The War Bond Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Guide to the educational resources available on the GHS website Theme driven guide to: Online exhibits Biographical Materials Primary sources Classroom activities Today in Georgia History Episodes New Georgia Encyclopedia Articles Archival Collections Historical Markers Updated: July 2014 Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Table of Contents Pre-Colonial Native American Cultures 1 Early European Exploration 2-3 Colonial Establishing the Colony 3-4 Trustee Georgia 5-6 Royal Georgia 7-8 Revolutionary Georgia and the American Revolution 8-10 Early Republic 10-12 Expansion and Conflict in Georgia Creek and Cherokee Removal 12-13 Technology, Agriculture, & Expansion of Slavery 14-15 Civil War, Reconstruction, and the New South Secession 15-16 Civil War 17-19 Reconstruction 19-21 New South 21-23 Rise of Modern Georgia Great Depression and the New Deal 23-24 Culture, Society, and Politics 25-26 Global Conflict World War One 26-27 World War Two 27-28 Modern Georgia Modern Civil Rights Movement 28-30 Post-World War Two Georgia 31-32 Georgia Since 1970 33-34 Pre-Colonial Chapter by Chapter Primary Sources Chapter 2 The First Peoples of Georgia Pages from the rare book Etowah Papers: Exploration of the Etowah site in Georgia. Includes images of the site and artifacts found at the site. Native American Cultures Opening America’s Archives Primary Sources Set 1 (Early Georgia) SS8H1— The development of Native American cultures and the impact of European exploration and settlement on the Native American cultures in Georgia. Illustration based on French descriptions of Florida Na- tive Americans. -

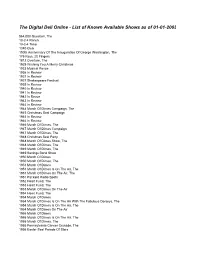

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows As of 01-01-2003

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows as of 01-01-2003 $64,000 Question, The 10-2-4 Ranch 10-2-4 Time 1340 Club 150th Anniversary Of The Inauguration Of George Washington, The 176 Keys, 20 Fingers 1812 Overture, The 1929 Wishing You A Merry Christmas 1933 Musical Revue 1936 In Review 1937 In Review 1937 Shakespeare Festival 1939 In Review 1940 In Review 1941 In Review 1942 In Revue 1943 In Review 1944 In Review 1944 March Of Dimes Campaign, The 1945 Christmas Seal Campaign 1945 In Review 1946 In Review 1946 March Of Dimes, The 1947 March Of Dimes Campaign 1947 March Of Dimes, The 1948 Christmas Seal Party 1948 March Of Dimes Show, The 1948 March Of Dimes, The 1949 March Of Dimes, The 1949 Savings Bond Show 1950 March Of Dimes 1950 March Of Dimes, The 1951 March Of Dimes 1951 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1951 March Of Dimes On The Air, The 1951 Packard Radio Spots 1952 Heart Fund, The 1953 Heart Fund, The 1953 March Of Dimes On The Air 1954 Heart Fund, The 1954 March Of Dimes 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air With The Fabulous Dorseys, The 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1954 March Of Dimes On The Air 1955 March Of Dimes 1955 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1955 March Of Dimes, The 1955 Pennsylvania Cancer Crusade, The 1956 Easter Seal Parade Of Stars 1956 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 Heart Fund, The 1957 March Of Dimes Galaxy Of Stars, The 1957 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 March Of Dimes Presents The One and Only Judy, The 1958 March Of Dimes Carousel, The 1958 March Of Dimes Star Carousel, The 1959 Cancer Crusade Musical Interludes 1960 Cancer Crusade 1960: Jiminy Cricket! 1962 Cancer Crusade 1962: A TV Album 1963: A TV Album 1968: Up Against The Establishment 1969 Ford...It's The Going Thing 1969...A Record Of The Year 1973: A Television Album 1974: A Television Album 1975: The World Turned Upside Down 1976-1977. -

