Jwalamalini Cult and Jainism in Kerala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism & Jainism in Early Historic Asia Iconography of Parshvanatha

Buddhism & Jainism in Early Historic Asia Iconography of Parshvanatha at Annigere in North Karnataka – An Analysis Dr. Soumya Manjunath Chavan* India being the country which is known to have produced three major religions of the world: Hinduism, Budhism and Jainism. Jainism is still a practicing religion in many states of India like Gujarat, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan. The name Jaina is derived from the word jina, meaning conqueror, or liberator. Believing in immortal and indestructible soul (jiva) within every living being, it’s final goal is the state of liberation known as kaivalya, moksha or nirvana. The sramana movements rose in India in circa 550 B.C. Jainism in Karnataka began with the stable connection of the Digambara monk called Simhanandi who is credited with the establishment of the Ganga dynasty around 265 A.D. and thereafter for almost seven centuries Jain communities in Karnataka enjoyed the continuous patronage of this dynasty. Chamundaraya, a Ganga general commissioned the colossal rock- hewn statue of Bahubali at Sravana Belagola in 948 which is the holiest Jain shrines today. Gangas in the South Mysore and Kadambas and Badami Chalukyans in North Karnataka contributed to Jaina Art and Architecture. The Jinas or Thirthankaras list to twenty-four given before the beginning of the Christian era and the earliest reference occurs in the Samavayanga Sutra, Bhagavati Sutra, Kalpasutra and Pumacariyam. The Kalpasutra describes at length only the lives of Rishabhanatha, Neminatha, Parshvanatha and Mahavira. The iconographic feature of Parsvanatha was finalised first with seven-headed snake canopy in the first century B.C. -

The Rattas Patronage to Jainism

Aayushi International Interdisciplinary Research Journal (AIIRJ) UGC Approved Sr.No.64259 Vol - V Issue-I JANUARY 2018 ISSN 2349-638x Impact Factor 4.574 The Rattas Patronage to Jainism Dr.S.G. Chalawadi Asst. Professor, Dept of A I History and Epigraphy Karnatak University, Dharwad The Rattas were the significant ruling dynasty, who claimed descent from the Rastrakutas. The earliest record is dated 980 A.D. It comes from the place called sogal. It is believed that sogal was their early capital, from where they shifted first to Soundatti and later on to Belgaum. Their reign continued till 1238 A.D.1 When they were thrown out of power by the seunas of Devagiri. The Rattas served under the Chalukyas of Kalyan and tried to become independent. When the Kalachuries displaced 'the Chalukyas generally the Rattas claimed authority over a large administrative division known as Kohundi or kondi 3000. This included major parts of Soundatti, Gokak, Hukkeri, Raibag, Chikkodi, Bailhongal and Mudhol, Jamakhandi talukas which fall in Belgaum and Bijapur districts. The line of descent of Rattas rulers, commences with Nanna and ends with Lakshmideva - II. In between there were eleven rulers, namely Karthavirya-I, Nanna - I, Erga, Anka, Nanna-II, Karthavirya II, Sena-II, Karthavirya-III, Lakshmideva-I, Karthavirya-IV and Mallikarjuna- II. The Rattas in the course of their rule patronaged both saivism and Jainism. By erecting temples and Basadis and giving much grants to them. One of the earliest references to Jaina patronage under the Rattas is noticed in Soundatti inscription. We are told that Karthavirya-I gave land (grants) to the Basadis constructed by Pritvirama his successors Kannakaira also gave grants to Jinalya at Soundatti. -

Life of Mahavira As Described in the Jai N a Gran Thas Is Imbu Ed with Myths Which

