for — from Neptune's Staircase to the infamous Loch Ness — enabling us to see the Highlands from a remarkable vantage point few have experienced. With teak decks, richly waxed interiors, fine cuisine and personal service, the Lord of the 6"/^;^ provides a satisfying experience in and of itself. Add one of the world's classic touring trains. The Royal Scotsman, to your experience for a return to Edwardian era levels of travel and a modern exercise in comfort — with gourmet cuisine, fine wines, elegant accommodations and above all, exceptional scenery. The combination of Lord of the Glens and the Royal Scotsman makes this a rare, rewarding and completely new way to experience one of the most intimate of all the possible "Scotlands." We look forward to discovering the hidden Highlands with you! Lindblad Sven-OlofLindblad Expeditions Visit our web site at www.expeditions.com/2explore or complete the attached reply card to enter to win a free trip for two to any destination in our new brochure: Explorations 2002-2003. -

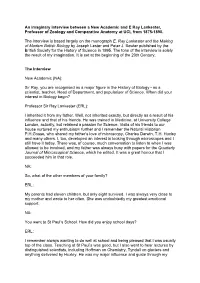

An Imaginary Interview Between a New Academic and E Ray Lankester, Professor of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy at UCL from 1875-1890

An imaginary interview between a New Academic and E Ray Lankester, Professor of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy at UCL from 1875-1890. The interview is based largely on the monograph E. Ray Lankester and the Making of Modern British Biology by Joseph Lester and Peter J. Bowler published by the British Society for the History of Science in 1995. The tone of the interview is solely the result of my imagination. It is set at the beginning of the 20th Century. The Interview New Academic (NA): Sir Ray, you are recognised as a major figure in the History of Biology - as a scientist, teacher, Head of Department, and populariser of Science. When did your interest in Biology begin? Professor Sir Ray Lankester (ERL): I inherited it from my father. Well, not inherited exactly, but directly as a result of his influence and that of his friends. He was trained in Medicine, at University College London, actually, but retained a passion for Science. Visits of his friends to our house nurtured my enthusiasm further and I remember the Natural Historian P.H.Gosse, who shared my father’s love of microscopy, Charles Darwin, T.H. Huxley and many others. I, too, developed an interest in looking through microscopes and I still have it today. There was, of course, much conversation to listen to when I was allowed to be involved, and my father was always busy with papers for the Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, which he edited. It was a great honour that I succeeded him in that role. NA: So, what of the other members of your family? ERL: My parents had eleven children, but only eight survived. -

Lamarck, and Neo-Lamarckianism

LAMARCK, AND NEO-LAMARCKIANISM. BY PROF. A. S. PACKARD. WHO WAS LAMARCK, and what work did he accomplish ? Was he merely a compiler like Buffon or the author of the Vestiges of Creation^ If we look for an answer in Darwin's im- mortal work The Origin of Species, we shall find that for once this otherwise invariably candid writer, so prone to give the fullest credit for aid to his contemporaries, in referring to his great French predecessor, whose eminence as a philosopher he did not at all ap- preciate, sets aside his theories and speaks of "the views and erroneous grounds of opinion of Lamarck " as having been largely anticipated by his grandfather Erasmus Darwin. It is question- able whether Darwin ever carefully read through Lamarck's Zoologie Philosophique, or the other writings of the French zoologist. We have heard a young but distinguished English zoologist call La- marck's "a bad book," probably meaning that it was not sound from the Neo-Darwinian point of view. Ray Lankester writes of Lamarck in Nattire, as if the doctrine of the inheritance of acquired habits were the sole, or at least the most characteristic, contribu- tion Lamarck had made to the theory of descent. It is evident that these English writers have not carefully read all that Lamarck has written, while they do not give him that credit for the clearness and fulness of his views, which Haeckel and others in Germany have done. It should be here said that Lamarck's lucubrations on chemical and physical as well as physiological subjects are worthless, and his lack of caution in publishing them is deplorable. -

Darwin. a Reader's Guide

OCCASIONAL PAPERS OF THE CALIFORNIA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES No. 155 February 12, 2009 DARWIN A READER’S GUIDE Michael T. Ghiselin DARWIN: A READER’S GUIDE Michael T. Ghiselin California Academy of Sciences California Academy of Sciences San Francisco, California, USA 2009 SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS Alan E. Leviton, Ph.D., Editor Hallie Brignall, M.A., Managing Editor Gary C. Williams, Ph.D., Associate Editor Michael T. Ghiselin, Ph.D., Associate Editor Michele L. Aldrich, Ph.D., Consulting Editor Copyright © 2009 by the California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Drive, San Francisco, California 94118 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISSN 0068-5461 Printed in the United States of America Allen Press, Lawrence, Kansas 66044 Table of Contents Preface and acknowledgments . .5 Introduction . .7 Darwin’s Life and Works . .9 Journal of Researches (1839) . .11 Geological Observations on South America (1846) . .13 The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs (1842) . .14 Geological Observations on the Volcanic Islands…. (1844) . .14 A Monograph on the Sub-Class Cirripedia, With Figures of All the Species…. (1852-1855) . .15 On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (1859) . .16 On the Various Contrivances by which British and Foreign Orchids are Fertilised by Insects, and on the Good Effects of Intercrossing (1863) . .23 The Different Forms of Flowers on Plants of the Same Species (1877) . -

An 2-Macroglobulin-Like Protein Is the Cue to Gregarious Settlement of The

An ␣2-macroglobulin-like protein is the cue to gregarious settlement of the barnacle Balanus amphitrite Catherine Dreanno*, Kiyotaka Matsumura†‡§, Naoshi Dohmae¶, Koji Takioʈ, Hiroshi Hirota§, Richard R. Kirby**††, and Anthony S. Clare*†† *School of Marine Science and Technology, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU, United Kingdom; †Central Research Institute of Electric Power Industry, Abiko, Chiba 270-1194, Japan; ‡Marine Biological Association, Citadel Hill, Plymouth PL1 2PB, United Kingdom; §RIKEN Genomic Sciences Center, Yokohama 230-0045, Japan; ¶RIKEN, Wako-shi, Saitama 351-0198, Japan; ʈRIKEN Spring-8 Center, Harima Institute, Sayo, Hyogo 679-5148, Japan; and **School of Biological Sciences, University of Plymouth, Plymouth PL4 8AA, United Kingdom Edited by Mimi A. R. Koehl, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved August 9, 2006 (received for review April 5, 2006) Many benthic marine invertebrates, like barnacles, have a plank- boiling, was a polymorphic system of closely related, water- tonic larval stage whose primary purpose is dispersal. How these soluble glycoproteins. The cue was named ‘‘arthropodin’’ (6, 7) species colonize suitable substrata is fundamental to understand- because of its physicochemical similarity to insect cuticular ing their evolution, population biology, and wider community protein (8). However, progress toward identifying arthropodin dynamics. Unlike larval dispersal, settlement occurs on a relatively was hampered by the short settlement season of S. balanoides small spatial scale and involves larval behavior in response to and thus the limited availability of larvae for settlement assays. physical and chemical characteristics of the substratum. Biogenic In only a few instances has a complete characterization of a chemical cues have been implicated in this process.