Illuminating Our World: an Essay on the Unraveling of the Species Problem, with Assistance from a Barnacle and a Goose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bloomsbury Scientists Ii Iii

i Bloomsbury Scientists ii iii Bloomsbury Scientists Science and Art in the Wake of Darwin Michael Boulter iv First published in 2017 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.ucl.ac.uk/ ucl- press Text © Michael Boulter, 2017 Images courtesy of Michael Boulter, 2017 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Non-derivative 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Michael Boulter, Bloomsbury Scientists. London, UCL Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787350045 Further details about Creative Commons licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 006- 9 (hbk) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 005- 2 (pbk) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 004- 5 (PDF) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 007- 6 (epub) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 008- 3 (mobi) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 009- 0 (html) DOI: https:// doi.org/ 10.14324/ 111.9781787350045 v In memory of W. G. Chaloner FRS, 1928– 2016, lecturer in palaeobotany at UCL, 1956– 72 vi vii Acknowledgements My old writing style was strongly controlled by the measured precision of my scientific discipline, evolutionary biology. It was a habit that I tried to break while working on this project, with its speculations and opinions, let alone dubious data. But my old practices of scientific rigour intentionally stopped personalities and feeling showing through. -

Transformations of Lamarckism Vienna Series in Theoretical Biology Gerd B

Transformations of Lamarckism Vienna Series in Theoretical Biology Gerd B. M ü ller, G ü nter P. Wagner, and Werner Callebaut, editors The Evolution of Cognition , edited by Cecilia Heyes and Ludwig Huber, 2000 Origination of Organismal Form: Beyond the Gene in Development and Evolutionary Biology , edited by Gerd B. M ü ller and Stuart A. Newman, 2003 Environment, Development, and Evolution: Toward a Synthesis , edited by Brian K. Hall, Roy D. Pearson, and Gerd B. M ü ller, 2004 Evolution of Communication Systems: A Comparative Approach , edited by D. Kimbrough Oller and Ulrike Griebel, 2004 Modularity: Understanding the Development and Evolution of Natural Complex Systems , edited by Werner Callebaut and Diego Rasskin-Gutman, 2005 Compositional Evolution: The Impact of Sex, Symbiosis, and Modularity on the Gradualist Framework of Evolution , by Richard A. Watson, 2006 Biological Emergences: Evolution by Natural Experiment , by Robert G. B. Reid, 2007 Modeling Biology: Structure, Behaviors, Evolution , edited by Manfred D. Laubichler and Gerd B. M ü ller, 2007 Evolution of Communicative Flexibility: Complexity, Creativity, and Adaptability in Human and Animal Communication , edited by Kimbrough D. Oller and Ulrike Griebel, 2008 Functions in Biological and Artifi cial Worlds: Comparative Philosophical Perspectives , edited by Ulrich Krohs and Peter Kroes, 2009 Cognitive Biology: Evolutionary and Developmental Perspectives on Mind, Brain, and Behavior , edited by Luca Tommasi, Mary A. Peterson, and Lynn Nadel, 2009 Innovation in Cultural Systems: Contributions from Evolutionary Anthropology , edited by Michael J. O ’ Brien and Stephen J. Shennan, 2010 The Major Transitions in Evolution Revisited , edited by Brett Calcott and Kim Sterelny, 2011 Transformations of Lamarckism: From Subtle Fluids to Molecular Biology , edited by Snait B. -

(Cirripedia : Thoracica) Over the Body of a Sea Snake, Laticauda Title Semifasciata (Reinwardt), from the Kii Peninsula, Southwestern Japan

