Urban Journal May 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Sundance Film Festival: Amid Record High Submissions, Announcing New Hires, Talent Forum, Data-Driven Demographic Initiatives & Critic Stipends

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: November 19, 2018 Spencer Alcorn 310.360.1981 [email protected] 2019 Sundance Film Festival: Amid Record High Submissions, Announcing New Hires, Talent Forum, Data-Driven Demographic Initiatives & Critic Stipends Park City, Utah — With less than two weeks until the program is announced, and less than three months until Day One, Sundance Institute today announces new hires on its programming team and new initiatives to deepen support for independent storytellers and broaden access to the Festival. The 2019 Festival will showcase work drawn from over 14,200 submissions, a record high. Kim Yutani, the Festival’s recently-named Director of Programming, said: “This year’s record-breaking number of submissions are phenomenally strong: we’re invigorated and inspired by the work we’ve been seeing. Our incredible -- and growing! -- programming team has refined our curation processes, ensuring that the conversations we have as we program continue to center, as always, on a Festival that represents a wide range of filmmakers and on-screen experiences. We’re also continually evolving our process to incorporate data and research findings.” Program Team Evolves: The new hires mentioned by Yutani include expanding and refining the Programming and screener teams, with an eye towards fresh perspectives and varied decision-making voices. Dilcia Barrera joins as Programmer; Stephanie Owens as Associate Programmer; Sudeep Sharma as Shorts Programmer and Ana Souza (formerly a Programming Coordinator) is promoted to Manager, Programming / Associate Programmer. Including these new additions, women comprise half of the Sundance Film Festival programming team.Tabitha Jackson, Director of the Institute’s Documentary Film Program, will program a strand of panels under programmer John Nein. -

Precarity and Belonging in the Work of Teju Cole

Luke Watson MA Dissertation 2019 Black Bodies in the Open City: Precarity and Belonging in the work of Teju Cole Luke Watson (WTSLUK001) A minor dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in English Language, Literature & Modernity Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town 2019 COMPULSORY DECLARATION This work hasUniversity not been previously submitted of inCape whole, or in part, Town for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature: Date: 4 June 2019 1 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Luke Watson MA Dissertation 2019 Abstract This dissertation attempts to read Nigerian-American writer Teju Cole’s fiction and essays as sustained demonstrations of precarity, as theorised by Judith Butler in Precarious Life (2004). Though never directly cited by Cole, Butler’s articulation of a shared condition of bodily vulnerability and interdependency offers a generative critical framework through which to read Cole’s representations of black bodies as they move across space. By presenting the ‘black body’, rather than ‘black man’, as the preferred metonym for black people, Cole’s work, which I argue can be read as peculiar travel narratives, foregrounds the bodily dimension of black life, and develops an ambivalent storytelling mode to narrate the experiences of characters who encompass multiple spatialities and subjectivities. -

Emhs 9Th Summer Reading 1

Annotation Directions: EMHS 9TH SUMMER READING 1. Make a point of underlining the two most important ideas in each “column” of reading. Each year, students at EMHS do summer reading. You can underline a single phrase or a couple Reading over the summer keeps one’s mind “awake” of sentences, but please choose your selections and provides your class with an immediate platform carefully. to work on from the first day of school. The material for this packet was selected for its subject matter and 2. Of the two ideas you underline in each column, relevance to you. select the most important one and rephrase it at the bottom of the page in your own words. Please make a point of reading all six of the articles 3. When you finish an article, review your contained in this packet. Since there are several annotations. On a separate sheet of paper, different pieces, you can break this reading up as write down the “takeaway points” for each your summer schedule allows. All articles should article—the most important ideas. be read and annotated by the first day of school. Please bring this packet with you on There are many online sources to further explain the first day of school. how to annotate a text. When you come to school on the first day, this packet should be completely read This packet should be printed out and read carefully. and annotated. In addition, you should have You should always read with a pen or pencil and use your takeaway points on a separate sheet of annotation strategies to help yourself make sense paper completed. -

