Paediatrics at a Glance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHALLENGING CASES: BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL PEDIATRICS Failure to Thrive in a 4-Month-Old Nursing Infant

CHALLENGING CASES: BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL PEDIATRICS Failure to Thrive in a 4-Month-Old Nursing Infant* CASE visits she was observed to respond quickly to visual Christine, a 4-month-old infant, is brought to the and auditory cues. There was no family history of office for a health-supervision visit by her mother, serious diseases. a 30-year-old emergency department nurse. The In that a comprehensive history and physical ex- mother, who is well known to the pediatrician to be amination did not indicate an organic cause, the a competent and attentive caregiver, appears unchar- pediatrician reasoned that the most likely cause of acteristically tired. They are accompanied by the 18- her failure to thrive was an unintentional caloric month-old and 4-year-old siblings because child care deprivation secondary to maternal stress and ex- was unavailable, and her husband has been out of haustion. Christine’s mother and the pediatrician town on business for the last 5 weeks. When the discussed how maternal stress, fatigue, and depres- pediatrician comments, “You look exhausted. It must sion could hinder the let-down reflex and reduce the be really tough to care for 3 young children,” the availability of an adequate milk supply, as well as mother appears relieved that attention was given to make it difficult to maintain regular feeding sessions. her needs. She reports that she has not been getting The pediatrician recommended obtaining help with much sleep because Christine wakes up for 2 or more child care and household responsibilities. The evening feedings and the toddler is now awakening mother was also encouraged to consume adequate at night. -

A Dose-Response Relationship Between Organic Mercury Exposure from Thimerosal-Containing Vaccines and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 9156-9170; doi:10.3390/ijerph110909156 OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health ISSN 1660-4601 www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph Article A Dose-Response Relationship between Organic Mercury Exposure from Thimerosal-Containing Vaccines and Neurodevelopmental Disorders David A. Geier 1, Brian S. Hooker 2, Janet K. Kern 1,3, Paul G. King 4, Lisa K. Sykes 4 and Mark R. Geier 1,* 1 Institute of Chronic Illnesses, Inc., 14 Redgate Ct., Silver Spring, MD 20905, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (D.A.G.); [email protected] (J.K.K.) 2 Department of Biology, Simpson University, 2211 College View Dr., Redding, CA 96003, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, 5353 Harry Hine Blvd., Dallas, TX 75390, USA 4 CoMeD, Inc., 14 Redgate Ct., Silver Spring, MD 20905, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (P.G.K.); [email protected] (L.K.S.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-301-989-0548; Fax: +1-301-989-1543. Received: 12 July 2014; in revised form: 7 August 2014 / Accepted: 26 August 2014 / Published: 5 September 2014 Abstract: A hypothesis testing case-control study evaluated concerns about the toxic effects of organic-mercury (Hg) exposure from thimerosal-containing (49.55% Hg by weight) vaccines on the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDs). Automated medical records were examined to identify cases and controls enrolled from their date-of-birth (1991–2000) in the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) project. -

Guiding Principles for Complementary Feeding of the Breastfed Infant

GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR COMPLEMENTARY FEEDING OF THE BREASTFED CHILD PAN AMERICAN HEALTH ORGANIZATION WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION Division of Health Promotion and Protection Celebrating 100 Years of Health Food and Nutrition Program GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR COMPLEMENTARY FEEDING OF THE BREASTFED CHILD TABLE OF CONTENTS 8 Introduction 10 Duration of exclusive breastfeeding and age of introduction of complementary foods 12 Maintenance of breastfeeding 14 Responsive feeding 16 Safe preparation and storage of complementary foods 18 Amount of complementary food needed 20 Food consistency 21 Meal frequency and energy density 22 Nutrient content of complementary foods 25 Use of vitamin-mineral supplements or fortified products for infant and mother 26 Feeding during and after illness 28 Use of these Guiding Principles Food and Nutrition 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document was written by Kathryn Dewey. Chessa Lutter was the responsible technical officer and provided comments and technical oversight. Jose Martines and Bernadette Daelmans provided extensive comments. An earlier draft was reviewed and commented on by the par- ticipants at the WHO Global Consultation on Complementary Feeding, December 10-13, 2001. TABLES 33 Table 1: Minimum number of meals required to attain the level of energy needed from complementary foods with mean energy density of 0.6, 0.8, or 1.0 kcal/g for children in developing countries with low or average levels of breast milk energy intake (BME), by age and group. 33 Table 2: Minimum dietary energy density (kcal/g) required to -