The History of Sexuality, Volume 2: the Use of Pleasure

The Use of Pleasure Volume 2 of The History of Sexuality Michel Foucault Translated from the French by Robert Hurley Vintage Books . A Division of Random House, Inc. New York The Use of Pleasure Books by Michel Foucault Madness and Civilization: A History oflnsanity in the Age of Reason The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences The Archaeology of Knowledge (and The Discourse on Language) The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception I, Pierre Riviere, having slaughtered my mother, my sister, and my brother. ... A Case of Parricide in the Nineteenth Century Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison The History of Sexuality, Volumes I, 2, and 3 Herculine Barbin, Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a Nineteenth Century French Hermaphrodite Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977 VINTAGE BOOKS EDlTlON, MARCH 1990 Translation copyright © 1985 by Random House, Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in France as L' Usage des piaisirs by Editions Gallimard. Copyright © 1984 by Editions Gallimard. First American edition published by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., in October 1985. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Foucault, Michel. The history of sexuality. Translation of Histoire de la sexualite. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. Contents: v. I. An introduction-v. 2. The use of pleasure. I. Sex customs-History-Collected works. -

Thrift, Sacrifice, and the World War II Bond Campaigns

Saving for Democracy University Press Scholarship Online Oxford Scholarship Online Thrift and Thriving in America: Capitalism and Moral Order from the Puritans to the Present Joshua Yates and James Davison Hunter Print publication date: 2011 Print ISBN-13: 9780199769063 Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: May 2012 DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199769063.001.0001 Saving for Democracy Thrift, Sacrifice, and the World War II Bond Campaigns Kiku Adatto DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199769063.003.0016 Abstract and Keywords This chapter recounts the war bond campaign of the Second World War, illustrating a notion of thrift fully embedded in a social attempt to serve the greater good. Saving money was equated directly with service to the nation and was pitched as a duty of sacrifice to support the war effort. One of the central characteristics of this campaign was that it enabled everyone down to newspaper boys to participate in a society-wide thrift movement. As such, the World War II war bond effort put thrift in the service of democracy, both in the sense that it directly supported the war being fought for democratic ideals and in the sense that it allowed the participation of all sectors in the American war effort. This national ethic of collective thrift for the greater good largely died in the prosperity that followed World War II, and it has not been restored even during subsequent wars in the latter part of the 20th century. Keywords: Second World War, war bonds, thrift, democracy, war effort Page 1 of 56 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). -

Charlie Chaplin's

Goodwins, F and James, D and Kamin, D (2017) Charlie Chaplin’s Red Letter Days: At Work with the Comic Genius. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 1442278099 Downloaded from: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/618556/ Version: Submitted Version Publisher: Rowman & Littlefield Please cite the published version https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk Charlie Chaplin’s Red Letter Days At Work with the Comic Genius By Fred Goodwins Edited by Dr. David James Annotated by Dan Kamin Table of Contents Introduction: Red Letter Days 1. Charlie’s “Last” Film 2. Charlie has to “Flit” from his Studio 3. Charlie Chaplin Sends His Famous Moustache to the Red Letter 4. Charlie Chaplin’s ‘Lost Sheep’ 5. How Charlie Chaplin Got His £300 a Week Salary 6. A Straw Hat and a Puff of Wind 7. A bombshell that put Charlie Chaplin ‘on his back’ 8. When Charlie Chaplin Cried Like a Kid 9. Excitement Runs High When Charlie Chaplin “Comes Home.” 10. Charlie “On the Job” Again 11. Rehearsing for “The Floor-Walker” 12. Charlie Chaplin Talks of Other Days 13. Celebrating Charlie Chaplin’s Birthday 14. Charlie’s Wireless Message to Edna 15. Charlie Poses for “The Fireman.” 16. Charlie Chaplin’s Love for His Mother 17. Chaplin’s Success in “The Floorwalker” 18. A Chaplin Rehearsal Isn’t All Fun 19. Billy Helps to Entertain the Ladies 20. “Do I Look Worried?” 21. Playing the Part of Half a Cow! 22. “Twelve O’clock”—Charlie’s One-Man Show 23. “Speak Out Your Parts,” Says Charlie 24. Charlie’s Doings Up to Date 25. -