The Rise of Twitter Fiction…………………………………………………………1

Twitter Fiction: A Shift in Author Function Hilary Hyman Twitter fiction, an example of twenty-first century digital narrative, allows authors to experiment with literary form, production, and dissemination as they engage readers through a communal network. Twitter offers creative space for both professionals and amateurs to publish fiction digitally, enabling greater collaboration among authors and readers. Examining Jennifer Egan’s “Black Box” and selected Twitter stories from Junot Diaz, Teju Cole, and Elliott Holt, this thesis establishes two distinct types of Twitter fiction—one produced for the medium and one produced through it—to consider how Twitter’s present feed and character limit fosters a uniquely interactive reading experience. As the conversational medium calls for present engagement with the text and with the author, Twitter promotes newly elastic relationships between author and reader that renegotiate the former boundaries between professionals and amateurs. This thesis thus considers how works of Twitter fiction transform the traditional author function and pose new questions regarding digital narrative’s modes of existence, circulation, and appropriation. As digital narrative makes its way onto democratic forums, a shifted author function leaves us wondering what it means to be an author in the digital age. Twitter Fiction: A Shift in Author Function Hilary Anne Hyman Twitter Fiction: A Shift in Author Function Hilary Anne Hyman An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of English at Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major April 18, 2016 Thesis Adviser: Vera Kutzinski Date Second Reader: Haerin Shin Date Program Director: Teresa Goddu Date For My Parents Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge Professor Teresa Goddu for shaping me into the writer I have become. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Staging Mysteries

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Staging Mysteries: Transnational Medievalist Performance in the Twentieth Century A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies by Carla Neuss 2021 ã Copyright by Carla Neuss 2021 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Staging Mysteries: Transnational Medievalist Performance in the Twentieth Century by Carla Neuss Doctor of Philosophy in Theatre and Performance Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2021 Professor Sean Metzger, Chair This dissertation traces adapted forms of the medieval mystery cycle tradition within different transnational moments of social, political, and cultural crisis. In redirecting the spiritually didactic aims of medieval performance, the modern mysteries that constitute this project illuminate how medieval theatre functions as an historical imaginary for the transformative potential of performance. This project investigates three twentieth-century adaptations of the medieval mystery cycle tradition: Alexander Scriabin’s unfinished multi-genre performance, Mysterium (c. 1910); Jean Paul Sartre’s first play, Bariona (1940); and a South African production of the Chester Mystery Cycle, Yiimimangaliso (2000). Chapter 2 demonstrates how Mysterium sought to enact a distinctly medieval imaginary of spiritual unity epitomized by the Russian religious value of sobornost.’ In analyzing its Russian Symbolist aesthetics, I argue that the Mysterium was designed phenomenologically to enact social transformation on the eve of the Soviet revolution ii through "affective atmosphere.” Chapter 3 discusses Jean-Paul Sartre's relatively unknown play Bariona as an adaptation of the medieval French nativity play tradition produced during World War II. This chapter situates Bariona within the longstanding tradition of French medievalist performance as a contested political site within the national consciousness. -

The Great Unwashed Public Baths in Urban America, 1840-1920

Washiîi! The Great Unwashed Public Baths in Urban America, 1840-1920 a\TH5 FOR Marilyn Thornton Williams Washing "The Great Unwashed" examines the almost forgotten public bath movement of the nineteenth and early twentieth cen turies—its origins, its leaders and their motives, and its achievements. Marilyn Williams surveys the development of the American obsession with cleanliness in the nineteenth century and discusses the pub lic bath movement in the context of urban reform in New York, Baltimore, Philadel phia, Chicago, and Boston. During the nineteenth century, personal cleanliness had become a necessity, not only for social acceptability and public health, but as a symbol of middle-class sta tus, good character, and membership in the civic community. American reformers believed that public baths were an impor tant amenity that progressive cities should provide for their poorer citizens. The bur geoning of urban slums of Irish immi grants, the water cure craze and other health reforms that associated cleanliness with health, the threat of epidemics—es pecially cholera—all contributed to the growing demand for public baths. New waves of southern and eastern European immigrants, who reformers perceived as unclean and therefore unhealthy, and in creasing acceptance of the germ theory of disease in the 1880s added new impetus to the movement. During the Progressive Era, these fac tors coalesced and the public bath move ment achieved its peak of success. Between 1890 and 1915 more than forty cities constructed systems of public baths. City WASHING "THE GREAT UNWASHED" URBAN LIFE AND URBAN LANDSCAPE SERIES Zane L. Miller and Henry D. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Post-American Novel: 9/11, the Iraq War, and the Crisis of American Hegemony Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1cs8p0b4 Author Page, Gabriel Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Post-American Novel: 9/11, the Iraq War, and the Crisis of American Hegemony By Gabriel Page A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Donna V. Jones, Chair Professor Karl Britto Professor Francine Masiello Professor Nadia Ellis Fall 2018 Abstract The Post-American Novel: 9/11, the Iraq War, and the Crisis of American Hegemony by Gabriel Page Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Donna V. Jones, Chair This dissertation proposes a new analytical category for thinking about a subset of post-9/11 Anglophone novels that are engaged with the political aftermath of 9/11. I designate this category the post-American novel, distinguishing it from the category of 9/11 fiction. While the 9/11 novel is a sub-genre of national literature, focusing on the terrorist attacks as a national trauma, the post-American novel is a transnational literary form that decenters 9/11, either by contextualizing the terrorist attacks in relation to other historical traumas or by shifting focus to the “War on Terror.” I theorize the post-American novel as the literary expression of international opposition to the 2003 U.S. -

