It Is Obvious That the Time-Honored Medium of the String Quartet Will Never Become a Relic of the Past. the Evolution of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parma Manifesto Frederic Rzewski

COMPOSER’S NOTEBOOK Parma Manifesto Frederic Rzewski I This text, Parma Manifesto, was written in the afternoon of a American-born and -raised composer and musician Frederic D E performance by Musica Elletronica Viva (MEV)—the Rome-based Rzewski began his career as a performer of new piano music in Italy N T electronic music and improvisation group that Rzewski had recently during the 1960s. His early associations with the composers Chris- I T co-founded—in March 1968 at the Festival Internazionale del Teatro tian Wolff, David Behrman, John Cage and David Tudor strongly Y Universitario in Parma, Italy. The evening performance, directed by influenced his compositional style and performance practice. He Jean-Jacques Lebel, although basically spontaneous, mainly had to do formed MEV in the mid-1960s with Alvin Curran and Richard with the necessity of taking theater out into the streets. It was termi- Teitelbaum in order to explore possibilities in live electronics and col- nated by the authorities, who simply turned off the electricity. The per- lective improvisation. Over the past three decades his work has been formers and audience carried the performance out of the theater. The performed across the U.S.A. and Europe, and he has taught composi- next day, the students occupied the University. MEV was involved in tion in the U.S., Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands. a number of similar incidents at that time. Works published as Composer’s Notebook entries in Leonardo Music Journal may include composers’ texts published in raw, unedited form, scores, working notes, schematics, diagrams or Frederic Rzewski (musician, composer), 142 Meyerbear, 1180 Brussels, Belgium. -

Occam's Razor Vol. 3 - Full (2013)

Occam's Razor Volume 3 (2013) Article 1 2013 Occam's Razor Vol. 3 - Full (2013) Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/orwwu Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons, Biology Commons, Comparative Politics Commons, Exercise Science Commons, Forest Biology Commons, Macroeconomics Commons, and the Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation (2013) "Occam's Razor Vol. 3 - Full (2013)," Occam's Razor: Vol. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/orwwu/vol3/iss1/1 This Complete Volume is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Student Publications at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occam's Razor by an authorized editor of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. et al.: Vol. 3, 2013 Published by Western CEDAR, 2017 1 Occam's Razor, Vol. 3 [2017], Art. 1 occam’s razor OCCAM’S RAZOR OCCAM’S RAZOR occam’s razor CONTENTS spring 2013 Vol. 3 03 EDITOR IN CHIEF OUR SINCEREST GRATITUDE TO; FORWARD cameron adams glen tokola Chris Crow and Cameron Adams for having pioneered this journal. MANAGING EDITOR 05 REANIMATING IDENTITIES mckenzie yuasa sarah elder The Faculty Senate for providing Occam’s Razor WWU the the zombie manifestion ASSOCIATE EDITORS opportunity to be formally introduced to the departments of Western. of a darker america megan cook Rebecca Marrall, for her continued support in advising the journal. olivia henry 11 DARK CITY: rebecca ortega sophie logan Victor Celis, ASWWU Vice President for Academic Affairs, for his memories all alone support in our efforts to establish the journal’s presence. -

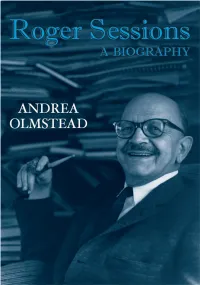

Roger Sessions: a Biography

ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Recognized as the primary American symphonist of the twentieth century, Roger Sessions (1896–1985) is one of the leading representatives of high modernism. His stature among American composers rivals Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, and Elliott Carter. Influenced by both Stravinsky and Schoenberg, Sessions developed a unique style marked by rich orchestration, long melodic phrases, and dense polyphony. In addition, Sessions was among the most influential teachers of composition in the United States, teaching at Princeton, the University of California at Berkeley, and The Juilliard School. His students included John Harbison, David Diamond, Milton Babbitt, Frederic Rzewski, David Del Tredici, Conlon Nancarrow, Peter Maxwell Davies, George Tson- takis, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, and many others. Roger Sessions: A Biography brings together considerable previously unpublished arch- ival material, such as letters, lectures, interviews, and articles, to shed light on the life and music of this major American composer. Andrea Olmstead, a teaching colleague of Sessions at Juilliard and the leading scholar on his music, has written a complete bio- graphy charting five touchstone areas through Sessions’s eighty-eight years: music, religion, politics, money, and sexuality. Andrea Olmstead, the author of Juilliard: A History, has published three books on Roger Sessions: Roger Sessions and His Music, Conversations with Roger Sessions, and The Correspondence of Roger Sessions. The author of numerous articles, reviews, program and liner notes, she is also a CD producer. This page intentionally left blank ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Andrea Olmstead First published 2008 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2008 Andrea Olmstead Typeset in Garamond 3 by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk All rights reserved. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