Official Report-1944

OFFICIAL REPORT-1944 THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF SCHOOL ADMINISTRATORS A Department of the X.nJoml Education As.sociation of the United St;ucs 57^,. WARTIME CONFERENCES ON EDUCATION r H E M E /fvy Tk Pt'oplc'5 Scliools m War awA Peace Seattle • Atlanta • Islew York • Chicago • Kansas City UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARIES EDUCATION LIBRARY OFFICIAL REPORT Wartime Conferences on Education STATE ri^T ;Vf '• ^^ "^^ AND «-**—— ••*- >»Aii>i£SV|iajB, ^^j^ FLA. SEATTLE January 10-12, 1944 ATLANTA February 15-17, 1944 NEW YORK February 22-24, 1944 CHICAGO February 18-March 1, 1944 KANSAS CITY March 8-10, 1944 THE.AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF SCHOOL ADMINISTRATORS A Department of the National Fducation Association of the United States 1201 SIXTEENTH STREET, NORTHWEST, WASHINGTON 6, D. C. March 1944 PRICE, $1 PER COPY : J 7^. Cr rDOCATIOS LfBBlil N FEBRUARY 1940, the railroad yards at St. Louis were filled with the special trains and extra Pullmans handling the convention travel of the American Associa- tion of School Administrators. Special trains and extra Pullmans for civilians were early war casualties. In February 1941, two hundred and eighty-two firms and organi- zations participated in the convention exhibit of the American Association of School Administrators in the Atlantic City Audi- torium. Today, the armed forces are occupying that entire audito- rium, one of the largest in the world. In February 1942, the official count showed that 12,174 persons registered at the San Francisco convention. The housing bureau assigned 4837 hotel sleeping rooms. *Now every night in San Francisco, long lines of people stand in hotel lobbies anxiously seeking a place to sleep. -

An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films Heidi Tilney Kramer University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2013 Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films Heidi Tilney Kramer University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kramer, Heidi Tilney, "Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4525 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films by Heidi Tilney Kramer A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Women’s and Gender Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Elizabeth Bell, Ph.D. David Payne, Ph. D. Kim Golombisky, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 26, 2013 Keywords: children, animation, violence, nationalism, militarism Copyright © 2013, Heidi Tilney Kramer TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................................................ii Chapter One: Monsters Under -

Crossroads Film and Television Program List

Crossroads Film and Television Program List This resource list will help expand your programmatic options for the Crossroads exhibition. Work with your local library, schools, and daycare centers to introduce age-appropriate books that focus on themes featured in the exhibition. Help libraries and bookstores to host book clubs, discussion programs or other learning opportunities, or develop a display with books on the subject. This list is not exhaustive or even all encompassing – it will simply get you started. Rural themes appeared in feature-length films from the beginning of silent movies. The subject matter appealed to audiences, many of whom had relatives or direct experience with life in rural America. Historian Hal Barron explores rural melodrama in “Rural America on the Silent Screen,” Agricultural History 80 (Fall 2006), pp. 383-410. Over the decades, film and television series dramatized, romanticized, sensationalized, and even trivialized rural life, landscapes and experiences. Audiences remained loyal, tuning in to series syndicated on non-network channels. Rural themes still appear in films and series, and treatments of the subject matter range from realistic to sensational. FEATURE LENGTH FILMS The following films are listed alphabetically and by Crossroads exhibit theme. Each film can be a basis for discussions of topics relevant to your state or community. Selected films are those that critics found compelling and that remain accessible. Identity Bridges of Madison County (1995) In rural Iowa in 1965, Italian war-bride Francesca Johnson begins to question her future when National Geographic photographer Robert Kincaid pulls into her farm while her husband and children are away at the state fair, asking for directions to Roseman Bridge. -

An Analysis of American Propaganda in World War II and the Vietnam War Connor Foley

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Honors Program Theses and Projects Undergraduate Honors Program 5-12-2015 An Analysis of American Propaganda in World War II and the Vietnam War Connor Foley Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/honors_proj Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Foley, Connor. (2015). An Analysis of American Propaganda in World War II and the Vietnam War. In BSU Honors Program Theses and Projects. Item 90. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/honors_proj/90 Copyright © 2015 Connor Foley This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. An Analysis of American Propaganda in World War II and the Vietnam War Connor Foley Submitted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for Commonwealth Honors in History Bridgewater State University May 12, 2015 Dr. Paul Rubinson, Thesis Director Dr. Leonid Heretz, Committee Member Dr. Thomas Nester, Committee Member Foley 1 Introduction The history of the United States is riddled with military engagements and warfare. From the inception of this country to the present day, the world knows the United States as a militaristic power. The 20th century was a particularly tumultuous time in which the United States participated in many military conflicts including World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Persian Gulf War, and several other smaller or unofficial engagements. The use of propaganda acts as a common thread that ties all these military actions together. Countries rely on propaganda during wartime for a variety of reasons. -