The Language Spoken by All

Discussing Teju Cole’s essays on photography, Lu asks: How should we approach a medium that readily lends itself to distortion? In response, she develops an argument that urges us to reassess our identities in light of the global community with which photography can bring us into contact. (Instructor: Christina van Houten) THE LANGUAGE SPOKEN BY ALL Alice Lu he camera is—and always will be—a tool, an instrument, a weapon. Whether it has a detrimental or beneficial impact is the decision the photographer must make. However, whether we let a photograph’s message influence us or not Tis the decision we, the audience, must make. Teju Cole, a renowned writer and photographer, reckons with the positive and negative impacts of photography by relating the intricacies of the camera, the photographers, and the photographs themselves in a comprehensive ethical conversation. Cole takes his readers on a captivating journey through his collection of photo journals, using the camera as a lens to tackle cultural, technological, international, and personal issues. In doing so, he helps us rid ourselves of innocence and naivety and devel - op our own global perspectives. In such a diverse world, we need peo - ple with global perspectives, like Cole, to show us what we are doing wrong as brothers and sisters, as friends and strangers, and as human beings. In his essay “Against Neutrality,” Cole observes that in the eyes of many people, images “are often presumed to be unbiased.” They are snapshots of the real world, but we cannot assume that they are nec - essarily true. -

WHAT PHOTOGRAPHY TAUGHT ACCLAIMED AUTHOR TEJU COLE ABOUT WRITING by Rebecca Bengal, June 20, 2017

WHAT PHOTOGRAPHY TAUGHT ACCLAIMED AUTHOR TEJU COLE ABOUT WRITING By Rebecca Bengal, June 20, 2017 Ships circling the sea in Capri; the Alps seen between the flutter of laundry on a clothesline; a tipped-over cross in a field; the modern oddity of a person in an actual, working phone booth; sunlight streaming through the blinds, making slat-like shadows on the walls echoed by the stairs seen through a glass door. These photographs by Teju Cole—on view at Steven Kasher Gallery in New York—are framed more like windows than pictures. Adjacent to each black-bordered image, another framed space—like an opened shutter—accommodates an accompanying text. The words are intrinsic to the photographs, which are scenic, often in both a picturesque and theatrical sense. Taken in dozens of countries around the world, titled after the places of their origin—Fort Worth, Zürich, Brooklyn, Beirut, Lagos—they form a relentless moving picture, a roving novel, a travelogue, in the surreal spirit of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. “I am intrigued,” writes Cole in the afterword of his concurrently published fourth book Blind Spot, “by the continuity of places, by the singing line that connects them all.” Before he became known as a photographer, Teju Cole made his name as a novelist. For a writer, the “singing line” is narrative. In many ways, it’s no surprise that Cole was drawn to pick up a camera. “Photography seems to be the most literary of the graphic arts,” Walker Evans once wrote; a sentiment shared by the photographer William Gedney, who claimed to be “attempting a literary form in visual terms.” Cole’s widely acclaimed debut novel, Open City, is driven not by plot but by the act of walking and accidental physical encounters with place: The story stumbles upon itself. -

