New Synthetic Routes to Strained Cumulenes and Reactive Carbenes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14.8 Organic Synthesis Using Alkynes

14_BRCLoudon_pgs4-2.qxd 11/26/08 9:04 AM Page 666 666 CHAPTER 14 • THE CHEMISTRY OF ALKYNES The reaction of acetylenic anions with alkyl halides or sulfonates is important because it is another method of carbon–carbon bond formation. Let’s review the methods covered so far: 1. cyclopropane formation by the addition of carbenes to alkenes (Sec. 9.8) 2. reaction of Grignard reagents with ethylene oxide and lithium organocuprate reagents with epoxides (Sec. 11.4C) 3. reaction of acetylenic anions with alkyl halides or sulfonates (this section) PROBLEMS 14.18 Give the structures of the products in each of the following reactions. (a) ' _ CH3CC Na| CH3CH2 I 3 + L (b) ' _ butyl tosylate Ph C C Na| + L 3 H3O| (c) CH3C' C MgBr ethylene oxide (d) L '+ Br(CH2)5Br HC C_ Na|(excess) + 3 14.19 Explain why graduate student Choke Fumely, in attempting to synthesize 4,4-dimethyl-2- pentyne using the reaction of H3C C'C_ Na| with tert-butyl bromide, obtained none of the desired product. L 3 14.20 Propose a synthesis of 4,4-dimethyl-2-pentyne (the compound in Problem 14.19) from an alkyl halide and an alkyne. 14.21 Outline two different preparations of 2-pentyne that involve an alkyne and an alkyl halide. 14.22 Propose another pair of reactants that could be used to prepare 2-heptyne (the product in Eq. 14.28). 14.8 ORGANIC SYNTHESIS USING ALKYNES Let’s tie together what we’ve learned about alkyne reactions and organic synthesis. The solu- tion to Study Problem 14.2 requires all of the fundamental operations of organic synthesis: the formation of carbon–carbon bonds, the transformation of functional groups, and the establish- ment of stereochemistry (Sec. -

Organic Chemistry

Wisebridge Learning Systems Organic Chemistry Reaction Mechanisms Pocket-Book WLS www.wisebridgelearning.com © 2006 J S Wetzel LEARNING STRATEGIES CONTENTS ● The key to building intuition is to develop the habit ALKANES of asking how each particular mechanism reflects Thermal Cracking - Pyrolysis . 1 general principles. Look for the concepts behind Combustion . 1 the chemistry to make organic chemistry more co- Free Radical Halogenation. 2 herent and rewarding. ALKENES Electrophilic Addition of HX to Alkenes . 3 ● Acid Catalyzed Hydration of Alkenes . 4 Exothermic reactions tend to follow pathways Electrophilic Addition of Halogens to Alkenes . 5 where like charges can separate or where un- Halohydrin Formation . 6 like charges can come together. When reading Free Radical Addition of HX to Alkenes . 7 organic chemistry mechanisms, keep the elec- Catalytic Hydrogenation of Alkenes. 8 tronegativities of the elements and their valence Oxidation of Alkenes to Vicinal Diols. 9 electron configurations always in your mind. Try Oxidative Cleavage of Alkenes . 10 to nterpret electron movement in terms of energy Ozonolysis of Alkenes . 10 Allylic Halogenation . 11 to make the reactions easier to understand and Oxymercuration-Demercuration . 13 remember. Hydroboration of Alkenes . 14 ALKYNES ● For MCAT preparation, pay special attention to Electrophilic Addition of HX to Alkynes . 15 Hydration of Alkynes. 15 reactions where the product hinges on regio- Free Radical Addition of HX to Alkynes . 16 and stereo-selectivity and reactions involving Electrophilic Halogenation of Alkynes. 16 resonant intermediates, which are special favor- Hydroboration of Alkynes . 17 ites of the test-writers. Catalytic Hydrogenation of Alkynes. 17 Reduction of Alkynes with Alkali Metal/Ammonia . 18 Formation and Use of Acetylide Anion Nucleophiles . -

Chemical Kinetics HW1 (Kahn, 2010)

