Regroupment & Refoundation of a U.S. Left

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Could There Be a Corbyn in Australia?

The emancipation of the working class must be the act of the working class itself ISSN 1446-0165 No.67. July 2017 http://australia.workersliberty.org How could there be a Corbyn in Australia? Could there be a political leader who could achieve Corbyn was mostly seen as not particularly leadership success at galvanising a mass movement for the working material. He was reluctant to stand, and thought he class, against capital, as Corbyn has done in Britain? We probably wouldn't get enough nominations. Having run as start by looking at how Corbyn became Labour leader. a flying the flag exercise, he had leadership thrust upon him. The 2008 slump hit Britain much harder than it hit Australia, so there has been more leftish agitation in Britain than Australia in the last 8 years, more sizeable left demonstrations, meetings, campaigns. This created a constituency in Labour Party politics in which the local party organisations swung a little to the left. So one of the preconditions for Corbyn, was the almost invisible revival of some Labour left, and some hope of Labour moving left under Ed Milliband. Ed Milliband as a very soft left leader was an electoral failure. This opened the way for a more serious left challenge to be welcomed by members, in the context of the impact of economic crisis in Britain. Milliband raised expectations, continuing to say leftish things from time to time, so he simultaneously raised hopes and yet disappointed them. After Ed Milliband resigned, all the contenders to replace him competed as to who could be most right wing because they thought that was the way to win. -

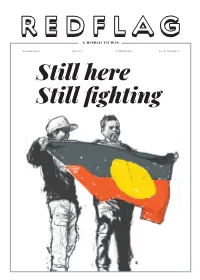

RF177.Pdf (Redflag.Org.Au)

A WORLD TO WIN REDFLAG.ORG.AU ISSUE #177 19 JANUARY 2021 $3 / $5 (SOLIDARITY) Still here Still fi ghting REDFLAG | 19 JANUARY 2021 PUBLICATION OF SOCIALIST ALTERNATIVE REDFLAG.ORG.AU 2 Red Flag Issue # 177 19 January 2021 ISSN: 2202-2228 Published by Red Flag Support the Press Inc. Trades Hall 54 Victoria St Carlton South Vic 3053 [email protected] Christmas Island (03) 9650 3541 Editorial committee Ben Hillier Louise O’Shea Daniel Taylor Corey Oakley rioters James Plested Simone White fail nonetheless. Some are forced to complete rehabil- Visual editor itation programs and told that when they do so their James Plested appeals will be strengthened. They do it. They fail. These are men with families in Australia. They Production are workers who were raising children. They are men Tess Lee Ack n the first week of 2021, detainees at the Christ- who were sending money to impoverished family Allen Myers mas Island Immigration Detention Centre be- members in other countries. Now, with their visas can- Oscar Sterner gan setting it alight. A peaceful protest, which celled, they have no incomes at all. This has rendered Subscriptions started on the afternoon of 5 January, had by partners and children homeless. and publicity evening escalated into a riot over the treatment Before their transportation from immigration fa- Jess Lenehan Iof hundreds of men there by Home Affairs Minister cilities and prisons on the Australian mainland, some Peter Dutton and his Australian Border Force. Four of these men could receive visits from loved ones. Now What is days later, facing down reinforced numbers of masked, they can barely, if at all, get internet access to speak to armed Serco security thugs and Australian Federal them. -

Commonwealth Responsibility and Cold War Solidarity Australia in Asia, 1944–74

COMMONWEALTH RESPONSIBILITY AND COLD WAR SOLIDARITY AUSTRALIA IN ASIA, 1944–74 COMMONWEALTH RESPONSIBILITY AND COLD WAR SOLIDARITY AUSTRALIA IN ASIA, 1944–74 DAN HALVORSON Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463236 ISBN (online): 9781760463243 WorldCat (print): 1126581099 WorldCat (online): 1126581312 DOI: 10.22459/CRCWS.2019 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A1775, RGM107. This edition © 2019 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Abbreviations . ix 1 . Introduction . 1 2 . Region and regionalism in the immediate postwar period . 13 3 . Decolonisation and Commonwealth responsibility . 43 4 . The Cold War and non‑communist solidarity in East Asia . 71 5 . The winds of change . 103 6 . Outside the margins . 131 7 . Conclusion . 159 References . 167 Index . 185 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Cathy Moloney, Anja Mustafic, Jennifer Roberts and Lucy West for research assistance on this project. Thanks also to my colleagues Michael Heazle, Andrew O’Neil, Wes Widmaier, Ian Hall, Jason Sharman and Lucy West for reading and commenting on parts of the work. Additionally, I would like to express my gratitude to participants at the 15th International Conference of Australian Studies in China, held at Peking University, Beijing, 8–10 July 2016, and participants at the Seventh Annual Australia–Japan Dialogue, hosted by the Griffith Asia Institute and Japan Institute for International Affairs, held in Brisbane, 9 November 2017, for useful comments on earlier papers contributing to the manuscript. -

