Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths: Early Childhood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHALLENGING CASES: BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL PEDIATRICS Failure to Thrive in a 4-Month-Old Nursing Infant

CHALLENGING CASES: BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL PEDIATRICS Failure to Thrive in a 4-Month-Old Nursing Infant* CASE visits she was observed to respond quickly to visual Christine, a 4-month-old infant, is brought to the and auditory cues. There was no family history of office for a health-supervision visit by her mother, serious diseases. a 30-year-old emergency department nurse. The In that a comprehensive history and physical ex- mother, who is well known to the pediatrician to be amination did not indicate an organic cause, the a competent and attentive caregiver, appears unchar- pediatrician reasoned that the most likely cause of acteristically tired. They are accompanied by the 18- her failure to thrive was an unintentional caloric month-old and 4-year-old siblings because child care deprivation secondary to maternal stress and ex- was unavailable, and her husband has been out of haustion. Christine’s mother and the pediatrician town on business for the last 5 weeks. When the discussed how maternal stress, fatigue, and depres- pediatrician comments, “You look exhausted. It must sion could hinder the let-down reflex and reduce the be really tough to care for 3 young children,” the availability of an adequate milk supply, as well as mother appears relieved that attention was given to make it difficult to maintain regular feeding sessions. her needs. She reports that she has not been getting The pediatrician recommended obtaining help with much sleep because Christine wakes up for 2 or more child care and household responsibilities. The evening feedings and the toddler is now awakening mother was also encouraged to consume adequate at night. -

A Dose-Response Relationship Between Organic Mercury Exposure from Thimerosal-Containing Vaccines and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 9156-9170; doi:10.3390/ijerph110909156 OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health ISSN 1660-4601 www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph Article A Dose-Response Relationship between Organic Mercury Exposure from Thimerosal-Containing Vaccines and Neurodevelopmental Disorders David A. Geier 1, Brian S. Hooker 2, Janet K. Kern 1,3, Paul G. King 4, Lisa K. Sykes 4 and Mark R. Geier 1,* 1 Institute of Chronic Illnesses, Inc., 14 Redgate Ct., Silver Spring, MD 20905, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (D.A.G.); [email protected] (J.K.K.) 2 Department of Biology, Simpson University, 2211 College View Dr., Redding, CA 96003, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, 5353 Harry Hine Blvd., Dallas, TX 75390, USA 4 CoMeD, Inc., 14 Redgate Ct., Silver Spring, MD 20905, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (P.G.K.); [email protected] (L.K.S.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-301-989-0548; Fax: +1-301-989-1543. Received: 12 July 2014; in revised form: 7 August 2014 / Accepted: 26 August 2014 / Published: 5 September 2014 Abstract: A hypothesis testing case-control study evaluated concerns about the toxic effects of organic-mercury (Hg) exposure from thimerosal-containing (49.55% Hg by weight) vaccines on the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDs). Automated medical records were examined to identify cases and controls enrolled from their date-of-birth (1991–2000) in the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) project. -

Intervention Ideas for Infants, Toddlers, Children, and Youth Impacted by Opioids

TOPICAL ISSUE BRIEF Intervention IDEAs for Infants, Toddlers, Children, and Youth Impacted by Opioids Overview Prevalence The abuse of opioids—such as heroin and various prescription drugs commonly prescribed for pain (e.g., oxycodone, hydrocodone, and fentanyl)—has rapidly gained attention across the United States as a public health crisis. Youth may be exposed to opioids in a variety of ways, including but not limited to infants born to mothers who took opioids during pregnancy; children mistakenly consuming opioids (perhaps thinking they are candy); teenagers taking opioids from an illicit street supply; or, more commonly, teenagers being given opiates for free by a friend or relative.1,2 Even appropriate opioid use among adolescents and young adults to treat pain may slightly increase their risk of later opioid misuse.3 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have identified opioid abuse as an epidemic, noting that opioids impact and affect all communities and age groups.4 Between 1997 and 2012, 13,052 children were hospitalized for poisonings caused by oxycodone, Percocet (a combination of acetaminophen and oxycodone), codeine, and other prescription opioids.5 Every 25 minutes, an infant is born suffering from opioid withdrawal, and an estimated 21,732 infants were born in 2012 with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), a drug withdrawal syndrome.6 According to data from 2014, approximately 28,000 adolescents had used heroin within the past year, 16,000 were current heroin users, and 18,000 had a heroin use disorder.7 At the same time, relatively few data are available about the effects of opiates on the U.S. -