Your 2 Week Infant

YOUR 2 WEEK INFANT For any fever over 100.5 your baby needs to be examined and may need to have blood and urine evaluated for infection. Other signs of infection might be: If your baby is lethargic, less responsive than usual, or floppy when you hold her, If your baby is very irritable and you cannot console him, If your baby refuses to eat or has no wet diapers in 24 hours. If any of these occur or if you discover your baby has a temperature, rectally or under the arm, higher than 100.5 degrees, call our office right away. Your baby should have NO Tylenol, Motrin, or any other pain reliever in the first two months of life so as not to mask any fever. Keep your baby away from large groups of people and small children in which there is a risk someone may be sick and transmit an infection to your infant. Ask family members to wash their hands before holding your baby. Back to sleep. Your baby should sleep on his back to help protect him from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). You can also protect your baby by not smoking around him. Be sure to give your baby tummy time for at least 15-20 minutes while he is awake to work on developmental skills and build strong back muscles. Your baby should ride in a carseat each time she is in a motor vehicle. The carseat should face the back of the car until the baby is one year old and reaches 20 pounds. -

Intervention Ideas for Infants, Toddlers, Children, and Youth Impacted by Opioids

TOPICAL ISSUE BRIEF Intervention IDEAs for Infants, Toddlers, Children, and Youth Impacted by Opioids Overview Prevalence The abuse of opioids—such as heroin and various prescription drugs commonly prescribed for pain (e.g., oxycodone, hydrocodone, and fentanyl)—has rapidly gained attention across the United States as a public health crisis. Youth may be exposed to opioids in a variety of ways, including but not limited to infants born to mothers who took opioids during pregnancy; children mistakenly consuming opioids (perhaps thinking they are candy); teenagers taking opioids from an illicit street supply; or, more commonly, teenagers being given opiates for free by a friend or relative.1,2 Even appropriate opioid use among adolescents and young adults to treat pain may slightly increase their risk of later opioid misuse.3 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have identified opioid abuse as an epidemic, noting that opioids impact and affect all communities and age groups.4 Between 1997 and 2012, 13,052 children were hospitalized for poisonings caused by oxycodone, Percocet (a combination of acetaminophen and oxycodone), codeine, and other prescription opioids.5 Every 25 minutes, an infant is born suffering from opioid withdrawal, and an estimated 21,732 infants were born in 2012 with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), a drug withdrawal syndrome.6 According to data from 2014, approximately 28,000 adolescents had used heroin within the past year, 16,000 were current heroin users, and 18,000 had a heroin use disorder.7 At the same time, relatively few data are available about the effects of opiates on the U.S. -

Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths: Early Childhood

Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths: Early Childhood CANS: EC Supplemental Guide A Support for the CANS (Early Childhood) Information Integration Tool for Young Children Ages Birth to Five SET is part of the System of Care Initiative, within the Allegheny County Department of Human Services, Office of Behavioral Health Stacey Cornett, Copyright 2007. Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths: Early Childhood (CANS:EC) Section One: Child Strengths This section focuses on the attributes, traits, talents and skills of the child that can be useful in developing a strength-based treatment plan. Within a systems of care approach identifying strengths is considered an essential part of the process (Miles, P., Burns, E.J., Osher, T.W., Walker, J.S., 2006). A focus on strengths that both the child and the family have to offer allows for a climate of hope and optimism and has been proven to engage families at a higher level. Strength-based assessment has been defined as, “the measurement of those emotional and behavioral skills, competencies, and characteristics that create a sense of personal accomplishment; contribute to satisfying relationships with family members, peers, and adults; enhance one’s ability to deal with adversity and stress; and promote one’s personal, social, and academic development” (Epstein & Sharma, 1998, p.3). The benefits of a strength- based assessment include involving parents and children in a service planning experience that builds on what a child and family are doing well, facilitates positive expectations for the child, and empowers family members to take responsibility for the decisions that will affect their child (Johnson & Friedman, 1991; Saleebey, 1992). -