2012 02 20 Programme Booklet FIN

COMPOSITION - EXPERIMENT - TRADITION: An experimental tradition. A compositional experiment. A traditional composition. An experimental composition. A traditional experiment. A compositional tradition. Orpheus Research Centre in Music [ORCiM] 22-23 February 2012, Orpheus Institute, Ghent Belgium The fourth International ORCiM Seminar organised at the Orpheus Institute offers an opportunity for an international group of contributors to explore specific aspects of ORCiM's research focus: Artistic Experimentation in Music. The theme of the conference is: Composition – Experiment – Tradition. This two-day international seminar aims at exploring the complex role of experimentation in the context of compositional practice and the artistic possibilities that its different approaches yield for practitioners and audiences. How these practices inform, or are informed by, historical, cultural, material and geographical contexts will be a recurring theme of this seminar. The seminar is particularly directed at composers and music practitioners working in areas of research linked to artistic experimentation. Organising Committee ORCiM Seminar 2012: William Brooks (U.K.), Kathleen Coessens (Belgium), Stefan Östersjö (Sweden), Juan Parra (Chile/Belgium) Orpheus Research Centre in Music [ORCiM] The Orpheus Research Centre in Music is based at the Orpheus Institute in Ghent, Belgium. ORCiM's mission is to produce and promote the highest quality research into music, and in particular into the processes of music- making and our understanding of them. ORCiM -

The Ten String Quartets of Ben Johnston, Written Between 1951 and 1995, Constitute No Less Than an Attempt to Revolutionize the Medium

The ten string quartets of Ben Johnston, written between 1951 and 1995, constitute no less than an attempt to revolutionize the medium. Of them, only the First Quartet limits itself to conventional tuning. The others, climaxing in the astonishing Seventh Quartet of 1984, add in further microtones from the harmonic series to the point that the music seems to float in a free pitch space, unmoored from the grid of the common twelve-pitch scale. In a way, this is a return to an older conception of string quartet practice, since players used to (and often still do) intuitively adjust their tuning for maximum sonority while listening to each other’s intonation. But Johnston has extended this practice in two dimensions: Rather than leave intonation to the performer’s ear and intuition, he has developed his own way to specify it in notation; and he has moved beyond the intervals of normal musical practice to incorporate increasingly fine distinctions, up to the 11th, 13th, and even 31st partials in the harmonic series. This recording by the indomitable Kepler Quartet completes the series of Johnston’s quartets, finally all recorded at last for the first time. Volume One presented Quartets 2, 3, 4, and 9; Volume Two 1, 5, and 10; and here we have Nos. 6, 7, and 8, plus a small piece for narrator and quartet titled Quietness. As Timothy Ernest Johnson has documented in his exhaustive dissertation on Johnston’s Seventh Quartet, Johnston’s string quartets explore extended tunings in three phases.1 Skipping over the more conventional (though serialist) First Quartet, the Second and Third expand the pitch spectrum merely by adding in so-called five-limit intervals (thirds, fourths, and fifths) perfectly in tune (which means unlike the imperfect, compromised way we tune them on the modern piano). -