The Child with Failure to Thrive

The Child with Failure to Thrive Bonnie Proulx, MSN, APRN, PNP Pediatric Gastroenterology Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth Manchester, NH DISCLOSURES None of the planners or presenters of this session have disclosed any conflict or commercial interest The Child with Failure to Thrive OBJECTIVES: 1. Review assessment and appropriate diagnostic testing for children who fail meet expected growth 2. Discuss various causes of failure to thrive. 3. Identify appropriate referrals for children with failure to thrive. Definition • Inadequate physical growth diagnosed by observation of growth over time on a standard growth chart Definition • More than 2 standard deviations below mean for age • Downward trend in growth crossing 2 major percentiles in a short time • Comparison of height and weight • Not a diagnosis but a finding Pitfalls • Some children are just tiny • Familial short stature children may cross percentiles to follow genetic predisposition • Normal small children may be diagnosed later given already tiny Frequency • Affects 5-10% of children under 5 in developing countries • Peak incidence between 9 and 24 months of age • Uncommon after the age of 5 What is normal growth • Birth to 6 months, a baby may grow 1/2 to 1 inch (about 1.5 to 2.5 centimeters) a month • 6 to 12 months, a baby may grow 3/8 inch (about 1 centimeter) a month • 2nd year of life 4-6 inches • 3rd year 3-4 inches • Annual growth until pre-puberty 2-3 inches per year Normal weight gain • Birth to 6 months-gain 5 to 7 ounces a week. • 6 to 12 months -gain 3 to 5 ounces (about 85 to 140 grams) a week. -

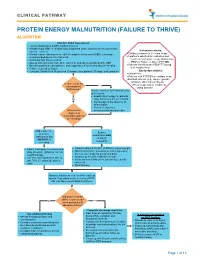

Protein Energy Malnutrition (Failure to Thrive) Algorithm

CLINICAL PATHWAY PROTEIN ENERGY MALNUTRITION (FAILURE TO THRIVE) ALGORITHM Conduct Initial Assessment • History and physical (H&P), nutrition focused • Weight height, BMI, % of ideal body weight and exam: assess severity (symmetric edema = severe) Inclusion criteria: • • Consider basic labs based on H&P; A complete blood count (CBC) is strongly Children newborn to 21 years of age • recommended due to risk of anemia Inpatients admitted for evaluation and • Additional labs based on H&P treatment of Protein Energy Malnutrition • Assess micronutrients: iron, zinc, vitamin D, and others as indicated by H&P (PEM) or Failure to thrive (FTT) OR • • Baseline potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium if concerned about re-feeding Patients identified with PEM/FTT during • Calorie count up to 3 days their hospital stay. • Consults: Social Work, Registered Dietician, Occupational Therapy, and Lactation Exclusion criteria: • Outpatients • Patients with FTT/PEM secondary to an identified concern (e.g., cancer, genetic condition, other chronic illness). Is there a risk for •Pts w/ suspected or confirmed micronutrient Yes eating disorder deficiencies? Initiate treatment for micronutrients deficiencies: • Empiric zinc therapy for patients No older than 6 months for 1 month • Iron therapy in the absence of inflammation • Vitamin D and other What are the micronutrients based on labs degrees of malnutrition and risk of refeeding? Mild, moderate, Severe or severe malnutrition AND malnutrition but at risk of NO RISK of refeeding refeeding • • Initiate feeding per recommended Initiate feeding at 30-50% of RDA for current weight • daily allowance (RDA) for current Monitor potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium weight and age once to twice a day for a total of 4 days • • Use PO route if patient is able to Advance by 10-20% if labs are normal • take 70% of estimated calories If labs abnormal hold off on advancing feed until orally corrected • Start thiamine Advance calories to meet level for catch up growth. -

Parenting Children Who Have Been Exposed to Methamphetamine

Non-Return Information Packet Assisting families on their lifelong journey Parenting Children Who Have Been Exposed to Methamphetamine A Brief Guide for Adoptive, Guardianship, and Foster Parents Oregon Post Adoption Resource Center 2950 SE Stark Street, Suite 130 Portland, Oregon 97214 503-241-0799 800-764-8367 503-241-0925 Fax [email protected] www.orparc.org ORPARC is a contracted service of the Oregon Department of Human Services. Please do not reproduce without permission. PARENTING CHILDREN WHO HAVE BEEN EXPOSED TO METHAMPHETAMINE A BRIEF GUIDE FOR ADOPTIVE, GUARDIANSHIP AND FOSTER PARENTS Table of Contents Introduction: ............................................................................................................. 1 Part I: Methamphetamine: An Overview ........................................................... 2 What is meth? What are its effects on the user? How prevalent is meth use? How is meth addiction treated? Part II: Meth’s Effects on Children ...................................................................... 7 What are the prenatal effects of exposure? What are the postnatal effects of prenatal exposure? What are the environmental effects on children? Part III: Parenting Meth-Exposed Children ....................................................... 11 Guiding principles Age-specific suggestions Part IV: Reprinted Articles .................................................................................. 20 Appendix A: Recommended Resources Appendix B: Sources Page i PARENTING CHILDREN WHO HAVE -

