Covid-19 and the Pandemic of Fear: Some Reflections from the Jaina Perspective*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JMC FINAL REPORT 2015-16 FINAL NEW 1254.Xlsx

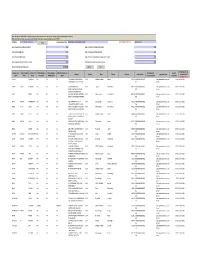

-! JALGAOI{ MUNICIPAL CORPORATION DIST: . JALGAON FINANCIAL STATE,MENTS FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR 04l-4t201s To 31103t2016 PREPARED BY :- e - S. S. LODHA & ASSOCIATES - CHARTERED ACCOUNTAI{TS 16117, FIRST FLOOR, OLD B.J. MARKET, JALGAON- 425OOI. - : f, s I ^ru{ts-- 'L\)y\l\t I -- : t 1' JALGAON CITY MUNICIPAL CORPORATION, JALGAON Balance Sheet As on 3110312016 lt Accou nl Schedule 2015-2016 2014-2015 1- Liabilities t_ Code No Amount ( Rs ) Amount ( Rs ) I I 3100 Municipal Fund & Reserryes B-1 803811883.58 529884448.18 : 3200 Grants Contribution for Speci{ic Purpose B.-2 738174958.60 49364s47s.60 t Loans B-3 1792639899.00 1861948199.00 t 3300 Secured & Unsecured I Current Liabilities & Provisions 3400 Interest on Loan B-4 t994025627.00 2t921 10842.00 I 3500 Employers Liability B-5 287709817.78 305720483.45 3600 Suppliers, Contractors & Other Liabilities B-6 342t87646.53 362656242.03 i 3700 Liability to citizens B-7 17s000.00 512543.00 - 3800 Amount Payable to Government B-8 9067420.50 13501271.00 3900 Others liabilites B-9 62456298.00 40257678.00 Total Current Liabilities & Provisions 2695621809.81 29147s9059.48 -\< Grand Total of Liabilities 6030248550.99 5800237182.26 -Li{ Account Schedule f- Assets Code No t -t! Fixed Assets : - 4100 Fixed & Movable Assets B-10 s949806750.80 5935506878.80 t 4200 Less :- Accumulated Depreciation B-11 (1880197740.16) (18791s8193.i6) 4300 Capital Work in Progress 0.00 0.00 L.-I Total F'ixed Assets 4069609010.64 4056348685.64 l' b--I 4400 Investments B-12 245133855.73 219815705.73 i \ Current Assets : - 4500 -

Heritage of Mysore Division

HERITAGE OF MYSORE DIVISION - Mysore, Mandya, Hassan, Chickmagalur, Kodagu, Dakshina Kannada, Udupi and Chamarajanagar Districts. Prepared by: Dr. J.V.Gayathri, Deputy Director, Arcaheology, Museums and Heritage Department, Palace Complex, Mysore 570 001. Phone:0821-2424671. The rule of Kadambas, the Chalukyas, Gangas, Rashtrakutas, Hoysalas, Vijayanagar rulers, the Bahamanis of Gulbarga and Bidar, Adilshahis of Bijapur, Mysore Wodeyars, the Keladi rulers, Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan and the rule of British Commissioners have left behind Forts, Magnificient Palaces, Temples, Mosques, Churches and beautiful works of art and architecture in Karnataka. The fauna and flora, the National parks, the animal and bird sanctuaries provide a sight of wild animals like elephants, tigers, bisons, deers, black bucks, peacocks and many species in their natural habitat. A rich variety of flora like: aromatic sandalwood, pipal and banyan trees are abundantly available in the State. The river Cauvery, Tunga, Krishna, Kapila – enrich the soil of the land and contribute to the State’s agricultural prosperity. The water falls created by the rivers are a feast to the eyes of the outlookers. Historical bakground: Karnataka is a land with rich historical past. It has many pre-historic sites and most of them are in the river valleys. The pre-historic culture of Karnataka is quite distinct from the pre- historic culture of North India, which may be compared with that existed in Africa. 1 Parts of Karnataka were subject to the rule of the Nandas, Mauryas and the Shatavahanas; Chandragupta Maurya (either Chandragupta I or Sannati Chandragupta Asoka’s grandson) is believed to have visited Sravanabelagola and spent his last years in this place. -