Debating Power and Revolution in Anarchism, Black Flame and Historical Marxism 1

Detailed reply to International Socialism: debating power and revolution in anarchism, Black Flame and 1 historical Marxism 7 April 2011 Source: http://lucienvanderwalt.blogspot.com/2011/02/anarchism-black-flame-marxism-and- ist.html Lucien van der Walt, Sociology, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, [email protected] **This paper substantially expands arguments I published as “Counterpower, Participatory Democracy, Revolutionary Defence: debating Black Flame, revolutionary anarchism and historical Marxism,” International Socialism: a quarterly journal of socialist theory, no. 130, pp. 193-207. http://www.isj.org.uk/index.php4?id=729&issue=130 The growth of a significant anarchist and syndicalist2 presence in unions, in the larger anti-capitalist milieu, and in semi-industrial countries, has increasingly drawn the attention of the Marxist press. International Socialism carried several interesting pieces on the subject in 2010: Paul Blackledge’s “Marxism and Anarchism” (issue 125), Ian Birchall’s “Another Side of Anarchism” (issue 127), and Leo Zeilig’s review of Michael Schmidt and my book Black Flame: the revolutionary class politics of anarchism and syndicalism (also issue 127).3 In Black Flame, besides 1 I would like to thank Shawn Hattingh, Ian Bekker, Iain McKay and Wayne Price for feedback on an earlier draft. 2 I use the term “syndicalist” in its correct (as opposed to its pejorative) sense to refer to the revolutionary trade unionism that seeks to combine daily struggles with a revolutionary project i.e., in which unions are to play a decisive role in the overthrow of capitalism and the state by organizing the seizure and self-management of the means of production. -

Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution

Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 2 2021 Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Chris Wright [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Chris (2021) "Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.9.1.009647 Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol9/iss1/2 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Abstract In the twenty-first century, it is time that Marxists updated the conception of socialist revolution they have inherited from Marx, Engels, and Lenin. Slogans about the “dictatorship of the proletariat” “smashing the capitalist state” and carrying out a social revolution from the commanding heights of a reconstituted state are completely obsolete. In this article I propose a reconceptualization that accomplishes several purposes: first, it explains the logical and empirical problems with Marx’s classical theory of revolution; second, it revises the classical theory to make it, for the first time, logically consistent with the premises of historical materialism; third, it provides a (Marxist) theoretical grounding for activism in the solidarity economy, and thus partially reconciles Marxism with anarchism; fourth, it accounts for the long-term failure of all attempts at socialist revolution so far. -

Solidarity: Reflections on an Emerging Concept in Bioethics

Solidarity: reflections on an emerging concept in bioethics Barbara Prainsack and Alena Buyx This report was commissioned by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics (NCoB) and was jointly funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and the Nuffield Foundation. The award was managed by the Economic and Social Research Council on behalf of the partner organisations, and some additional funding was made available by NCoB. For the duration of six months in 2011, Professor Barbara Prainsack was the NCoB Solidarity Fellow, working closely with fellow author Dr Alena Buyx, Assistant Director of NCoB. Disclaimer The report, whilst funded jointly by the AHRC, the Nuffield Foundation and NCoB, does not necessarily express the views and opinions of these organisations; all views expressed are those of the authors, Professor Barbara Prainsack and Dr Alena Buyx. The Nuffield Council on Bioethics is an independent body that examines and reports on ethical issues in biology and medicine. It is funded jointly by the Nuffield Foundation, the Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council, and has gained an international reputation for advising policy makers and stimulating debate in bioethics. www.nuffieldbioethics.org The Nuffield Foundation is an endowed charitable trust that aims to improve social wellbeing in the widest sense. It funds research and innovation in education and social policy and also works to build capacity in education, science and social science research. www.nuffieldfoundation.org Established in April 2005, the AHRC is a non-Departmental public body. It supports world-class research that furthers our understanding of human culture and creativity. www.ahrc.ac.uk © Barbara Prainsack and Alena Buyx ISBN: 978-1-904384-25-0 November 2011 Printed in the UK by ESP Colour Ltd. -

