Understanding Tree-To-Tree Variations in Stone Pine (Pinus Pinea L.) Cone Production Using Terrestrial Laser Scanner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Lifestyle

UL introduces the Supplier Forum, a new and exciting way to learn about trends from industry experts. Urban Lifestyle Dr. Fred Zülli, Ph.D. Dr. Stefan Bänziger, Ph.D. Abbie Piero Managing Director Head of R&D and Engineering Forum Moderator Mibelle AG Biochemistry, Switzerland Lipoid Kosmetik UL Prospector Urban Lifestyle In 2030 more than 60% of total population will live in big cities Urbanization will change lifestyle New demand for cosmetics with increase in wellbeing © Mibelle Biochemistry, Switzerland 2020 Cosmetic Active Concepts 1. Hectic, stressed lifestyle → fighting skin irritations induced by glucocorticoids 2. Exhaustive lifestyle → boosting energy levels 3. Lack of sleep → avoiding skin aging by improved protein folding 4. Digital dependence → protection against blue light 5. Feel good → look good with phyto-endorphins 6. Health & eco-consciousness → supplementing skin care for a vegan lifestyle © Mibelle Biochemistry, Switzerland 2020 1. Hectic, Stressed Lifestyle and Skin © Mibelle Biochemistry, Switzerland 2020 What is Stress? Acute stress • Body's reaction to demanding or dangerous situations („fight or flight“) • Short term • Acute stress is thrilling and exciting and body usually recovers quickly • Adrenaline fight or flight © Mibelle Biochemistry, Switzerland 2020 What is Stress? Chronic stress • Based on stress factors that impact over a longer period • Always bad and has negative effects on the body and the skin • Glucocortioides (Cortisol) © Mibelle Biochemistry, Switzerland 2020 Sources of Psychological Stress -

Abacca Mosaic Virus

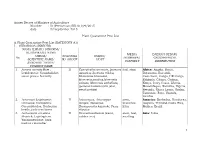

Annex Decree of Ministry of Agriculture Number : 51/Permentan/KR.010/9/2015 date : 23 September 2015 Plant Quarantine Pest List A. Plant Quarantine Pest List (KATEGORY A1) I. SERANGGA (INSECTS) NAMA ILMIAH/ SINONIM/ KLASIFIKASI/ NAMA MEDIA DAERAH SEBAR/ UMUM/ GOLONGA INANG/ No PEMBAWA/ GEOGRAPHICAL SCIENTIFIC NAME/ N/ GROUP HOST PATHWAY DISTRIBUTION SYNONIM/ TAXON/ COMMON NAME 1. Acraea acerata Hew.; II Convolvulus arvensis, Ipomoea leaf, stem Africa: Angola, Benin, Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae; aquatica, Ipomoea triloba, Botswana, Burundi, sweet potato butterfly Merremiae bracteata, Cameroon, Congo, DR Congo, Merremia pacifica,Merremia Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, peltata, Merremia umbellata, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Ipomoea batatas (ubi jalar, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, sweet potato) Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo. Uganda, Zambia 2. Ac rocinus longimanus II Artocarpus, Artocarpus stem, America: Barbados, Honduras, Linnaeus; Coleoptera: integra, Moraceae, branches, Guyana, Trinidad,Costa Rica, Cerambycidae; Herlequin Broussonetia kazinoki, Ficus litter Mexico, Brazil beetle, jack-tree borer elastica 3. Aetherastis circulata II Hevea brasiliensis (karet, stem, leaf, Asia: India Meyrick; Lepidoptera: rubber tree) seedling Yponomeutidae; bark feeding caterpillar 1 4. Agrilus mali Matsumura; II Malus domestica (apel, apple) buds, stem, Asia: China, Korea DPR (North Coleoptera: Buprestidae; seedling, Korea), Republic of Korea apple borer, apple rhizome (South Korea) buprestid Europe: Russia 5. Agrilus planipennis II Fraxinus americana, -