Distribution of Two Species of Conchoderma (Cirripedia : Thoracica) over the Body of a Sea Snake, Laticauda Title semifasciata (Reinwardt), from the Kii Peninsula, Southwestern Japan Yamato, Shigeyuki; Yusa, Yoichi; Tanase, Hidetomo; Tanase, Author(s) Hidetomo PUBLICATIONS OF THE SETO MARINE BIOLOGICAL Citation LABORATORY (1996), 37(3-6): 337-343 Issue Date 1996-12-25 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/176259 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Pub!. Seto Mar. Bioi. Lab., 37(3/6): 337-343, 1996 337 Distribution of Two Species of Conchoderma (Cirripedia: Thoracica) over the Body of a Sea Snake, Laticauda semifasciata (Reinwardt), from the Kii Peninsula, Southwestern Japan SHIGEYUKI YAMATO, YOICHI YUSA and HIDETOMO TANASE Seto Marine Biological Laboratory, Kyoto University, Shirahama, Wakayama 649-22, Japan Abstract Two species of Conchoderma were found on a sea snake, Laticauda semifas ciata (Reinwardt), collected on the west coast of the Kii Peninsula. A total of 223 individuals of C. virgatum and 6 of C. hunteri in 19 clumps were attached to the snake's body. The barnacles ranged in size from 1.4 mm (cypris larvae) to 18.2 mm in capitulum length in C. virgatum, and from 10.7 to 14.4 mm in C. hunteri. The size of the smallest gravid individuals in both species was between 10 and 11 mm. The distribution of C. virgatum on the snake was non-random both longitudinally and dorso-ventrally, with more barnacles in the posterior region and on the ventral side of the snake, respectively. The proportion of gravid individuals increased towards the tail. -

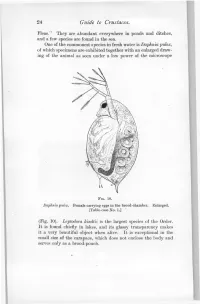

24 Guide to Crustacea

24 Guide to Crustacea. Fleas." They are abundant everywhere in ponds and ditches, and a few species are found in the sea. One of the commonest species in fresh water is Daphnia pulex, of which specimens are exhibited together with an enlarged draw- ing of the animal as seen under a low power of the microscope FIG. 10. Daphnia pulex. Female carrying eggs in the brood-chamber. Enlarged. [Table-case No. 1.] (Fig. 10). Leptodora kindtii is the largest species of the Order. It is found chiefly in lakes, and its glassy transparency makes it a very beautiful object when alive. It is exceptional in the small size of the carapace, which does not enclose the body and serves only as a brood-pouch. Ostracoda. 25 Sub-class II.—OSTRACODA. (Table-ease No. 1.) The number of somites, as indicated by the appendages, is smaller than in any other Crustacea, there being, at most, only two pairs of trunk-limbs behind those belonging to the head- region. The carapace forms a bivalved shell completely en- closing the body and limbs. There is a large, and often leg-like, palp on the mandible. The antennules and antennae are used for creeping or swimming. The Ostracoda (Fig. 10) are for the most part extremely minute animals, and only one or two of the larger species can be exhibited. They occur abundantly in fresh water and in FIG. 11. Shells of Ostracoda, seen from the side. A. Philomedes brenda (Myodocopa) ; B. Cypris fuscata (Podocopa); ('. Cythereis ornata (Podocopa): all much enlarged, n., Notch characteristic of the Myodocopa; e., the median eye ; a., mark of attachment of the muscle connecting the two valves of the shell. -

Balanus Glandula Class: Multicrustacea, Hexanauplia, Thecostraca, Cirripedia

Phylum: Arthropoda, Crustacea Balanus glandula Class: Multicrustacea, Hexanauplia, Thecostraca, Cirripedia Order: Thoracica, Sessilia, Balanomorpha Acorn barnacle Family: Balanoidea, Balanidae, Balaninae Description (the plate overlapping plate edges) and radii Size: Up to 3 cm in diameter, but usually (the plate edge marked off from the parietes less than 1.5 cm (Ricketts and Calvin 1971; by a definite change in direction of growth Kozloff 1993). lines) (Fig. 3b) (Newman 2007). The plates Color: Shell usually white, often irregular themselves include the carina, the carinola- and color varies with state of erosion. Cirri teral plates and the compound rostrum (Fig. are black and white (see Plate 11, Kozloff 3). 1993). Opercular Valves: Valves consist of General Morphology: Members of the Cirri- two pairs of movable plates inside the wall, pedia, or barnacles, can be recognized by which close the aperture: the tergum and the their feathery thoracic limbs (called cirri) that scutum (Figs. 3a, 4, 5). are used for feeding. There are six pairs of Scuta: The scuta have pits on cirri in B. glandula (Fig. 1). Sessile barna- either side of a short adductor ridge (Fig. 5), cles are surrounded by a shell that is com- fine growth ridges, and a prominent articular posed of a flat basis attached to the sub- ridge. stratum, a wall formed by several articulated Terga: The terga are the upper, plates (six in Balanus species, Fig. 3) and smaller plate pair and each tergum has a movable opercular valves including terga short spur at its base (Fig. 4), deep crests for and scuta (Newman 2007) (Figs. -