Prenatal Cocaine Exposure and Infant Cognition

Infant Behavior & Development 28 (2005) 431–444 Prenatal cocaine exposure and infant cognition Lynn T. Singer a,∗, Laurie J. Eisengart a, Sonia Minnes a, Julia Noland b, Arthur Jey a, Courtney Lane a, Meeyoung O. Min a a Department of Pediatrics, Case Western Reserve University, The Triangle Building, 11400 Euclid Avenue, Suite 250-A, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA b Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA Received 9 November 2004; received in revised form 8 March 2005; accepted 24 March 2005 Abstract The present study examined the relationship of prenatal cocaine exposure to infant information processing in the first year of life. In a prospective, longitudinal study of 177 cocaine-exposed and 175 non-exposed infants, the Fagan Test of Infant Intelligence (FTII) was used to measure attention, visual recognition memory and information processing speed at 6.5 and 12 months of age. Groups were compared over time using mixed linear model analyses. Prenatal cocaine exposure predicted poorer visual recognition memory at 12 months, with exposed infants ob- taining lower mean scores and a higher percentage of scores in the risk range. Across exposure groups, information processing speed increased with age, demonstrating a developmental effect. Tobacco and marijuana exposures were related to faster looking times, which did not relate to visual recognition memory. Cognitive deficits and attentional problems noted in prior studies of cocaine-exposed children at later ages may be detectable in infancy. © 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: Cocaine; Infants; Visual recognition; Memory; Fagan Test of Infant Intelligence 1. Introduction During the 1980s, cocaine use reached epidemic levels in the United States among pregnant women in urban areas, subsequently exposing hundreds of thousands of children to cocaine prenatally (National ∗ Corresponding author. -

Paediatrics at a Glance

Paediatrics at a Glance Lawrence Miall Mary Rudolf Malcolm Levene Blackwell Science Paediatrics at a Glance This book is dedicated to our children Charlie, Mollie, Rosie Aaron, Rebecca Alysa, Katie, Ilana, Hannah, David and all those children who enlightened and enlivened us during our working lives. Paediatrics at a Glance LAWRENCE MIALL MB BS, BSc, MMedSc, MRCP, FRCPCH Consultant Neonatologist and Honorary Senior Lecturer Neonatal Intensive Care Unit St James’s University Hospital Leeds MARY RUDOLF MB BS BSc DCH FRCPCH FAAP Consultant Paeditrician in Community Child Health Leeds Community Children’s Services Belmont House Leeds MALCOLM LEVENE MD FRCP FRCPCH FMedSc Professor of Paediatrics School of Medicine Leeds General Infirmary Leeds Blackwell Science © 2003 by Blackwell Science Ltd a Blackwell Publishing company Blackwell Science, Inc., 350 Main Street, Malden, Massachusetts 02148-5018, USA Blackwell Science Ltd, Osney Mead, Oxford OX2 0EL, UK Blackwell Science Asia Pty Ltd, 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia Blackwell Wissenschafts Verlag, Kurfürstendamm 57, 10707 Berlin, Germany The right of the Authors to be identified as the Authors of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2003 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Miall, Lawrence. Paediatrics at a glance/Lawrence Miall, Mary Rudolf, Malcolm Levene. -

Validity and Reliability of Clinical Signs in the Diagnosis of Dehydration in Children

Validity and Reliability of Clinical Signs in the Diagnosis of Dehydration in Children Marc H. Gorelick, MD, MS*§; Kathy N. Shaw, MD, MS*§; and Kathleen O. Murphy, RN, MSN‡ ABSTRACT. Objective. To determine the validity and Children with acute gastroenteritis or other ill- reliability of various clinical findings in the diagnosis of nesses that cause vomiting, diarrhea, or poor oral dehydration in children. fluid intake are at risk for developing dehydration. Design. Prospective cohort study. The gold standard for diagnosis of dehydration is Setting. An urban pediatric hospital emergency measurement of acute weight loss. Because a pa- department. tient’s true preillness weight is rarely known in the Participants. One hundred eighty-six children ranging in age from 1 month to 5 years old with diarrhea, vomiting, acute care setting, an estimate of the fluid deficit is or poor oral fluid intake, either admitted or followed as made based on clinical assessment. This estimate is outpatients. Exclusion criteria included malnutrition, recent used to determine the need for therapy and the type prior therapy at another facility, symptoms for longer than of therapy to be used, and to monitor the patient’s 5 days’ duration, and hyponatremia or hypernatremia. response to treatment. Failure to recognize dehydra- Methods. All children were evaluated for 10 clinical tion leads to increased morbidity and mortality, signs before treatment. The diagnostic standard for de- while overdiagnosis can result in overutilization of hydration was fluid deficit as determined from serial health resources.1–4 weight gain after treatment. Conventionally used clinical diagnostic criteria for . Sixty-three children (34%) had dehy- Main Results evaluating dehydration have been codified by the dration, defined as a deficit of 5% or more of body 5 weight. -