Eyre Peninsula Aleppo Pine Management Plan

Eyre Peninsula NRM Board PEST SPECIES REGIONAL MANAGEMENT PLAN Pinus halepensis Aleppo pine This plan has a five year life period and will be reviewed in 2023. It is most abundant on southern Eyre Peninsula, Yorke Peninsula INTRODUCTION and Mid-North, and less frequent in upper Eyre Peninsula and the Murray Mallee. Aleppo pines appear absent from the Synonyms pastoral zone. Pinus halepensis Mill., Gard. Dict., ed. 8. n.8. (1768) Infestations occur in Waitpinga Conservation Park, Innes Pinus abasica Carrière, Traité Gén. Conif. 352 (1855) National Park, Hindmarsh Island and many small parks in the Pinus arabica Sieber ex Spreng., Syst. Veg. 3: 886 (1826) Adelaide Hills. Large infestations of Aleppo pines occur on lower Pinus carica D.Don, Discov. Lycia 294 (1841) Eyre Peninsula along the Flinders Highway and many roadside Pinus genuensis J.Cook, Sketch. Spain 2:236 (1834) reserves, Uley Wanilla, Uley South and Lincoln Basin (SA Water Pinus hispanica J.Cook, Sketch. Spain 2:337 (1834) Corporation). Pinus loiseleuriana Carrière, Traité Gén. Conif. 382 (1855) Pinus maritima Mill., Gard. Dict. ed. 8. n.7. (1768) Pinus parolinii Vis., Mem. Reale Ist. Veneto Sci. 6: 243 (1856) Pinus penicillus Lapeyr., Hist. Pl. Pyrénées 63 (1813) Pinus pseudohalepensis Denhardt ex Carrière, Traité Gén. Conif. 400 (1855). [8] Aleppo pine, Jerusalem pine, halepensis pine, pine [8]. Biology The Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis Mill.) is a medium sized 25 - 30 metre tall, coniferous tree species. The needle like leaves are 6- 10 cm long, bright green and arranged in pairs. Conifers typically produce male and female cones that are retained in the trees canopy. -

Pine As Fast Food: Foraging Ecology of an Endangered Cockatoo in a Forestry Landscape

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Online @ ECU Edith Cowan University Research Online ECU Publications 2013 2013 Pine as Fast Food: Foraging Ecology of an Endangered Cockatoo in a Forestry Landscape William Stock Edith Cowan University, [email protected] Hugh Finn Jackson Parker Ken Dods Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks2013 Part of the Forest Biology Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons 10.1371/journal.pone.0061145 Stock, W.D., Finn, H. , Parker, J., & Dods, K. (2013). Pine as fast food: foraging ecology of an endangered cockatoo in a forestry landscape. PLoS ONE, 8(4), e61145. Availablehere This Journal Article is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks2013/1 Pine as Fast Food: Foraging Ecology of an Endangered Cockatoo in a Forestry Landscape William D. Stock1*, Hugh Finn2, Jackson Parker3, Ken Dods4 1 Centre for Ecosystem Management, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, Western Australia, Australia, 2 School of Biological Sciences and Biotechnology, Murdoch University, Perth, Western Australia, Australia, 3 Department of Agriculture and Food, Western Australia, South Perth, Western Australia, Australia, 4 ChemCentre, Bentley, Western Australia, Australia Abstract Pine plantations near Perth, Western Australia have provided an important food source for endangered Carnaby’s Cockatoos (Calyptorhynchus latirostris) since the 1940s. Plans to harvest these plantations without re-planting will remove this food source by 2031 or earlier. To assess the impact of pine removal, we studied the ecological association between Carnaby’s Cockatoos and pine using behavioural, nutritional, and phenological data. -

Contrasting Effects of Fire Severity on the Regeneration of Pinus Halepensis Mill