T o be h a d of 1 T HE MA A ( ) N GER , T HE mu Gu ms J , A llahaba d . Lives of greatmen all remin d u s We can m our v s su m ake li e bli e , A nd n v hi n u s , departi g , lea e be d n n m Footpri ts o the sands of ti e . NGF LL W LO E O . mm zm fitm m m ! W ‘ i fi ’ mz m n C NT E O NT S. P re face Introd uction ntrod uctor remar s and th i I y k , e h storicity of M ahavira Sources of information mt o o ica stories , y h l g l — — Family relations birth — — C hild hood e d ucation marriage and posterity — — Re nou ncing the world Distribution of wealth Sanyas — — ce re mony Ke sh alochana Re solution Seve re pen ance for twe lve years His trave ls an d pre achings for thirty ye ars Attai n me nt of Nirvan a His disciples and early followers — H is ch aracte r teachings Approximate d ate of His Nirvana Appendix A PREF CE . r HE primary con dition for th e formation of a ” Nation is Pride in a common Past . Dr . Arn old h as rightly asked How can th e presen t fru th e u u h v ms h yield it , or f t re a e pro i e , except t eir ” roots be fixed in th e past ? Smiles lays mu ch ’ s ss on h s n wh n h e s s in his h a tre t i poi t , e ay C racter, “ a ns l n v u ls v s n h an d N tio , ike i di id a , deri e tre gt su pport from the feelin g th at they belon g to an u s u s h h th e h s of h ill trio race , t at t ey are eir t eir n ss an d u h u s of h great e , o g t to be perpet ator t eir is of mm n u s im an h n glory . -

Lord Mahavira Publisher's Note

LORD MAHAVIRA [A study in Historical Perspective] BY BOOL CHAND, M.A. Ph.D (Lond.) P. V. Research Institute Series: 39 Editor: Dr. Sagarmal Jain With an introduction by Prof. Sagarmal Jain P.V. RESEARCH INSTITUTE Varanasi-5 Published by P.V. Research Institute I.T.I. Road Varanasi-5 Phone:66762 2nd Edition 1987 Price Rs.40-00 Printed by Vivek Printers Post Box No.4, B.H.U. Varanasi-5 PUBLISHER’S NOTE 1 Create PDF with PDF4U. If you wish to remove this line, please click here to purchase the full version The book ‘Lord Mahavira’, by Dr. Bool Chand was first published in 1948 by Jaina Cultural Research Society which has been merged into P.V. Research Institute. The book was not only an authentic piece of work done in a historical perspective but also a popular one, hence it became unavailable for sale soon. Since long it was so much in demand that we decided in favor of brining its second Edition. Except some minor changes here and there, the book remains the same. Yet a precise but valuable introduction, depicting the relevance of the teachings of Lord Mahavira in modern world has been added by Dr. Sagarmal Jain, the Director, P.V. Research Institute. As Dr. Jain has pointed out therein, the basic problems of present society i.e. mental tensions, violence and the conflicts of ideologies and faith, can be solved through three basic tenets of non-attachment, non-violence and non-absolutism propounded by Lord Mahavira and peace and harmony can certainly be established in the world. -

Impact Factor 3.025

AayushiImpact International Interdisciplinary Research Journal (AIIRJ) Factor UGC Approved Sr.No.64259 ISSN 2349-638x Vol - IV 3Issue.025-XII DECEMBER 2017 ISSN 2349-638x Impact Factor 3.025 Refereed And Indexed Journal AAYUSHI INTERNATIONAL INTERDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH JOURNAL (AIIRJ) UGC Approved Monthly Journal VOL-IV ISSUE-XII Dec. 2017 •Vikram Nagar, Boudhi Chouk, Latur. Address •Tq. Latur, Dis. Latur 413512 (MS.) •(+91) 9922455749, (+91) 8999250451 •[email protected] Email •[email protected] Website •www.aiirjournal.com Email id’s:- [email protected] EDITOR,[email protected] – PRAMOD PRAKASHRAO I Mob.08999250451 TANDALE Page website :- www.aiirjournal.com l UGC Approved Sr.No.64259 No. 121 Aayushi International Interdisciplinary Research Journal (AIIRJ) UGC Approved Sr.No.64259 Vol - IV Issue-XII DECEMBER 2017 ISSN 2349-638x Impact Factor 3.025 Jain Centres In Chikodi Taluka Dr. S.G. Chalawadi Asst. Professor, Dept. of A.I.Histoty and Epi. K.U.D. Dharwad Email ID: [email protected] Jainism is one of the earliest religions in Chikodi taluka. Jainisim made its entry in the pre- Christian era. Inscriptions revealed that Jaina saints came to preach the doctrines of the religion in about 225 B.C.1 Jainism was a very popular religion from 4th to 13th century because many dynasties of this period belonged to Jainism and it declined subsequently due to spread of Shaivism and Veerashaivism.Many Jinalayas were converted into Shaivalayas, Vaishanvalayas and Gramadevi temples. For instance, one Adinatha basati built by Kamalapure family of Kabbur was converted into Shaiva temple. As records were destroyed, it is very difficult to recognize it as basati.2 Six percent of Jains are found in this region. -