Chemical Kinetics HW1 (Kahn, 2010) Question 1. (6 pts) A reaction with stoichiometry A = P + 2Q was studied by monitoring the concentration of the reactant A as a function of time for eighteen minutes. The concentration determination method had a maximum error of 6 M. The following concentration profile was observed: Time (min) Conc (mM) 1 0.9850 2 0.8571 3 0.7482 4 0.6549 5 0.5885 6 0.5183 7 0.4667 8 0.4281 9 0.3864 10 0.3557 11 0.3259 12 0.3037 13 0.2706 14 0.2486 15 0.2355 16 0.2188 17 0.2111 18 0.1930 Determine the reaction order and calculate the rate constant for decomposition of A. What can be said about the mechanism or molecularity of this reaction? Question 2. (4 pts) Solve problem 2 on pg 31 in your textbook (House) using both linear and non-linear regression. Provide standard errors for the rate constant and half-life based on linear and non-linear fits. Below is the data set for your convenience: dataA = {{0, 0.5}, {10, 0.443}, {20,0.395}, {30,0.348}, {40,0.310}, {50,0.274}, {60,0.24}, {70,0.212}, {80,0.190}, {90,0.171}, {100,0.164}} Question 3. (3 pts) Solve problem 3 on pg 32 in your textbook (House). Question 4. (7 pts) The authors of the paper “Microsecond Folding of the Cold Shock Protein Measured by a Pressure-Jump Technique” suggest that the activated state of folding of CspB follows Hammond- type behavior. -

S1 Supporting Information Copper-Catalyzed

Supporting Information Copper-Catalyzed Semihydrogenation of Internal Alkynes with Molecular Hydrogen Takamichi Wakamatsu, Kazunori Nagao, Hirohisa Ohmiya*, and Masaya Sawamura* Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Hokkaido University, Sapporo 060-0810, Japan Table of Contents Instrumentation and Chemicals S1 Characterization Data for Alkynes S1–S2 Procedure for the Copper-Catalyzed Semihydrogenation of Alkynes S2 Characterization Data for Alkenes S3–S5 References S5 NMR Spectra S6–S31 Instrumentation and Chemicals NMR spectra were recorded on a JEOL ECX-400, operating at 400 MHz for 1H NMR and 100.5 13 1 13 MHz for C NMR. Chemical shift values for H and C are referenced to Me4Si and the residual solvent resonances, respectively. Mass spectra were obtained with Thermo Fisher Scientific Exactive, JEOL JMS-T100LP or JEOL JMS-700TZ at the Instrumental Analysis Division, Equipment Management Center, Creative Research Institution, Hokkaido University. TLC analyses were performed on commercial glass plates bearing 0.25-mm layer of Merck Silica gel 60F254. Silica gel (Kanto Chemical Co., Silica gel 60 N, spherical, neutral) was used for column chromatography. Materials were obtained from commercial suppliers or prepared according to standard procedure unless otherwise noted. CuCl was purchased from Aldrich Chemical Co., stored under nitrogen, and used as it is. NatOBu, octane and 6-dodecyne 1a were purchased from TCI Chemical Co., stored under nitrogen, and used as it is. Diphenylacetylene 1j was purchased from Wako Chemical Co., stored under nitrogen, and used as it is. 1,4-Dioxane was purchased from Kanto Chemical Co., distilled from sodium/benzophenone and stored over 4Å molecular sieves under nitrogen. -

The Synthesis of a Polydiacetylene to Create a Novel Sensory Material

SELDE, KRISTEN A., M.S. The Synthesis of a Polydiacetylene to Create a Novel Sensory Material. (2007) Directed by Dr. Darrell Spells. 47pp. Sensory materials that respond to chemical and mechanical stimuli are under development in many laboratories. There are many significant uses of polydiacetylene compounds as sensory material. They have been applied to drug delivery, drug design, biomolecule development, cosmetics, and national security. In this study, experiments were carried out toward the development of a novel sensory material based on the established synthetic research on polydiacetylene compounds. Synthetic routes toward sensory materials with different head groups, different carbon chains lengths, and the incorporation of molecular imprints were explored. Diacetylene moieties, which can be used for polymer vesicle formation, were prepared by two main routes. In one route, 1-iodo-1-octyne and 1-iodo-1-dodecyne were prepared as starting materials for the synthesis of two diacetylene compounds (Diacetylene I and Diacetylene II). In the other route, a mesityl alkyne was used to prepare 5-iodo-1-pentyne, which was then used to prepare a triethylamino alkyne. This in turn was used to synthesize a diacetylene (Diacetylene III). Although each diacetylene product was formed, purification by column chromatography was found to be difficult. Experiments in vesicle formation, with and without molecular imprints, were also carried out using commercially available diacetylenes . THE SYNTHESIS OF A POLYDIACETYLENE TO CREATE A NOVEL SENSORY -