State of Affairs in Europe

State of affairs in Europe Workshop of Transform and Rosa Luxem- burg Foundation, July 7- 9 2016 Franz-Mehring-Platz 1, 10243 Berlin Documentation Cornelia Hildebrandt/Luci Wagner 30.07.2017 DOCUMENTATION: BERLIN SEMINAR 2016 2 Introduction This documentation is produced as a material outcome of the two days workshop that was organised by transform! Europe and the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation on 7 - July 2019 in Berlin under the title “State of affairs in Europe”. This European seminar aimed to bring together left-wing political actors and scholars to debate the possibilities of common perspectives and political action of the Left in Europe. When the preparation process of this seminar started the political landscape was of course different. Against the backdrop of blackmail of SYRIZA government in the nego- tiations with the institutions , further cuts to pensions and social benefits make the mass protests against these measures as against the implementation of the privatization, the continuation of neoliberal politics, the alarming soar of the far right in numerous coun- tries, but also the introduction of a progressive government in Portugal with the support of the left parties , the electoral success of Unidos Podemos in Spain etc., we believed that a new determination of the positioning of the Left is necessary. This is still our be- lief, despite the crucial and controversial developments that took place in Europe during 2017. In 2016 a respectable number of conferences, seminars and debates had been taken place (especially the foundation and conferences of DiEM-25, the conference ‘Building alliances to Fight Austerity and to Reclaim Democracy’ in Athens organized by trans- form!, the Party of the European Left and Nicos Poulantzas Institute, the “Plan B” - con- ferences and the strategy conference of the RLS). -

Practices of Refugee Support Between Humanitarian Help And

Larissa Fleischmann Contested Solidarity Culture and Social Practice Larissa Fleischmann, born in 1989, works as a Postdoctoral Researcher in Human Geography at the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. She received her PhD from the University of Konstanz, where she was a member of the Centre of Excellence »Cultural Foundations of Social Integration« and the Social and Cultu- ral Anthropology Research Group from 2014 to 2018. Larissa Fleischmann Contested Solidarity Practices of Refugee Support between Humanitarian Help and Political Activism Dissertation of the University of Konstanz Date of the oral examination: February 15, 2019 1st reviewer: Prof. Dr. Thomas G. Kirsch 2nd reviewer: PD Dr. Eva Youkhana 3rd reviewer: Prof. Dr. Judith Beyer This publication was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Re- search Foundation) - Project number 448887013. The author acknowledges the financial support of the Open Access Publication Fund of the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. The field research for this publication was funded by the Centre of Excellence “Cultural Foundations of Social Integration”, University of Konstanz. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 (BY- NC) license, which means that the text may be remixed, build upon and be distributed, provided credit is given to the author, but may not be used for commercial purposes. For details go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Permission to use the text for commercial purposes can be obtained by contacting rights@ transcript-publishing.com Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. -

Book 5 7, 8 and 9 March 2017

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL FIFTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Book 5 7, 8 and 9 March 2017 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable LINDA DESSAU, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC, QC The ministry (from 10 November 2016) Premier ........................................................ The Hon. D. M. Andrews, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Education and Minister for Emergency Services .................................................... The Hon. J. A. Merlino, MP Treasurer ...................................................... The Hon. T. H. Pallas, MP Minister for Public Transport and Minister for Major Projects .......... The Hon. J. Allan, MP Minister for Small Business, Innovation and Trade ................... The Hon. P. Dalidakis, MLC Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change, and Minister for Suburban Development ....................................... The Hon. L. D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Roads and Road Safety, and Minister for Ports ............ The Hon. L. A. Donnellan, MP Minister for Tourism and Major Events, Minister for Sport and Minister for Veterans ................................................. The Hon. J. H. Eren, MP Minister for Housing, Disability and Ageing, Minister for Mental Health, Minister for Equality and Minister for Creative Industries .......... The Hon. M. P. Foley, MP Minister for Health and Minister for Ambulance Services -

Alasdair Macintyre and Trotskyism

BlackledgeKnight-09_Layout 1 12/29/10 8:07 AM Page 152 9 Alasdair MacIntyre and Trotskyism Alasdair MacIntyre began his literary career in 1953 with Marxism: An Interpretation. According to his own account, in that book he attempted to be faithful to both his Christian and his Marxist beliefs (MacIntyre 1995d). Over the course of the 1960s he abandoned both (MacIntyre 2008k, 180). In 1971 he introduced a collection of his essays by rejecting these and, indeed, all other attempts to illuminate the human condition (MacIntyre 1971b, viii). Since then, MacIntyre has of course re-embraced Christianity, although that of the Catholic Church rather than the An - glicanism to which he originally adhered. It seems unlikely, at this stage, that he will undertake a similar reconciliation with Marxism. Nevertheless, as MacIntyre has frequently reminded his readers, most recently in the prologue to the third edition of After Virtue (2007), his rejection of Marxism as a whole does not entail a rejection of every insight that it has to o ffer. MacIntyre’s current audience tends to be un - interested in his Marxism and consequently remains in ignorance not only of his early Marxist work but also of the context in which it was written. MacIntyre not only wrote from a Marxist perspective but also belonged to a number of Marxist organisations, which, to di ffering de - grees, made political demands on their members from which intellec tu - 152 BlackledgeKnight-09_Layout 1 12/29/10 8:07 AM Page 153 Alasdair MacIntyre and Trotskyism 153 als were not excluded. Even the most insightful of MacIntyre’s admirers tend to treat the subject of these political a ffiliations as an occasion for mild amusement (Knight 1998, 2). -

