Future of Newspapers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

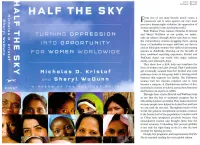

2016 Austin College Posey Leadership Award Co-Recipients: Sheryl Wudunn & Nicholas Kristof

2016 Austin College Posey Leadership Award Co-Recipients: Sheryl WuDunn & Nicholas Kristof Founders of the Half the Sky Movement Sheryl WuDunn grew up in New York City, a third-generation Chinese American hailing from the Upper West Side. She earned an MBA from Harvard Business School and a master’s degree in public administration from Princeton University. WuDunn has worked in investment management at Goldman, Sachs & Co. and was a commercial loan officer at Bankers Trust. In addition, she spent time at The New York Times as both a journalist and an executive. During her time as a journalist, WuDunn and her husband, Nicholas Kristof, won a Pulitzer Prize for their coverage of China’s Tiananmen Square movement in 1990. Nicholas Kristof grew up on a sheep and cherry farm near Yamhill, Oregon. He graduated from Harvard College and won a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford, where he studied law. He later studied Arabic in Cairo and Chinese in Taipei. Kristof’s work has taken him all over the world. He has lived on four continents, reported on six, and traveled to more than 150 countries, plus all 50 U.S. states, every Chinese province, and every main Japanese island. Joining The New York Times in 1984, Kristof initially covered economics. Since 2001, he has maintained an op-ed column. In addition to his 1990 Pulitzer honors for coverage of China’s Tiananmen Square movement, Kristof won a second Pulitzer Prize in 2006 for his journalistic coverage of the genocides in Darfur. The latest book by WuDunn and Kristof is A Path Appears: Transforming Lives, Creating Opportunity (2014). -

Willing & Able

MORE WILLING & ABLE: Charting China’s International Security Activism By Ely Ratner, Elbridge Colby, Andrew Erickson, Zachary Hosford, and Alexander Sullivan Foreword Many friends have contributed immeasurably to our research over the past two years and to this culminating report. CNAS colleagues including Patrick Cronin, Shawn Brimley, Jeff Chism, Michèle Flournoy, Richard Fontaine, Jerry Hendrix, Van Jackson, JC Mock, Dafna Rand, Jacob Stokes, and Robert Work provided feedback and guidance through- out the process. We are also grateful to our expert external reviewers: Scott Harold, Evan Montgomery, John Schaus, and Christopher Yung. David Finkelstein and Bonnie Glaser lent their wisdom to workshops that greatly informed our subsequent efforts. The research team is indebted to the School of International Studies at Peking University, the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Global Policy, China Institute for Contemporary International Relations, and China Foreign Affairs University for hosting discussions in Beijing. We were guided and assisted throughout by colleagues from the State Department, the Department of Defense, the White House, and the U.S. intelligence community. Kelley Sayler, Yanliang Li, Andrew Kwon, Nicole Yeo, Cecilia Zhou, and Hannah Suh provided key research, editing, and other support. The creativity of Melody Cook elevated the report and its original graphics. We are grateful as well for the assistance of Ellen McHugh and Ryan Nuanes. Last but not least, this research would not have been possible without the generous support -

Joint Force Quarterly 97

Issue 97, 2nd Quarter 2020 JOINT FORCE QUARTERLY Broadening Traditional Domains Commercial Satellites and National Security Ulysses S. Grant and the U.S. Navy ISSUE NINETY-SEVEN, 2 ISSUE NINETY-SEVEN, ND QUARTER 2020 Joint Force Quarterly Founded in 1993 • Vol. 97, 2nd Quarter 2020 https://ndupress.ndu.edu GEN Mark A. Milley, USA, Publisher VADM Frederick J. Roegge, USN, President, NDU Editor in Chief Col William T. Eliason, USAF (Ret.), Ph.D. Executive Editor Jeffrey D. Smotherman, Ph.D. Production Editor John J. Church, D.M.A. Internet Publications Editor Joanna E. Seich Copyeditor Andrea L. Connell Associate Editor Jack Godwin, Ph.D. Book Review Editor Brett Swaney Art Director Marco Marchegiani, U.S. Government Publishing Office Advisory Committee Ambassador Erica Barks-Ruggles/College of International Security Affairs; RDML Shoshana S. Chatfield, USN/U.S. Naval War College; Col Thomas J. Gordon, USMC/Marine Corps Command and Staff College; MG Lewis G. Irwin, USAR/Joint Forces Staff College; MG John S. Kem, USA/U.S. Army War College; Cassandra C. Lewis, Ph.D./College of Information and Cyberspace; LTG Michael D. Lundy, USA/U.S. Army Command and General Staff College; LtGen Daniel J. O’Donohue, USMC/The Joint Staff; Brig Gen Evan L. Pettus, USAF/Air Command and Staff College; RDML Cedric E. Pringle, USN/National War College; Brig Gen Kyle W. Robinson, USAF/Dwight D. Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy; Brig Gen Jeremy T. Sloane, USAF/Air War College; Col Blair J. Sokol, USMC/Marine Corps War College; Lt Gen Glen D. VanHerck, USAF/The Joint Staff Editorial Board Richard K. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Deborah L. Rhode* This Article Explores the Leadership Challenges That Arose in the Wake of the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic and the W