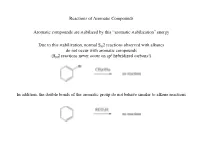

2 Reactions Observed with Alkanes Do Not Occur with Aromatic Compounds 2 (SN2 Reactions Never Occur on Sp Hybridized Carbons!)

Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Aromatic compounds are stabilized by this “aromatic stabilization” energy Due to this stabilization, normal SN2 reactions observed with alkanes do not occur with aromatic compounds 2 (SN2 reactions never occur on sp hybridized carbons!) In addition, the double bonds of the aromatic group do not behave similar to alkene reactions Aromatic Substitution While aromatic compounds do not react through addition reactions seen earlier Br Br Br2 Br2 FeBr3 Br With an appropriate catalyst, benzene will react with bromine The product is a substitution, not an addition (the bromine has substituted for a hydrogen) The product is still aromatic Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution Aromatic compounds react through a unique substitution type reaction Initially an electrophile reacts with the aromatic compound to generate an arenium ion (also called sigma complex) The arenium ion has lost aromatic stabilization (one of the carbons of the ring no longer has a conjugated p orbital) Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution In a second step, the arenium ion loses a proton to regenerate the aromatic stabilization The product is thus a substitution (the electrophile has substituted for a hydrogen) and is called an Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution Energy Profile Transition states Transition states Intermediate Potential E energy H Starting material Products E Reaction Coordinate The rate-limiting step is therefore the formation of the arenium ion The properties of this arenium ion therefore control electrophilic aromatic substitutions (just like any reaction consider the stability of the intermediate formed in the rate limiting step) 1) The rate will be faster for anything that stabilizes the arenium ion 2) The regiochemistry will be controlled by the stability of the arenium ion The properties of the arenium ion will predict the outcome of electrophilic aromatic substitution chemistry Bromination To brominate an aromatic ring need to generate an electrophilic source of bromine In practice typically add a Lewis acid (e.g. -

Development of a Solid-Supported Glaser-Hay Reaction and Utilization in Conjunction with Unnatural Amino Acids

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2015 Development of a Solid-Supported Glaser-Hay Reaction and Utilization in Conjunction with Unnatural Amino Acids Jessica S. Lampkowski College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Organic Chemistry Commons Recommended Citation Lampkowski, Jessica S., "Development of a Solid-Supported Glaser-Hay Reaction and Utilization in Conjunction with Unnatural Amino Acids" (2015). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626985. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-r9jh-9635 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Development of a Solid-Supported Glaser-Hay Reaction and Utilization in Conjunction with Unnatural Amino Acids Jessica Susan Lampkowski Ida, Michigan B.S. Chemistry, Siena Heights University, 2013 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Science Chemistry Department The College of William and Mary May, 2015 COMPLIANCE PAGE Research approved by Institutional Biosafety Committee Protocol number: BC-2012-09-13-8113-dyoung01 Date(s) of approval: This protocol will expire on 2015-11-02 APPROVAL PAGE This -

Strain-Promoted 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition of Cycloalkynes and Organic Azides