Article Contrasting Effects of Fire Severity on the Regeneration of Pinus halepensis Mill. and Resprouter Species in Recently Thinned Thickets Ruth García‐Jiménez, Marina Palmero‐Iniesta and Josep Maria Espelta * CREAF, Cerdanyola del Vallès, Catalonia 08193, Spain; [email protected] (R.G.‐J.); [email protected] (M.P.‐I.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: + 34‐9358‐1467‐1 Academic Editors: Xavier Úbeda and Victoria Arcenegui Received: 23 December 2016; Accepted: 21 February 2017; Published: 24 February 2017 Abstract: Many studies have outlined the benefits for growth and reproduction resulting from thinning extremely crowded young forests regenerating after stand replacing wildfires (“thickets”). However, scarce information is available on how thinning may influence fire severity and vegetation regeneration in case a new fire occurs. We investigated the relationship between thinning and fire severity in P. halepensis thickets, and the effects on the establishment of pine seedlings and resprouting vigour in resprouter species the year after the fire. Our results show a positive relationship between forest basal area and fire severity, and thus reserved pines in thinned stands suffered less fire damage than those in un‐thinned sites (respectively, 2.02 ± 0.13 vs. 2.93 ± 0.15 in a scale from 0 to 4). Ultimately, differences in fire severity influenced post‐fire regeneration. Resprouting vigour varied depending on the species and the size of individuals but it was consistently higher in thinned stands. Concerning P. halepensis, the proportion of cones surviving the fire decreased with fire severity. However, this could not compensate the much lower pine density in thinned stands and thus the overall seed crop was higher in un‐thinned areas. -

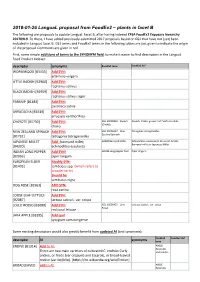

2018-01-26 Langual Proposal from Foodex2 – Plants in Facet B

2018-01-26 LanguaL proposal from FoodEx2 – plants in facet B The following are proposals to update LanguaL Facet B, after having indexed EFSA FoodEx2 Exposure hierarchy 20170919. To these, I have added previously-submitted 2017 proposals based on GS1 that have not (yet) been included in LanguaL facet B. GS1 terms and FoodEx2 terms in the following tables are just given to indicate the origin of the proposal. Comments are given in red. First, some simple additions of terms to the SYNONYM field, to make it easier to find descriptors in the LanguaL Food Product Indexer: descriptor synonyms FoodEx2 term FoodEx2 def WORMWOOD [B3433] Add SYN: artemisia vulgaris LITTLE RADISH [B2960] Add SYN: raphanus sativus BLACK RADISH [B2959] Add SYN: raphanus sativus niger PARSNIP [B1483] Add SYN: pastinaca sativa ARRACACHA [B3439] Add SYN: arracacia xanthorrhiza CHAYOTE [B1730] Add SYN: GS1 10006356 - Squash Squash, Choko, grown from Sechium edule (Choko) choko NEW ZEALAND SPINACH Add SYN: GS1 10006427 - New- Tetragonia tetragonoides Zealand Spinach [B1732] tetragonia tetragonoides JAPANESE MILLET Add : barnyard millet; A000Z Barnyard millet Echinochloa esculenta (A. Braun) H. Scholz, Barnyard millet or Japanese Millet. [B4320] echinochloa esculenta INDIAN LONG PEPPER Add SYN! A019B Long pepper fruit Piper longum [B2956] piper longum EUROPEAN ELDER Modify SYN: [B1403] sambucus spp. (which refers to broader term) Should be sambucus nigra DOG ROSE [B2961] ADD SYN: rosa canina LOOSE LEAF LETTUCE Add SYN: [B2087] lactusa sativa L. var. crispa LOLLO ROSSO [B2088] Add SYN: GS1 10006425 - Lollo Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa Rosso red coral lettuce JAVA APPLE [B3395] Add syn! syzygium samarangense Some existing descriptors would also greatly benefit from updated AI (and synonyms): FoodEx2 FoodEx2 def descriptor AI synonyms term ENDIVE [B1314] Add to AI: A00LD Escaroles There are two main varieties of cultivated C. -