9 RHODE (DO NOT DELETE) 5/26/2021 9:12 AM LEADERSHIP IN TIMES OF SOCIAL UPHEAVAL: LESSONS FOR LAWYERS Deborah L. Rhode* This article explores the leadership challenges that arose in the wake of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic and the widespread protests following the killing of an unarmed Black man, George Floyd. Lawyers have been key players in both crises, as politicians, general counsel, and leaders of protest movements, law firms, bar associations, and law enforcement agencies. Their successes and failures hold broader lessons for the profession generally. Even before the tumultuous spring of 2020, two-thirds of the public thought that the nation had a leadership crisis. The performance of leaders in the pandemic and the unrest following Floyd’s death suggests why. The article proceeds in three parts. Part I explores leadership challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic and the missteps that put millions of lives and livelihoods as risk. It begins by noting the increasing frequency and intensity of disasters, and the way that leadership failures in one arena—health, environmental, political, or socioeconomic—can have cascading effects in others. Discussion then summarizes key leadership attributes in preventing, addressing, and drawing policy lessons from major crises. Particular attention centers on the changes in legal workplaces that the lockdown spurred, and which ones should be retained going forward. Analysis also centers on gendered differences in the way that leaders addressed the pandemic and what those differences suggest about effective leadership generally. Part II examines leadership challenges in the wake of Floyd’s death for lawyers in social movements, political positions, private organizations, and bar associations. -

Anonymous Sources: More Or Less and Why and Where?

Southwestern Mass Communication Journal A journal of the Southwest Education Council for Journalism & Mass Communication ISSN 0891-9186 | Vol. 30, No. 2 | Spring 2015 Anonymous Sources: More or less and why and where? Hoyt Purvis University of Arkansas Anonymous sources have been important factors in some of the major news stories of our time. But does this reliance on unnamed sources to too far? The use and possible abuse of anonymous sources is a matter of continuing controversy in the media and can have a direct bearing on the credibility of the media. Questions related to the use of such sources are examined in a study of the use of anonymous sources in 14 daily editions of three daily newspapers, focusing on the quantity of articles using anonymous sources, their subject matter, location, and rationale for using unnamed sources. This is done within the context of the ongoing controversy about the reliance on such sources in major news organizations. Results of this study are reported and analyzed and provide some clear indications about the extent and nature of the use of anonymous sources, and point to a possible over-dependence and problematic trend. Suggested citation: Purvis, H. (2015). Anonymous sources: More or less and why and where?. Southwestern Mass Communication Journal, 30(2). Retrieved from http://swecjmc.wp.txstate.edu. The Southwestern Mass Communication Journal Spring 2015 V. 30, No. 2 The Southwestern Mass Communication Journal (ISSN 0891-9186) is published semi-annually by the Southwest Education Council for Journalism and Mass Communication. http://swmcjournal.com Also In This Issue: Anonymous Sources: More or less and why and where? Hoyt Purvis, University of Arkansas Are You Talking To Me? The Social-Political Visual Rhetoric of the Syrian Presidency’s Instagram Account Steven Holiday & Matthew J. -