Top Curr Chem (Z) (2016) 374:16 DOI 10.1007/s41061-016-0016-4 REVIEW Strain-Promoted 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition of Cycloalkynes and Organic Azides 1 1 Jan Dommerholt • Floris P. J. T. Rutjes • Floris L. van Delft2 Received: 24 November 2015 / Accepted: 17 February 2016 / Published online: 22 March 2016 Ó The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract A nearly forgotten reaction discovered more than 60 years ago—the cycloaddition of a cyclic alkyne and an organic azide, leading to an aromatic triazole—enjoys a remarkable popularity. Originally discovered out of pure chemical curiosity, and dusted off early this century as an efficient and clean bio- conjugation tool, the usefulness of cyclooctyne–azide cycloaddition is now adopted in a wide range of fields of chemical science and beyond. Its ease of operation, broad solvent compatibility, 100 % atom efficiency, and the high stability of the resulting triazole product, just to name a few aspects, have catapulted this so-called strain-promoted azide–alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) right into the top-shelf of the toolbox of chemical biologists, material scientists, biotechnologists, medicinal chemists, and more. In this chapter, a brief historic overview of cycloalkynes is provided first, along with the main synthetic strategies to prepare cycloalkynes and their chemical reactivities. Core aspects of the strain-promoted reaction of cycloalkynes with azides are covered, as well as tools to achieve further reaction acceleration by means of modulation of cycloalkyne structure, nature of azide, and choice of solvent. Keywords Strain-promoted cycloaddition Á Cyclooctyne Á BCN Á DIBAC Á Azide This article is part of the Topical Collection ‘‘Cycloadditions in Bioorthogonal Chemistry’’; edited by Milan Vrabel, Thomas Carell & Floris P. -

A. Discovery of Novel Reactivity Under the Sonogashira Reaction Conditions B. Synthesis of Functionalized Bodipys and BODIPY-Sug

A. Discovery of novel reactivity under the Sonogashira reaction conditions B. Synthesis of functionalized BODIPYs and BODIPY-sugar conjugates Ravi Shekar Yalagala, M.Phil Department of Chemistry Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Mathematics and Science, Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario © 2016 ABSTRACT A. During our attempts to synthesize substituted enediynes, coupling reactions between terminal alkynes and 1,2-cis-dihaloalkenes under the Sonogashira reaction conditions failed to give the corresponding substituted enediynes. Under these conditions, terminal alkynes underwent self-trimerization or tetramerization. In an alternative approach to access substituted enediynes, treatment of alkynes with trisubstituted (Z)- bromoalkenyl-pinacolboronates under Sonogashira coupling conditions was found to give 1,2,4,6-tetrasubstituted benzenes instead of Sonogashira coupled product. The reaction conditions and substrate scopes for these two new reactions were investigated. B. BODIPY core was functionalized with various functional groups such as nitromethyl, nitro, hydroxymethyl, carboxaldehyde by treating 4,4-difluoro-1,3,5,7,8- pentamethyl-2,6-diethyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene with copper (II) nitrate trihydrate under different conditions. Further, BODIPY derivatives with alkyne and azido functional groups were synthesized and conjugated to various glycosides by the Click reaction under the microwave conditions. One of the BODIPY–glycan conjugate was found to form liposome upon rehydration. The photochemical properties of BODIPY in these liposomes were characterized by fluorescent confocal microscopy. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am extremely grateful to a number of people. Without their help, this document would have never been completed. First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor and mentor Professor Tony Yan for his guidance and supervision to make the thesis possible. -

Reaction Mechanism Lecture 3 : Nucleophilic And

Module 10 : Reaction mechanism Lecture 3 : Nucleophilic and Electrophilic Addition and Abstraction Objectives In this lecture you will learn the following Ligand activation by metal that leads to a direct external attack at the ligand. Nucleophilic addition and nucleophilic abstraction reactions. Electrophilic addition and electrophilic abstraction reactions. The nucleophilic and electrophilic substitution and abstraction reactions can be viewed as ways of activation of substrates to allow an external reagent to directly attack the metal activated ligand without requiring prior binding of the external reagent to the metal. The attacking reagent may be a nucleophile or an electrophile. The nucleophilic attack of the external reagent is favored if the LnM fragment is a poor π−base and a good σ−acid i.e., when the complex is cationic and/or when the other metal bound ligands are electron withdrawing such that the ligand getting activated gets depleted of electron density and can undergo an external attack by a nucleophile Nu−, like LiMe or OH−. The attack of the nucleophiles may result in the formation of a bond between the nucleophiles and the activated unsaturated substrate, in which case it is called nucleophilic addition, or may result in an abstraction of a part or the whole of the activated ligand, in which case it is called the nucleophilic abstraction. The nucleophilic addition and the abstraction reactions are discussed below. Nucleophilic addition An example of a nucleophilic addition reaction is shown below. Carbon monoxide (CO) as a ligand can undergo nucleophilic attack when bound to a metal center of poor π−basicity, as the carbon center of the CO ligand is electron deficient owing to the ligand to metal σ−donation not being fully compensated by the metal to ligand π−back donation. -