Nonviolence in the Hindu, Jain and Buddhist Traditions Dr

1 Nonviolence in the Hindu, Jain and Buddhist traditions Dr. Vincent Sekhar, SJ Arrupe Illam Arul Anandar College Karumathur – 625514 Madurai Dt. INDIA E-mail: [email protected] Introduction: Religion is a human institution that makes sense to human life and society as it is situated in a specific human context. It operates from ultimate perspectives, in terms of meaning and goal of life. Religion does not merely provide a set of beliefs, but offers at the level of behaviour certain principles by which the believing community seeks to reach the proposed goals and ideals. One of the tasks of religion is to orient life and the common good of humanity, etc. In history, religion and society have shaped each other. Society with its cultural and other changes do affect the external structure of any religion. And accordingly, there might be adaptations, even renewals. For instance, religions like Buddhism and Christianity had adapted local cultural and traditional elements into their religious rituals and practices. But the basic outlook of Buddhism or Christianity has not changed. Their central figures, tenets and adherence to their precepts, etc. have by and large remained the same down the history. There is a basic ethos in the religious traditions of India, in Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism. Buddhism may not believe in a permanent entity called the Soul (Atman), but it believes in the Act (karma), the prime cause for the wells or the ills of this world and of human beings. 1 Indian religions uphold the sanctity of life in all its forms and urge its protection. -

Sculptural Art of Jains in Odisha: a Study

International Journal of Humanities And Social Sciences (IJHSS) ISSN (P): 2319-393X; ISSN (E): 2319-3948 Vol. 6, Issue 4, Jun - Jul 2017; 115 - 126 © IASET SCULPTURAL ART OF JAINS IN ODISHA: A STUDY AKHAYA KUMAR MISHRA Lecturer in History, Balugaon College, Balugaon, Khordha, Odisha, India ABSTRACT In ancient times, Odisha was known as Utkal, which means utkarsh in kala i.e., excellent in the arts. Its rich artistic legacy permeates through time, into modern decor, never deviating from the basics. Each motif or intricate pattern, draws its inspiration from a myth or folklore, or from the general ethos itself. Covered by the dense forests, soaring mountains, sparkling waterfalls, murmuring springs, gurgling rivers, secluded dales, deep valleys, captivating beaches and sprawling lake, Odisha is a kaleidoscope of past splendor and present glory. Being the meeting place of Aryan and Dravidian cultures, with is delightful assimilations, from the fascinating lifestyle of the tribes, Odisha retains in its distinct identity, in the form of sculptural art, folk art and performing art. The architectural wonders of Odisha must be seen in the Jain caves, which speak about the fine artistry of Odisha’s craftsmen, in the bygone era. The Odias displayed their remarkable creative power, in the Jain sculptural art. While they built their caves like giants, they sculptured the caves like master artists. The theme of these sculptures was so varied, for the artist and his imagination so deep that, as if, he was writing an epic on the surface of the stone. KEYWORDS: Art, Architecture, Sculpture, Prolific INTRODUCTION Odisha has a rich and unique heritage of art traditions, beginning from the sophisticated ornate temple architecture, and sculpture to folk arts, in different forms. -