Date of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 03-AUG-2017

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L51491WB1983PLC035793 Prefill Company/Bank Name KANCO TEA & INDUSTRIES LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 03-AUG-2017 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 0.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 277426.50 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) AABHA AGRAWAL NA NA NA 11 GULMARG COMPLEX NEAR INDIA Madhya Pradesh Indore 452001 P0000000000000002 Sales proceed for fractional 37.96 22-JUN-2020 SAPNA SANGITA CINEMA INDORE 072 shares AAPUJI SUJAJI KUMBHAR NA NA NA FAKIRDAS NEW CAHLI INDIA Gujarat Ahmedabad 380024 P0000000000000000 Sales proceed for fractional 37.96 22-JUN-2020 BHBHIDBHANJAN HANUMAN 943 shares NIKOL ROAD AHMEDABAD AARTI SHETH NA NA NA 403 ASHA NIKETAN 45 BAPTISTA INDIA Maharashtra Mumbai City 400056 P0000000000000002 Sales proceed for fractional -

Essence of Bhagavan Dattaatreya- Magnificence of Tripurambimka

ESSENCE OF BHAGAVAN DATTAATREYA- MAGNIFICENCE OF TRIPURAMBIMKA Translated and interpreted by V.D.N.Rao 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu, Matsya, Varaha, Kurma, Vamana, Narada, Padma; Shiva, Linga, Skanda, Markandeya, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma, Brahma Vaivarta, Agni, Bhavishya, Nilamata; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa- Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama:a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri;b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata;c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers -Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu - Dharma Bindu - Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana-Essence of Paraashara Smriti- Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima- Essence of Ashtaadasha Upanishads: Brihadarankya, Katha, Taittiriya/ Taittiriya Aranyaka , Isha, Svetashvatara, Maha Narayana and Maitreyi, Chhadogya and Kena, Atreya and Kausheetaki, Mundaka, Maandukya, Prashna, Jaabaala and Kaivalya. Also „Upanishad Saaraamsa‟ - Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata- Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti -Essence of Brahma Sutras- Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Essence of Knowledge of Numbers for students-Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and AusteritiesEssence of Manu Smriti- Quintessence of Manu Smriti- Essence of Paramartha Saara; Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskra; Essence of Pratyaksha Chandra; Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak -

„Rediscovering Jain Tradition in Wayanad‟

„REDISCOVERING JAIN TRADITION IN WAYANAD‟ MINOR RESEARCH PROJECT IN HISTORY SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION 2014-15 SASI C T (PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR) DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY GOVT COLLEGE, KALPETTA WAYANAD, KERALA - 673121 CONTENT Page No. 1. Declaration 2. Certificate 3. Acknowledgement 4. Preface, Objectives, Methodology 5. Literature Review i-iv 6. Chapter 1 1-5 7. Chapter 2 6-9 8. Chapter 3 10-12 9. Chapter 4 13-22 10 Chapter 5 23-27 11 Chapter 6 28-31 12 Chapter 7 32-34 13 Appendices 35-37 14 Table 38-41 15 Images 42-56 16 Select Bibliography 57-59 (A video graphic representation on the Jain temples is attached separately in a DVD) DECLARATION I, Sasi C.T, Principal Investigator, (Assistant Professor, Department Of History, Govt College, Kalpetta, Wayanad, Kerala) do here by declare that, this is a bona fide work by me, and that it was undertaken as a Minor Research Project funded by the University Grants Commission during the period 2014-15. Kalpetta 22/9/2015 SASI C T CERTIFICATE Govt College Kalpetta, Wayanad Kerala This is to certify that this Minor Research Project entitled „REDISCOVERING JAIN TRADITION IN WAYANAD‟, submitted to the University Grants Commission is a Minor research work carried out by Sasi C T, Assistant Professor, Department of History, Govt.College, Kalpetta. No part of this work has been submitted before. Kalpetta 22/9/2015 Principal ACKNOWLEDGEMENT For doing the Minor Research Project on „Rediscovering Jain traditions in Wayanad‟ I am owed much to the assistance of distinguished personalities and institutions. I am expressing my sincere thanks to the Librarians of different Libraries. -

Brigade Enterprises Limited Unpaid/Unclaimed Equity Dividend List As on 31-08-2016 for the Year 2013-2014