The Child with Failure to Thrive

The Child with Failure to Thrive Bonnie Proulx, MSN, APRN, PNP Pediatric Gastroenterology Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth Manchester, NH DISCLOSURES None of the planners or presenters of this session have disclosed any conflict or commercial interest The Child with Failure to Thrive OBJECTIVES: 1. Review assessment and appropriate diagnostic testing for children who fail meet expected growth 2. Discuss various causes of failure to thrive. 3. Identify appropriate referrals for children with failure to thrive. Definition • Inadequate physical growth diagnosed by observation of growth over time on a standard growth chart Definition • More than 2 standard deviations below mean for age • Downward trend in growth crossing 2 major percentiles in a short time • Comparison of height and weight • Not a diagnosis but a finding Pitfalls • Some children are just tiny • Familial short stature children may cross percentiles to follow genetic predisposition • Normal small children may be diagnosed later given already tiny Frequency • Affects 5-10% of children under 5 in developing countries • Peak incidence between 9 and 24 months of age • Uncommon after the age of 5 What is normal growth • Birth to 6 months, a baby may grow 1/2 to 1 inch (about 1.5 to 2.5 centimeters) a month • 6 to 12 months, a baby may grow 3/8 inch (about 1 centimeter) a month • 2nd year of life 4-6 inches • 3rd year 3-4 inches • Annual growth until pre-puberty 2-3 inches per year Normal weight gain • Birth to 6 months-gain 5 to 7 ounces a week. • 6 to 12 months -gain 3 to 5 ounces (about 85 to 140 grams) a week. -

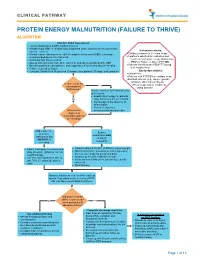

Protein Energy Malnutrition (Failure to Thrive) Algorithm

CLINICAL PATHWAY PROTEIN ENERGY MALNUTRITION (FAILURE TO THRIVE) ALGORITHM Conduct Initial Assessment • History and physical (H&P), nutrition focused • Weight height, BMI, % of ideal body weight and exam: assess severity (symmetric edema = severe) Inclusion criteria: • • Consider basic labs based on H&P; A complete blood count (CBC) is strongly Children newborn to 21 years of age • recommended due to risk of anemia Inpatients admitted for evaluation and • Additional labs based on H&P treatment of Protein Energy Malnutrition • Assess micronutrients: iron, zinc, vitamin D, and others as indicated by H&P (PEM) or Failure to thrive (FTT) OR • • Baseline potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium if concerned about re-feeding Patients identified with PEM/FTT during • Calorie count up to 3 days their hospital stay. • Consults: Social Work, Registered Dietician, Occupational Therapy, and Lactation Exclusion criteria: • Outpatients • Patients with FTT/PEM secondary to an identified concern (e.g., cancer, genetic condition, other chronic illness). Is there a risk for •Pts w/ suspected or confirmed micronutrient Yes eating disorder deficiencies? Initiate treatment for micronutrients deficiencies: • Empiric zinc therapy for patients No older than 6 months for 1 month • Iron therapy in the absence of inflammation • Vitamin D and other What are the micronutrients based on labs degrees of malnutrition and risk of refeeding? Mild, moderate, Severe or severe malnutrition AND malnutrition but at risk of NO RISK of refeeding refeeding • • Initiate feeding per recommended Initiate feeding at 30-50% of RDA for current weight • daily allowance (RDA) for current Monitor potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium weight and age once to twice a day for a total of 4 days • • Use PO route if patient is able to Advance by 10-20% if labs are normal • take 70% of estimated calories If labs abnormal hold off on advancing feed until orally corrected • Start thiamine Advance calories to meet level for catch up growth. -

Bfn How Safe Is?...Alcohol, Smoking, Medicines and Breastfeeding

Alcohol Patient Information Leaflets You do not have to miss out on drinking alcohol whilst you Many patient information leaflets within packets of tablets say “do are breastfeeding even though it passes quite freely into your not take if you are breastfeeding”. This does not necessarily mean breastmilk. There is no evidence that having an occasional drink that they will be harmful to your baby, just that the manufacturer will harm your baby. Alcohol levels are highest about 30-90 has not conducted any trials. Governmental regulations allow them minutes after drinking so you may want to try to restrict your to opt out of taking responsibility for use during breastfeeding. drinking until after your baby has fed. Never put yourself in a If you are concerned please check the Drug Information Factsheets situation where you may fall asleep with your baby (on a bed, section of our website: www.breastfeedingnetwork.org.uk chair or settee) if you have been drinking. If you have had lots or call the Drugs in Breastmilk Helpline to check: to drink (binge drinking) ask someone else to care for 0844 412 4665. your baby as alcohol affects your ability to care safely for your baby, no matter how you are feeding. If you If someone tells you that you can’t continue to pass out or vomit from too much alcohol don’t breastfeed if you have to take a medicine, or breastfeed until the following morning. You do not for any other reason, ask for help. It may not need to express to clear your milk of alcohol as it passes back into your bloodstream as your own blood levels fall. -