Jain Philosophy and Practice I 1

PANCHA PARAMESTHI Chapter 01 - Pancha Paramesthi Namo Arihantänam: I bow down to Arihanta, Namo Siddhänam: I bow down to Siddha, Namo Äyariyänam: I bow down to Ächärya, Namo Uvajjhäyänam: I bow down to Upädhyäy, Namo Loe Savva-Sähunam: I bow down to Sädhu and Sädhvi. Eso Pancha Namokkäro: These five fold reverence (bowings downs), Savva-Pävappanäsano: Destroy all the sins, Manglänancha Savvesim: Amongst all that is auspicious, Padhamam Havai Mangalam: This Navakär Mantra is the foremost. The Navakär Mantra is the most important mantra in Jainism and can be recited at any time. While reciting the Navakär Mantra, we bow down to Arihanta (souls who have reached the state of non-attachment towards worldly matters), Siddhas (liberated souls), Ächäryas (heads of Sädhus and Sädhvis), Upädhyäys (those who teach scriptures and Jain principles to the followers), and all (Sädhus and Sädhvis (monks and nuns, who have voluntarily given up social, economical and family relationships). Together, they are called Pancha Paramesthi (The five supreme spiritual people). In this Mantra we worship their virtues rather than worshipping any one particular entity; therefore, the Mantra is not named after Lord Mahävir, Lord Pärshva- Näth or Ädi-Näth, etc. When we recite Navakär Mantra, it also reminds us that, we need to be like them. This mantra is also called Namaskär or Namokär Mantra because in this Mantra we offer Namaskär (bowing down) to these five supreme group beings. Recitation of the Navakär Mantra creates positive vibrations around us, and repels negative ones. The Navakär Mantra contains the foremost message of Jainism. The message is very clear. -

Kalarippayat

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/65537 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-07 and may be subject to change. Kalarippayat The structure and essence of an Indian martial art D.H. Luijendijk Kalarippayat The Structure and Essence of an Indian Martial Art Een wetenschappelijke proeve op het gebied van de Religiewetenschappen Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. mr. S.C.J.J. Kortmann volgens besluit van het College van Decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 16 april 2008 om 15.30 uur precies door Dick Hidde Luijendijk geboren op 19 juni 1971 te Gouda Promotor: Prof. dr. W. Dupré Copromotor: Dr. P.J.C.L. van der Velde Manuscriptcommissie: Prof. dr. G. Essen Prof. dr. W.M. Callewaert (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven) Dr. F.L. Bakker (Universiteit Utrecht) CIP-GEGEVENS KONINKLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK, DEN HAAG © Copyright D.H. Luijendijk 2007 Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets uit deze uitgave mag zonder schriftelijke toestemming van de auteur worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij electronisch, mechanisch, door fotokopieen, opnamen, of op enig andere manier. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the author. -

Vol. No. 99 September, 2008 Print "Ahimsa Times "

AHIMSA TIMES - SEPTEMBER 2008 ISSUE - www.jainsamaj.org Page 1 of 22 Vol. No. 99 Print "Ahimsa Times " September, 2008 www.jainsamaj.org Board of Trustees Circulation + 80000 Copies( Jains Only ) Email: Ahimsa Foundation [email protected] New Matrimonial New Members Business Directory PARYUSHAN PARVA Paryushan Parva is an annual religious festival of the Jains. Considered auspicious and sacred, it is observed to deepen the awareness as a physical being in conjunction with spiritual observations Generally, Paryushan Parva falls in the month of September. In Jainisim, fasting is considered as a spiritual activity, that purify our souls, improve morality, spiritual power, increase knowledge and strengthen relationships. The purpose is to purify our souls by staying closer to our own souls, looking at our faults and asking for forgiveness for the mistakes and taking vows to minimize our faults. Also a time when Jains will review their action towards their animals, environment and every kind of soul. Paryashan Parva is an annual, sacred religious festivals of the Jains. It is celebrated with fasting reading of scriptures, observing silence etc preferably under the guidance of monks in temples Strict fasting where one has to completely abstain from food and even water is observed for a week or more. Depending upon one's capability, complete fasting spans between 8-31 days. Religious and spiritual discourses are held where tales of Lord Mahavira are narrated. The Namokar Mantra is chanted everyday. Forgiveness in as important aspect of the celebration. At the end of Fasting, al will ask for forgiveness for any violence or wrong- doings they may have imposed previous year. -