Hull Fouling Is a Risk Factor for Intercontinental Species Exchange in Aquatic Ecosystems

Aquatic Invasions (2007) Volume 2, Issue 2: 121-131 Open Access doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3391/ai.2007.2.2.7 © 2007 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2007 REABIC Research Article Hull fouling is a risk factor for intercontinental species exchange in aquatic ecosystems John M. Drake1,2* and David M. Lodge1,2 1Department of Biological Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556 USA 2Environmental National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis, 735 State Street, Suite 300, Santa Barbara, CA 93101 USA *Corresponding author Current address: Institute of Ecology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602 USA E-mail: [email protected] (JMD) Received: 13 March 2007 / Accepted: 25 May 2007 Abstract Anthropogenic biological invasions are a leading threat to aquatic biodiversity in marine, estuarine, and freshwater ecosystems worldwide. Ballast water discharged from transoceanic ships is commonly believed to be the dominant pathway for species introduction and is therefore increasingly subject to domestic and international regulation. However, compared to species introductions from ballast, translocation by biofouling of ships’ exposed surfaces has been poorly quantified. We report translocation of species by a transoceanic bulk carrier intercepted in the North American Great Lakes in fall 2001. We collected 944 individuals of at least 74 distinct freshwater and marine taxa. Eight of 29 taxa identified to species have never been observed in the Great Lakes. Employing five different statistical techniques, we estimated that the biofouling community of this ship comprised from 100 to 200 species. These findings adjust upward by an order of magnitude the number of species collected from a single ship. -

The Barnacle Amphibalanus Improvisus (Darwin, 1854), and the Mitten Crab Eriocheir: One Invasive Species Getting Off on Another!

BioInvasions Records (2015) Volume 4, Issue 3: 205–209 Open Access doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3391/bir.2015.4.3.09 © 2015 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2015 REABIC Rapid Communication The barnacle Amphibalanus improvisus (Darwin, 1854), and the mitten crab Eriocheir: one invasive species getting off on another! Murtada D. Naser1,4, Philip S. Rainbow2, Paul F. Clark2*, Amaal Gh. Yasser1,4 and Diana S. Jones3 1Marine Biology Department, Marine Science Centre, University of Basrah, Basrah, Iraq 2Department of Life Sciences, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, England 3Western Australian Museum, 49 Kew Street, Welshpool, Western Australia, 6106 Australia 4Australian Rivers Institute, Griffith University, 170 Kessels Road, Nathan, Queensland, 4111 Australia E-mail: [email protected] (MDN), [email protected] (PSR), [email protected] (PFC), [email protected] (AGY), [email protected] (DSJ) *Corresponding author Received: 9 March 2015 / Accepted: 20 May 2015 / Published online: 16 June 2015 Handling editor: Vadim Panov Abstract The balanoid barnacle, Amphibalanus improvisus (Darwin, 1854), was found on the carapaces of two invasive species of mitten crabs: Eriocheir sinensis H. Milne Edwards, 1853 and E. hepuensis Dai, 1991. The first instance was from a female mitten crab captured from the River Thames estuary, Kent, England, where A. improvisus is common. However, the second record, on a Hepu mitten crab from Iraq is the first record of A. improvisus from the Persian Gulf. Key words: Eriocheir sinensis H. Milne Edwards, 1853, E. hepuensis Dai, 1991, invasive species, England, Iraq, barnacles, mitten crabs Introduction the eastern and western North Atlantic; Baltic Sea; west coast of Africa (to the Cape of Good “Hairy” (Southeast and East Asia) or “mitten” Hope); Mediterranean Sea; Black Sea; Caspian (Europe) crabs are currently assigned to Eriocheir Sea; Red Sea; Straits of Malacca; Singapore; De Haan, 1835 (Brachyura: Grapsoidea: Varunidae). -