ANNIE GOSFIELD, Whom the BBC Called “A One Woman Hadron

ANNIE GOSFIELD, whom the BBC called “A one woman Hadron collider,” lives in New York City and works on the boundaries between notated and improvised music, electronic and acoustic sounds, refined timbres and noise. Her music is often inspired by the inherent beauty of found sounds, noise, and machinery. She was dubbed “a master of musical feedback” by The New York Times, who wrote “Ms. Gosfield’s choice of sounds — which on this occasion included radio static, the signals transmitted by the Soviet satellite Sputnik I, and recordings of Hurricane Sandy — are never a mere gimmick. Her extraordinary command of texture and timbre means that whether she is working with a solo cello or with the ensemble she calls her “21st-century avant noisy dream band,” she is able to conjure up a palette of saturated and heady hues.” In 2017 Gosfield collaborated with Yuval Sharon and the Los Angeles Philharmonic on the multi-site opera “War of the Worlds.” This large-scale, citywide collaborative performance was a powerful engagement with public life, bringing opera out of the concert hall and into the streets. Three defunct air raid sirens located in downtown Los Angeles were re-purposed into public speakers to broadcast a free, live performance from Walt Disney Concert Hall. The sirens also served as remote sites for singers and musicians to report back to the concert hall from the street. The notorious 1938 radio drama created by Orson Welles came to new life, directed by The Industry’s Yuval Sharon, conducted by Christopher Rountree and narrated by Sigourney Weaver. -

Pieces for Piano Cristina Spinei Mechanical Angels Reflections Relics the Road Frederic Rzewski Mile 47

Pieces for Piano Cristina Spinei Mechanical Angels Reflections Relics The Road Frederic Rzewski Mile 47, “Walk in the Woods (b. 1938) Mile 48, “Why” The People United Will Never Be Defeated! 36 Variations on ¡El pueblo unido jamás será vencido! Matthew Phelps is one of the most versatile classical musicians in the nation. He is a sought-after performer as a pianist and conductor. He has performed recitals for the Nashville Cathedral Arts Series, Steinway Society of Nashville, Nashville Symphony’s On Stage series, Wright State University, the University of Dayton, the Music at 990 series, and has appeared numerous times on Nashville Public Radio as a soloist and chamber musician. He has performed as a soloist with the Nashville Concerto Orchestra, Intersection, and participated in a complete performance of Beethoven’s 32 piano sonatas, where he and 20 other pianists performed Beethoven’s works in chronological order as part of a two-day festival. A proponent of new music and classical improvisation, Phelps is known for his performances of Frederic Rzweksi’s monumental, “The People United Will Never Defeated,” which he has played throughout the nation including a 2019 tour of California. He has also premiered music by Christina Spinei, Peter Morabito, Drew Dolan, David Macdonald, Dan Locklair, Dominick DiOrio. Phelps is active as a chamber musician, often playing with Erin Hall and Keith Nicholas as a founding member of the Elliston Trio. The trio has played throughout the nation in a repertoire that spans from Mozart to Joan Tower. Their performance of the Triple Concerto, under the baton of Earl Rivers, concluded Nashville’s Beethoven festival. -

Electronic Music

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Research Repository @ WVU (West Virginia University) Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Rethinking Interaction: Identity and Agency in the Performance of “Interactive” Electronic Music Jacob A. Kopcienski Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Musicology Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Kopcienski, Jacob A., "Rethinking Interaction: Identity and Agency in the Performance of “Interactive” Electronic Music" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7493. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7493 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rethinking Interaction: Identity and Agency in the Performance of “Interactive” Electronic Music Jacob A. Kopcienski Thesis submitted To the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Musicology Travis D. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 1964 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation RCA Victor R£D SEAL festival of Contemporary American Composers DELLO JOIO: Fantasy and Variations/Ravel: Concerto in G Hollander/Boston Symphony Orchestra/Leinsdorf LM/LSC-2667 COPLAND: El Salon Mexico Grofe-. Grand Canyon Suite Boston Pops/ Fiedler LM-1928 COPLAND: Appalachian Spring The Tender Land Boston Symphony Orchestra/ Copland LM/LSC-240i HOVHANESS: BARBER: Mysterious Mountain Vanessa (Complete Opera) Stravinsky: Le Baiser de la Fee (Divertimento) Steber, Gedda, Elias, Mitropoulos, Chicago Symphony/Reiner Met. Opera Orch. and Chorus LM/LSC-2251 LM/LSC-6i38 FOSS: IMPROVISATION CHAMBER ENSEMBLE Studies in Improvisation Includes: Fantasy & Fugue Music for Clarinet, Percussion and Piano Variations on a Theme in Unison Quintet Encore I, II, III LM/LSC-2558 RCA Victor § © The most trusted name in sound BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH Leinsdorf, Director Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Richard Burgin, Associate Chairman of the Faculty Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director DEPARTMENT OF COMPOSITION Aaron Copland, Head Gunther Schuller, Acting Head Arthur Berger and Lukas Foss, Guest Teachers Paul Jacobs, Fromm Instructor in Contemporary Music Stanley Silverman and David Walker, Administrative Assistants The Berkshire Music Center is the center for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager BALDWIN PIANO RCA VICTOR RECORDS — 1 PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC Participants in this year's Festival are invited to subscribe to the American journal devoted to im- portant issues of contemporary music. -