Development of Infants and Toddlers Exposed to Cocaine Cynthia Denson

Cardinal Stritch University Stritch Shares Master's Theses, Capstones, and Projects 1-1-1991 Development of infants and toddlers exposed to cocaine Cynthia Denson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.stritch.edu/etd Part of the Special Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Denson, Cynthia, "Development of infants and toddlers exposed to cocaine" (1991). Master's Theses, Capstones, and Projects. 974. https://digitalcommons.stritch.edu/etd/974 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by Stritch Shares. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses, Capstones, and Projects by an authorized administrator of Stritch Shares. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEVELOPMENT OF INFANTS AND TODDLERS EXPOSED TO COCAINE by Cynthia Denson A RESEARCH PAPER SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN EDUCATION (SPECIAL EDUCATION) AT CARDINAL STRITCH COLLEGE Milwaukee, Wisconsin 1991 1t..1 2 This research paper has been approved for the Graduate Committee of the Cardinal Stritch College by Date ~ t·. , 3 Acknowledgements To my husband, Ralph, and to my children Brittany, Carissa and Jed. You are the wind beneath my wings. 4 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 CHAPTER I 7 Introduction 7 Purpose of the study 8 Scope and Limitation 9 Definitions 9 Summary 12 CHAPTER I I 13 Wha tis Coca i ne ? 13 uterine and Intrauterine Effects of 15 Cocaine Neonatal Manifestations 18 Characteristics of Infants Exposed to 25 Cocaine Abnormalities -

The Offspring of Alcoholic Mothers

THE OFFSPRING OF ALCOHOLIC MOTHERS Christy N. Ulleland Harborview Medical Center Seattle, Washington 98104 From October 1968 through June 1969 we observed six infants at the Univer- sity of Washington’s Harborview Medical Center who had three features in com- mon. First, Each of these infants was born undergrown for gestational age, with a birth weight below the tenth percentile, by Lubchenco’s standards. Second, their postnatal growth and development did not proceed at a normal rate. Four were admitted to the hospital in the first six months of life because of failure to thrive and did not grow there in spite of special attention given to their feeding and care. Finally, the mothers of all these infants were chronic alcoholics as defined by Keller’s modification of the World Health Organization definition. Alcoholism is defined as a chronic behavioral disorder manifested by repeated drinking of alcoholic beverages in excess of the dietary and social uses of the community and to an extent that interferes with the drinker’s health or his social or economic function. The observation of this triad led us to examine our experience with infants undergrown for gestational age, infants under one year of age who had been admitted to the hospital for failure to thrive, and alcoholic women who had delivered at our institution. The newborn nursery and delivery records were reviewed to identify all undergrown infants born in the 18-month period January 1, 1968, through June 30, 1969. This period included the birthdates of the six index cases. The records of infants less than one year of age hospitalized with a diagnosis of failure to thrive in the same 18-month period were also reviewed. -

Assessment of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome: Standard Scoring of Infants Using the Finnegan Scoring Tool

Assessment of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome: Standard Scoring of Infants using the Finnegan Scoring Tool Welcome to Assessment of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome - Standard Scoring of Newborns using the Modified Finnegan Scoring Tool • This Computer Based Learning (CBL) Module is designed to be used as a self study guide. • The goal of this self study guide is to improve our care of babies at risk for NAS by improving the consistency with which we score these babies. • This CBL includes some basic information about NAS and step by step instructions for using the Modified Finnegan Scoring Tool Part 1: Facing the Problem • Drug use in women is an increasingly important problem in our society. Although reports of drug use are generally lower among pregnant women than non- pregnant women, it has been reported that among pregnant women ages 15-44: – 4.5% report use of illicit drugs – 11.9% report binge or heavy drinking – 15.3 report tobacco use Newborn Exposures • Drug use among pregnant women can lead to problems in the developing fetus including congenital anomalies, problems with growth, preterm labor, withdrawal or toxicity in the newborn, and later problems with neurodevelopment. One of the most readily apparent problems created by in utero exposure to drugs is neonatal abstinence syndrome. Like the rates of maternal drug use, the rates of neonatal abstinence syndrome are increasing • Number of infants coded at discharge with NAS – 7,653 in 1995 – 11,937 in 2008 Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome • Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) describes withdrawal of the newborn from drugs that the mother was taking during pregnancy.