Brigade Enterprises Limited Unpaid/Unclaimed equity dividend list as on 31-08-2016 for the year 2013-2014 Slno Name of the Holder Address of the Holder District Folio/Clientid Amount IEPF Date 1 S H SIDDAPPA Bharath Betelnut Company APMC Yard Shimoga SHIMOGA IN30009511126056 2000.00 11-SEP-2021 2 YUGAL KISHORE PINGUA PNB LARI ARWAL BIHAR ARWAL 1201320000233591 82.00 11-SEP-2021 3 M SUBRAHMANYAM B-3, DURGA COMPLEX SOMUVARI STREET KOTHAPET GUNTUR ANDHRA PRADESH GUNTUR 1201350000035214 64.00 11-SEP-2021 PARAS MAL JAIN NAME KUMAR OARASMAL 670 , VIDHYA DHAR KA RASTA TRIPOLIA BAZAR JAIPUR RAJASTHAN 4 JAIPUR 1201770100160648 20.00 11-SEP-2021 5 MANOJ KUMAR PAL H. NO. 47 NEAR OLD MIDDLE SCHOOL KARIM BUX COLONY CHHOLA NAKA BHOPAL MP BHOPAL 1203160000098926 90.00 11-SEP-2021 6 LAXMANDAS MANWANI H.NO-13, TALLAIYA CHOWKI BHOPAL BHOPAL M.P BHOPAL 1203160000118027 32.00 11-SEP-2021 7 MANPUNEET SINGH 924 DR.MUKERJEE NAGAR DELHI NEW DELHI IN30020610257703 100.00 11-SEP-2021 8 ASHA JAIN H NO 1436 OUTRAM LINE GTB NAGAR DELHI NEW DELHI IN30114310941400 114.00 11-SEP-2021 9 DEEPANKAR KAWATRA H.NO- 63 RAJA GARDEN NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 1202600000026722 40.00 11-SEP-2021 10 SAROJ GOLCHHA HOUSE NO. 9-T SECTOR -7 DDA FLATS JASSOLA DELHI NEW DELHI 1201910101831661 32.00 11-SEP-2021 11 MOHD MANSOOR AHMAD 99/29 2ND FLOOR ZAKIR NAGAR OKHLA NR POST OFFICE NEW DELHI NEW DELHI IN30051317760387 2.00 11-SEP-2021 12 PUNAM CHAND GUPTA C 70 SHIVAJI PARK NEW DELHI NEW DELHI IN30177411272041 114.00 11-SEP-2021 13 SANTOSH DHINGRA ROAD NO 3 HOUSE NO 10 EAST PUNJABI BAGH NEW DELHI DELHI NEW DELHI 1201910102077747 58.00 11-SEP-2021 14 BHAGWANT SINGH J-206 RAJOURI GARDEN NEW DELHI NEW DELHI IN30020610093074 114.00 11-SEP-2021 15 HARMINDER KAUR J - 206 RAJOURI GARDEN NEW DELHI NEW DELHI IN30020610338224 114.00 11-SEP-2021 16 SWATI JAIN 2525 / 9, STREET NO. -

The Uses of Jain Sati Name Lists

8 THINKING COLLECTIVELY ABOUT JAIN SATIS The uses of Jain sati name lists M. Whitney Kelting Jains venerate virtuous women (satis) who are virtuous and who, through their virtue, protect, promote, or merely uphold Jain values and the Jain religion. Jains narrate the lives of satis both individually and in the context of Jain Universal Histories (such as the Fvetambar Trisastifalakapurusacaritra of Hemacandra and the Digambar Adipuraja of Jinasena) and some of these satis are named in early Jain texts like the Fvetambar Kalpa Sutra. Fvetambar Jains also list satis (often sixteen of the following names: Brahmi, Sundari, Candanbala, Rajimati, Draupadi, Kaufalya, Mrgavati, Sulasa, Sita, Subhadra, Fiva, Kunti, Filavati, Damayanti, Puspacula, Prabhavati, and Padmavati) who stand in for the greater totality of satis. They also have more inclusive lists which extend the title sati to an unbounded number of women. Sati lists, through their fluidity and their inclusivity, serve as representatives of the totality of women’s virtue and as such are efficacious primarily by creating auspiciousness but also by reducing karma. While satis are revered in all Jain sects, this discussion is centered on the ways that Fvetambar Murtipujak Tapa Gacch Jains have constructed the idea of collectivities of satis.1 At present there are five gacchs (mendicant lineages) of Fvetambar Murtipujak Jain mendicants: Tapa, Añcal, Khartar, Paican, and Tristuti. Between 85 and 90 percent of the Fvetambar Murtipujak mendicants belong to the Tapa Gacch, which was formed in -