'Wild Harvest in Time of New Pests, Diseases and Climate Change'

Wild harvested nuts and berries in times of new pests, diseases and climate change Round 2 Interregional Workshop of the Wild nuts and berries iNet 12-14, June, Palencia, Spain (& fieldtrips) 1. AGENDA ............................................................................................................................ 1 2. iNet THEMES AND KNOWLEDGE GAPS ............................................................................... 4 3. ATTENDEES ....................................................................................................................... 4 4. WORKSHOP ...................................................................................................................... 5 4.1. Presentations ................................................................................................................ 5 4.2. Work group sessions ...................................................................................................... 8 4.3. Field trips ...................................................................................................................... 10 5. CONCLUSIONS ................................................................................................................ 11 References ......................................................................................................................... 12 1. AGENDA The scoping seminar of the Wild nuts and berries iNet put forward priorities themes to focus INCREDIBLE actions. One of the topics highlighted was the “Long-term resource -

Herbs, Spices and Essential Oils

Printed in Austria V.05-91153—March 2006—300 Herbs, spices and essential oils Post-harvest operations in developing countries UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria Telephone: (+43-1) 26026-0, Fax: (+43-1) 26926-69 UNITED NATIONS FOOD AND AGRICULTURE E-mail: [email protected], Internet: http://www.unido.org INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION OF THE ORGANIZATION UNITED NATIONS © UNIDO and FAO 2005 — First published 2005 All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to: - the Director, Agro-Industries and Sectoral Support Branch, UNIDO, Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria or by e-mail to [email protected] - the Chief, Publishing Management Service, Information Division, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to [email protected] The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization or of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

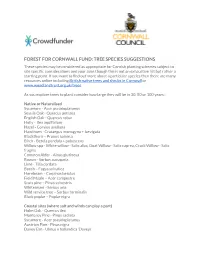

Tree Species Suggestion List

FOREST FOR CORNWALL FUND: TREE SPECIES SUGGESTIONS These species may be considered as appropriate for Cornish planting schemes subject to site specific considerations and your aims though this is not an exhaustive list but rather a starting point. If you want to find out more about a particular species then there are many resources online including British native trees and shrubs in Cornwall or www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/trees As you explore trees to plant consider how large they will be in 30, 50 or 100 years : Native or Naturalised Sycamore - Acer pseudoplatanus Sessile Oak - Quercus petraea English Oak - Quercus robur Holly - Ilex aquifolium Hazel - Corylus avellana Hawthorn - Crataegus monogyna + laevigata Blackthorn – Prunus spinosa Birch - Betula pendula + pubescens Willow spp - White willow - Salix alba, Goat Willow - Salix caprea, Crack Willow - Salix fragilis Common Alder - Alnus glutinosa Rowan - Sorbus aucuparia Lime - Tilia cordata Beech – Fagus sylvatica Hornbeam - Carpinus betulus Field Maple – Acer campestre Scots pine – Pinus sylvestris Whitebeam –Sorbus aria Wild service tree – Sorbus torminalis Black poplar – Poplar nigra Coastal sites (where salt and winds can play a part) Holm Oak - Quercus ilex Monterey Pine - Pinus radiata Sycamore - Acer pseudoplatanus Austrian Pine - Pinus nigra Davey Elm - Ulmus x hollandica ‘Daveyi’ Maritime pine - Pinus pinaster Non-natives for amenity and landscape planting Birch - Betula spp Swamp Cypress - Taxodium distichum Dawn Redwood - Metasequoia glyptostroboides Plane - Platanus occidentalis -