A Checklist of Turtle and Whale Barnacles

Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2013, 93(1), 143–182. # Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2012 doi:10.1017/S0025315412000847 A checklist of turtle and whale barnacles (Cirripedia: Thoracica: Coronuloidea) ryota hayashi1,2 1International Coastal Research Center, Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, The University of Tokyo, 5-1-5, Kashiwanoha, Kashiwa-shi, Chiba 277-8564 Japan, 2Marine Biology and Ecology Research Program, Extremobiosphere Research Center, Japan Agency for Marine–Earth Science and Technology A checklist of published records of coronuloid barnacles (Cirripedia: Thoracica: Coronuloidea) attached to marine vertebrates is presented, with 44 species (including 15 fossil species) belonging to 14 genera (including 3 fossil genera) and 3 families recorded. Also included is information on their geographical distribution and the hosts with which they occur. Keywords: checklist, turtle barnacles, whale barnacles, Chelonibiidae, Emersoniidae, Coronulidae, Platylepadidae, host and distribution Submitted 10 May 2012; accepted 16 May 2012; first published online 10 August 2012 INTRODUCTION Superorder THORACICA Darwin, 1854 Order SESSILIA Lamarck, 1818 In this paper, a checklist of barnacles of the superfamily Suborder BALANOMORPHA Pilsbry, 1916 Coronuloidea occurring on marine animals is presented. Superfamily CORONULOIDEA Newman & Ross, 1976 The systematic arrangement used herein follows Newman Family CHELONIBIIDAE Pilsbry, 1916 (1996) rather than Ross & Frick (2011) for reasons taken up in Hayashi (2012) in some detail. The present author Genus Chelonibia Leach, 1817 deems the subfamilies of the Cheonibiidae (Chelonibiinae, Chelonibia caretta (Spengler, 1790) Emersoniinae and Protochelonibiinae) proposed by Harzhauser et al. (2011), as well as those included of Ross & Lepas caretta Spengler, 1790: 185, plate 6, figure 5. -

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES an Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES An Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals By Paul Rudy, Jr. Lynn Hay Rudy Oregon Institute of Marine Biology University of Oregon Charleston, Oregon 97420 Contract No. 79-111 Project Officer Jay F. Watson U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 500 N.E. Multnomah Street Portland, Oregon 97232 Performed for National Coastal Ecosystems Team Office of Biological Services Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 Table of Contents Introduction CNIDARIA Hydrozoa Aequorea aequorea ................................................................ 6 Obelia longissima .................................................................. 8 Polyorchis penicillatus 10 Tubularia crocea ................................................................. 12 Anthozoa Anthopleura artemisia ................................. 14 Anthopleura elegantissima .................................................. 16 Haliplanella luciae .................................................................. 18 Nematostella vectensis ......................................................... 20 Metridium senile .................................................................... 22 NEMERTEA Amphiporus imparispinosus ................................................ 24 Carinoma mutabilis ................................................................ 26 Cerebratulus californiensis .................................................. 28 Lineus ruber ......................................................................... -

Acidophilic Green Algal Genome Provides Insights Into Adaptation to an Acidic Environment