Select Bibliography

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources Àcàrà«ga-sùtra, edited as The Àyàraága Sutta of the •vetàmbara Jains by H. Jacobi. London: Pali Text Society, 1882. Àdi Purà»a of Jinasena. Pannalal Jain, trans. Varanasi: Bharatiya Jnanpith Prakashan, 1963–1965. A«gavijjà. Muni Shri Punyavijayaji, ed. Varanasi: Prakrit Text Society Series, 1957. A«guttara Nikàya, edited as The Book of Gradual Sayings by F. L. Woodward and E. M. Hare. Pali Text Society Translation Series, nos. 22, 24–27; 5 vols. London: Pali Text Society, 1932–36. Buddhacarita of A≤vaghoßa, translated as A≤vaghoßa’s Buddhacarita or Acts of the Buddha by E. H. Johnston. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1984. The Gàtakamàlà or Garland of Birth-Stories by Aryasùra. J. S. Speyer, trans. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1990. The Geography of Strabo. Horace Leonard Jones, trans. Loeb Classical Library Series. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 1949. Gilgit Manuscripts. Nalinaksha Dutt, ed. Srinagar, Kashmir: J. C. Sarkhel, at the Calcutta Press, 1939. Jaiminìya Upanißad Bràhma»a. H. W. Bodewitz, trans. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1973. Jaina Sùtras. Trans. H. Jacobi. Sacred Books of the East, XLV. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1968. The Jàtaka or Stories of the Buddha’s Former Births. E. B. Cowell, ed. 6 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1895–1905. The Mahàbhàrata. J. A. B. van Buitenen, ed. and trans. 3 vols. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973. M‰cchaka†ikà of •ùdraka, in Two Plays of Ancient India. J. A. B. van Buitenen, trans. New York: Columbia University Press, 1968. Natural History of Pliny. H. Rackham, trans. Loeb Classical Library Series. -

Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism.Pdf

Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism Handbook of Oriental Studies Section Two South Asia Edited by Johannes Bronkhorst VOLUME 24 Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism By Johannes Bronkhorst LEIDEN • BOSTON 2011 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bronkhorst, Johannes, 1946– Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism / By Johannes Bronkhorst. pages cm. — (Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 2, South Asia, ISSN 0169-9377 ; v. 24) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-20140-8 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Buddhism—Relations— Brahmanism. 2. Brahmanism—Relations—Buddhism. 3. Buddhism—India—History. I. Title. BQ4610.B7B76 2011 294.5’31—dc22 2010052746 ISSN 0169-9377 ISBN 978 90 04 20140 8 Copyright 2011 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. CONTENTS Preface ................................................................................................ -

List of Members

Karnataka Jain Association (R.) No. 81, K.R. Road, Shankarapuram, Bangalore - 560 004 Revised Members (Voters) list as on 01.03.2019 Sl.No. Name M.S. No. Place Taluk District 1 Abha Jain 2277 Bangalore Bangalore Bangalore 2 Abhay Kumar Jayakumar Patil 6814 Konnur Gokak Belagavi 591 231 3 Abhay Kumar M. Sooji 6677 Hubli Hubli Hubli 580 023 4 Abhay Kumar Managavi 4949 Rajajinagar Bangalore Bangalore 560 010 5 Abhay Kumar Padiwal M 2744 Bangalore Bangalore Bangalore 6 Abhay Kumar Payappa Vaghe 6909 Sadalaga Chikkodi Belagavi 591 239 7 Abhay Prasad 4725 Nagarabavi Bangalore Bangalore 560 072 8 Abhay Sridhar Rokhade 3867 Deshpande Nagar Hubli Dharwad 580 029 9 Abhay Vidyadhar Avalakki 5221 Patil Galli Angol Belagavi 590 006 10 Abhaya Bhupal Nagave 3282 Borgaon Chikkodi Belgaum 591216 11 Abhaya H.D. 7812 B.M Road Hassan Hassan 573 201 12 Abhaya Kumar Banappa Muggannavar 3414 Mahishavadagi Athani Belgaum 591240 13 Abhaya Kumar H D 198 Hassan Hassan Hassan 14 Abhaya Kumar S.A. 3244 Vijayanagar Bangalore Bangalore 560040 15 Abhaya Kumar Shanthinatha 2151 Harugeri Rayabag Belgaum Khemalapure 16 Abhaya Kumar Shreepal Karole 3279 Borgaon Chikkodi Belgaum 591216 17 Abhaya S Kagi Dr. 5448 Sindagi Sindagi Bijapur 586 128 18 Abhayachandra K 2779 Moodbidri Moodbidri Dakshina Kannada 19 Abhayakumar A.J. 7481 Vidyanagar Tumkur Tumkur 572 102 20 Abhayakumar Bhujabali Hardi 1717 Belgaum Belgaum Belgaum 21 Abhayakumar Jinagouda Koth 6503 Shamanewadi Chikkodi Belagavi 591 214 22 Abhayakumar Magadum 6465 R V College Bangalore Bangalore 560 059 23 Abhayakumar Mallappa Kaddu 7823 Kudachi Rayabagh Belagavi 591 311 24 Abhayakumar P 329 Bangalore Bangalore Bangalore 25 Abhayakumar P. -