By Any Other Name: How, When, and Why the US Government Has Made

By Any Other Name How, When, and Why the US Government Has Made Genocide Determinations By Todd F. Buchwald Adam Keith CONTENTS List of Acronyms ................................................................................. ix Introduction ........................................................................................... 1 Section 1 - Overview of US Practice and Process in Determining Whether Genocide Has Occurred ....................................................... 3 When Have Such Decisions Been Made? .................................. 3 The Nature of the Process ........................................................... 3 Cold War and Historical Cases .................................................... 5 Bosnia, Rwanda, and the 1990s ................................................... 7 Darfur and Thereafter .................................................................... 8 Section 2 - What Does the Word “Genocide” Actually Mean? ....... 10 Public Perceptions of the Word “Genocide” ........................... 10 A Legal Definition of the Word “Genocide” ............................. 10 Complications Presented by the Definition ...............................11 How Clear Must the Evidence Be in Order to Conclude that Genocide has Occurred? ................................................... 14 Section 3 - The Power and Importance of the Word “Genocide” .. 15 Genocide’s Unique Status .......................................................... 15 A Different Perspective .............................................................. -

College Voice Vol. 97 No. 12

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College 2013-2014 Student Newspapers 4-1-2014 College Voice Vol. 97 No. 12 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2013_2014 Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "College Voice Vol. 97 No. 12" (2014). 2013-2014. 3. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2013_2014/3 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2013-2014 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. ••• • I' •.• • ~ • ~~-rHE LLEGEv I-E :~~F~~-.-- CONNECTICUT COllEGE'S INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER CLASS PRESIDENT #lrnpeachPrashanth Movement Gains Momentum DAVE SHA"4FIELD EDITOR IN CHIEF A poll taken earlier this semester re- unaware of his prestigious title until they vealed that the overwhelming majority received an invitation for the 100 Days of the graduating class could not identify [until Graduation] Party this February, their class president. Of the nearly 300 signed by their president. students surveyed, 82% could not name Like many other seniors, 2014 Social the 2014 class president, 11% were un- Chair Peter Herron was caught unaware aware that Class Council existed in any by Selvam's presumptuous signoff', capacity and only 7% correctly identified even after having worked alongside him their elected leader. However, 100% of on Class Council. Said Herron, "I like the graduating class agreed that whoever Prashanth a lot, but I always thought we the president might be, her or she is do- were, you know.just hanging out, not do- ing a terrible job, ing 'class business' or whatever. -

From Two of Our Most Fiercely Moral Voices, A

U.S.A. :)>27·95 CANADA $34.00 rom two of our most fiercely moral voices, a Fpassionate call to arms against our era's most pervasive human rights violation: the oppression of women and girls in the developing world. With Pulitzer Prize winners Nicholas D. Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn as our guides, we under take an odyssey through Africa and Asia to meet the extraordinary women struggling there, among them a Cambodian teenager sold into sex slavery and an Ethiopian woman who suffered devastating injuries in childbirth. Drawing on the breadth of their combined reporting experience, Kristof and WuDunn depict our world with anger, sadness, clarity, and, ultimately, hope. They show how a little help can transform the lives of women and girls abroad. That Cambodian girl eventually escaped from her brothel and, with assistance from an aid group, built a thriving retail business that supports her family. The Ethiopian woman had her injuries repaired and in time became a surgeon. A Zimbabwean mother of five, counseled to return to school, earned her doctorate and became an expert on AIDS. Through these stories, Kristof and WuDunn help us see that the key to economic progress lies in unleashing women's potential. They make clear how so many people have helped to do just that, and how we can each do our part. Throughout much of the world, the greatest unexploited economic resource is the fema le half of the population. Countries such as China have prospered precisely hecause they emancipated women and brought them into the form al economy. -