From Cold War Solidarity to Transactional Engagement Reinterpreting Australia’S Relations with East Asia, 1950–1974

From Cold War Solidarity to Transactional Engagement Reinterpreting Australia’s Relations with East Asia, 1950–1974 ✣ Dan Halvorson Introduction The academic treatment of Australia’s engagement with Asia has concentrated almost entirely on Australian initiatives in the region and their perceived successes and failures. Historical work has focused on Australia’s postwar re- lationships with Britain and the United States and their ramifications for Canberra’s Cold War policy of “forward defence,” including involvement in the Vietnam War.1 This article offers a reinterpretation of the historical pat- tern of Australia’s Cold War engagement with East Asia based on new archival research conducted in Australia and the United Kingdom.2 The article marks an important shift in focus from previous work in seeking to emphasize the agency enjoyed by non-Communist East Asian states in their relationships with Australia during the Cold War. Australia’s outlook on the world tended to reflect global British Empire concerns until the Pacific War of 1941–1945 thanks to its Anglo-Celtic– derived society and geographic isolation on the fringes of an Asian-Pacific region dominated by European colonial powers. The fall of Britain’s Sin- gapore base to the advancing Japanese in February 1942 brought home to Australians the geographic reality that their country was firmly located in 1. See, for example, Gregory Pemberton, All the Way: Australia’s Road to Vietnam (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1987); Peter Edwards, with Gregory Pemberton, Crises and Commitments: The Politics and Diplomacy of Australia’s Involvement in Southeast Asian Conflicts 1948–1965 (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1992); Garry Woodard, Asian Alternatives: Australia’s Vietnam Decision and Lessons on Going to War (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2004); and Peter Edwards, Australia and the Vietnam War (Sydney: New South Publishing and Australian War Memorial, 2014). -

Transforming Charity Into Solidarity and Justice

Global Citizenship Education: Module 1 Transforming Charity into Solidarity and Justice SASKATCHEWAN COUNCIL FOR INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION WWW.EARTHBEAT.SK.CA T: 306-757-4669 SSASKACTCHEWANI CCOUNCIL FOR INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION We connect people and organizations to the information and ideas they need to take meaningful actions, and to be great global citizens. For more information visit our website, join us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter, or drop us a line. P: 306.757.4669 F: 306.757.3226 2138 McIntyre Street, Regina, SK S4P 2R7 [email protected] www.earthbeat.sk.ca SaskCIC @SaskCIC scicyouth Undertaken with the financial support of Global Affairs Canada SCIC would like to give a special thank you to the contributors in the development of Module 1: Transforming Charity into Solidarity and Justice. Contents TRANSFORMING CHARITY INTO SOLIDARITY AND JUSTICE . 3 WHAT’s in THE MODULE. .4 EDUCATION THEORY AND METHODOLOGY . 6 SOCIAL STUDIES CURRICULUM OUTCOMES AND INDICATORS. .7 LESSON #1 . .9 DEFINING CHARITY, JUSTICE, AND SOLIDARITY 1 Curriculum Outcomes What You’ll Need Before Activities • Introduction to Module 1 During Activities • Looking into Charity, Justice and Solidarity Fr After Activities • Checking for Understanding: Standing on the Spectrum Activity LESSON #2. .16 IDENTIFYING THE ROOT CAUSES OF SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS 2 Curriculum Outcomes What You’ll Need Before Activities • Entrance Slip • Babies in the River Parable During Activities • “Finding the Root Cause by Asking WHY” by Kailee Howorth Fr • Finding the Root Causes Activity • Looking into Solidarity After Activities • Checking for Understanding: Reviewing Student Answers to Finding Root Causes Activity MODULE 1: TRANSFORMING CHARITY INTO SOLIDARITY AND JUSTIce SASKATCHEWAN COUNCIL FOR INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION WWW.EARTHBEAT.SK.CA T: 306-757-4669 PAGE 1 LESSON #3.