Living Systems in Jainism: a Scientific Study

Living Systems in Jainism: A Scientific Study Narayan Lal Kachhara Kundakunda Jñānapīṭha, Indore i Living Systems in Jainism: A Scientific Study Author : Narayan Lal Kachhara, 55, Ravindra Nagar, Udaipur - 313003 [email protected] © Author ISBN: : 81-86933–62-X First Edition : 2018 Price : Rs. 350/- $ 10.00/- Publisher : Kundakunda Jñānapīṭha 584, M.G. Road, Tukoganj Indore – 452 001, India 0731 – 2545421, 2545744 [email protected] Financial support : Manohardevi Punamchand Kachhara Charitable Trust, Udaipur Printed at : Payorite Print Media Pvt. Ltd. Udaipur ii Dedicated to My son Raju Whose departure proved a turning point in my life That changed the course from Professionalism to spiritualism iii Publisher’s Note Sacred books written or compiled by Jain Acharyas are the rich source of knowledge. These texts and the commentaries written by later Acharyas are now being studied by monks and scholars in various contexts. These sources provide us guidelines and directions for meaningful living, searching the purpose of life and knowing the nature and its interactions with the living beings. The religious texts are studied from the following points of views: 1. Spiritual. The texts were primarily composed for giving the human beings the knowledge for making spiritual progress ultimately leading to the state of permanent bliss. 2. History. The texts provide historical information about the ancient period. 3. Culture and art. The texts contain information on culture and art of those times. 4. Science. The texts contain a treasure of knowledge about the realities of nature and its interaction with the life of living beings. This branch of knowledge earlier studied as philosophy is now known as science. -

Visualizing Yakshi in the Religious History of Kerala

Visualizing Yakshi in the Religious History of Kerala Sandhya M. Unnikrishnan1 1. Department of History, NSS College Manjeri, Malappuram, Kerala, India (Email: [email protected]) Received: 30 October 2017; Revised: 24 November 2017; Accepted: 18 December 2017 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 5 (2017): 757‐777 Abstract: Yakshi is a female goddess associated with the fertility of earth, love and beauty. She probably originated with the early Dravidians but have subsequently been absorbed in to the imagery of Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism. She has been worshipped since pre historic times in Indian. The roles and functions of this deity went through dramatic changes over period of time. The cult is closely associated with the primitive mode of worship even before the development of philosophy and theological doctrines in the Hindu fold. This paper intends to analyse the development of Yakshi cult in Kerala and its prevalence in Kerala society. The cult points of this deity are placed along the land routes of trade leading from Karnataka and Tamil Nadu into Kerala. A detailed survey of the midlands and low lands of Kerala testifies that the cult points were located along the water highways and interior land routes starting from the Western Ghats to Arabian Sea. The cult is closely interlinked with the Gramadevatha concept and with folk deities. Keywords: Yakshi, Fertility, Cult Points, Jainism, Gramadevatha, Folk Deities, Kavu Introduction The word Yaksha, literally means somebody shining, may allude to human beings shining wealth and fame or superhuman beings shining with virtues. Yakshi may be regarded as the embodiment of feminine beauty.