Depiction of Yaksha and Yakshi's in Jainism

International Journal of Applied Research 2016; 2(2): 616-618 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Impact Factor: 5.2 Depiction of Yaksha and Yakshi’s in Jainism IJAR 2016; 2(2): 616-618 www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 13-12-2015 Dr. Venkatesha TS Accepted: 15-01-2016 Jainism, one of the oldest living faiths of India, has a hoary antiquity in Karnataka. No doubt, Dr. Venkatesha TS UGC-POST Doctoral Fellow this religion took its birth in North India. However, within a couple of centuries of its birth, Department of Studies and this religionis said to have entered into Karnataka. Jaina tradition ascribes III C.B.C. as the Research in History and date of entry of this religion to south India, and in particular to Karnataka. After this period Archaeology Tumkur Jainism grew from strength to strength and heralded a glorious era, never to be witnessed in University, Tumkur-572103 any part of India, to become a religion next only to Brahmanism in popularity and number. Though Jainism was spread over different parts of south India within the first few centuries of the Christian era, its nucleus as well as the stronghold was southern Karnataka. In fact, it is the general opinion that the history of Jainism in south India is predominantly the history of that religion in Karnataka. Such was the prominence that this religion enjoyed throughout the first millennium A.D. Liberal royal patronage extended by the Kadambas, the Gangas, the Chalukyas of Badami, the Rashtrakutas, the Nolambas, the Kalyana Chalukyas, the Hoysalas, the Vijayanagar rulers and their successors, resulted in the uninterrupted growth of this religion in southern Karnataka. -

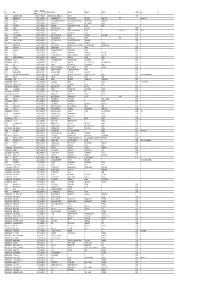

Mgl-Di419-Unpaid Shareholder List As On

DIVIDEND WARRANT KEY NAME MICR DDNO ADDRESS 1 ADDRESS 2 ADDRESS 3 ADDRESS 4 CITY PINCODE JH1 JH2 AMOUNT NO 001221 DWARKA NATH ACHARYA 220000.00 194000027 843427 5 JAG BANDHU BORAL LANE CALCUTTA 700007 000642 JNANAPRAKASH P.S. 2200.00 194000030 536 POZHEKKADAVIL HOUSE P.O.KARAYAVATTAM TRICHUR DIST. KERALA STATE 68056 MRS. LATHA M.V. 000691 BHARGAVI V.R. 2200.00 194000031 537 C/O K.C.VISHWAMBARAN,P.B.NO.63 ADV.KAYCEE & KAYCEE AYYANTHOLE TRICHUR DISTRICT KERALA STATE 002670 SUNIL P K 6600.00 194000040 546 PARAMEL HOUSE CHIRAKKACODE VELLANIKKARA P O THRISSUR 002679 NARAYANAN P S 2200.00 194000041 547 PANAT HOUSE P O KARAYAVATTOM, VALAPAD THRISSUR KERALA 002809 GIREESH C T 2200.00 194000045 551 CHERIYA THOTTUNGAL H ICE ROAD VATAKARA-3 000000 003124 VENUGOPAL M R 2200.00 194000048 554 MOOTHEDATH (H) SAWMILL ROAD KOORVENCHERY THRISSUR GEETHADEVI M V 000000 RISHI M.V. 003292 SURENDARAN K K 2068.00 194000050 556 KOOTTALA (H) PO KOOKKENCHERY THRISSUR 000000 003442 POOKOOYA THANGAL 2068.00 194000053 559 MECHITHODATHIL HOUSE VELLORE PO POOKOTTOR MALAPPURAM 000000 003445 CHINNAN P P 2200.00 194000054 560 PARAVALLAPPIL HOUSE KUNNAMKULAM THRISSUR PETER P C 000000 001431 JITENDRA DATTA MISRA 6600.00 194000065 571 BHRATI AJAY TENAMENTS 5 VASTRAL RAOD WADODHAV PO AHMEDABAD 382415 IN30177410163576 Rukaiya Kirit Joshi 2695.00 194000081 587 303 Anand Shradhanand Road Vile Parle East Mumbai 400057 001012 SHARAVATHY C.H. 2200.00 194000088 594 W/O H.L.SITARAMAN, 15/2A,NAV MUNJAL NAGAR,HOUSING CO-OPERATIVE SOCIETY CHEMBUR, MUMBAI 400089 001424 BALARAMAN S N 11000.00 194000112 618 14 ESOOF LUBBAI ST TRIPLICANE MADRAS 600005 002473 GUNASEKARAN V 5500.00 194000114 620 NO.5/1324,18TH MAIN ROAD ANNA NAGAR WEST CHENNAI 600040 000697 AMALA S.