May 12, 2006 Exhibits a Through F

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 1 ) CR. NO 05-394 (RBW) v. ) ) I. LEWIS LIBBY, ) also known as "Scooter Libby" ) EXHIBITS A THROUGH F Respectfully submitted, PATRICK J. FIT~ERALD Special Counsel Office of the United States Attorney Northern District of Illinois 2 19 South Dearborn Street Chicago, Illinois 60604 (312) 353-5300 Dated: May 12,2006 Page 2 The New York Times May 6,2003 Tuesday 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company The New York Times May 6,2003 Tuesday Late Edition - Final SECTION: Section A; Column 1; Editorial Desk; Pg. 31 LENGTH: 726 words HEADLINE: Missing In Action: Truth BYLINE: By NICHOLAS D. KRISTOF; E-mail: [email protected] BODY: When I raised the Mystery of the Missing W.M.D. recently, hawks fired barrages of reproachful e-mail at me. The gist was: "You *&#*! Who cares if we never find weapons of mass destruction, because we've liberated the Iraqi people frOm a murderous tyrant." But it does matter, enormously, for American credibility. After all, as Ari Fleischer said on April 10 about W.M.D.: "That is what this war was about." I rejoice in the newfound freedoms in Iraq. But there are indications that the U.S.government souped up intelligence, leaned on spooks to change their conclusions and concealed contrary information to deceive people at home and around the world. Let's fervently hope that tomorrow we find an Iraqi superdome filled with 500 tons of mustard gas and nerve gas, 25,000 liters of anthrax, 38,000 liters of botulinum toxin, 29,984 prohibited munitions capable of delivering chemical agents, several dozen Scud missiles, gas centrifuges to enrich uranium, 18mobile biological warfare factories, long- range unmanned aerial vehicles to dispense anthrax, and proof of close ties with Ai Qaeda. -

OPC Forges Partnership to Promote Journalists' Safety Club Mixers To

THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB OF AMERICA, NEW YORK, NY • November 2014 OPC Forges Partnership to Promote Journalists’ Safety By Marcus Mabry compact between Your OPC has been busy! Since news organiza- the new officers and board of gov- tions and journal- ernors took office at the end of ists, in particular the summer, we have dedicated freelance, around ourselves to three priorities, all safety and profes- designed to increase the already sionalism. We have impressive contribution that the only just begun, but OPC makes to our members and our partners include our industry. the Committee to We have restructured the board Protect Journalists, to dedicate ourselves to services Reporters Without for members, both existing and po- Borders, the Front- tential, whether those members are line Club, the In- Clockwise from front left: Vaughan Smith, Millicent veteran reporters and editors, free- ternational Press Teasdale, Patricia Kranz, Jika Gonzalez, Michael Luongo, Institute’s Foreign Sawyer Alberi, Judi Alberi, Micah Garen, Marcus Mabry, lancers or students. In addition to Charles Sennott, Emma Daly and Judith Matloff dining services, we have reinvigorated our Editors Circle and after a panel of how to freelance safety. See page 3. social mission, creating a committee the OPC Founda- dedicated to planning regular net- tion. We met in September at The you need and the social events you working opportunities for all mem- New York Times headquarters to want. And, just as important, get bers. So if you are in New York – or try to align efforts that many of our friends and colleagues who are not coming through New York – look us groups had started separately. -

Floyd Abrams

Potential Witnesses and Names that may be Mentioned during the Trial • Floyd Abrams (Partner at the law firm • Donald Fierce (Government Relations Cahill, Gordon & Reindell) Consultant) • Spencer Ackerman (Journalist) • Alan Foley (CIA Official) • David Addington (Vice President • Carl Ford (State Department Official) Cheney’s Chief of Staff) • Gerard Francisco (Office of Special • Mike Allen (Washington Post Counsel) Reporter) • Paul Gigot (Journalist for the Wall • Michael Anton (National Security Street Journal) Council Official) • David Gregory (Chief White House • Kirk Armfield (FBI Agent) Correspondent for NBC News) • Richard Armitage (Former Deputy • Robert Grenier (Former CIA Official) Secretary of State) • Marc Grossman (Former • Daniel Bartlett (Counselor to the Undersecretary of State) President) • Stephen Hadley (President Bush’s • Robert Bennett (Partner at the law National Security Advisor) firm Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & • John Hannah (Vice President Flom) Cheney’s National Security Advisor) • Deborah Bond (FBI Agent) • Bill Harlow (CIA Official) • Massimo Calabresi (Time Magazine • Debra Heiden (Assistant to the Vice Reporter) President) • Andrew Card (President Bush’s • Seymour Hersh (Journalist, former Chief of Staff) Contributor to The New Yorker) • Jay Carney (Time Magazine Editor) • Richard Hohlt (Consultant) • Vice President Richard B. Cheney • Bob Joseph (Under Secretary of State) • Matthew Cooper (Time Magazine • John Judis (Editor, The New Reporter) Republic) • John Dickerson (Journalist) • Glenn Kessler