Parenting Children Who Have Been Exposed to Methamphetamine

Non-Return Information Packet Assisting families on their lifelong journey Parenting Children Who Have Been Exposed to Methamphetamine A Brief Guide for Adoptive, Guardianship, and Foster Parents Oregon Post Adoption Resource Center 2950 SE Stark Street, Suite 130 Portland, Oregon 97214 503-241-0799 800-764-8367 503-241-0925 Fax [email protected] www.orparc.org ORPARC is a contracted service of the Oregon Department of Human Services. Please do not reproduce without permission. PARENTING CHILDREN WHO HAVE BEEN EXPOSED TO METHAMPHETAMINE A BRIEF GUIDE FOR ADOPTIVE, GUARDIANSHIP AND FOSTER PARENTS Table of Contents Introduction: ............................................................................................................. 1 Part I: Methamphetamine: An Overview ........................................................... 2 What is meth? What are its effects on the user? How prevalent is meth use? How is meth addiction treated? Part II: Meth’s Effects on Children ...................................................................... 7 What are the prenatal effects of exposure? What are the postnatal effects of prenatal exposure? What are the environmental effects on children? Part III: Parenting Meth-Exposed Children ....................................................... 11 Guiding principles Age-specific suggestions Part IV: Reprinted Articles .................................................................................. 20 Appendix A: Recommended Resources Appendix B: Sources Page i PARENTING CHILDREN WHO HAVE -

Bright Futures: Nutrition Supervision

BRIGHT FUTURES: NUTRITION Nutrition Supervision 17 FUTURES Bright BRIGHT FUTURES: NUTRITION Infancy Infancy 19 FUTURES Bright BRIGHT FUTURES: NUTRITION Infancy Infancy CONTEXT Infancy is a period marked by the most rapid growth and physical development experi- enced throughout life. Infancy is divided into several stages, each of which is unique in terms of growth, developmental achievements, nutrition needs, and feeding patterns. The most rapid changes occur in early infancy, between birth and age 6 months. In middle infancy, from ages 6 to 9 months, and in late infancy, from ages 9 to 12 months, growth slows but still remains rapid. During the first year of life, good nutrition is key to infants’ vitality and healthy develop- ment. But feeding infants is more than simply offering food when they are hungry, and it serves purposes beyond supporting their growth. Feeding also provides opportunities for emotional bonding between parents and infants. Feeding practices serve as the foundation for many aspects of family development (ie, all members of the family—parents, grandparents, siblings, and the infant—develop skills in responding appropriately to one another’s cues). These skills include identifying, assessing, and responding to infant cues; promoting reciprocity (infant’s responses to parents, grand- parents, and siblings and parents’, grandparents’, and siblings’ responses to the infant); and building the infant’s feeding and pre-speech skills. When feeding their infant, parents gain a sense of responsibility, experience frustration when they cannot interpret the infant’s cues, and develop the ability to negotiate and solve problems through their interactions with the infant. They also expand their abilities to meet their infant’s needs. -

Alcohol Guidelines for Pregnant Women Barriers and Enablers for Midwives to Deliver Advice

August 2019 Alcohol guidelines for pregnant women Barriers and enablers for midwives to deliver advice Lisa Schölin, Julie Watson, Judith Dyson and Lesley Smith ALCOHOL GUIDELINES FOR PREGNANT WOMEN: BARRIERS AND ENABLERS FOR MIDWIVES TO DELIVER ADVICE Alcohol guidelines for pregnant womeN Barriers and enablers for midwives to deliver advice Authors Lisa Schölin, Julie Watson, Judith Dyson and Lesley Smith. Acknowledgements The authors would like to dedicate this report to Pip Williams, member of the stakeholder group, who sadly passed away before this study was completed. Pip was a strong advocate for FASD birthmothers and those living with FASD themselves and worked incredibly hard to raise awareness of the issues women with lived experience of addiction face. She was an inspiring, strong, dedicated, and compassionate woman and her legacy will continue to inspire people in the field. We are deeply grateful for the input she had in this study and we will miss her. We would also like to acknowledge all midwives who took part in this study, who we know are working under increasingly demanding pressures and still took the time to share their knowledge and experiences of this topic. Finally, we also want to acknowledge the stakeholder group who helped shape this study, supported recruitment, and will help share the results. The authors would also like to thank Professor Linda Bauld, University of Edinburgh, and Clare Livingstone, Royal College of Midwives, for reviewing the report. Image credit: MachineHeadz / iStock. Funding The report was