Acidophilic green algal genome provides insights into adaptation to an acidic environment Shunsuke Hirookaa,b,1, Yuu Hirosec, Yu Kanesakib,d, Sumio Higuchie, Takayuki Fujiwaraa,b,f, Ryo Onumaa, Atsuko Eraa,b, Ryudo Ohbayashia, Akihiro Uzukaa,f, Hisayoshi Nozakig, Hirofumi Yoshikawab,h, and Shin-ya Miyagishimaa,b,f,1 aDepartment of Cell Genetics, National Institute of Genetics, Shizuoka 411-8540, Japan; bCore Research for Evolutional Science and Technology, Japan Science and Technology Agency, Saitama 332-0012, Japan; cDepartment of Environmental and Life Sciences, Toyohashi University of Technology, Aichi 441-8580, Japan; dNODAI Genome Research Center, Tokyo University of Agriculture, Tokyo 156-8502, Japan; eResearch Group for Aquatic Plants Restoration in Lake Nojiri, Nojiriko Museum, Nagano 389-1303, Japan; fDepartment of Genetics, Graduate University for Advanced Studies, Shizuoka 411-8540, Japan; gDepartment of Biological Sciences, Graduate School of Science, University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan; and hDepartment of Bioscience, Tokyo University of Agriculture, Tokyo 156-8502, Japan Edited by Krishna K. Niyogi, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved August 16, 2017 (received for review April 28, 2017) Some microalgae are adapted to extremely acidic environments in pumps that biotransform arsenic and archaeal ATPases, which which toxic metals are present at high levels. However, little is known probably contribute to the algal heat tolerance (8). In addition, the about how acidophilic algae evolved from their respective neutrophilic reduction in the number of genes encoding voltage-gated ion ancestors by adapting to particular acidic environments. To gain channels and the expansion of chloride channel and chloride car- insights into this issue, we determined the draft genome sequence rier/channel families in the genome has probably contributed to the of the acidophilic green alga Chlamydomonas eustigma and per- algal acid tolerance (8). -

King's Research Portal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by King's Research Portal King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1016/j.shpsc.2017.07.002 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Manias, C. (2017). Progress in Life’s History: Linking Darwinism and Palaeontology in Britain, 1860-1914. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2017.07.002 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

A New Species of Lepas (Crustacea: Cirripedia: Pedunculata) from the Miocene Mizunami Group, Japan

Bulletin of the Mizunami Fossil Museum, no. 31 (2004), p. 91-93, 1 fig. c 2004, Mizunami Fossil Museum A new species of Lepas (Crustacea: Cirripedia: Pedunculata) from the Miocene Mizunami Group, Japan Hiroaki Karasawa*, Toshio Tanaka* *, and Yoshitsugu Okumura*** * Mizunami Fossil Museum, Yamanouchi, Akeyo, Mizunami, Gifu 509-6132, Japan <[email protected]> ** Aichi Gakuin Junior College, Chikusa, Nagoya 464-8650, Japan < [email protected]> *** Mizunami Fossil Museum, Yamanouchi, Akeyo, Mizunami, Gifu 509-6132, Japan <[email protected]> Abstract Lepas kuwayamai, a new species of a lepadid thracican is described from the lower Miocene Mizunami Group in Gifu Prefecture, Honshu, Japan. This represents the third record for the family from Miocene deposits of Japan. Key words: Crustacea, Cirripedia, Thoracica, Pedunculata, Lepadidae, Lepas, Miocene, Japan Material examined: MFM9043, holotype; 8 paratypes, Introduction MFM9044-9051; Coll. M. Kuwayama in, 2004. All specimens are housed in the Mizunami Fossil Museum. The lepadomorph family Lepadidae Darwin, 1851, is a Diagnosis: Lepas with moderate sized capitulum. Shell small group including six genera (Newman, 1996). Among thick. Scutum triangular, slightly higher than wide, with these, the genus Lepas Linnaeus, 1758, is only known clear growth lines; umbonal tooth absent; very weak from Japan in the fossil record. O’hara et al. (1976) reported radial striae sometimes present; apicoumbonal ridge Lepas sp. from the middle Pleistocene Shimosa Group and weak. Tergum flattened without radial striae; occludent unnamed Miocene species was reported from the lower margin convex, rounded. Carina broad. Miocene Morozaki Group (Mizuno and Takeda, 1993) and Etymology: In honor to our friend, Mr.