Alkenes Electrophilic Addition

Alkenes Electrophilic Addition 1 Alkene Structures chemistry of C C double bond σ C–C BDE ~ 80 kcal/mol π C=C BDE ~ 65 kcal/mol • The p-bond is weaker than the sigma-bond • The, electrons in the p-bond are higher in energy than those in the s-bond • The electrons in the p-bond are more chemically reactive than those in the s-bond Energy σ∗ M.O. π∗ M.O. p p ~ 65 kcal/mol 2 π bond alkene uses the electrons in sp2 sp THIS orbital π M.O. atomic atomic when acting as a orbitals orbitals ~ 81 kcal/mol LEWIS BASE carbon 1 carbon 2 σ bond σ M.O. molecular orbitals • The alkene uses the electrons in the p-bond when it reacts as a Lewis Base/nucleophile How do you break a p-bond? H H H H H D C C rotate C C rotate C C D D D D H 90° D cis-isomer trans-isomer zero overlap of p orbitals: π bond broken! Energy H H H D D D D H ~ 63 kcal/mol 0° 90° 180° • Rotation around a sigma-bond hardly changes the energy of the electrons in the bond because rotation does not significantly change the overlap of the atomic orbitals that make the bonding M.O. • Rotation around a p-bond, however, changes the overlap of the p AOs that are used to make the bonding M.O., at 90° there is no overlap of the p A.O.s, the p-bond is broken Alkenes : page 1 Distinguishing isomers trans- cis- • By now we are very familiar with cis- and trans-stereoisomers (diastereomers) • But what about, the following two structures, they can NOT be assigned as cis- or trans-, yet they are definitely stereoisomers (diastereomers), the directions in which their atoms point in space are different cis- / trans- Br Br We Need a different system to distinguish stereoisomers for C=C double bonds: Use Z/E notation. -

Subject Index

455 Subject Index Aminohydroxylation, 364 a-Aminoketone, 281 4-Aminophenol, 18 A Aminothiophene, 158 Abnormal Claisen rearrangement, 1 a-Aminothiophenols, 184 Acrolein, 378 Ammonium ylide, 383 2-(Acylamino)-toluenes, 245 Angeli-Rimini hydroxamic acid Acylation, 100, 145, 200 synthesis, 9 Acyl azides, 98 ~-Anomer, 225 Acylium ion, 145, 149, 175, 177 Anomeric center, 211 a-Acyloxycarboxamides, 298 Anomeric effect, 135 a-Acyloxyketones, 17 ANRORC mechanism, 10 a-Acyloxythioethers, 327 Anthracenes, 51 Acyl transfer, 17, 42, 228, 298, 305, Anti-Markovnikov addition, 219 327,345 Amdt-Eistert homologation, 11 AIBN, 22, 23, 415 Aryl-acetylene, 66 Alder ene reaction, 2 Arylation, 253 Alder's endo rule, Ill 0-Aryliminoethers, 67 Aldol condensation, 3, 14, 26, 34, 2-Arylindoles, 38 69, 130, 147, 172, 305, Aryl migration, 31 340,396,412 Autoxidation, 69, 115, 118 Aldosylamine, 8 Auwers reaction, 13 Alkyl migration, 16, 132, 315, 443 Axial, 347 Alkylation, 144, 145 Azalactone, I 00 N-Aikylation, 162 Azides, 125, 330 Alkylidene carbene, 151 Azirine, 6, 7, 281 Allan-Robinson reaction, 4, 228 Azulene, 310 Allene, 119 1t-Allyl complex, 414 B Allylation, 213, 414 Baeyer-Drewson Allylstannane, 213 indigo synthesis, 14 Allylsilanes, 349 Baeyer-Villiger oxidation, 16, 53 Alper carbonylation, 6 Baker-Venkataraman Alpine-borane®, 262 rearrangement, 17 Aluminum phenolate, 149 Balz-Schiemann reaction, 354 Amadori rearrangement, 8 Bamberger rearrangement, 18 Amide acetal, 74 Bamford-Stevens reaction, 19 Amides, 28, 67,276,339, 356 Bargellini reaction, 20 Amidine,