Tuning in Opposition

TUNING IN OPPOSITION: THE THEATER OF ETERNAL MUSIC AND ALTERNATE TUNING SYSTEMS AS AVANT-GARDE PRACTICE IN THE 1960’S Charles Johnson Introduction: The practice of microtonality and just intonation has been a core practice among many of the avant-garde in American 20th century music. Just intonation, or any system of tuning in which intervals are derived from the harmonic series and can be represented by integer ratios, is thought to have been in use as early as 5000 years ago and fell out of favor during the common practice era. A conscious departure from the commonly accepted 12-tone per octave, equal temperament system of Western music, contemporary music created with alternate tunings is often regarded as dissonant or “out-of-tune,” and can be read as an act of opposition. More than a simple rejection of the dominant tradition, the practice of designing scales and tuning systems using the myriad options offered by the harmonic series suggests that there are self-deterministic alternatives to the harmonic foundations of Western art music. And in the communally practiced and improvised performance context of the 1960’s, the use of alternate tunings offers a Johnson 2 utopian path out of the aesthetic dead end modernism had reached by mid-century. By extension, the notion that the avant-garde artist can create his or her own universe of tonality and harmony implies a similar autonomy in defining political and social relationships. In the early1960’s a New York experimental music performance group that came to be known as the Dream Syndicate or the Theater of Eternal Music (TEM) began experimenting with just intonation in their sustained drone performances. -

Newslist Drone Records 31. January 2009

DR-90: NOISE DREAMS MACHINA - IN / OUT (Spain; great electro- acoustic drones of high complexity ) DR-91: MOLJEBKA PVLSE - lvde dings (Sweden; mesmerizing magneto-drones from Swedens drone-star, so dense and impervious) DR-92: XABEC - Feuerstern (Germany; long planned, finally out: two wonderful new tracks by the prolific german artist, comes in cardboard-box with golden print / lettering!) DR-93: OVRO - Horizontal / Vertical (Finland; intense subconscious landscapes & surrealistic schizophrenia-drones by this female Finnish artist, the "wondergirl" of Finnish exp. music) DR-94: ARTEFACTUM - Sub Rosa (Poland; alchemistic beauty- drones, a record fill with sonic magic) DR-95: INFANT CYCLE - Secret Hidden Message (Canada; long-time active Canadian project with intelligently made hypnotic drone-circles) MUSIC for the INNER SECOND EDITIONS (price € 6.00) EXPANSION, EC-STASIS, ELEVATION ! DR-10: TAM QUAM TABULA RASA - Cotidie morimur (Italy; outerworlds brain-wave-music, monotonous and hypnotizing loops & Dear Droners! rhythms) This NEWSLIST offers you a SELECTION of our mailorder programme, DR-29: AMON – Aura (Italy; haunting & shimmering magique as with a clear focus on droney, atmospheric, ambient music. With this list coming from an ancient culture) you have the chance to know more about the highlights & interesting DR-34: TARKATAK - Skärva / Oroa (Germany; atmospheric drones newcomers. It's our wish to support this special kind of electronic and with a special touch from this newcomer from North-Germany) experimental music, as we think its much more than "just music", the DR-39: DUAL – Klanik / 4 tH (U.K.; mighty guitar drones & massive "Drone"-genre is a way to work with your own mind, perception, and sub bass undertones that evoke feelings of total transcendence and (un)-consciousness-processes.