World War II Posters West Texas a & M University

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato Art and Music Government Documents Display Clearinghouse 2007 Art of War: World War II Posters West Texas A & M University Follow this and additional works at: http://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/lib-services-govdoc-display- art Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the Collection Development and Management Commons Recommended Citation West Texas A & M University, "Art of War: World War II Posters" (2007). Art and Music. Book 3. http://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/lib-services-govdoc-display-art/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Government Documents Display Clearinghouse at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Music by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Art of War Sources A 1.35:231 Blackout of Poultry Houses and Dairy Barns A 1.59:7 Take Care of Household Rubber A 1.59:30 Victory Garden: Leader's Handbook A 1.59:54 Green Vegetables in Wartime Meals Victory Gardeners can Prevent Ear-worms from Entering A 1.59:58 Their Corn Produce More Meat, Milk and Leather with No More Feed by A 1.59:72 Controlling Cattle Grubs A 1.59:95 Victory Garden Insect Guide A 1.59:103 Pickle and Relish Recipes A 13.20/3:F Protect His America! Only You can Prevent Forest Fires 51/54 [poster] -

World War II Information Collection, 1942-1951

WORLD WAR II INFORMATION COLLECTION A Register, 1942-1951 Overview of Collection Repository: Clemson University Libraries Special Collections, Clemson, SC Creator: War Information Center (Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina) Collection Number: Mss 253 Title: World War II Information Collection, 1942-1951 Abstract: The War Information Center was established at Clemson College in April 1942. It was one of roughly 140 colleges and universities across the United States designated by the Library Service Division of the U.S. Office of Education to receive a wide range of publications and information in order to keep communities informed about the war effort in an age before mass media. The collection contains materials that document the events of World War II and its immediate aftermath. Quantity: 24 cubic feet consisting of 93 folders in 6 letter-sized boxes / 84 oversized folders / 10 oversized boxes. Scope and Content Note The collection includes publications, brochures, newsletters, news-clippings, posters, maps, ration coupons, and Newsmaps detailing the events of World War II. The collection dates from 1942-1951. The bulk of the material dates from the U.S. war years of 1942-1945. The subject files date from 1942-1945 with one correspondence file dated 1951. The World War II posters date from 1942-1946. The war-related maps date from 1941-1945. The Newsmaps date from 1942-1948. The subject files are arranged in alphabetical order by folder title. The news-clippings are arranged in chronological order. The oversized World War II posters, maps, and Newsmaps have detailed separation lists provided. The subject files contain pamphlets, newsletters, publications, brochures, and articles that document the activities of countries that fell to German occupation. -

Exe Pages DP/Mtanglais 25/04/03 15:59 Page 1

exe_pages DP/MTanglais 25/04/03 15:59 Page 1 SELECTION OFFICIELLE • FESTIVAL DE CANNES 2003 • CLÔTURE MARIN KARMITZ présente / presents Un film de / a film by CHARLES CHAPLIN USA / 1936 / 87 mn / 1.33/ mono / Visa : 16.028 DISTRIBUTION MK2 55, rue traversière 75012 Paris Tél : 33 (0)1 44 67 30 80 / Fax : 33 (0)1 43 44 20 18 PRESSE MONICA DONATI Tél : 33 (0)1 43 07 55 22 / Fax: 33 (0)1 43 07 17 97 / Mob: 33 (0)6 85 52 72 97 e-mail: [email protected] VENTES INTERNATIONALES MK2 55, rue traversière 75012 Paris Tél : 33 (0)1 43 07 55 22 / Fax: 33 (0)1 43 07 17 97 AU FESTIVAL DE CANNES RÉSIDENCE DU GRAND HOTEL 47, BD DE LA CROISETTE 06400 CANNES Tél : 33 (0)4 93 38 48 95 SORTIE FRANCE LE 04 JUIN 2003 EN DVD LE 12 JUIN 2003 exe_pages DP/MTanglais 25/04/03 15:59 Page 2 Synopsis The Tramp works on the production line in a gigantic factory. Day after day, he tightens screws. He is very soon alienated by the working conditions and finds himself first in the hospital, then in prison. Once outside, he becomes friends with a runaway orphan girl who the police are searching for. The tramp and the girl join forces to face life's hardships together... exe_pages DP/MTanglais 25/04/03 15:59 Page 4 1931 - Chaplin leaves Hollywood for an 18-month tour of the world. He The Historical Context meets Gandhi and Einstein, and travels widely in Europe.