Edible Seeds

List of edible seeds This list of edible seeds includes seeds that are directly 1 Cereals foodstuffs, rather than yielding derived products. See also: Category:Cereals True cereals are the seeds of certain species of grass. Quinoa, a pseudocereal Maize A variety of species can provide edible seeds. Of the six major plant parts, seeds are the dominant source of human calories and protein.[1] The other five major plant parts are roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits. Most ed- ible seeds are angiosperms, but a few are gymnosperms. The most important global seed food source, by weight, is cereals, followed by legumes, and nuts.[2] The list is divided into the following categories: • Cereals (or grains) are grass-like crops that are har- vested for their dry seeds. These seeds are often ground to make flour. Cereals provide almost half of all calories consumed in the world.[3] Botanically, true cereals are members of the Poaceae, the true grass family. A mixture of rices, including brown, white, red indica and wild rice (Zizania species) • Pseudocereals are cereal crops that are not Maize, wheat, and rice account for about half of the grasses. calories consumed by people every year.[3] Grains can be ground into flour for bread, cake, noodles, and other • Legumes including beans and other protein-rich food products. They can also be boiled or steamed, ei- soft seeds. ther whole or ground, and eaten as is. Many cereals are present or past staple foods, providing a large fraction of the calories in the places that they are eaten. -

Identifying Ritual Deposition of Plant Remains: a Case Study of Stone Pine Cones in Roman Britain

Identifying ritual deposition of plant remains: a case study of stone pine cones in Roman Britain Book or Report Section Accepted Version Lodwick, L. (2015) Identifying ritual deposition of plant remains: a case study of stone pine cones in Roman Britain. In: Brindle, T., Allen, M., Durham, E. and Smith, A. (eds.) TRAC 2014: Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference. Oxbow, Oxford, pp. 54-69. ISBN 9781785700026 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/54473/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: Oxbow All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Identifying Ritual Deposition of Plant Remains: a Case Study of Stone Pine Cones in Roman Britain Introduction The identification and theorisation of ritualised deposition in the Roman world has received significant research focus over the last decade (Fulford 2001; Smith 2001). Yet, as within other theory-heavy areas of Roman archaeology (Pitts 2007), plant remains have been poorly integrated into key synthetic works. Analysis has instead focussed on artefactual and zooarchaeological remains (Smith 2001; Morris 2010), with plant remains only briefly alluded to, or discussed largely within specialist archaeobotanical literature (Robinson 2002; Vandorpe and Jacomet 2011). Whilst there is growing evidence for the use of plants in non-funerary classical Roman religion, as well as structured-deposition in shafts and pits, the absence of systematic methodologies and contextual analysis limits the study of ritual plant use in the Roman world. -

Fact Sheet: Pinus Halepensis

Design Standards for Urban Infrastructure Plant Species for Urban Landscape Projects in Canberra Botanical Name: Pinus halepensis (PIh) Common Name: Aleppo pine Species Description • Evergreen • Bushy conifer with narrow, compact growth and a dense crown, shedding lower branches with age; often has a windswept appearance • Reddish-brown, furrowed bark • Slender yellowish-green needles 6 to 10 centimetres long, held in fascicles of two and often curved and twisted 15-20m • Insignificant flowers • Cones held in clusters and point downwards and are bent back along the stem; glossy red-brown when ripe Height and width 15 to 20 metres tall by 12 metres wide Species origin Mediterranean region (Greece and Israel to Spain and 12m Morocco) Landscape use • Available Soil Volume required: ≥70m3 • Can be used in urban parks; provides good shade and useful as a windbreak • The lone pine of ANZAC tradition • Should not be planted near nature reserves, creeks or watercourses Use considerations • One of the most suitable pines for dry areas • High frost tolerance to minus 10 degrees Celsius, and very high drought tolerant of all pines, being suitable for hot dry areas • Suitable for most soils except light sandy soils; will grow on limestone soils of Canberra and surrounds • Long lived • Moderate growth rate • Moderate flammability • Produces pollen and seeds; attracts birds • Cone drop may be a nuisance in pedestrian areas Examples in Canberra Westbourne Woods, National Arboretum Canberra and the entrance to Government House Availability Wholesale conifer nurseries and NSW Forestry Commission .