Leaves of Grass

Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman AN ELECTRONIC CLASSICS SERIES PUBLICATION Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman is a publication of The Electronic Classics Series. This Portable Document file is furnished free and without any charge of any kind. Any person using this document file, for any pur- pose, and in any way does so at his or her own risk. Neither the Pennsylvania State University nor Jim Manis, Editor, nor anyone associated with the Pennsylvania State University assumes any responsibility for the material contained within the document or for the file as an electronic transmission, in any way. Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman, The Electronic Clas- sics Series, Jim Manis, Editor, PSU-Hazleton, Hazleton, PA 18202 is a Portable Document File produced as part of an ongoing publication project to bring classical works of literature, in English, to free and easy access of those wishing to make use of them. Jim Manis is a faculty member of the English Depart- ment of The Pennsylvania State University. This page and any preceding page(s) are restricted by copyright. The text of the following pages are not copyrighted within the United States; however, the fonts used may be. Cover Design: Jim Manis; image: Walt Whitman, age 37, frontispiece to Leaves of Grass, Fulton St., Brooklyn, N.Y., steel engraving by Samuel Hollyer from a lost da- guerreotype by Gabriel Harrison. Copyright © 2007 - 2013 The Pennsylvania State University is an equal opportunity university. Walt Whitman Contents LEAVES OF GRASS ............................................................... 13 BOOK I. INSCRIPTIONS..................................................... 14 One’s-Self I Sing .......................................................................................... 14 As I Ponder’d in Silence............................................................................... -

Reading and Writing Socially During the Twitter Fiction Festival by Joachim Vlieghe, Kelly L

“Twitter, the most brilliant tough love editor youʼll ever have.” Readi…g socially during the Twitter Fiction Festival | Vlieghe | First Monday 27/10/16 0857 HOME ABOUT LOGIN REGISTER SEARCH CURRENT OPEN JOURNAL SYSTEMS ARCHIVES ANNOUNCEMENTS SUBMISSIONS Journal Help Home > Volume 21, Number 4 - 4 April 2016 > Vlieghe USER Username Password Remember me Login JOURNAL CONTENT Search All Search The communication practice of tweeting has fostered numerous literary Browse experiments, like Teju Cole’s series “Small fates” and Jennifer Egan’s novel By Issue “Black box”. In late 2012, these experiments culminated in an event that By Author focused on such literary experiments: the first Twitter Fiction Festival. In By Title this paper, we explore how people who participated in the festival use Other Journals tweeting to embrace and enact writing and reading literature as a social experience. The study includes a participant-centered inquiry based on two one-hour Twitter discussions with 14 participants from the Twitter Fiction FONT SIZE Festival as well as analyses of their online literary works and secondary sources related to the festival. We show that festival participants self- identify based on their creative and social practices as artists rather than with traditional labels such as writer or author and are therefore drawn to CURRENT ISSUE social media environments. Contents Introduction Theoretical framework: Art as a social system Method ARTICLE TOOLS Discussion Conclusion Abstract Limitations and future directions Print this article Indexing metadata How to cite Introduction item “As I began work on my new book, a non-fictional narrative of Lagos, and was paying more and more Supplementary attention to daily life in the city, a peculiar thing files happened. -

[email protected]

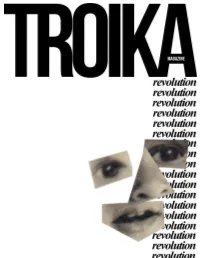

President, Kasia Metkowski Editor-in-Chief, John Dethlefsen Lead Designer, Leo Elyon Editor, Anashe Barton Editor, Ionela Maria Ciolan Editor, Caitlin Cozine Designer, Alexandra Dubinin Designer, Kylen Gensurowsky Editor, Alexandru Groza Administrative Assistant, Kevin Lasek Editor, Elizabeth Levinson Interested in submitting? Contact us at: [email protected] 1 now, Before We Begin a Letter from the President, This publication is ate career. Our grad- curacy of the content. made possible by sup- uate students partic- The opinions and Dear reader, port from the Institute ipate in the life of the views expressed in of Slavic, East Europe- Department (study- this publication are For this edition, we at Troika distinguished ourselves by picking a an, and Eurasian Stud- ing, teaching, run- those of the authors, theme that directly addresses the embittered temperament that, over ies at the University ning the library, and do not necessarily the past year, has crept into our lives. By “celebrating disillusion- of California, Berkeley, organizing film reflect the opinions ment,” we challenge this temperament. with funding from series, perfor- and views of the Troi- the US Department mances, colloquia, ka editors. Troika of Education Title conferences), in the does not endorse any This year, Berkeley students have grown especially weary, faced VI National Resource life of the Universi- opinions expressed by with constant protests and security measures surrounding both con- Centers Program. ty, and in the pro- the authors in this troversial speakers and unpopular election results, as well as the fession (reading pa- journal and shall not continual struggle against an unresponsive bureaucracy. Additionally, University of Cal- pers at national and be held liable for any millennials across the country have continued to experience decreas- ifornia, Berkeley, international- losses, claims, expens- ing job prospects, increasing debt, and a political system that is dis- Graduate Program conferences).